‘Anew type has emerged,’ a critic wrote after the raucous premiere of Alfred Jarry’s Ubu roi in Paris in December 1896, ‘a popular legend of base instincts, rapacious and violent.’ ‘What more is possible?’ W.B. Yeats, who was in attendance, recalled in his autobiography. ‘After us the Savage God.’ Was the uproarious Ubu an early intimation of his ‘rough beast’ slouching towards Bethlehem? Ubu roi is also a Second Coming of sorts, and certainly ‘mere anarchy is loosed upon the world’ in it. But where Yeats is grand, Jarry goes lower than low, and where Yeats has his heraldic falcon spin a ‘widening gyre’ high in the sky, the obscene Ubu wears his intestinal spiral on his enormous belly.

Jarry based his play on an old skit called Les Polonais which he cooked up with fellow students at his lycée in Rennes to mock a hapless physics instructor called M. Hébert, aka Père Hébé. With touches drawn from Rabelais, Guignol and Nietzsche, Jarry extended this adolescent attack on one teacher into a broad satire on all authority. Ubu roi is, essentially, a parody of Macbeth with allusions to Falstaff and Napoleon thrown in. Père Ubu opens the play with a notorious ‘Merdre!’, the extra ‘r’ putting his stamp on a crappy world. Immediately Mère Ubu, his wife, urges her ‘dirty old man’, who has somehow become aide-de-camp to King Wenceslas of Poland, to seize the crown. Unlike Macbeth, Ubu needs no convincing, because he has no conscience: in Ubu cocu (‘cuckolded’), a sequel to the play, he even flushes a character named Conscience down the toilet. This Super-Id – Jarry once described Ubu as ‘the ignoble otherself’ – not only kills the king but dispatches the Polish aristocracy, peasantry and judiciary too. ‘Who will administer justice now?’ Mère Ubu asks. ‘Why, I will,’ Ubu responds in one line among many that seem torn from the pages of the Trumpian present. ‘You’ll see how well things will go.’ The Ubus first loot Poland of its gold, then set its army against the tsar; their ultimate aim is to ‘butcher the world’. Finally pushed back by the Russians, they escape to France, where Ubu plans to become ‘Master of Phynances’. ‘Phynances’ is Jarryese for royalties that popular writing receives but never deserves.

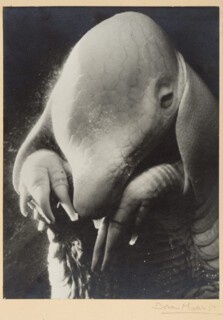

Born in 1873, Jarry was a rebel but not an outsider. A brilliant student at the famed Lycée Henri-IV in Paris, he accidentally on purpose failed the test three times for the École Normale Supérieure. This freed him to hang out in the Symbolist circle around the Mercure de France gazette, where he became friendly with Mallarmé, Remy de Gourmont and Marcel Schwob, writing hermetic poems and obscure notes on theatre. He also came to know some wayward artists, such as Gauguin, whom he visited in Brittany; Bonnard, Sérusier, Toulouse-Lautrec and Vuillard all chipped in with masks and sets for Ubu roi. Although the play was performed only twice at the tiny Théâtre de l’Œuvre, it made Jarry famous overnight. Straightaway he identified with his character, taking on his idiom and manner. ‘A nutcracker, if it could talk,’ Gide commented, ‘would do no differently.’ Nevertheless, the likes of Apollinaire, Picasso, André Salmon and Max Jacob were drawn to Jarry, who lived fast, died young and left an unbeautiful corpse, more or less suicided by poverty and drink at 34 (the autopsy indicated tuberculous meningitis, but it was absinthe that did him in). This grim end only added to his posthumous allure. The Dadaists claimed him as a precedent, as did the Surrealists; Hans Arp read Ubu roi at the Cabaret Voltaire in Zurich; Ernst, Miró and Dora Maar made images based on Ubu: Jarry has left what Greil Marcus calls ‘lipstick traces’ to this day. Since 1978, Dave Thomas has kept his spirit alive with the band Père Ubu – punks owe a lot to Jarry – and William Kentridge used his creature to comment on the barbarisms of apartheid. A small but suggestive show at the Morgan Library in New York (until 10 May), smartly curated by Sheelagh Bevan with well-chosen publications, prints and photos mostly from the recently donated Stillman Collection, examines his short life and long afterlife, along with his explosive writing.

How do the Symbolist Jarry and the Ubu Jarry fit together? Roger Shattuck, whose classic book on the Belle Époque, The Banquet Years (1955), first turned me on to Jarry, sees ‘the personal lyric’ and ‘the horrendous farce’ as two sides of a ‘sustained hallucination’. A vision of destruction followed by a project of reconstruction became common in the early 20th-century avant-garde. After Expressionism and Cubism in the 1910s came the Retour à l’ordre in the 1920s, and in the wake of the First World War many artists and writers, not to mention politicians, swung hard from left to right. Yet Jarry lived the extremes of disruption and order at the same time. Although he was close to anarchist circles, he wasn’t strictly an anarchist himself, and just two years after Ubu roi he wrote Gestes et opinions du docteur Faustroll, pataphysicien, which Shattuck describes as ‘a stupendous effort to create out of the ruins Ubu had left behind a new system of values – the world of Pataphysics’. ‘Pataphysics lies as far beyond metaphysics as metaphysics lies beyond physics,’ Jarry semi-explains, ‘in one direction or another.’ That last bit keeps open the option that it’s a joke, or at least a tease – and just as Ubu mocks Macbeth, so Faustroll trolls Faust. Nevertheless, as ‘the science of imaginary solutions’, pataphysics is also meant to assist with a life riven by contradiction. Certainly the College of Pataphysics attracted artists and writers dedicated to paradox: Duchamp, Ionesco, Leiris, Dubuffet, Queneau.

Yet if Jarry has lived on it is because of Ubu above all. Ubu was a ‘self-inflicted nightmare’, Jarry admitted, but the romance of self-destruction also enticed him. Although he wasn’t the first to be so seduced – Baudelaire and Rimbaud precede him – he was flagrant about it, and many have fallen for his version of the avant-gardist in extremis since. One immediate legatee was Hugo Ball, the first ringleader of Zurich Dada, which Ball described as at once ‘a buffoonery and a requiem mass’. ‘Everyone has become mediumistic,’ he wrote in Flight out of Time, his great diary of his Dada years, ‘from fear, from terror, from agony, or because there are no laws anymore – who knows?’ Ball endorsed a tactic of ‘mimetic exaggeration’, defining the Dadaist as one who embodies the ‘dissonances’ of the age ‘to the point of self-disintegration’. But what Jarry proposed was different: he called it ‘inverse mimicry’. Rather than adapt to the environment in order to survive – his example is a butterfly that, ‘in order not to be recognised as a butterfly, imitates a dead leaf’ – why not imagine a creature that thrives by forcing the world to adapt to it? ‘In some strange way their exuberant personalities exude their own special surroundings which could not possibly have any existence at all without them,’ Jarry commented about the characters of the Symbolist Henri de Régnier. ‘They congeal their surroundings into their own image and erect palaces of space around themselves … The author has turned his creatures inside out and exposed their soul: the soul is a nervous tic.’ Surely Jarry also had Ubu in mind here: the king who sees his image everywhere and gaslights like mad. (‘It’s a manifest imposture,’ a character in Ubu cocu protests. ‘A magnificent posture!’ Ubu retorts.) He has plenty of courtiers and underlings – Jarry uses the word palotins, nicely translated into English as ‘Palcontents’ – who are ‘perfect for anyone who wishes his Will to be sovereign law’. Jarry even imagines Ubu with a ‘Disembraining Machine’, a ‘democratic spectacle’ better than any royal guillotine or anarchist bomb, and can only rue that ‘this Golden Age is far in the future.’

The connection to Trump is obvious enough, and it isn’t just a matter of his Ubuesque girth. Ubu is a travesty of sovereignty, styled as he was after the Daumier caricatures of the rotund King Louis-Philippe as a poire, close enough to père. Ubu is both father and baby, both sovereign and beast; he represents the authoritarian leader as monster infant (the innocent child of Wordsworth is long gone, the Ferdydurke world of Gombrowicz is on the horizon). In the psychoanalytic scheme of things Ubu is also akin to the ‘primal father’, the almighty patriarch who is shame-free to boot. Soon after the end of the First World War, Freud sensed that mass politics had revived this ‘dangerous personality towards whom only a passive-masochistic attitude is possible’: ‘the group still wishes to be governed by unrestricted force; it has an extreme passion for authority.’ Why? Because the primal father both embodies the law and transgresses it, and this opens up a powerful double identification for his followers: they submit to the leader as authority and envy him as outlaw. Trump is one part Père Ubu, one part primal father; so are Duterte, Bolsonaro, Putin, Boris Johnson …

‘Living is the carnival of being,’ Jarry liked to say. Although this has a pataphysical meaning – essentially, that living is better when undisturbed by thinking – we can understand carnival here in the Rabelaisian sense as a temporary reversal of the given hierarchy: bottom goes on top, top goes bottom, refreshing the social order. But what if that reversal gets stuck and the clown stays king – or, rather, what if the two positions are collapsed into one? What happens when a travesty of authority becomes a template for power, when Dada sets up in the White House or at 10 Downing Street? What is the left to do when the right appropriates its cultural-political strategies? How are artists and writers who have long assumed a monopoly on transgression to respond? It might be time to put strategies of ‘mimetic exaggeration’ and ‘inverse mimicry’ aside for a while.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.