The Biltmore Hotel in Coral Gables, Florida is enormous. So is its pool, which you could say is more of a lake. When Madonna stayed there in the early 1990s, she apparently insisted on having the pool to herself, less for the swimming perhaps, and more because as a material goddess she could. I went to a book party at the hotel years ago (the American Booksellers Association jamboree was in nearby Miami’s South Beach that year). Will Self and his American publisher, Morgan Entrekin, arrived as I was leaving. The vast expanse of water and the huge hotel behind it made Self momentarily speechless. ‘Belly of an architect,’ he said, using the title of the Peter Greenaway movie to express his amazement.

‘A pool is water, made available and useful, and is, as such, infinitely soothing to the Western eye,’ Joan Didion said. She was writing about California, where pools, in her view, were less a symbol of affluence than of order – ‘control over the uncontrollable’. The history of California is to a considerable extent about the mastery of water in desert conditions. Pools are soothing – except when they aren’t. There’s nothing relaxing about a public pool in London when speed swimmers go about their hectic training. If you’re not a racing swimmer, speed in a pool seems pointless: what’s the rush, where are you going?

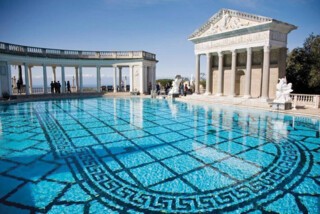

Pools have aesthetics. Most large pools are rectangular and blue; the science of light makes large volumes of water appear blue, and blue tiles enhance this. Public pools often have lanes marked out by darker tiles, implying that swimming should be straight. Hotel and private pools don’t have to follow the rules. There is a pink pool in Sag Harbour on Long Island – you can see it from a plane window as you approach JFK. Some pools are more obviously symbols of affluence than others. Randolph Hearst’s Neptune pool at San Simeon may be the most opulent pool ever constructed, with its elaborately tiled floor and surrounding statues, colonnades and classical façades.

The second most opulent pool may be the indoor ‘Roman’ pool Hearst built at his Californian palace, which is filled with water pumped up from the Pacific. Charles Sprawson describes it in his history of swimming, Haunts of the Black Masseur: The Swimmer as Hero:

The brilliant dark blue tiles studded with gold stars create the illusion of vast and mysterious depths and transform the interior at night into an underwater grotto. It was there that Hearst preferred to swim, lap after lap alone … among the shadows of statues cast on its surface by the dim light of alabaster lamps that quivered in the indigo water pumped from the sea seven miles away.

Romans knew about lavish baths: Hearst seemed to be trying to pick up where the emperors left off – only they often chose to make baths for the people, not just their friends. The outdoor public pool at London Fields, where I go swimming, has no lapis lazuli tiles, but the heated water in midwinter feels undeniably luxurious. I’m short-sighted enough for the other end of the fifty-metre pool to be beyond my field of vision, and I don’t have to swim far out to sea to lose sight of the coast. It’s a good feeling: swimming has always seemed to me more of a mood than a sport.

Haunts of the Black Masseur is an unforgettable book. The first edition, published by Cape in 1992 and reviewed in the LRB by John Bayley (23 July 1992), was handsome; on its front cover is a photo by Leni Riefenstahl of a diver holding a swallow pose, her head about to plunge through the surface of the water. The pictures inside include one by Lartigue of a swimmer sitting on the sand at Houlgate beach: she’s propping herself up with her hands and appears exhausted by her swim in the Channel that sunny day in 1919. The reissue (Vintage, £8.99) of Sprawson’s book has no illustrations except for a generic picture of a swimmer in blue water on its cover. A line on the back cover suggests readers might also like Joseph Mitchell’s collected New York journalism, Up in the Old Hotel, but who knows why?

Iris Murdoch was a Sprawson enthusiast. In her review of the book, published in the New York Review, she revealed her own aquatic inclinations:

I am not in the athletic sense a keen swimmer, but I am a devoted one. On hot days in the Oxford summer my husband and I usually manage to slip into the Thames a mile or two above Oxford, where the hay in the water meadows is still owned and cut on the medieval strip system. The art is to draw no attention to oneself but to cruise quietly by the reeds like a water rat.

A natural affinity for water was the way one Olympian explained the fact that some people are better at swimming than others, and that applies equally to a novelist who saw as herself as a water rat.

Two hundred years ago, swimming in rivers and lakes was very much more common than it is now. Swimming naked, too – costumes and trunks were a Victorian contribution. The English were said to be the best swimmers in the world. Contests were held on rivers, diving off bridges was familiar, and Byron swam miles down the Thames with the tide. He wasn’t afraid to boast of his exploits: asked what he could do that other people couldn’t, he said he had four answers: ‘I could swim for four miles – write a book, of which four thousand copies should be sold in a day – drink four bottles of wine – and I forget what the fourth was, but it is not worth mentioning.’ Floating pools were moored at Waterloo. All of which may make you wonder why swimming, and the baths, disappeared for so long after the fall of Rome. The answer, according to Sprawson, was Christianity.

Haunts of the Black Masseur is a striking title derived from Tennessee Williams. Williams was a swimmer, and Sprawson made a point of swimming in many of the places with which Williams was familiar: the Hollywood Roosevelt, off Santa Monica; the Venice Lido; the beach at Barcelona; the abandoned pool at Williams’s house on Key West. Williams was buried at sea, as he’d wanted, his body dropped into the Gulf of Mexico where Hart Crane fell overboard and drowned. ‘I’ve always admired the gentleman,’ Williams said, ‘and I never had the opportunity to meet him.’

The pool at the New Orleans Athletic Club was another of Williams’s haunts: ‘Desire and the Black Masseur’ was originally the title of a short story based on a tale he heard there. The exquisite first sentence is ominous: ‘From his very beginning this person, Anthony Burns, had betrayed an instinct for being included in things that swallowed him up.’ Burns is a clerk who gives in to the raptures he experiences when he’s in the hands of one of the club’s masseurs and goes there again and again until his bones begin to break. Burns and the masseur are discovered. They are thrown out. But devoured by desire Burns can’t keep away, and the masseur breaks more and more of his bones until there’s nothing left to do but to eat him. After his swim at the New Orleans Athletic Club, Charles Sprawson always made sure to have a massage.

I began to swim regularly less as a way to fulfil a desire than to stop another. This was the way I escaped from the shadow of a smoking habit. The unpleasant months of physical withdrawal had passed, I no longer wanted to smoke, but 18 months after I stopped I developed acute pins and needles that only water assuaged. Baths, pools, rivers, sea. The pool at Parliament Hill wasn’t far away. At opening time, there was already quite a queue; the same man was always first to go through the turnstile. I used to swim eight hundred metres in the unheated pool, but as autumn turned to winter and the temperature fell below 13°C, I moved on to the pool at London Fields. Staying in the pool was more important than the wish to get out of the cold.

I wasn’t allowed to forget that I wasn’t hardy enough for the pool at Parliament Hill. On days when I was at the British Library, a white-haired man occasionally tapped me on the shoulder in one of the reading rooms. He only ever had one word to say, and the word was always a number. Seven, five, five, seven, six, eight. He was telling me the temperature of the water at Parliament Hill. The water at London Fields is a Mediterranean summer 25°C year-round. Nine, ten, eight, eight, nine, the white-haired man said, as the water temperature rose with the end of winter. Only once was he more expansive: ‘Eight,’ he said. ‘A very cold eight.’ A non-swimmer might not know that eight isn’t always eight.

Poseidonia, a city named after the god of the sea, was an ancient entrepôt a hundred miles south of what is now Naples, where the Greeks traded with the Etruscans. Paestum is the name of what remains of the town. The columns of three temples survive and so does the painting of a tanned, naked man who has leaped from a stone platform and is diving head-first, his arms outstretched. The figure exudes supreme confidence – he is said to be diving into the Sea of Eternity, though the water looks very shallow. At the end of Haunts of the Black Masseur, Sprawson recounts his swimming and diving in pools at Gafsa, a town in Tunisia with a history even more ancient than Paestum’s. A young man kept encouraging Sprawson to dive into a pool from ever greater heights, until Sprawson balked at the idea of diving from the top of a palm tree into just three feet of water. But maybe like the ancient diver at Paestum, that young man knew exactly what he was doing, and could find eternity in three feet of water.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.