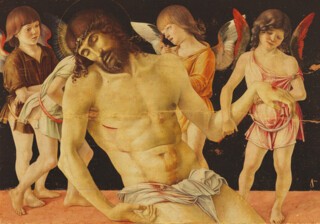

The six rooms at the National Gallery filled with works by Bellini and Mantegna are a once-in-a-lifetime feast. My reaction in the show was mainly wonder, mixed with incredulity that so many paintings, often so fragile or so much the pride of their place, had been allowed to travel to London. Then a slight sadness mixed with my first elation. It struck me as strange not to have to press my way to such treasures through a great crowd of people. And it came home to me that there was once a time, not too long ago, when painting of this kind – The Dead Christ Supported by Four Angels from Rimini, the classic dialogue between Bellini and Mantegna’s versions of The Agony in the Garden, the grisaille Lamentation sent (miraculously) from the Uffizi – had been a touchstone, a battle-cry, part of the life world of modernism. Phrases from The Cantos sounded in my head:

a wall

Here stripped, here made to stand.

Drear waste, the pigment flakes from the stone,

Or plaster flakes, Mantegna painted the wall.

Silk tatters, ‘Nec Spe Nec Metu’.

And always behind the melancholy informing these modernists’ deep love of the quattrocento lay the judgment of their 19th-century fathers. That judgment too was alive for me. I remembered Ruskin on Bellini:

The art of Bellini is centrally represented by two pictures at Venice: one, the Madonna in the sacristy of the Frari; the second, the Madonna with four saints, over the second altar of San Zaccaria.

In the first of these, the figures are under life size, and it represents the most perfect kind of picture for rooms; in which, since it is intended to be seen close to the spectator, every kind of finish possible to the hand may be wisely lavished; yet which is not a miniature, nor in any wise petty or ignoble.

In the second, the figures are of life size, or a little more, and it represents the class of great pictures in which the boldest execution is used, but all brought to entire completion. These two, having every quality in balance, are as far as my present knowledge extends, and as far as I can trust my judgment, the two best pictures in the world.

The Frari and San Zaccaria altarpieces are too precious and vulnerable ever to be moved (I illustrate the panel from the Frari). There are in any case fine equivalents in the National Gallery show. The steady inner light that bathes the Bellini Madonna and Saints lent by the Accademia, for instance, gives a sense of the Frari Madonna’s grave atmosphere, especially in its handling of Mary’s grasp on the child; and the Uffizi Lamentation points forward, in its very different medium, to the economy of touch and implacable pictorial silence of San Zaccaria. Or from an earlier phase – another loan of improbable generosity, given the painting’s size and past sufferings – there is the ten-foot-long Lamentation from the Doge’s Palace. I realise that Pound’s desolation and Ruskin’s idolatry in relation to painting of this kind will grate on many readers, but I’d like to defend them while the spell of the show is fresh – at least the hero-worship and sense of loss.

The first room of the exhibition brings together a Mantegna Presentation of Christ in the Temple from Berlin, done in egg tempera around 1454, and a Bellini of the same subject in oil on canvas, painted twenty years later, now owned by the Querini Stampalia Foundation in Venice. Mantegna seems to have been still in his early twenties when he made the original work. He had just married Bellini’s sister, Nicolosia. Mantegna had worked mainly in Padua up to that point and had already done painting that many thought the most brilliant and learned of its time. The Bellinis must have been pleased to make such a prodigy a member of the family. The Presentation of Christ in the Temple seems to have established itself as a clan treasure – in all likelihood the two smaller figures attending right and left are Nicolosia and Mantegna himself. Maybe the decision on Bellini’s part to do the canvas again was sparked by the arrival of a new baby or a betrothal in the family at large – it has been suggested that the image Mantegna did in 1454 had functioned as an ex voto following childbirth. Bellini clearly started from a deep love and respect for the older painting. He follows the conformation of the central group with utter faithfulness: beneath the surface of his oil paint there is apparently a careful tracing. But of course he has added more figures. The new medium is decisive. Space is different – the proximity of the figures to us, the light that touches them, the space circulating within the tight group, the height and emptiness of the background. Bellini’s painting is a meditation on its prototype, and therefore – thereby – a further meditation on the scene as narrated in St Luke’s Gospel.

We tend to take for granted the originality of Mantegna’s conception. Perhaps we have lost earlier inventions by other hands, but as it now stands his painting is inaugural: it invents a type of image that hovers between telling a story and stopping the story so decisively in its tracks, stilling it and bringing it close to us, that the exact play of attention between the actors involved – their arrest, their witness to the sacramental meaning of the moment – overtakes any trajectory of before and after. The old man on the right is Simeon. ‘He came by the Spirit into the temple,’ according to Luke, and took up the child in his arms, saying: ‘Lord, now lettest thou thy servant depart in peace, according to thy word: For mine eyes have seen thy salvation.’ But Simeon also says, this time directly to Mary: ‘Behold, this child is set for the fall and rising again of many in Israel; and for a sign which shall be spoken against; (Yea, a sword shall pierce through thy own soul also,) that the thoughts of many hearts may be revealed.’

It is a terrible and wonderful passage. Eliot in his ‘Song for Simeon’ retained the strange parentheses surrounding the warning to Mary: ‘(And a sword shall pierce thy heart,/Thine also).’ I believe – and this is one main way I follow in Ruskin’s footsteps – that both Mantegna and Bellini were alert to every difficult turn and rebalancing in Luke’s verses, and thought hard as they painted about how to convert such turns into touches, faces, ways of looking and holding, intervals between people, ‘drapery’ (a word whose matter-of-factness conceals, in the greatest artists, metaphor after metaphor of human strangeness), proximity, ‘expression’. Ruskin, in his pages on Bellini, goes on to assert that ‘the third attribute of the best art’ – the first two are consistency of workmanship and perfect serenity – ‘is that it compels you to think of the spirit of the creature, and therefore of its face, more than of its body’. The ‘more than’ here strikes me as wrong: as much is conveyed by Mary and Simeon’s hands and arms, or the set of necks on shoulders, as by their mouths and eyes. But the faces are triumphs – Ruskin is right. In them, but also in the whole play of bodily acceptance and withholding, everything Luke’s words suggest is made manifest.

Bellini was probably even younger than Mantegna when he first saw his new relative’s Presentation of Christ in the Temple – art historians will never stop worrying about his exact birthdate. (He may have been Jacopo Bellini’s illegitimate son. Records are scarce. Mantegna was the child of a carpenter, from a very ordinary village. His birthdate is also unknown.) When Bellini turned back to The Presentation of Christ in the Temple twenty years later he was the master of a new style, and dialogue with Mantegna had established itself as an aspect of that mastery – his great Agony in the Garden, done in response to a panel by his brother-in-law, lay behind him. It is hard, therefore, not to see the redoing of The Presentation of Christ in the Temple as some kind of contest as well as homage. But I found myself as I looked convinced that for Bellini what counted most was the opportunity, within the confines of someone else’s invention, to reflect on – to discover – what his own art most deeply consisted of. Oil paint versus tempera made many things clear. And, further, coming to terms with the true nature of one’s art – one’s necessary medium – meant coming closer to the mysteries enounced in Luke’s text.

It is easy to prefer Bellini’s revision. Conservators tell us that the black background in Mantegna was likely a deep blue in the first place, and that the geometric haloes were altered later by an unknown hand, so we cannot be sure how they conjured space originally. But Mantegna’s figures must always have been near, pressed close to the surface, hemmed in by the painted marble of the frame. Bellini’s scene is moved back a little, beyond a cooler darker parapet.

The ceremonial pillow on which the Christ child is standing no longer spills into our space. The background has become a positive void. Light is attached to each forehead, cheek and neck, and moves each face it touches just a little further into three dimensions – look at the face of Joseph, attending warily to the main protagonists – but ‘modelling’, as a term of art, is entirely inadequate to what takes place. Light in the central grouping seems as much an emanation from a solid as a flood of photons across it. Mary’s neck and head are incandescent. Light, as Bellini manages it, exposes the Virgin, we might say, just enough; not cruelly or relentlessly; not insisting on her youth or delicacy or translucency, but nonetheless preparing her for the sword that pierces. Mantegna’s Virgin is more a thing of this world. Mary’s neck in Bellini may help to explain the effect; and the very slight additional fullness and redness of her mouth.

Compare the two faces of Joseph (‘And Joseph and Christ’s mother marvelled at those things which were spoken of him’). Look especially at the eyes. Bellini is almost arrogantly swift, summary, ‘open’ in his redoing of Mantegna’s original quizzical misgiving. He steps back from ‘expression’, if by that we mean specific action and reaction, or readable state of mind. Bellini by 1470 is part of a painting culture in Venice that has thoroughly internalised the idea that less is more, and that the brushmark does well to leave some things sufficiently unclear – as the word does in Luke. Maybe Simeon is taking the Christ child to be circumcised, so that part of the story is simple parental concern. But Simeon’s tenderness in the text is indubitable and Mantegna is wonderful in his translation of this. Bellini, his attention caught by a different aspect, seems to have thought intensely about how to balance attentiveness and puzzlement in Joseph’s face, even the trace of fear. The figure is allowed just a tad more space between the child and Simeon, the light pulling him closer, the line of his shoulder given a different (more stable) gradient. He acts as the viewer’s alter ego. Maybe that is why Bellini seems to have lost interest in the other onlookers.

Mantegna’s version remains a staggering achievement. You turn back to it from the Bellini and fall under the spell of its maker’s endless appetite for stuff, for pattern, for the rustle and ruck of surfaces. Simeon’s robe in Bellini goes dead. His beard no longer enacts his tact, his gentleness. His mouth forfeits its weary smile. Bellini can do no more in the face of Mantegna’s astonishing conversion of the plates and fissures of a rockface (he was obsessed by geology) into the folds of Christ’s swaddling bands than repeat the perfect conceit. But look again at Christ’s head in Bellini! Look at what happens as a result of its slight diminution and the simplification of its cap. Look at what light does to the intersection of child’s cheek and mother’s forehead. Surely everything in the story depends on Christ’s utter helplessness, yet total apartness – already launched on the path of ‘the fall and rising again of many’. Mantegna too is intent on this doubleness. His swaddling rockface is his way of putting it. Yet I think Bellini’s illumination of face and body – even his slight turning of Christ’s body in Mary’s hands – does more. ‘For a sign which shall be spoken against.’

The word ‘expression’ cropped up in my description just now and the scare quotes surrounding it point to a problem. The achievement of some of the very greatest artists turns on aspects of visual experience that are specially hard to put into words. We know, for example, that Bellini’s view of the world depends on light, and that his particular handling of illumination in relation to inner consciousness seems to propose – and over his final three decades to develop through a formidable sequence of changes up to the final Drunkenness of Noah – a whole ontology. Ruskin’s unwelcome word ‘spirit’ and its constant companion ‘soul’ do seem called for. But how much further can we go? My tired metaphor ‘inner light’ may be just defensible, but to the extent that it conjures up some metaphysical bag of tricks in painting, it leads, with Bellini, in precisely the wrong direction. In Bellini’s art simple visibility is all. Light discloses, it does not flicker and penetrate.

Turn back with Ruskin to the main panel of the Frari altarpiece. The panel has many glories: even in reproduction the viewer can pick up the soft dazzle of its half-dome and brocaded back wall, and glimpse the pilasters and capitals leading to them, which are those of an open loggia two bays deep. Saints stand in the panels on each side, and three of them look through the pilasters at the Virgin on her throne. It is a triumph of spatial compression. But the central achievement of the altarpiece is one art writers prefer on the whole not to mention, certainly not to talk about at length – the face Bellini has found for the Virgin and the character of her relation to Christ. Even to pose the matter as a ‘problem’ seems embarrassing. What would it have felt like to be the mother of God? And how would that feeling, or play of contradictory feelings, have registered in comportment, a ‘face’ presented to the world? What sort of equipoise or entwinement would there be in the Virgin – of pride, say, and diffidence, and acceptance of herself as a vehicle (an incarnation) of the future Simeon warned her of?

Bellini’s thinking on the subject is formidable. The direction of Mary’s look seems key. (It has partly to do with her factual position above us as we stand in the Frari chapel – the panel must always have been placed above the altar – and partly to do with her height within the illusion, standing on a marble plinth.) Her ‘look’ defies language. And that is part of the theology, presumably: the proper look of the Virgin must surely include an element of not understanding. Yet failing to understand one’s place in a scheme of salvation does not, in Bellini’s hands, mean that her face – her person – retreats into the realm of the numinous. Mary’s face is as ordinary, as plainly present, as ever a face has been. The mouth and raised eyebrows bring everything down to earth. The accidental pucker of the kerchief on her forehead is to be considered in the light, but also against the light, of the whirling halo just above, off to one side in the frieze on the half-dome.

And we have hardly begun to assess the balance of forces, the kinds of contact, between mother and child! Christ has come out of his swaddling bands … What we are looking at is collaboration, no doubt, a sharing of powers; but also, as the gospels tell us, a battle of wills.

There are , as I have said, paintings in the present show almost as resonant as that in the Frari. Bellini’s Virgin and Child with Saints Catherine and Mary Magdalene from the Accademia is one, and his Madonna of the Meadow (c.1500) another. One of the very few quarrels I have with the beautifully installed set of rooms is the decision to relegate the Madonna of the Meadow to a somewhat dismal corner. I understand the National Gallery’s sensitivity to the charge that its exhibitions have sometimes made too much of its own paintings. Visitors are presumed to know them already. But we do not know the Madonna of the Meadow as it might look next to the Accademia panel or across from Mantegna’s Dresden Holy Family (c.1495). Is it too much to ask that, for the last weeks of the show, their prime late Bellini is moved to a place among its peers?

The exhibition is a feast and there are many aspects of it I have left to one side. Room Three is a cabinet of wonders, where the interplay between painting and sculpture – between painting that looks back across the decades to Donatello, and a beautiful piece of sculpture by a bronze worker operating in Mantegna’s orbit – is breathtaking. Bellini, the show reminds us, is an artist of enormous range: our picture of him is distorted by the loss of the long sequence of history paintings he did for the Doge’s Palace. Here one is struck by his easy affinity, when circumstances were suitable, for an outright erotics of devotion. Some say The Dead Christ Supported by Four Angels was painted for Carlo Malatesta, grandson of Sigismondo Malatesta, Pound’s merciless culture hero. The picture has the Malatesta fire about it – it is a strange mixture of the heart-rending and the lavish. Look for instance at the angel in white to the left of Christ, wearing a twisted pink sash at his waist which rhymes with the wound on Christ’s side. The boy is a fetching concoction: his white tunic slashed to reveal a touch of thigh; his head disappearing behind Christ’s, borrowing Christ’s curls as they fall on the shoulder; one hand supporting Christ’s armpit, one knee in dialogue with a dislocated elbow. And look at the exquisite stroboscope of Christ’s halo – blue wing tips outlining its circular rim, white feathers inside it; the halo itself a spinning-wheel transparency, with Christ’s crown of thorns as tidy as the curls his thorns turn into. ‘The filigree hiding the gothic,/with a touch of rhetoric in the whole.’

Mantegna suffers more than Bellini from the show’s inevitable absences. The frescoed scenes in the Camera degli Sposi in Mantua, moving through registers of good humour and compassion, sound a note of humanity in his career, which raises his art to a higher power. Even the pale ghost of the frescoes in the Church of the Eremitani at Padua speaks to a young man’s love-hate affair with Rome in a way that he never quite matched on a smaller scale (the uncared-for walls Pound saw in the 1920s, which I think are what he means by the ‘pigment flakes from the stone’, were bombed into ruin in 1944). The great Triumphs of Caesar done at the end of Mantegna’s troubled life, three of which have been brought to the show from Hampton Court, come across as a bitter unrepentant hymn to Rome’s chaos of plunder and cruelty. The whole world of ‘the antique’ in elderly Mantegna seems more and more associated with the malformed, the vicious, the cretinised. Drawings swarm with monsters – monsters without dignity. Envy and calumny are favourite themes. It is clear that these nightmares were, among other things, his commentary on his time, on the Gonzaga court in Mantua that had treated him badly; their picture of politics never goes out of date.

Turn from such obscenities to The Drunkenness of Noah (c.1515). Old age can be comedy, not a battle with ghouls. The painting may have been the last Bellini did. It is an old man’s dream of death with indignity – a farewell to high seriousness, an anti-Pietà. Shem, Ham and Japheth cackle and cringe at the sight of the naked patriarch. (Ham’s bad teeth are a touch of genius.) Noah rests light on his pillow of stone. Or look at Bellini’s Resurrection from Berlin. Follow the aqueous flow of the cliff-face, like the head of a toad still wet from the swamp. And then register – it takes time for the shape to surface – the enormous hard-edged cube of granite inside the darkness of the tomb, mass brushed aside by miracle. The flow of rocks, the impotent geometry. How these painters loved both!

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.