When the American artist Bruce Nauman was in graduate school in the mid-1960s, the traditional forms of visual art were in deep trouble. The best new work, the Minimalist Donald Judd had asserted, was neither painting nor sculpture, and he was hardly alone in that judgment. So what might serve as a medium in default of the usual ones? What might count as art at all? In 1917 Marcel Duchamp had declared that art is whatever the artist names as such. Fifty years later Nauman held that art was whatever an artist did in his studio, ‘pacing around, for example’, and in lieu of painting or sculpture the body might be ‘a place to start’. In this way Nauman turned a negative condition into a positive possibility. ‘I have nothing to say and I am saying it,’ John Cage wrote in 1949; two decades later Nauman said, in effect, ‘I have nothing to do and I am doing it.’ Although this formulation isn’t as dire as ‘I can’t go on, I’ll go on,’ Nauman does share with Samuel Beckett (another early influence) a wicked sense of stark humour. In his short film Square Dance (1967-68) Nauman steps around a rectangle taped on his studio floor in a deadpan manner that both parodies the modernist obsession with this geometric form and opens up the Minimalist grid to bodily movement.

For Nauman ‘art became more of an activity and less of a product,’ a shift that aligned him with contemporaries such as Richard Serra and Eva Hesse as well as choreographers like Yvonne Rainer and Trisha Brown, who refreshed dance with everyday gestures and basic tasks. At the same time, as Anne Wagner has argued, Nauman held on to historical sculpture as a ‘shadow antithesis’ and undid ‘the outworn ethos of monolith and monument’ from the inside. The demythologising of this ‘outworn’ art carried over to the figure of the inspired artist; failure is a persistent theme in Nauman. An early photograph titled Failing to Levitate in the Studio (1966) shows Nauman collapsed between two chairs – no transcendence here – and an early neon piece turns a lofty sentiment, ‘The true artist helps the world by revealing mystic truths,’ into a kitschy sign.

Although Nauman relies on his own body, his presence is not guaranteed. Long ago he declared his interest in ‘withdrawal as an art form’, and his retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art (until 25 February 2019), curated primarily by Kathy Halbreich, is titled Disappearing Acts. Even when Nauman offers his own measurements, as he does in Neon Templates of the Left Half of My Body, Taken at Ten-Inch Intervals (1966), it is absence that is conveyed. This is also the case with Wax Impressions of the Knees of Five Famous Artists (1966), only here the non-presence is complicated further by deceit: this frieze punctuated by five indentations is made of fibreglass and resin, not wax, and the marks are Nauman’s own, not the auratic relics of great visionaries. At the same time his corporeal substitutes often evoke the body all the more – the chair is his favourite ‘stand-in for the figure’ – and this is the case too when Nauman shapes other voids, as in The Cast of the Space under My Chair (1965-68). The concern with ‘the underside and backside of things’ also became central to his early work.

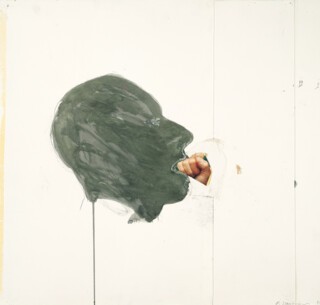

Many artists in the 1950s were enamoured of the readymade, but not Nauman in the 1960s, or, for that matter, Serra or Hesse. Again, they stressed process over product, which led them back to Jasper Johns, who not only foregrounded art as making but also used simple devices like stencils and rulers in that making. In addition, Johns pointed Nauman to late Duchamp, who cast various parts of the body, a cue that helped Nauman get around the precedent of the Minimalist object. In 1959 Duchamp made a plaster cast of the right side of his face, added a drawing of his profile, and called it With My Tongue in My Cheek; in other words, he took a phrase for saying one thing while meaning another and literalised this definition of irony. Nauman tried his hand at this impossible reducing out of linguistic ambiguity in several works, such as Henry Moore Bound to Fail (1967/70), an iron cast of two arms tied behind a back, From Hand to Mouth (1967), a wax cast of just this length of the body (the model wasn’t Nauman but his wife), and Feet of Clay (1967/70), a photo of his extremities lightly modelled in that earthy material. ‘Sometimes it’s necessary to state the obvious’ is one moral that Nauman learned from Johns, but the actual lesson here is that meaning is never simple – a basic idea that Johns passed on to Nauman through his reading of Wittgenstein as well as Beckett (Ed Ruscha took this point too).

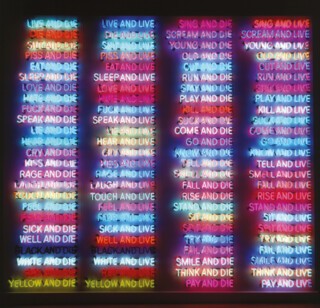

As Nauman acknowledged in an interview in 1984, ‘there’s a kind of restraint and morality in Johns’ that he admired. Leo Steinberg once described this posture as one of ‘sufferance’ before the world, which appeared to press on Johns’s passive art almost directly. Nauman transformed this sufferance into resistance: ‘doing things you don’t particularly want to do … to find out why you’re resisting’. In this way his bodily actions took on an emotional charge, and his studio became a stage for a psyche turned inside out. ‘Anger and frustration are two very strong feelings of motivation for me,’ Nauman admitted, and in the 1970s his work did take on a violent edge. Aggression came to the fore – a 1973 lithograph declares (in reversed script) ‘Pay Attention Motherfuckers’ – as did the relay between sadistic and masochistic impulses: ‘Help Me Hurt Me’ reads a lithograph from 1975. His neon pieces flash binary warnings to the effect that we are all trapped in basic oppositions of life and death, domination and submission. His stick figures, also in neon, grind away at each other in mechanical acts of torturous sex, while his Hanged Man (1985) alternates between being alive-and-erect and dead-and-limp, as if life and death were a simple on-off switch. Nauman locates this aggression in humour and sexuality, but he also intimates that it is loose in the media and politics all around us. One neon sign from 1981-82 flickers in sequence: ‘violins violence silence’.

Nauman did not restrict this theatre of cruelty to the human realm. In 1979 he moved to a ranch in New Mexico, where he initiated a new branch of production: carousels hung with animal dummies, always bare and often cut up, that slowly rotate in an endless circuit. At the same time Nauman suggested that this disassembly hell had ample slots for humans too. Starting in the early 1970s and continuing in this period of neo-imperial adventures under Reagan and Thatcher and authoritarian crackdowns by other regimes, he conceived steel cages, claustrophobic corridors and underground tunnels, some of which were equipped with video monitors. An oppressive sense of discipline and punishment, security and surveillance, pervades this body of work. South America Triangle (1981), which features a cast-iron chair suspended upside down within a large frame of steel beams, conveys more than a hint of political torture, while Learned Helplessness in Rats (Rock and Roll Drummer) from 1988, which consists of both a maze and a live video of a rat in the maze made frantic by the percussive beating of a punk drummer, suggests a kind of scientific abuse that cuts across species. Here Nauman shows how thin the line is between perceptual experiment and behaviourist manipulation.

How are these different registers of violence – psychic and political, technological and scientific – connected? For Nauman they are all rooted in a fundamental splitting of the self. Almost in a Lacanian way he intimates that our mirror image, however coherent and intimate it might appear, is actually divided and alien, and that narcissism easily flips into aggression. When video art first emerged, Rosalind Krauss theorised it in terms of ‘an aesthetics of narcissism’, but early adopters like Nauman discovered that the relay between camera and monitor, self and image, is always delayed and sometimes broken, and that the medium is suited to rupture more than repletion. As in Beckett soliloquies that dissolve the self rather than declare it, Nauman explored this breaking up of body and ego alike (‘Make Me Think Me,’ a drawing from 1993 exhorts). As you walk down one of his corridors with a camera behind you and a monitor in front, your image gets bigger, not smaller, and you feel discombobulated by your own appearance. Nauman messes with his own image too. In a series of videos he takes the epochal animation of the body named by the word contrapposto – when the lively Greek kouros emerged from its static Egyptian precedent – and demonstrates how visual media confound the figure instead: Nauman is doubled, reversed and fragmented here, not humanistically enlivened. Divided by our image, let alone by our unconscious, we are never self-same, and Nauman suggests that this splitting is compounded technologically and politically: again, aggression and anomie are in us and all around us at the same time. In many ways this confusion of inside and outside is the great subject of his un-funhouse art.

This work hardly needs a silver lining – it is anti-redemptive after all – but an unexpected one can be extracted nonetheless. Twenty years ago MoMA staged a large Nauman show, and two moments stick in my memory. In the first instance I followed a young woman into a constrictive space lit in harsh yellow in which a male voice repeated ‘Get out of the room, get out of my mind.’ We listened together for several minutes, made uneasy by the situation; finally, as she left, she muttered under her breath, ‘I had a boyfriend like this once,’ and we both burst out laughing at the miserabilism of men. The second moment involved watching my two sons, young at the time, delight in a two-channel video titled Good Boy Bad Boy (1985), in which a black man and a white woman conjugate, at times sweetly, at other times furiously, such verbs as ‘shit’ and ‘fuck’: ‘I shit, you shit, we shit, this is shitting …’ The boys found it hilarious, scandalous, and scary all at once, and I like to think that they intuited a weird commonality there, which we used to call the human condition. For Nauman our humanity is steeped in misunderstanding and cruelty, and it is as though he aims to humanise us through the bits of our being that often seem the most inhuman – base bodily acts and baser psychic rages.

I suppose it is fitting that work devoted to splitting would be divided between two sites – MoMA in Manhattan and MoMA PS1 in Long Island City – but this arrangement makes it difficult to grasp as a whole, as does the non-chronological presentation. Also, given that some pieces are designated as ‘leftovers’, and others model spaces that seem as virtual as they are actual, the exhibition can feel a little inert – so many things scattered in a field, like the props of a performance that we have missed. Then there is this paradox: not many of the pieces are true knockouts – Nauman is masterpiece-averse – yet he is massively influential nonetheless (his friend Serra considers him the most important artist since Warhol). One sees connections to numerous artists, male and female, in my own generation, such as Cindy Sherman (who also stages a self that is not one), Jenny Holzer (who also delights in contradictory messages), Mike Kelley (who also probes the pathetic underside of men), Robert Gober (who also presents the body image as divided, even damaged), and Doris Salcedo and Mona Hatoum (who also evoke spaces of social anomie and political violence). And the influence extends to the next generation as well, with Matthew Barney (art is what the artist does in the studio), Rachel Whiteread (casts of negative space), Claire Fontaine (neon alarms), Rachel Harrison (sculpture as anti-idealist contraption), Nicolás Guagnini (psychosexual contortions), and so on.

Nauman is ‘anachronic’ in the sense that he anticipates subsequent artists who then reposition him in turn. He presaged the fascination with abject states and troubled masculinities in the 1990s, and was concerned with surveillance long before 9/11. Then, too, there is no more autofictional artist than Nauman, and his theatre of cruelty, in which impotence triggers violence in a nihilistic way, seems to play out daily in the news. Finally, there are his clown videos. In one piece a clown repeats (as if stuck) the opening of a ghost story: ‘It was a dark and stormy night.’ Could that be Trump behind the face paint? In another a clown on the floor kicks and screams: ‘No no no …’ Is that us?

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.