The photographer Sanlé Sory was born in the 1940s in French West Africa. At independence in 1960 he became a ‘Voltaic’, or a citizen of Haute Volta, and in 1984, a ‘Burkinabe’: the new head of state, Thomas Sankara, had combined two non-colonial languages to rename Haute Volta as Burkina Faso, ‘the land of the upright’. By then Sory’s work had consigned him to the land of the slightly stooped, gazing through the viewfinder or bent over the developing tray, even though in his self-portraits he is a paragon of ‘uprightness’, short and muscular, with an obvious liking for the gym. Within a few years of independence he was running a studio in Bobo Dioulasso, 350 km west of the capital Ouagadougou, and building up a remunerative sideline putting on dance parties and doing artwork for vinyl recordings by Burkinabe musicians. Many of his negatives and prints have survived, and so has he. Recently his work has been shown at the Cartier Foundation in Paris and the Art Institute of Chicago. A small exhibition at the Arts Club in Dover Street (until 31 January, by appointment) gives a good idea of his studio portraits, despite the fact that the prints – twenty or so – are on display in a room that serves them badly. Most are hung way above head height: a set of library steps would have come in useful, but a pain in the neck just about does the trick.

Sory’s interest in photography began when he had to get himself an ID card, an obligation imposed by the French colonial administration on people living in cities. When he showed up at a studio in Bobo Dioulasso, he was stunned by the photographer’s fee and realised that there was good money to be made with a camera. His cousin, an influential man, took him back to the studio with a very much larger sum – ten times what he’d paid for his ID photo – and a bottle of Scotch. Negotiations went well, the bottle was drained, and for the next three years Sory worked with the Ghanaian Kojo Adomako. ID photos were Adomako’s stock-in-trade, produced to bureaucratic spec as head and shoulder shots. But he also offered ‘souvenir’ portraits, which would turn out to be Sory’s forte. In his archive there are many striking portraits of young people – singles, couples, siblings, girly covens, boyish gangs – who know how they’d like to appear to their friends and relatives; above all it seems, to themselves. In Sory’s view, they rarely posed for posterity. ‘No one ever came back to ask me to reprint a picture,’ he told Matthew Witkovsky, who curated the show in Chicago earlier this year. ‘They don’t need it, and they don’t care.’

This makes sense. Almost no proud male elders or imposing matriarchs can be found in Sory’s work. He sold his services to younger people, whose confidence had soared after independence, as Haute Volta acquired a seat at the UN. With this political joie de vivre came a range of careful self-positionings, an ostentatious show of youthful cool, and a sense that the speed at which European fashions were moving would leave you in the dust if you couldn’t master the force of Northern consumer culture. Exoticism is often thrown into reverse in Sory’s photos: his subjects pose in European mode, but knowingly, as if they didn’t really mean it when they slipped into a bikini or stuck an ear against a Bakelite phone, just as colonial Europeans in older photos stand over a kill as if they’d brought down a gazelle with an assegai.

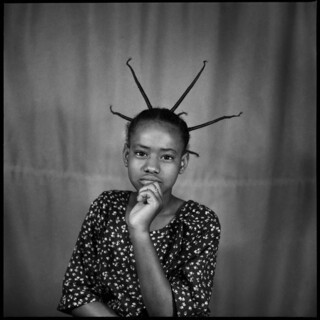

Just as often, Sory’s studio customers come straight to the point: they have paid to give it their best shot and strike the pose of their choice without disingenuousness or the unease we sense in the colonial subject sitting for the colonial record. La Jeune Malienne is typical, and the open-heartedness of her portrait tells us how little the ‘souvenir’ shot resembles the ID photo. Yet the ID photo remains a template for many of Sory’s compositions and raises large questions about the re-arrangement of ‘native’ identity under colonialism. Crucially, for the sociologist Jean-Bernard Ouédraogo, European rule effected a steady shift away from communitarian identifications – with the family, the village or an ethnic/linguistic group – towards that great modern instance, the individual. And, as Witkovsky argues in Volta Photo (Steidl, £35), ‘the replacement of group identification with individuated identity found its most adequate expression in the … ID photo that colonial administrations required in Bobo [Dioulasso] and across Africa. To have one’s identity specified and recorded, not only as an ethnographic type but as a juridical subject marked a rite of initiation into modern society.’ In fact we find quite a few of Sory’s customers sitting for group portraits as ‘family’. Others appear in traditional or ritual dress, but this isn’t strictly a contradiction: in the years that followed independence, Africans could have it all, laying claim both to an open-ended cosmopolitanism – encompassing the ‘free world’ and the Soviet bloc – and an African specificity that reimagined the precolonial past and stressed the importance of indigenous cultures. It was a great moment.

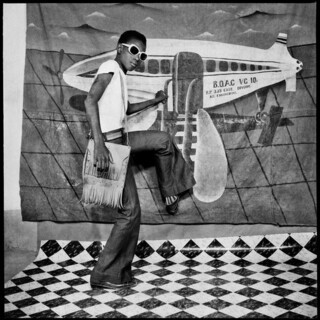

Sory wasn’t born in Bobo Dioulasso; he made his way to town from a remote village. Ouédraogo, who based his research on interviews with dozens of African photographers, found that only a very small number grew up in cities. Most took part in the steady movement from the countryside to a new urban life ‘severed from the old social order’. It was the cities that conferred a rudimentary civic status on their inhabitants in the eyes of the French: no one living in rural areas was required to register for an ID card, but anyone moving to an urban area had to have a bureaucratic profile. Sory’s souvenir photos prolong the story of identity beyond the colonial era into a moment of exuberance and self-definition, in which his customers play at being who they really are, or who they might be, as individuals in a new society where modernity is an asset rather than a reminder of domination. Like many studio photographers, Sory created sets for these self-performances by wheeling in props – motor scooters, mainly – and commissioning backdrops. The best and calmest of these is an urban scene, almost a village corner, with Sory’s studio, Volta Photo, taking pride of place. A beach scene with palm trees and high-rise hotels was popular with many of his customers; for more dashing poseurs, there was a VC10 on a paved apron, aircraft steps alongside, ready for boarding: you needed elegant shades and wide flares to carry this off.

Sory was less of an interventionist – less of a director – in the studio than an older generation of African photographers led by Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keïta.* Even his demure sitters are shot with a kind of nonchalance and matter-of-factness. What he liked, mainly, was the freedom that having a camera gave him – his first was a ‘Shanghai’, a twin lens reflex made in China – and the income it brought in. (One of Ouédraogo’s photographers told him that a single evening’s work earned him half what he made in a month as an office clerk.) While it’s true that Sory’s photos show a society undergoing immense change, it’s the photographer himself, the man with a camera, who embodies the forces driving it along: available technology, business acumen, faith in an African cutting edge and a willingness to depict people in the way they wish to be seen, as autonomous selves in an independent country.

Sory’s easy-going style helped with his work at parties. People who had organised their own event with their own music generally beat a path to Volta Photo. They would appear out of nowhere, he told Witkovsky, and say: ‘Sory, we’re dancing tonight. We’re going to celebrate, there’s food, we’re getting a sheep, some chicken …’ He would take charge of the photographic record for a fee. It wasn’t long before he began organising dance events himself, mainly outside Bobo Dioulasso. He would arrive at a prospective venue, announce a date, collate the music, emcee the event and, of course, take the photos. Moving around rural areas after harvest proved worthwhile. ‘Rice, bananas, especially cotton,’ he told Witkovsky. ‘If cotton is selling – ooh! – farmers have money.’ At these outdoor parties, or bals poussières – the dancers kicked up a lot of dust – people who wanted their photos taken notified him in advance, paying upfront for the film and ordering a set number of prints, sometimes by the roll. The photos that survive are mixed, often so informal that they might have been taken by a village amateur.

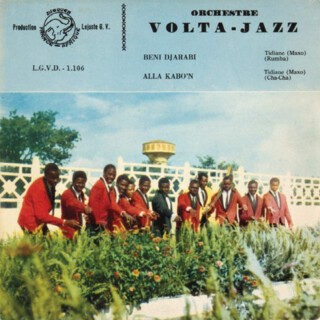

Sometime in the late 1960s Sory began taking photographs for record covers for Volta Jazz, a band founded by his cousin – the same cousin who had helped him to clinch his apprenticeship with a libation of Scotch. Bobo Dioulasso had a strong tradition of popular music in a range of styles, largely thanks to the enthusiasms of a local youth club, active in the 1930s, the Société amicale de la jeunesse dorée. But recording studios, according to Sory’s archivist Florent Mazzoleni, were in short supply. Volta Jazz made its name on the dinner-dance circuit, at Rotary Club events, concerts and dance halls. The band dressed in tuxedos and – as far as you can tell from web audio – had a virtuoso mastery of styles, including local Mandingo and Afro-Cuban, which had percolated up from Central Africa. This was not a dilettante outfit. When Volta Jazz found a way around the recording problem, the artwork was assigned to Sory: his photos appear on the covers of at least a dozen singles by the band.

In the global North, the work of African studio photographers has enjoyed a vogue since the 1990s. It is one of the few sub-Saharan sites of exploration where valuable discoveries may still come to light. For European and North American curators, and their African protégés, the rewards are handsome. Sanlé Sory has turned out well in every sense. He reassures us that we can ascribe works in Africa to individuals, whether they’re photographers, musicians, choreographers, visual artists, practitioners of oral literature (sung verse and narrative) or vernacular architects: the old imperial scholarship, in which ‘African’ arts were a generic subdivision of ethnography, is behind us. But the clock is running down on the glamour of the authored offer – and not just in Africa. Everything we consume, from the undistinguished novel to the remedy for back trouble, comes with a proprietary name, or a brand; the competition for renown was never harder. This is Sanlé Sory’s moment, and he’s made the most of it.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.