There are self-trained artists; then there are self-willed ones. Edward Burne-Jones, like Vincent Van Gogh, was one of the latter. That’s to say, he decided, in 1855, to be an artist – he was studying for a theology degree at Oxford at the time – without knowing whether he was capable of being one, perhaps even without considering absence of talent a potential obstacle. Of course, he was talented. But that didn’t mean he didn’t have to work at it, even if he did have more beginner’s luck than Van Gogh, who, when he decided on his vocation aged 27, started off by reading a drawing manual nearly as old as he was. Burne-Jones, escaping to London, entered into a star-struck pseudo-apprenticeship under Dante Gabriel Rossetti, for whom, he later said, he would willingly have ‘been chopped up’. The oddness and severe limits of this artistic education, which Elizabeth Prettejohn emphasises in the catalogue accompanying the exhibition of Burne-Jones’s work at Tate Britain (until 24 February), is even more striking when you consider that Rossetti, despite having spent several years first at Sass’s Drawing School and then at the Royal Academy, was the most technically slipshod of the Pre-Raphaelites, regularly spurning the pained advice of his Brothers to do with perspective etc. He didn’t teach so much as let ‘poor Ned’ watch him at work (it was G.F. Watts, Burne-Jones recollected, who ‘much later … compelled me to try and draw better’). Thankfully, Burne-Jones also had William Morris, his friend from university. They had chosen the cause of art together, and Morris was to barrel their joint enterprise along for the next forty years or so.

Burne-Jones’s earliest works, done in the late 1850s, were in pen-and-ink, one of Rossetti’s specialities (‘I used to do it because I saw him do it’): they are dense, cramped compositions on medieval themes, the figures stylised, after the hand of the master. Later he experimented with watercolours (though they look more like oils – he mixed in gouache), which he began to exhibit. These too bear the heavy imprint of Rossetti. Looking back, Burne-Jones thought them ‘earnest passionate stammerings’: ‘There was such a passion to express in them and so little ability to do it.’ Indeed, they are often uncertain and marred by flaws of technique. But there are flashes of interest. A first outing in oils, an Annunciation triptych commissioned in 1860 for an altar in Brighton, glows sombrely, brown and black, with a spilling of gilt sky and reddish-gold haloes for the Holy Family (Mary is Jane Morris), so that you can forgive the way the third king’s feet stretch out like empty socks. Burne-Jones’s fascination with dangerous women bore fruit in the tiny but theatrical Sidonia von Bork (1860), which shows the sorceress brooding among tapestries, encased in a magnificent dress made up of what look like interlocking chains, and in the ambitious organisation of The Wine of Circe (1863-69), Circe’s back arched to meet the horizon of the sea beyond, as Odysseus’ ships hove into view. The climax was Phyllis and Demophoön (1870), a still-strange image of Phyllis emerging from the tree in which she has been imprisoned – don’t ask – and embracing her lost lover, who pivots away in alarm but can’t help turning to meet her gaze. This pose creates difficulties for the artist: there’s something off about the torsion of Demophoön’s upper body, not to mention the twist of his neck, and the furthest fingertip on his left hand is levitating out on its own. He’s also naked, without even the benefit of a fig leaf: his penis is a murky, puny thing, impossible to imagine anyone making a fuss over, but it was enough for the Old Watercolour Society to insist on its being veiled, which Burne-Jones refused to do. Instead, he resigned his membership, and hardly exhibited until the opening of the Grosvenor Gallery in 1877; the interval he described as the ‘seven blissfullest years of work that I ever had’.

The Burne-Jones who returned to storm the Grosvenor is recognisably the Burne-Jones we know. (Crudely: big paintings in oils, often very big, mainly of literary-medieval or mythological subjects, peopled by fey men and wan women in passive poses, eyes never quite meeting.) He had arrived at his mature style, fortified by two trips to Italy in 1871 and 1873, building on those of 1859 and 1862. Even in his lifetime, his friend George du Maurier was referring to the ‘Burne-Jonesiness of Burne-Jones’. This is the nub of the problem – to those who have one. His style is so tightly-wound, so cumbersomely itself, that the approaching viewer trips over the fact that they’re looking at a Burne-Jones before they can get anywhere near. He cannot surprise; his pictures don’t contain mysteries, besides, or in spite of, the ones they depict. This isn’t a new charge – even an admirer like Henry James thought Burne-Jones’s ‘languishing type … savours of monotony’ – but that hasn’t stopped reviewers of the Tate show serving up stale critique. Jonathan Jones of the Guardian called Burne-Jones ‘stupid’, while to Waldemar Januszczak of the Sunday Times – ‘send all his hopeless droopers to the gym’ – he is merely ‘ridiculous’. Tim Hilton made better reading in 1970, when he observed in his book on the Pre-Raphaelites that in Burne-Jones’s art ‘doing and dying … are hardly occurrences’, going on to say: ‘He does not paint to discover things, and this is why his art does not have a career.’

The contributors to the Tate’s catalogue naturally disagree, but the form of their defence is revealing of their anxieties. The Burne-Jones effect – of stillness, even lifelessness, stretched out over decades – is intentional, they argue, all part of his design – ‘design’ being the word. According to Prettejohn, Burne-Jones is best thought of as an intellectual, a designer rather than a painter. This is to push him more firmly out of Pre-Raphaelitism and into Aestheticism: away, that is, from narrative and lightly encoded meaning, as well as a fierce moral attention to the natural world, and towards beauty for its own sake, as a surface to be admired. Burne-Jones’s own pronouncements give licence to this interpretation: ‘I don’t want to pretend that this isn’t a picture’; ‘Painting should be like a goldsmith’s work.’ Or, in his most otherworldly mode: ‘What eventually gets onto the canvas is a reflection of a reflection of something purely imaginary.’ Still, his current defenders seem to concede too much. ‘I want big things to do and vast spaces,’ Burne-Jones remarked, ‘and for common people to see them and say Oh! – only Oh!’ Insofar as there were any common people at the Tate when I visited, there were plenty of ‘Oh!’s, with quite a few ‘ooohs’ and ‘aaahs’ mixed in. Pleasure seems to be the element missing from those academic responses, however well intentioned. What is there to warm to in Burne-Jones’s mature work? And if his Burne-Jonesiness is an obstacle, what might lie behind it, or around it?

One way of answering this question is by asking a simpler one: what was Burne-Jones good at? Animals, it turns out, or birds at least. The ones that hop among the briars in Love and the Pilgrim (1896-97) are chirpy customers – nearby in the exhibition are some of his very likeable preliminary sketches of them on the wing. (Come to think of it, there’s a nicely doleful donkey in the Brighton altarpiece.) Also feet. The Golden Stairs (1880), which depicts 18 near identically dressed maidens descending a curved golden staircase, is one of his weirdest and most celebrated paintings, but it’s the feet that stand out. ‘I have drawn so many toes lately,’ he told its future owner, ‘that when I shut my eyes I see a perfect shower of them.’ The toes bend and squidge appropriately – again, the preparatory studies are charming – but it’s the orchestration that does it. At the top of the stairs five knees are gracefully turned to the right, lower down four are turned to the left. It is a sinuous swoop of a picture, sashaying towards the viewer waiting at the bottom, where you see four left feet, each on their toes, on successive steps.

Burne-Jones was good at colour, something we overlook because he wasn’t ‘painterly’ in the obvious sense. The naked bathers in the background of The Mill (1870-82) – prompted by Piero della Francesca’s Baptism of Christ (1448-50) – are a lovely ruddy pink, in a picture which is touched all over by the shades of an Italian evening, the sunlight dying on the water, leaching from the sky. Laus Veneris (1873-78), dominated by one of his most languid, androgynous women (Venus herself), is also a blast of boiling orange (her dress, an attendant’s cap), textured with gold, set off against deep blues and greens. In the third painting in the Briar Rose series (1885-90) – a rendering of the Sleeping Beauty tale – the princess’s comatose maids (mostly their feet) are hazily reflected in a shimmering golden floor. (Burne-Jones was good at reflections – reflections of reflections of reflections of something purely imaginary.)

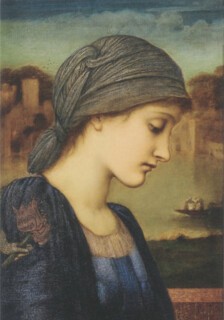

Then there are the portraits. Flamma Vestalis (1896), an imagined Renaissance study, is very fine, a delicate symphony in blue: the vestal’s powder blue headscarf tops a dress in two further, darker shades, with an exquisitely worked cuff; she holds a line of shiny blue-black beads, on a red string. The French writer Madeleine Deslandes (‘Ossit’) looks like a typical Burne-Jones beauty – pale and uninteresting – but move closer and you see that the portrait is made up of wonderfully balanced shades of blue, turquoise, grey, green; her eyes, hair and lips are chocolate brown on creamy skin.

Burne-Jones was good at line. ‘Line flowed from him almost without volition,’ the artist Graham Robertson remembered; Ruskin thought his ‘moving hand’ as ‘tranquil and swift as a hawk’s flight’. The odd insistence in some quarters that he couldn’t draw is belied by some of his portrait sketches, notably Desiderium (1873), of his lover Maria Zambaco in yearning profile (only improved by the ticklish suggestion that some scribbles in the margin represent a cock and balls, which she is reaching out to cup). It is also refuted by the marvellous caricatures with which he littered his letters: he himself appears always as a hunched, wizened figure with small black eyes, like a monkey; regularly dwarfed by Morris, looking like the Ghost of Christmas Present in the Muppet Christmas Carol. His friend Mary Gaskell was sent drawings of ‘The Fat Lady’, who in her black dress resembles a monumental tadpole, wriggling on a sofa or wallowing in a hammock. But his talent for line is also evident across the paintings: in the thorny branches that weave tortuously through the Briar Rose series, or loop the loop in Love and the Pilgrim; in the interlacing of Phyllis’s hair with the flowers blooming from The Tree of Forgiveness (a beefed-up version of the 1870 watercolour); in the drapery – one of Burne-Jones’s clearest debts to his Italian masters, Mantegna especially – that everywhere falls fluidly, whipped into peaks, creased into complexity.

Colour and line combine in his stained glass (it’s understandable there isn’t more of it to see in the exhibition, but still it’s a shame). Burne-Jones designed 786 windows for Morris and Co., in which he was a founding partner, between 1861 and his death in 1898; at least six hundred were produced, mainly for churches. ‘A window is colour beyond anything,’ he wrote, ‘but the leads are part of the beauty of the work and … the more of them … the deeper the colour looks.’ The Good Shepherd (1857-61), his very first attempt, done for the firm Powell and Sons, is almost dayglo in its intensity, the colours split and combined by a bewildering number of thick lines. Bright drops of blood run down the injured lamb’s leg, separately framed in lead, like ruby pendants. Two more lambs meander at the bottom; one tilts its head, a row of white teeth extending over a pink tongue. In Lot and His Daughters (c.1874), a design done in chalk, a plume of smoke from the ruins of Sodom unfurls overhead, from one side of the paper to the other, itself contained within a thicker line, rising and falling like a wave. Lot’s wife looks back, paling into salt; the other three press on, their stooping profiles echoing the line of the smoke, their feet interlaced, predicting each other, as in The Golden Stairs. The Pelican in Her Piety (1880), another design (the finished window is in St Martin’s in Brampton, Cumbria), is possibly my favourite thing in the show. A splendidly geometric pelican (birds again), the curve of its neck and plunge of its beak framed between two raised wings, bleeds into the gasping mouths of her young; they crowd the top half of the composition, nested in a tree that winds implausibly from the bottom, culminating in a complicated plait of branches.

Burne-Jones was good at perspective. Not in the classic sense, but his pictures play interesting tricks. The Wheel of Fortune (1883) is ludicrous, but triumphantly so. Fortuna stands massively on the left, in sculptural drapery, turning the wheel, on which three Michelangelo-esque male near-nudes are strapped, or stacked, from the bottom to the top of the frame (it is enormous but relatively narrow, 2.6 metres tall and 1.5 metres wide). It’s because the component parts refuse to come together, almost like collage, that it works. In Laus Veneris, Venus’s chamber is a shallow space, almost entirely covered in a tapestry; it extends back into another, shallower one, decorated with blue tiles, then to a window, which opens onto a hedge; beyond that can be seen Tannhäuser and his knights, who peer over it; behind them is a mountain range, and behind that the sky. These multiple, diminishing views – frames within frames – give the impression of depth while simultaneously denying it: you never forget you’re looking at a picture.

Once you notice this effect, of depth that is present but also foreclosed, you see it everywhere in Burne-Jones’s work. In The Mill, the building itself is almost Brutalist, and still more unusual in the number of openings and entrances it presents to the viewer. I counted 14 arches in the picture, not including reflections, or the three water wheels. There are mysterious sources of light: two slits between the central group of women, and a glow further to the right, as well as a reflection of a tree on the water which seems to derive from nowhere. In a portrait of his daughter Margaret, the darkened mirror behind her head shows a window at the other side of the room, apparently the only source of illumination. Is it part of the claustrophobia induced by looking at Burne-Jones, especially in the mass, that escape routes are always in evidence, and forever out of reach? It might be a metaphor for the niggling problem of his Burne-Jonesiness. He was good at many things; there are pleasures to be had. But love him? I’m trying to find a way.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.