The Swiss artist Sophie Taeuber grew up without a father. Carl Emil Taeuber, a pharmacist, succumbed to tuberculosis in 1891, two years after her birth. Her mother, another Sophie, never remarried. Instead she moved back to Trogen, her birthplace, and designed a new house for her young family; supervising its construction, planting and tending its garden, and looking after a series of paying guests. She taught her two daughters to sew, knit, crochet, embroider, quilt and make lace. In her spare time, such as it was, she learned photography, including processing and printing. Then, in 1906, she fell ill. Two years later she was dead.

Roswitha Mair’s biography of Sophie Taeuber, first published in German in 2013, delves into a range of unpublished sources, not only those held at the Fondation Arp in Paris, but also those still in the keeping of the Taeuber family, among them her elder sister’s letters and diaries. This trove – it even includes the original plan for the Trogen house – is especially helpful in building a picture of Sophie’s early life. According to Mair, Sophie’s mother installed in her daughters an unwavering belief in the value of working with their hands – a legacy captured in the book’s German title, Handwerk und Avantgarde. It was Sophie’s own decision, however, to tie these domestic skills to a career in design. At 18 she became a student at the drawing school run by the Industrial and Weaving Museum in St Gallen, a city whose textile industry was founded on the mechanisation of traditional local embroidery. The teachers encouraged the study of ornament, as well as emerging artistic trends. For Taeuber, this meant the paintings of Gauguin and the Nabis, the work and thought of William Morris, and the radically reductive patterning seen in tribal art. In 1910 she moved to Munich to attend the Teaching and Research Studio for Applied and Fine Arts, known as the Debschitz School after its founder, Wilhelm von Debschitz. He too took his pedagogical principles from Morris, and offered instruction in furniture design, textiles and metalwork – all fields that, by the end of the decade, the Bauhaus would also embrace.

Among the artists in the circle around Debschitz were the sculptor Clara Rilke-Westhoff, the painter Gabriele Münter, and Münter’s teacher and sometime lover Wassily Kandinsky. No longer students – all three were at least a decade older than Taeuber – these artists formed Der Blaue Reiter, a precursor to German Expressionism. Yet their forays into abstraction seem to have been less important to Taeuber than her encounters with contemporary dance. When Isadora Duncan performed in Munich, she was in the audience. After war broke out in 1914, she moved to Zurich, where she joined Rudolf von Laban’s dance school and became a key member of his troupe.

In the early years of the war Zurich was home to a rapidly coalescing avant garde. This soon became Dada, as enacted nightly at the Cabaret Voltaire; it meant noise and nonsense taking over from, or as, music and poetry; it meant an international assortment of viewers and performers, many of them conscientious objectors. Among these artistic exiles was Hans Arp, a French-German painter who had escaped from Germany on the last train to France. He was lucky not to be arrested as a German spy. In May 1915, he arrived in Zurich, where he met Taeuber. As the painter Hans Richter put it, ‘She was Arp’s discovery, just as he was hers.’

Both Taeuber and Arp found a place among the Zurich Dadaists, though she was the more visible of the two. Along with Mary Wigman and Emmy Hennings, she was recruited to dance in the Dada cabaret. Barefoot, often masked, the performers moved alone or together in response to the sounding of a gong. According to Hugo Ball, author of the Dada Manifesto and cofounder of the Cabaret Voltaire, a Dada dancer’s nervous system and ‘hundred-jointed body’ was able to ‘exhaust’ every tremor of sound. Not every dancer could work such magic. One performance saw dancers moving to ‘Karawane’, Ball’s scandalous sound poem, which begins: ‘Jolifanto bambla o falli bambla/großiga m’pfa habla horem.’ When Ball himself intoned these nonsensical syllables, he stood before the audience as rigid as the Tin Man, ensheathed in tubes of silver-painted cardboard. The poet Tristan Tzara described Taeuber’s performance in the same piece: a ‘delirious oddity in the spider of the hand vibrates rhythm rapidly rising to the paroxysm of a mocking capriciously beautiful insanity’.

Mair reproduces a marvellous photograph of Taeuber posing in the outlandish costume she and Arp created for her performance: arms held stiff in cardboard tubing, swathes of paper suggesting a skirt and a tall rectangular African-style mask covering her face. It must have given the impression of a series of shapes set off in angular counterpoint, summoning a quasi-human creature out of tune with its world and its psyche.

Their friends said Taeuber and Arp, who married in 1922, complemented one another – his nonchalance versus her sense of focus – and on the whole Mair agrees. They began to work on collages together, cutting out paper shapes and placing them in arbitrary arrangements of blue, grey and black. But they had differing interpretations of the irrationality demanded by Dada. Arp claimed his famous torn paper collages were ‘governed by the laws of chance’ – laws exerted when in frustration he tore up a failed drawing and dropped the pieces on the floor. Looking at his collages it seems an improbable claim: their all too tasteful alignment of shapes suggests that chance had some assistance.

For Taeuber, chance was one of many techniques she used to connect her art with the world. Found glass beads (Mair tells us they came from a graveyard in Ticino) resurfaced in her sculpture; found paper was used in her puppets and collages. To encounter these thrifty habits is to be reminded of her childhood in a home governed by prudence and invention, but they also link to Braque’s and Picasso’s collages, which heralded a dissolution of the barriers between everyday skills and high-art practice. One of the most striking aspects of Taeuber’s handiwork is its bold reliance on radical abstraction to transform the look of objects women use and wear. Necklaces, dresses, collars, shawls, handbags, towels, pillowcases, carpets, lamps; inevitably, only a few of these eminently ordinary items survive. Yet each played its part in creating a transformed domesticity, each its own small world of vibrating colours and geometrical shapes. Can a domestic object seem alive? Almost everything Taeuber stitched or beaded seems vivified.

Some of the most revealing sections of Mair’s biography concern Taeuber’s work in design, particularly during the 13 years she spent as head of textiles at the Zurich School of Applied Arts. After the Armistice the Dadaists dispersed and Arp soon grew bored, leaving Zurich to return only intermittently. Taeuber stayed on, encouraging her students – whom Arp mocked for their burning desire to ‘neverendingly embroider floral wreaths on cushions’ – to abandon their conventional understanding of line and colour in favour of elemental forms. Memoirs by Taeuber’s students have provided Mair with an outline of her pedagogical principles. She began with simple exercises, encouraging students to experiment with wavy or zigzag lines, before putting different forms together, then introducing colour. These studies were transferred to different mediums, so that students learned the inherent properties of each: drawing became sewing, weaving, lacemaking, textile design and decoration. Technique, and an understanding of materials, would give rise, Taeuber believed, to formal variety that went beyond mere fashion. ‘In a flower, in a beetle,’ she wrote, ‘every line, every form, every colour has arisen from a deep necessity.’ This was the principle that lay behind her own commitment to geometrical abstraction across all her work in design, from cross-stitch compositions, each an easel-sized ‘tapestry’, to domestic interiors; from pieces of furniture to the décor of the Aubette in Strasbourg.

The works at the Aubette were a collaboration, begun in 1926 and completed two years later, that included not only Taeuber and Arp, but also Theo van Doesburg, one of the founders of the design movement De Stijl. The Aubette, an 18th-century building, was being remodelled as a modern leisure complex. The design of the tea room and the smaller bar fell to Taeuber, and with Arp she took on the entrance hall and a second bar. The other spaces, including a dance hall and cinema, were divided between Arp and van Doesburg. They all made use of the same basic motifs: ample light and mirrors; ‘modern’ materials such as nickel, plastic and rubber; and, particularly in the rooms taken on by Taeuber, rectilinear coloured panels in grey, black, red, blue and green. The owners, André and Paul Horn, were delighted and asked Taeuber to redo their apartment and a hotel lobby. Pleasure seekers, by contrast, stayed away. By 1930 the Aubette was neglected, and soon after it was abandoned, then whitewashed. In 2006, after thoroughgoing technical analysis of the panels, it was returned to its earlier state.

The implications of her time in Strasbourg go well beyond their concrete results. For both Taeuber and Arp, it presented an opportunity to carry out a major experiment. They wanted visitors to feel that they were inside a painting, and used colour as a means of inflecting the familiar right-angled regularity of interior space. Both took the opportunity to become French citizens, a step that soon led to Paris, and for Taeuber, a second architectural project. Following in her mother’s footsteps, she designed and oversaw the building of a house for them to live in on a plot of land in Clamart, on the outskirts of Paris (it’s now the home of the Fondation Arp). In a suburb of peaked pink tile roofs and smooth white plaster walls, Taeuber designed her house to have a flat roof and walls of rough ochre millstones unfussily cemented in place. The interior is light-filled and white.

At no point in her study does Mair swerve from Taeuber’s absorption in objects and images, friends and family to consider gender as a subject. It is the reader who has to recall that Taeuber didn’t have the vote, although she could work, travel, teach – and she did. When it came to the Aubette, Van Doesburg was disinclined to share credit with Arp, let alone his wife. Mair is rightly impatient with van Doesburg, while acknowledging that Taeuber didn’t seek the limelight. The contemporary sources Mair quotes show something of the condescension she must have faced. Die Frau als Künstlerin by Hans Hildebrant, published in 1928 ‘with 338 illustrations of works by women from earliest times to the present day’, takes Taeuber’s Aubette designs as proof that women can ‘at last design the décor of whole rooms’. Her ‘outstanding gift for abstract creations’, Hildebrant wrote, was coupled with ‘feminine capriciousness’. After they moved to Paris, Arp fell in with the Surrealists, while Taeuber stayed away. ‘She didn’t like the group dynamics,’ Mair writes. Fair enough.

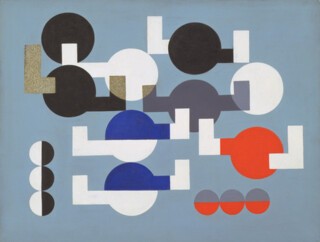

Is it the case, art historians have asked, that within modernism women only found a place as creative ‘partners’, helpmates, muses, technicians, always with the male artist in prime position? It wasn’t a role Taeuber was ready to accept. By the late 1920s Paris had become the centre of Surrealism and the home of a growing number of artists committed to geometric abstraction. There they formed and reformed under several rubrics – Art Concret, Cercle et Carré, Abstraction-Création – all of which were considerably more open to women than Surrealism. Barbara Hepworth was there, as was Sonia Delaunay. Taeuber was more committed than her husband to the new canons of form. In 1932, he wrote to friends in Basel: ‘Day and night my wife brandishes circle and line looks into the sky now and then where the beautiful visions come from smiles gratefully then brandishes circle and line once more.’ Taeuber was the one elected, in 1934, to Abstraction-Création’s executive committee.

Mair’s account of the impact of the 1930s on the two artists is inevitably fraught, not least because among those who turned to Nazism were people they both knew well. One of Taeuber’s former suitors, Adolf Ziegler, Hitler’s favourite painter, organised the notorious exhibition of ‘Degenerate Art’. Closer still was Rudolf von Laban, whom Mair presents as ‘receptive to German nationalism’, which seems to understate the case, given his role as choreographer of three national dance festivals. Ironically, in 1936 Laban lost out to Taeuber’s fellow dancer Mary Wigman, who was Goebbels’s choice to choreograph a section of the opening ceremony of the Berlin Olympics.

Closest of all was Sophie’s brother Hans, who worked in Munich trading in rare books. Not only did he turn a blind eye to Nazi confiscations, but as part of the ‘Aryanisation’ of Gilhofer and Ranschburg, a distinguished firm based in Vienna, he stepped in to purchase it using funds provided by Ziegler. Taeuber cut off her brother. She and Arp stopped speaking German, and used only French.

In June 1940, Paris surrendered to the German army and the Vichy government took charge. Taeuber and Arp had left the city shortly before, making their way slowly south, before stopping at a borrowed château in Grasse. In August 1942 the house was commandeered; its owner was allegedly a Jew. On 11 November, German troops marched into the French unoccupied zone. Taeuber and Arp arrived in Zurich three days later. She was soon back at work on prints for a portfolio titled 10 Origin, to be published by their friend Max Bill. Not long after their arrival, she was asphyxiated by fumes from a faulty stove at Bill’s house. Hans Arp lived for another 23 years, promoting his wife’s work while also taking the astonishing step of employing the artist Lilli Erzinger, whose work he thought resembled Taeuber’s, to complete her unfinished pieces. This decision seems misguided at best – it had the effect of erasing Taeuber from the work.

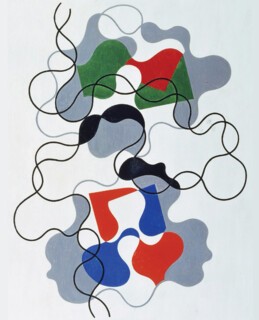

Mair reproduces two striking examples of her finished ‘late’ pieces: Summer Lines, an oil of 1942, and Lines, Geometrical and Wavy, a coloured pencil drawing made a year earlier. In both works, space seems vast and at the same time entirely absent. Lines twist and turn, then come to a halt. Pale echoes of their movement seem to lie beneath the image surface, as if to suggest another dimension. These works are at a real distance from Taeuber’s Cercle et Carré abstractions of a decade before, the ones Arp called into question. There is nothing mundane about their elusiveness. In the dark days of the Second World War, Taeuber was trying to find a new horizon for abstraction.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.