In January 1939, an itinerant Angolan sent a postcard from the Belgian Congo to a friend back home. ‘Salute my wife,’ he wrote. ‘Tell her that her old husband still has not lost the fire of his youth. He faces thundering rain and hunger, but he goes by canoe, carrying loads as if he were a boy of 18.’ Antoine Freitas was approaching 40 when he wrote the card; the loads he mentions were the cumbersome clobber of a journeyman photographer. He’d learned his craft from a missionary in Angola and built his own box camera. He was travelling from region to region – ethnic group to ethnic group – earning a living by taking photographs of people. The image on the other side of the postcard was of Freitas in Kasai Province, taking a portrait of five women, surrounded by a crowd of onlookers.* It’s an action shot by a colleague, and a rare glimpse of an African photographer going about his work.

Freitas was not, as far as we know, a civil servant involved in a colonial recording venture. He was paid by families and communities who thought the thing to do was to have their portraits taken. When he was making the rounds in the Congo, there were only a few people like him, and many more like them. By the mid-1940s, as small studios began to proliferate in African cities, the customer was coming to the provider, and photographers no longer needed to be as intrepid as they had been. St Louis, the old French colonial capital at the mouth of the Senegal river, was a studio hub of sorts, first for wealthier African families and, as time went on, for people of modest means.

In the 1990s, as scholars pieced together a history of African photography, the CV of a typical pioneer began to look roughly as follows: an early obsession with photographic images, a wish to be the magus with the box, help from a European photographer, acquisition of an Eastman Kodak camera, sometimes military service, and then, more often than not, work for the state bureaucracy, producing ID photos in the wake of independence. A body of post-colonial scholarship now lies coiled around this rich and fascinating subject, yet the career paths of successful studio photographers in Africa weren’t all that different from those of their counterparts in Europe, even a figure like Edward Chambré Hardman, whose father enjoyed photography and whose real passion – for landscape and cityscape – lay beyond the portraits he took in Liverpool in the 1940s and 1950s. (Hardman was still taking portraits for a living after his photograph of the Ark Royal in the Cammell Laird shipyard made his name.)

The Malian studio photographer, Seydou Keïta, whose photographs are on show at the Grand Palais in Paris (until 11 July), was apprenticed to a joiner in Bamako in 1928 at the age of seven or eight and later experimented with a Kodak Brownie which belonged to his uncle. A Frenchman working at a local processing lab gave him a technical steer and by the end of the 1930s he was making good money from portraits; visiting clients in their homes or snapping up commissions on the street. The turning point for Keïta, one of the great studio hands on the continent, came at the end of World War Two, when another photographer, Mountaga Dembélé, returned to Mali after serving with the colonial infantry in Europe. Dembélé set up a studio in Bamako and began training enthusiasts. He was a few years older than Keïta and is said to have been a great photographer, though only a fraction of his work survives. From Dembélé, Keïta learned to develop a good contact print, 13 x 18 cm, which, after he opened his own studio in 1948, was the staple product supplied to the customer. Keïta ran the business at full tilt until a year or so after independence in 1960, when he was asked – or probably told – to work for the new government. He kept the studio ticking over while he photographed state events, visits by foreign dignitaries, military grandees, official openings and so on. He also worked for the police, though we don’t know what he did. Forensics? Mugshots? Driving permits? In 1977, he shut the studio and returned to another of his loves: tinkering with cars and scooters. He was a good mechanic.

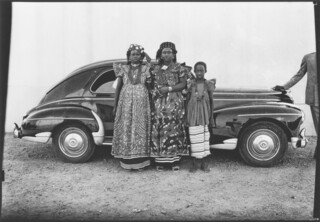

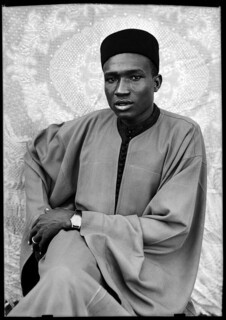

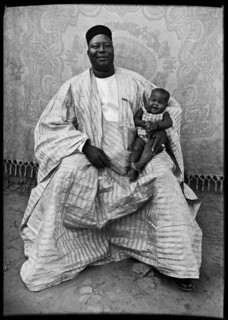

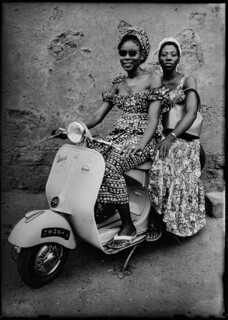

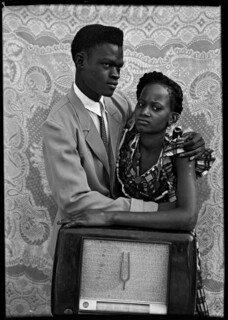

Keïta took at least 10,000 portraits; about 300 are on show in Paris. Some of his sitters are photographed full-face, others at an angle. ‘Le portrait en buste de biais,’ he said of his three-quarter, head-and-shoulder compositions, ‘c’est moi qui l’ai inventé.’ It’s quite audacious. So is the idea, which we encounter in the catalogue essays, that the angled shot marks a break with colonial photography, releasing the subject from the chilly condescension of the full-face shot. If so, it was an uneven, staggered break: both types of composition can be found during and after the colonial era. Yet Keïta’s work is remarkable for its lack of intrusiveness. Subjects may be on their mettle, in complicated ways, but they aren’t up for examination, or sitting for an ethnographic inventory. The customers led the way. They were paying for a record, in a single, dignified image, of what they imagined themselves or their dependants to be: who they were, their standing in the world, and who they might become; their sense of continuity (a beaming notable dandles a child on his knee) and their intimation of a new order (two young women sit astride a scooter) in a moment of dramatic change for the country. Often – as in the image of a woman resting her head on her hands – it’s a combination of the two. Even where sitters prefer a formal, sober attitude, holding themselves a little stiffly as they might for a colonial photograph, their composure is more adornment than disguise: people are entirely, uncannily present, throughout the work – a presence that Malick Sidibé, another famous studio photographer in Bamako, rarely achieved. Many of Keïta’s sitters have a monumental ease, negotiated with the photographer.

The portraits are staged, to the point of theatricality. Keïta set up his studio in a compound near the railway station (also not far from the prison). His backdrops – a plain drape at first, and later batik fabrics (leafy arabesques and cloudy paisley) – could be pinned to an outer wall or moved indoors but he preferred to do portraits in natural light, and many, as the exhibition catalogue suggests, have a plein air quality. He kitted out the studio with a stock of props and costumes, from which he and his sitters could choose whatever they thought would strike the right aspirational note: two-piece suits, ties, hats, wristwatches, jewellery, fountain pens, a radio, his Vespa. He even placed customers in front of his Peugeot 203 (you can see his reflection in the front fender). Each photograph in this marvellous oeuvre is evidence of Keïta’s wish to bring out the best in his sitters. ‘Having your photo taken was a big event,’ he recalled. He approached his commissions like works for the stage or tableaux vivants. One performance only though: Keïta almost always relied on a single exposure to do the trick. ‘I never got it wrong,’ he said later.

Keïta was ‘discovered’ in the 1990s, when Mali’s musicians and singers were already surging onto the world music scene: Salif Keïta, Fanta Damba, Alpha Yaya Diallo, generous sprinklings of Diabatés, Tourés and Sissokos; a glorious moment. The French impresarios who introduced Keïta to the world revisited his archive of negatives, sent them off to labs in Europe and commissioned gigantic prints. They were a sensation when they were shown in France in 1994; ten years later in New York they were selling at $16,000 a throw. They are darkroom miracles by comparison with Keïta’s own prints, about forty of which are on display in Paris. The light in Mali was his loyal assistant: despite five or tenfold enlargements most of the new images are crystal-clear. They bring us face to face with a luminous beauty that we can’t get from the original contact prints.

They are also controversial. There have been disputes about money and royalties, just as there were between Malian musicians and the world-music labels that signed them up. The larger objection is based on creaky notions of authenticity, originality, and whether or not Keïta should be elevated to the rank of ‘artist’. He died in Paris 15 years ago thinking he should: he loved the new prints. The idea that the earlier ones have a sacred authenticity, like primitive paintings, and that they’re travestied by later reproductions, is pure exoticism: it wants Keïta and his subjects stranded in the middle of the last century, embalmed in Africanist nostalgia. Anyone who owns a print from the Bamako studio must of course be making the case for an intriguing, weather-beaten relic and hoping to raise the value of their asset on the back of five-figure sales for a single enlargement. But the enlargements bring Keïta and his subjects into the present: we are bang up against them in the new 180 x 120 cm prints. They are also conclusive evidence of Keïta’s mastery, and lose none of the mood of the period: a time of hope, as Malians looked forward to independence, enjoyed the trappings of modernity, and revelled in a sense of their own traditions.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.