Miners in the Snow (1880) was Vincent van Gogh’s first pictorial declaration of intent. Unable to hold down work in the family picture trade or as a preacher, he was persuaded by his brother Theo to turn his energies to drawing, and after some copying exercises he came up with this sheet. A large – roughly A2 – and scruffy affair, worked mostly in graphite with touches of wash and chalk, it is currently on show at the exhibition Van Gogh and Britain at Tate Britain (until 11 August). The intent was panoramic. Van Gogh shows the workforce of the Borinage, a Belgian coalfield, as a dark, heavy-stepping procession trudging towards the distant pit with its towering work sheds, chimneys and slagheap. Between the labourers and their daily destination a thorn hedge rises: its bare twigs are the high point of this gawky beginner’s attempt – frisky little scribbles, full of pleasure. The drawing, with the inclusion of that plant life, stands as a ragged prospectus for the remaining ten years of Van Gogh’s career. His mark-making would reliably quicken wherever vegetation grew, but the stems and spurts always responded to the weight of life as people experienced it. There was a modern human condition, burdensome and coal-dependent. Infusions of nature (and later, by extension, of colour) were the remedies it needed.

Van Gogh shook off his former ambition to preach when he started to make pictures – and yet, not wholly. The Tate’s well-conceived show traces his mind’s didactic habits. Like a sermon-writer he trusted to metaphors, the more familiar the better. The meek miners in the snow are treading the road of life: the comparison at Tate with a Victorian snow scene of pilgrims going to church, half-remembered by Van Gogh, underscores the point. Avenues and gateways were similarly packed with metaphorical significance, and we are shown how Van Gogh, painting scenes in rural Brabant and in the Paris suburbs, latched onto the symbolisms of predecessor artists to affirm his own sentiments about life. Van Gogh’s Chair (1888) derives from the metonym that Luke Fildes devised in 1870 when he represented the death of Charles Dickens by picturing his vacant armchair. Van Gogh’s taste for swingeing, all-confronting symbols would come to fruition in his solar discs and sunflowers. The exhibition demonstrates that while his handiwork may alter, Van Gogh’s will to perorate persists.

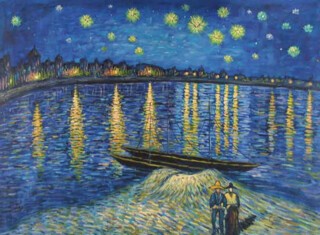

It persists, but only rarely after that first drawing is the scope of the homily panoramic. We are not shown the wild bid at cosmic allegory that is the Starry Night now held in New York; instead, we get an emphatically concrete Starry Night from the Musée d’Orsay, a chunky bas-relief in oil paint largely concerned with the gaslights of Arles and their reflections in the Rhône. Van Gogh better trusted his own efforts in the latter mode. It was only by attention to specifics – by staring at ‘a few clods of earth’, he told Emile Bernard, rather than by conjuring up ‘stars too big’ – that painters could lay hold on any sort of ‘modern reality’. And so we also have the Chair’s humbler successor, a low stone bench in the garden of the Saint-Rémy asylum painted from an easel placed not four feet away; the intensity with which Van Gogh has committed his gaze downwards draws us into his bow of submission. By contrast, a larger canvas painted in the same garden peers up at the sun-struck pines, soaring high beyond the surrounding buildings like flames against blue sky – a rush of ascension and release that remains observationally grounded. Elsewhere, closing in on the base of a yew trunk amid autumn evening fields, Van Gogh conjures up an image of mortality, of dark vigour leaching into wan earth.

The way in which Van Gogh was able to corral line and colour to elevate direct visual evidence during his final years remains astonishing. And yet the project that he had embarked on in 1880 relied quite as much on literature as on studying the work of other artists. Specifically – as Carol Jacobi, the exhibition’s curator, points out – Van Gogh leaned on English texts. Jacobi compares Miners in the Snow with the more accomplished write-ups of the same scenes that Vincent sent to Theo, and sees him overlaying on the Belgian black country the Coketown of Hard Times. Having passed much of his early twenties in England, Van Gogh was predisposed to regard the era in which he lived by reference to the novels of Dickens and Eliot. (It was only later that Zola would join his personal canon.) He took from the great Victorian novelists that his was an age that pushed individuals into small dark corners, insignificant socially but emotionally huge, and that to illuminate these local recesses was to begin the crucial task of compassion and consolation. English writers, moreover, were good at providing spiritual resources. Van Gogh had a particular fondness for Christina Rossetti, for Keats’s ‘To Autumn’ and for Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress. There was an interplay between metropolitan modernity and ‘noble and healthy sentiment’ that was peculiar to England, he suggested in letters to a Dutch friend: ‘It’s a different way of feeling, conceiving, expressing, which one has to get used to at first,’ yet to study it ‘more than repays the effort’.

Those letters were to a fellow beginner and showed off the more nuanced international sympathies that Van Gogh had gained during his years as a capital-hopping gallery hand for the art dealers Goupil and Cie. In the Netherlands, as through Europe generally, artists took their cue from Paris, with Jean-François Millet’s images of French peasants foremost in their sights. Millet had, in Van Gogh’s words, ‘reopened our thoughts to see the inhabitant of nature’. If contemporary painting from London was noticed at all, it was belittled as ‘literary’. But Van Gogh argued that in England texts and pictures were mutually invigorating, each helping to refine the audience’s sympathies. The draughtsmen of the Graphic, an illustrated London weekly, were to him the ‘deeper thinkers’ of the 1870s, carrying forward the social conscience of Dickens, while John Everett Millais, no less than his French homonym, possessed a manner affectingly and ‘personally intimate’.

In chasing the works that Van Gogh looked at in London, the Tate exhibition takes us on some journeys in taste. It is easy enough to be stirred by Millais’s Chill October, a lakeside landscape with a grip almost as plangent as those late Van Goghs, if conforming to a different etiquette. There is also the visual culture of ‘black and whites’: the lurid fantastical tinge lent to the metropolis by the visiting eye of Gustave Doré in London, his 1872 series of engravings, and the scenes of proletarian life by William Small and Frank Holl – the kind of work that Van Gogh was struggling to imitate around the time he turned thirty – that stand as formidable if unamiable exemplars of narrative force. I couldn’t achieve any liking for a prissily portentous symbolical six-footer by the now unfamiliar George Boughton, and yet Boughton mattered much to Van Gogh, and pioneered the composition to which Miners in the Snow was indebted. In similar fashion, Van Gogh would later fall in love with the intentions conveyed by Puvis de Chavannes in an allegorical frieze: in his approach to pictures, meaning would always remain primary.

A greater accommodation is required as you pass to the second part of the show. These later rooms explore the ways in which British artists returned the compliment after Van Gogh’s death and responded to his example. Francis Bacon’s three drunken fantasias of 1957, imagining Van Gogh as the plein air painter of 1888 stepping into the heat of Provence in existentialist defiance, deliver a giddy finale. En route, thanks to researches that have hunted down (too tenaciously, perhaps) every possible line of connection, we encounter succeeding generations of fans – those drawn to his work for formal reasons followed by devotees, such as Bacon, of his tragic biography. It makes for a confusing experience.

In his recent book Sensations, subtitled ‘The Story of British Art from Hogarth to Banksy’, Jonathan Jones reinterprets major artistic careers from the early 18th century until Turner’s death in 1851, at which point a daunting briar patch thwarts his progress.* As Jones sees it, art was ‘suffocated’ by the ‘tangle of Evangelical Christianity, moral scruple and high-mindedness’ that settled on Britain in the mid-19th century. And it was only after an entire century of ‘mediocrity’ that sleeping beauty rose to her feet (Bacon being Jones’s Prince Charming). Any visitor to the Tate exhibition can suggest something to alleviate Jones’s aesthetic headache (I would recommend the trenchant and uncompromisingly intelligent canvases of Harold Gilman), but collectively the artists assembled here hardly dispel his thesis. And yet when Jones opposes Victorian moralism to what he most admires in the British tradition – the observational empiricism that runs from Stubbs to Freud – this show surely contradicts him. Van Gogh has gained his unique status exactly because he combines the keenest observational practices with an evangelical cast of mind, a missionary intent to which his agonising life story bears witness. This makes him the channel through which the pieties that we associate with a past age have re-emerged and flourished. Loosed from its Christian and Romantic moorings, the thought that the created world might speak to us, as creatures in need of consolation, continues to communicate – thanks in no small part to Van Gogh.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.