The excellent exhibition Last Supper at Pompeii at the Ashmolean (until 12 January) is about much more than what Pompeians had for dinner. A fresco that once decorated the lararium (the shrine of the household gods) of a large Pompeian villa illustrates food production in the Bay of Naples. Bacchus, elaborately dressed as a bunch of grapes, is shown standing in front of a mountain – almost certainly Vesuvius – the lower slopes of which are covered with cultivated vines. By the first century CE, viticulture dominated agricultural output in the area. Based on calculations regarding the size and quantity of dolia (storage jars) excavated at ancient country villas, it’s estimated that Neapolitan vineyards were capable of producing more than a hundred million litres of wine a year, much of which was exported. Many Pompeians would have drunk local wine, grown in open spaces within the town as well as on the vast estates outside, but the painted label on one amphora indicates they also imported wine – in this case from Rhodes. Other amphorae brought wheat from North Africa and dates from Palestine.

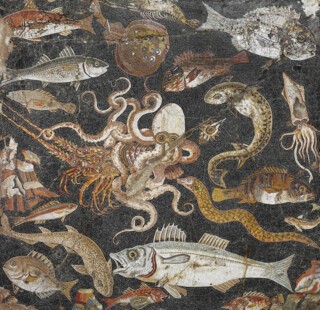

The fertile volcanic soil of the Bay of Naples is one reason for Pompeii’s rich food culture; the other is the sea. Numerous fish bones and urchin and mussel shells have been recovered from Pompeii’s drains and latrines. A brilliant mosaic, once the centrepiece of a floor in the House of the Faun, depicts 22 kinds of underwater creature, including red gurnard, golden mullet, and a duelling octopus and lobster. Another, more modest, mosaic features a bottle of garum, a salty paste made from fermented fish entrails. The bottle bears the name ‘Aulus Umbricius Scaurus’, a garum magnate thought to have been responsible for up to a third of production in the town – it is from his villa that the mosaic comes. This is no generic vessel but a celebration of Scaurus’ brand.

Eating out in Pompeii was often a necessity rather than a luxury: many inhabitants of ancient cities had no means of preparing or cooking food at home. Street-side bars ran up and down every major road in Pompeii. Although there is plenty of evidence of this sort of consumption – in contemporary writings and frescoes, as well as the ruins of Pompeii itself – the meals of the wealthy receive greater attention at the Ashmolean. Visitors to the show progress through a garden, atrium, dining room and kitchen; the dining room in particular contains a number of exceptional pieces. Along one wall is a fresco nearly three metres in height, from the House of the Golden Bracelet. The painting shows an imagined opening in the wall, looking out onto a garden of leafy trees and songbirds. The entire room was intended to imitate an outdoor pavilion, providing diners in the centre of town with the fantasy of rus in urbe.

On display opposite the fresco is the Moregine hoard, a twenty-piece silver dinner service discovered in 1999 just outside the walls of Pompeii, comprising an assortment of cups, plates, stands and a spoon. A number of these items have been etched with more than one name, suggesting they passed through several owners. The terracotta tableware on display originated not only in Italy, but also Tunisia, Turkey and southern France. In the kitchen are storage and preparation vessels, a pie mould in the shape of a chicken, a glirarium jar for raising dormice and a cochlearium for keeping snails. Alongside this is a display of blackened fruit, nuts, legumes and cereal crops, carbonised by the heat of the fire but still discernible.

The exhibition moves from the kitchens of Italy to Roman Britain. Eating habits in Iron Age Britain had already begun to change before Claudius’ conquest in 43 CE. Legionaries from Italy and auxiliary soldiers from other provinces brought with them new foods: we can trace the arrival of figs, grapes, mulberries, coriander, celery, dill and lentil seeds. The interconnected empire is again underscored by amphorae. Two examples, both found in London, once contained tuna from Cadiz and garum from Antibes (there is also a wine barrel from Marseilles and Indian peppercorns).

Cereal crops were the main agriculture produce in Britain and fed a flourishing brewing industry. The widespread consumption of beer in the northern provinces of the Roman Empire is recorded on the Bloomberg tablets, the earliest written documents from Roman Britain, which were discovered in the mud of the River Walbrook in 2010, during the construction of Bloomberg’s headquarters in the City of London. One gives the wholesale costs of different beers, another addresses a barrel-maker, and a third names ‘Tertius’, a brewer, who is also mentioned in a tablet from Carlisle, where it seems he also had dealings. That the exhibition includes a significant display of Romano-British material isn’t obvious from its title. The pieces provide a comparison to life in the ancient Mediterranean and are also of significant interest in their own right.

Running concurrently at the Scuderie del Quirinale in Rome, the exhibition Pompeii and Santorini: Eternity in a Day (until 6 January) juxtaposes the disaster at Pompeii with the volcanic eruption on the Aegean island of Santorini (ancient Thera) 1700 years earlier. The ‘Minoan Eruption’ was so enormous that its tsunami hit Crete, seventy miles away, and blew Santorini into the three parts that exist today. In the 1960s, excavations at the site of Akrotiri uncovered an ancient town preserved beneath the debris. An array of earthenware vessels were found, decorated with painted geometric patterns, horses and dolphins. The frescoes, in particular, are remarkable both for their compositions and the brilliance of the pigments. On display at the Quirinale are scenes of youths returning from a fishing trip, extravagantly clothed female figures, and a river scene that shows real and fantastical animals running through palm trees.

The curators don’t attempt a direct comparison of the two eruptions and objects from Santorini and Pompeii are for the most part separated. Rooms about the domus, garden and triclinium contain mosaics, jewellery and other outstanding objects – luxurious and mundane – that might be expected of an exhibition on Pompeii, but for which the only obvious unifying theme is the town itself.

Although plaster casts have been made from the voids left by decayed organic materials at Akrotiri – wooden furniture, for example – no human remains have been discovered. The inhabitants of the town seem to have fled elsewhere. But the exhibition does include a number of human casts from Pompeii (or rather, resin copies of the original plaster casts). Most are displayed in the final rooms, which explore the reception of Pompeii’s destruction by artists from the 18th to the 21st century. The casts of four bodies are shown alongside artworks directly or indirectly responding to them by Allan McCollum, Antony Gormley, Giuseppe Penone and Medardo Rosso. There is something uncomfortable about the curation here, which runs close to characterising the contorted limbs and faces of the deceased as curios or works of art in themselves.

The exhibition at the Ashmolean also includes the cast of a victim; although, unlike the majority, which were made of plaster, this one was cast using wax and resin, giving it a glistening, yellowish appearance. Placed in a darkened room behind a wall, there is nothing overtly inappropriate about the display; however, it isn’t obvious how the cast relates to the theme of food. (What’s more, this cast is in fact from the nearby villa of Oplontis.) But Pompeii is famous because of the way it was destroyed, and a morbid allure has surrounded the fate of its inhabitants since the site was rediscovered in the late 18th century. A show on the ancient site is expected to include something about death and destruction. The way in which such works should be displayed is always a challenge in exhibiting Pompeii.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.