Steve McQueen trained as a painter before turning to video art. His early films were silent, monochrome, focusing on his own body because it was cheaper than hiring an actor. Many of the works in his retrospective at Tate Modern (which won’t reopen when the museum does later this month because it doesn’t meet ‘museum regulations for social distancing in enclosed spaces’) are shot with the camera held so close that at times you couldn’t slide a cigarette paper between McQueen’s lens and his subject. For Girls, Tricky (2001), he squeezed into a tiny booth in a recording studio with the musician Tricky. The cameraman is quickly forgotten. Apart from the occasional flash of gold teeth, Tricky is in permanent shadow, eyes closed as he sings (though it’s more incantation than song): ‘Girls wish you never had boys/They grow up to be bad boys/Cry I’ve never had boys/Never seen your dad boy/I’ve never seen my dad boy.’

Illuminer (2001), shot in a dark hotel room, is a kind of companion piece to Girls, Tricky. We can just about make out the shape of a man (the catalogue tells us it’s McQueen himself). He lounges, bored, on the bed, half-watching a French TV news report of what sounds like a battle (in fact it’s a US military exercise in Afghanistan). Occasional bursts of gunfire break the silence in the room. We can’t see the TV, because McQueen has placed the camera (an everyday digital camera) on top of the monitor. Instead we see the rough shadows it casts across the room as the camera tries to adjust to the changing light levels. The only fixed point is a small circle of light from the man’s watch. Illuminer was shot spontaneously – McQueen doesn’t adhere to any grand theory of filmmaking – but it’s more than an experiment in the limits of vision. The eerie blue and purple light is reminiscent of documentaries in which nocturnal animals are captured by infrared cameras. McQueen’s default to darkness in many of these pieces is disorientating. His subjects are in danger, or we are. What’s really going on proves elusive.

A reckoning with slavery is often a rite of passage for artists and writers of the African diaspora. McQueen denies that this applies to him, but his work, particularly Twelve Years a Slave, suggests otherwise. Like much of the Caribbean, Grenada (his father’s birthplace) was forged in the violence generated by the arrival of Europeans. Caribs’ Leap (2002) refers to the Carib Indians who resisted colonisation by the French in 1651 by leaping off cliffs to their deaths. In the film, shown on a monitor positioned twenty feet up in the gallery, white clouds billow across a small screen. For a long time nothing appears to happen, then, almost imperceptibly, a man in free fall comes into view, seeming to float rather than fall. The camera tracks him – arms flapping, legs kicking out – as he crosses the sky. But he doesn’t descend; neither the world nor any man holds dominion over him. There is no desperation or finality in his movement. It’s an affirmation of freedom – a lover’s leap and an act of faith.

The ethereality of Caribs’ Leap is countered by the underworld of Western Deep (2002), which casts the viewer into TauTona, the world’s deepest gold mine, on the outskirts of Johannesburg. McQueen ‘wanted something that the viewer could hold onto, that had texture, the texture of the rock, the drilling and mining … I wanted the audience to feel the molecules of dust.’ The texture comes from the graininess of the film, which is partly a result of the transfer from Super 8 film to video. In his movies, including Hunger and Twelve Years a Slave, McQueen shows a fascination with extreme experiences, with what the body can endure. In Western Deep, the camera, standing in for the viewer, snakes along the labyrinthine shafts and tunnels, tracking the miners’ descent. At its deepest, more than two miles down, temperatures soar to 80°C, and the camera captures its impact by proxy: after their shift, the men are taken to a medical facility where thermometers are placed in their mouths; their brows drip with sweat, their glazed eyes are exhausted and febrile.

The intensity of working underground has been documented before, of course. Perhaps the earliest example is Alberto Cavalcanti’s Coal Face, made for the GPO film unit in 1935, with a script by W.H. Auden and a score by Benjamin Britten. The film, Cavalcanti said, was ‘an experiment in sound’. Western Deep has a similarly unpredictable soundtrack, shifting abruptly from deafening loudness to silence. The miners at TauTona, however, are accorded far less humanity than the miners of Coal Face. They’re forced to complete drills which have nothing to do with their work – jumping on and off a block, for instance, in time with a blaring horn and flashing red light. These accelerating repetitive actions appear to be nothing more than a pointless exercise, a gratuitous punishment. But if the men are reduced, as McQueen implies, to units of labour, they are also the involuntary constituents of his art. The film has no narrator, inviting the viewer’s own, perhaps unflattering, interpretation.

There’s less room for ambiguity in End Credits (2012-16), for which McQueen filmed thousands of pages of FBI files, largely redacted, on Paul Robeson. The files pass across the screen as if on microfiche, overlaid by the voices of actors reading the transcripts. The 13 hours of footage and 19 hours of audio quickly get out of sync; the files flash past, abstracted, while the word ‘redacted’ becomes a sort of mantra. What, in the end, did the authorities know about Robeson after decades of surveillance? It’s impossible to tell because so much is redacted. The most compelling piece in the show, 7th Nov. (2001), is a huge, floor-to-ceiling colour photograph of a man lying on a mortuary table (the scar on his skull suggests an autopsy). In the accompanying recording, McQueen’s cousin recounts a catastrophic accident that resulted in the death of his brother. It’s told in a halting manner: the two men were messing around with a handgun when it unexpectedly discharged. The surviving brother had his finger on the trigger.

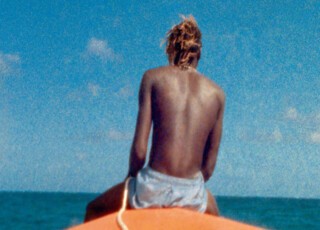

McQueen’s work returns again and again to the question of how to mark a life, particularly one ended by violence. In Grenada in 2002, he filmed a young fisherman called Ashes riding the prow of his boat. Not long afterwards, Ashes discovered – and seized – a cache of drugs on a deserted beach. The gang members tracked him down and shot him dead. When McQueen learned of the murder on returning to Grenada years later, he arranged for the construction of a memorial. The film he made in response bisects the gallery space. On one wall we see footage of men at work in the cemetery; the other wall glows blue with the light of the film projected on the reverse: Ashes, astride a small fishing boat, bobbing up and down in the sea.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.