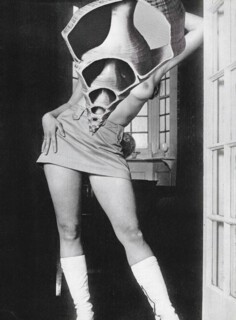

On 5 November 1982, the post-punk group Ludus played a gig at the Haçienda, the Manchester club run by Factory Records and best known today for its association with New Order and the Happy Mondays. Ludus were a more exotic proposition: jazz-schooled, scratchy and fronted by Linder, a visual artist whose songs channelled her decade-long engagement with second-wave feminism, as well as her anti-consumerist, vegetarian politics. In the blurry footage of the Haçienda gig on display at Linderism, a retrospective at Kettle’s Yard (until 31 August, currently closed), you could only vaguely make out the ‘meat dress’ she fashioned out of discarded chicken parts. But it was hard to miss what came next. Halfway through ‘Too Hot to Handle’ – ‘I ask for bread and you give me stones; I need a dress to cover my bones’ – Linder tore off her skirt to reveal a shiny black dildo. The audience of angular indie boys, she says, drew back from the stage, aghast.

Linder was born Linda Mulvey in 1954. She discovered The Female Eunuch and Spare Rib around the same time she fell for the retro-futurist allure of Roxy Music; in the early 1970s her outfit of choice was a WAAF uniform and red stilettos. An intellectual, art-glamour side to the Manchester punk scene emerged after everyone, Linder included, went to see the Sex Pistols at the Lesser Free Trade Hall in June 1976. Her early designs for friends’ record sleeves featured floating Expressionist heads (Real Life by Magazine) and photomontages inspired by Dada and Surrealism (the Buzzcocks’ ‘Orgasm Addict’). When she formed her own group, her persona was as much indebted to female artists of the era – Hannah Wilke, Carolee Schneemann, Lynda Benglis – as it was to the usual punk exemplars. An early photographic series shows drag artists at Manchester’s gay club Dickens; in one, a short man in tux and blonde bouffant looks warily up at the majestic performer Lana Pellay. Linder was always interested in states of heroic androgyny.

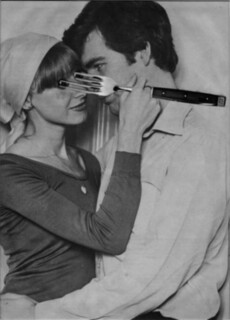

She remains best known for her photomontages, executed then as now with a Swann-Morton No. 11 surgical scalpel (‘ideal for stab incisions’, according to the manufacturer’s website). She had already begun cutting and collaging pictures from magazines – Family Circle, True Confessions – and from her mother’s G Plan catalogue when, in 1976, she saved up to buy Dawn Ades’s Thames and Hudson volume Photomontage, which exposed a new generation to the interwar art of John Heartfield, George Grosz and Hannah Höch. The earliest of Linder’s collages have a graphic simplicity borrowed from fashion illustration, sometimes with a twisted take on ageing glam rock: one of the mocked-up female faces looks like Brian Connolly, the lead singer of the Sweet. Linder initially drew or painted over found images: on a page from a Damart catalogue, for instance, she gave thermal underwear models garish lingerie and scurrilous genitalia. Guided by Ades’s book, she turned exclusively to montage. Her punk-era images are furious and precisely focused. Images from pornography, hard and soft, collide with mid-1970s interiors and consumer goods. The full-colour montage used for the Buzzcocks cover shows a gleaming naked model with an electric iron where her head should be and toothy lipstick smiles in place of nipples. On a red-brown sofa, a monochrome man and woman with television-set faces engage in flagrant foreplay, but their crotches have been obscured by a TV remote and a vacuum cleaner. Elsewhere things are subtler: Linder’s minimally modified photographs of straight couples are often the most unnerving and the funniest. A boy and girl embrace; as she looks over his shoulder, she stabs her own eyes with a dinner fork. In some cases, the montage consists in the smallest disturbing addition: under the caption ‘Out of the Blue’, a girl lays her hand on a young man’s shoulder and looks at the camera with mismatched eyes that are not her own. There is an echo here of Dora Maar’s The Pretender (1936), which shows a contorted child with adjusted eyes, madly staring.

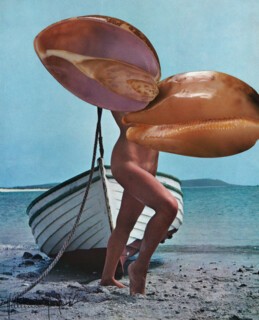

Much of Linder’s early work languished unseen until, around 2006, she took up montage again and began to exhibit her archive. Pornography remains an important source, though it’s harder today to find suitable print magazines, and she has begun to treat these images as a kind of aesthetic backdrop for new subjects. In the recent work at Kettle’s Yard, flowers explode from bodies and faces, with garish or dusky roses cut from old colour catalogues. (The postwar heyday of the rose catalogue, Linder says, ended in the 1970s.) The monstrous forms in these pictures bring Linder a little closer to the other great British monteur of her era, John Stezaker, who spliced film stills and landscapes to produce nightmarish images. In Linder’s work, florid sea shells obscure the faces of vintage pin-ups, and abstract streaks of enamel paint attack dancers in images taken from a 1938 book about the Ballets Russes. When they were first shown these works seemed like a glamorous return to her work of the 1970s; but when you look at them again now these dancers are among her strangest and most seductive work. They seem to exist out of time, in the dream space of photomontage opened up by Maar and Höch almost a century ago.

At Kettle’s Yard, a vitrine displayed books that have provided Linder with source material – Miniature Roses: Their Care and Cultivation, The Art and Craft of Hairdressing, Baron at the Ballet (a selection by the society photographer) – and a bristling array of other ephemera: Linder’s felt-tip notes on German photomontage; scraps of layout from The Secret Public, the magazine she made with the writer Jon Savage; photographs of Howard Devoto, the frontman of Magazine, wearing fetish masks made from lingerie; a page from the Ludus accounts for spring 1979 (‘Excess expenditure over income: £102.84’). Nearby, the Haçienda footage played on a big screen, looped in slow motion with an alternative soundtrack by Linder’s son, Maxwell, transforming a notorious incident into a stately ceremony, closer to the kind of mantic performance art that has occupied Linder in recent years. There were traces of that ritual practice, and further instances of Linder’s photomontage, on display in the Kettle’s Yard house itself, inserted among the modest domestic objects and elegant 20th-century artworks (Moore, Hepworth, Brâncuși, Gaudier-Brzeska). Linder’s slashed images and ritualistic artefacts looked surprisingly happy here. My favourite: a pair of vintage Joseph LaRose heels sprouting manes of blonde hair, a homage to St Liberata, one of several female Christian saints reputed to have sprouted beards when the exclusivity of her devotion to Christ was threatened by men.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.