It is a perfect Impressionist scene: a strangely empty stretch of the Seine, at the crossing-point between Suresnes and the Bois de Boulogne, where Parisians imagined themselves in the country. The view is from one side of the river, cropped so that the prow of a boat and the prongs of a tree intrude from the left; reflections seep and blur across its surface, like colours mixed into the water. A restaurant on the bank advertises itself in block print: ‘friture, vins, café, bière’. A factory chimney is aligned directly behind one of the Suresnes bridge’s towers, so that it appears to be part of the same structure: a witty optical illusion, of the kind we’ve learned to look out for and appreciate. But this isn’t a painting. It’s a photograph taken in 1870, a document of the Franco-Prussian War. Look again and you notice that the bridge itself is missing, destroyed by the conquering Prussian army; its suspension cables dangle in the air.

The men who might have made this picture had different priorities. Earlier in the year, Frédéric Bazille had produced a painting of the studio he shared with Renoir on the rue de la Condamine: in it Manet and Monet are shown examining one of Bazille’s pictures; Zola is on the stairs, leaning over the bannister to chat to Renoir. Bazille’s canvases and one of Renoir’s hang on the walls, all of them rejected by the Salon; the pianist Edmond Maître is playing under one of Monet’s still lifes. Bazille’s lanky figure, almost the height of the canvas he is showing his friends, was painted in by Manet; beyond him, a half-curtained window gives onto a view of the boulevards. The painting is a record of friendship, of shared endeavour, mutualised self-belief. A few months later Bazille, who had enlisted as a Zouave when the war began, was killed in one of the several futile battles fought in the hope of breaking the Paris siege. He was 28. Renoir was conscripted and sent to the Pyrenees, where he got dysentery and nearly died. Monet, who had done a tour in the army in the early 1860s, was called up, but absconded to England. Zola stayed in Paris (he later wrote The Debacle, a novel of the war and its aftermath, partly based on his experiences), as did Manet, who with Degas enrolled as a gunner, serving under the classicist and Salon favourite Meissonier. (Berthe Morisot sent out her letters by hot-air balloon.) As the enemy approached, Cézanne scarpered to the countryside, as did Alfred Sisley, whose home in Bougival was wrecked, along with the majority of his canvases (his family’s export business was also fatally disrupted, leaving him out of pocket for the rest of his life). Pissarro left behind almost his entire life’s work at his house in Louveciennes, which the arriving Prussians promptly turned into a stables: all of it was lost. Courbet, launched into authority by the whirlwind of the Commune, ordered that the Vendôme column be toppled, and brought his career down with it (he was later imprisoned, and then forced to leave France).

The show at the Tate opens with a room devoted to images of the war and the Commune. Corot’s Dream: Paris Burning, painted urgently on the morning of 10 September 1870 after a nightmare about the Prussian advance, exhibits none of his usual graces. Sickly blue smoke lifts off a morass of broken brushstrokes in grey, red, brown, orange: the city itself, collapsed, unknowable. A defiant Marianne, in skirts of smoke, arm aloft, is scratched against a turbid sky; a vaporous angel of death is fleeing the frame on the right. There are no such illusions – another surprise – in James Tissot’s small, brutal watercolour of an event he witnessed on 29 May 1871. It shows a high wall, part of the fortifications in the Bois de Boulogne, and a man in the uniform of the National Guard plummeting backwards through the air, jacket gulping, hands feebly gripping, his head bent towards the ground, where 13 broken bodies already lie, bloody, heaped, their heads at odd angles. Two sprays of blood graffiti the bricks. There is something eerie about the picture’s economy. We can’t see the top of the wall, only the falling man, and our view of the ground is tightly restricted; the eye fails to escape through a gap on the right, blocked with more of the same muddy green. These men were Communards, shot and dumped over the wall at a time of terrible retribution which saw the French army, tasked with reclaiming Paris, execute as many as 25,000 of their fellow citizens.

Two lithographs by Manet depict similar scenes. In Civil War a National Guardsman is stretched out dead in front of a half-demolished barricade made of paving stones; it is hardly possible to look at his neatly out-turned feet without thinking of the soldiers levelling their guns in The Execution of Maximilian, finished a few years before. The debt is transparent in The Barricade, which directly lifts the soldier group from The Execution, placed this time on the left, their target no longer a hapless Habsburg but an anonymous Communard backed up against another wall of cobbles: the sweep of his arm, magnificently and impossibly extended – he is bravely waving his hat – marks a separation between him and his killers, a sort of rupture that Manet created by leaving the space between them blank, perhaps to indicate rifle smoke, or simply to convey the flash of violence, its sudden shrinking of the world to significant detail. Either way, it is a measurable moral distance. One of the striking things about both drawings is the jarring evidence of ordinary city life crowding these unordinary deaths: the dainty railings beyond the barricade in Civil War, the lampposts and chimneys in the background of The Barricade. Also in the room are photographs of Paris, brutalised by the siege and the mass burnings of the disintegrating Commune, then aestheticised as a capital of ruins. A picture of the Ministry of Finance, taken by Charles Soulier in May 1871, shows an archway bulging with shattered bricks that spill into the street, the upper windows framing clear sky; on the wall, a handbill advertising a concert has had its centre ripped out, as though punctured by a bomb.

At this point the show permanently switches its focus, rewinding to 1870 and the mass migration of artists across the Channel. Britain was the traditional resort of the French exile and those fleeing the collapse of the Second Empire joined an earlier community of political refusés now gearing themselves for a return, a group that included members of France’s two rival royal families, rightly sensing an appetite for a restoration. London, the largest city on earth, was a perfect place to lie low. (And to make money: its art market was booming.) But it wasn’t easygoing. ‘It is a kind of humiliation in a great city not to know where you are going,’ Henry James observed, and this was more than usually the case when the great city was dense with fog, as this one was in the winter months. To a friend considering the move, Daubigny counselled: ‘bring some food … I have to stop writing my letter to you to light a candle: it is 11 a.m. Say no more about the climate.’ Nonetheless, networks quickly established themselves. Monet stumbled across Daubigny painting by the Thames, who put him in touch with Paul Durand-Ruel, that ‘Napoleon of dealers’, who had led a troop of 35 crates onto foreign soil and opened a gallery on New Bond Street; Durand-Ruel told Monet where he could find Pissarro, who was staying in Norwood with his mother and brother-in-law. Alphonse Legros, a French painter who had moved to England in 1863 and now taught in South Kensington, was an important point of contact for nearly everyone. The community congregated in cafés in Soho, including Maison Bertaux, set up by a Communard and still going on Greek Street, and visited the galleries. They also, of course, worked.

If it limited itself to showing the art created by these exiles in the early 1870s, this show would be a great deal smaller: most of those who came over were back in France within a year or two, once order had been restored. The curators’ decision to push on into the 20th century is understandable, though it stretches the organising concept way past breaking point: all the works after 1879 (when an amnesty for Communards was proclaimed), but also many of those done earlier, are by artists on holiday, or on commission, not ‘exiles’ in any meaningful sense. The show doesn’t purport, or attempt, to document the evolution of French or British artistic trends or tastes – what is on view is too partial and self-selective for that. Nor does it distinguish usefully between working in London and working on London as a subject, or ask what doing either meant at any particular moment. But, by sprinkling some of the Impressionists in among lesser-knowns, it at least reminds us to see them as they were seen, and as they saw themselves: as running largely counter to, but nonetheless in parallel with other approaches and initiatives (it is somehow surprising to find Pissarro approving Watts and Rossetti as ‘modern men’). The show is unable to decide whether it is doing social history or doing ‘good art’ – the catalogue plumps for the former – and it doesn’t succeed in doing either, all of the time. But it can’t help being interesting.

On their first visit to London – they both arrived in 1870, in September and December respectively, and were gone by mid-1871 – Monet, who lodged off Shaftesbury Avenue, and Pissarro, who stuck to Norwood, were only moderately busy. In the second room is Monet’s The Thames below Westminster, already sensitive to London’s atmospherics: the sun is suppressed by fog, tinted yellow, rendering unsteady the outline of the just completed Palace of Westminster. In the foreground two men are taking down scaffolding set up against the Victoria Embankment, also just completed. It is a new view, newly iconic, but still, just, provisional. Elsewhere, there is Hyde Park, painted by Monet with his back to the Serpentine, the rooftops of Bayswater Road forming the horizon. Groups are scattered over the grass, which is bright green in near-focus, muted further out, where the fog is again in evidence: a powder blue is unexpectedly worked in among the trees, creeping up the wavering spires of the nearby churches (‘high things’ in London, James wrote, ‘take such an effective blue-grey tint’). Pissarro’s output from this time is more familiar, though as appealing as ever: from the National Gallery come the sunny afternoon strollers in The Avenue, Sydenham and the wintry Fox Hill, Upper Norwood; Lordship Lane Station, Dulwich chugs in from the Courtauld. In the less familiar Crystal Palace, the eponymous building is relegated to the far corner, its ‘hard modern twinkle’ (James again) slurred by rolls of grey paint, subdued beneath a water tower; our eyes are drawn instead to the wide open curve of a sloping sunlit road, and to the brilliant stub of red on a child’s hat, reflected back by the cloak of a woman walking arm-in-arm with a gentleman on the right, repeated by the chimneys of the houses stacked up at the bottom. But then we examine more closely the walking couple, observing the position of the man’s legs, the extension of his arm, and realise they are not walking at all, but have stopped and turned to admire the palace. We are in classic Impressionist territory: the spectacle is the spectacle, the spectacle is the city vivant, and we look at people looking. Of course, the painting didn’t sell, though Durand-Ruel did take Fox Hill; Monet had worse luck. Both men’s submissions to the Royal Academy were rejected. ‘There was no art,’ Pissarro glumly remembered.

There was Tissot, however, who landed in England shortly after painting that watercolour in May 1871 and stayed until 1882, enjoying splendid success. A room and more is turned over to his particular variety of Victorian kitsch. A friend of Degas and Manet, Tissot chose similar subjects – garden parties, balls, women of dubious reputation – but forced them into a British manner more reminiscent of Millais, whom he admired, but without his talent and flair for drama. What they do have is a thoroughly un-British, Second Empire naughtiness: in The Ball on Shipboard a sailor ogles a lady’s backside as he follows her up onto the top deck; in Holyday, the archaic spelling itself a joke, a man lounges between two women on a picnic rug, a drawer’s worth of knives pointing at his crotch, while two couples flirt in the background, screened off from an old woman who is anyway dozing over her tea. Jean-Baptiste Carpeaux, the sculptor of the Second Empire, who had scandalised Paris with his grinning nude dancers at the new opera house, was also in London. He was now left with the task of memorialising Napoleon III, whose St Helena turned out to be Chislehurst. The bust he made from sittings there and from subsequent sketches at Louis-Napoléon’s deathbed (in 1873) shows the deposed emperor in melancholy reflection; his lapping, tongue-like beard, faintly obscene, hides the soft falling away of his chin.

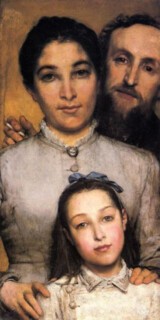

Carpeaux’s pupil Jules Dalou, a known Communard, lived in London from 1871 to 1879, and with a sort of perverse logic went on to become the sculptor of the Third Republic. While in Britain he received a host of aristocratic commissions, as well as one from Queen Victoria, at the price of submitting to the sentimentality of British taste. Still, his astonishing skill elevates even quite unpromising subjects: a French peasant breastfeeding her baby, done in terracotta, is a wonder. One of the most charming things in the exhibition is not by Dalou but rather of him: an intimate family portrait by his friend Lawrence Alma-Tadema, another refugee from Paris, whose own stay in Britain turned out to be permanent. In it Dalou smiles over his wife’s shoulder, a lit cigarette trailing in his hand; she in turn rests her hands on the shoulders of their young daughter. It has the quality of a snapshot, as if Dalou had wandered over from his studio and leaned in at the last moment. It has something of exile in it also, of the family as the last unit of resistance. Sisley, as always seems his fate, flits in and out of the exhibition: he spent time in London in 1874, his trip funded by the legendary baritone Jean-Baptiste Faure.

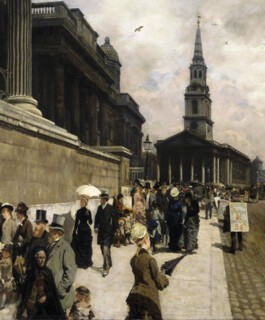

One of the genuine surprises is Giuseppe de Nittis, an Italian included in the curators’ flexible remit on the grounds that he lived in Paris and made annual trips to London from the mid-1870s, producing a series of 12 views for a Lancashire coal magnate. It was his habit to develop his scenes from sketches made in the back of a cab – that ‘vehicle of vantage’ (James yet again) – so they are characterised not only by a slightly dizzying, elevated perspective, but also by a definite sense of motion. In The National Gallery, the gallery itself is pushed to the shadowy, sooty margins: the focus is on the road in front. There is social variety to match William Frith, but none of his static staginess. Instead, we loom over the shoulder of a young woman, facing the stream; beggars, chatting couples of both sexes, women with children, a soldier signalling in bold red, walk towards us. A gent close to the kerb is ducking round an incoming umbrella; men wearing sandwich boards advertise a café; there’s a muddle of carriages towards Charing Cross. Piccadilly: Wintry Walk is just as dynamic, the subject again a busy road, with at least six identifiable lanes of traffic, a woman and her daughter darting hopefully across; anthills of heads swaying on the tops of far-off omnibuses. Swift strokes of paint, elongated in the wake of one cab, curving after another, convey the grime and glitter of the wet, sped-over road. The whitish, spreading sky – the trees lining the boundary of Green Park seem almost to dissolve in it – has a tense luminosity.

In the same room is Westminster (1878), De Nittis’s most spectacular attempt to capture the peculiar intensities of London light: a vast, doomy canvas constituted almost entirely of shades of ochre, red and black (it immediately put me in mind of the latest Blade Runner). We are situated on Westminster Bridge, the perspective skewed so that the foreground is squeezed to the right; a gang of workmen lean against the railing, enjoying an early evening smoke and the view. The Thames is satiny, its reflections softened and smoothed out; the Palace of Westminster, backlit, is all shadow, all outline. Small relief from the dominant hues is offered by a puff cloud of white around the men’s heads, which initially appears to be the product of their pipes, but of course is the fog, spilling over the parapet.

De Nittis, who has fair claim to be considered an Impressionist – for one thing, he exhibited at their first collective show in 1874 – anticipates in these pictures the work of Monet and Pissarro, both of whom made separate returns to London around the turn of the century. Most obviously, with Westminster, De Nittis prefigured Monet’s studies of the Houses of Parliament, twenty of which were made between 1903 and 1904, painted from a room in St Thomas’s Hospital on the opposite bank of the river. Six of these are in the exhibition, clearly intended to provide its grand finale, as they have the copy for the posters on the Tube (the critics have cooed). Monet had belatedly become fascinated by London’s ‘black, brown, yellow, green, purple fogs’: ‘the interest in painting is to get the objects as seen through all these fogs.’ His method was to slather on paint in vertical strokes, modulating the colours, letting the brush run on and blur; in every image Parliament is a featureless, fading outline, but, depending on the light, sea-green, indigo, near black, purple. The river absorbs and extends the shades of the sky, flattening the plane. Up close the pictures are bleary, muddy, but at a distance the quantity of paint conjures the fog as a medium through which the building fights to be seen. The impression, though, is always of a mirage – of a palace floating in the sky. The element predominates; the atmospheric has become stratospheric.

The real triumphs in this show are Pissarro’s late works, done great disservice by being presented as the warm-up act. ‘Pissarro’s importance has not yet been properly understood,’ Sickert wrote in 1911, clearly a century too early: ‘Writers on art have insisted so exclusively on that side of Impressionism which dealt in series of studies of different effects on one subject under different illuminations, that the whole gospel of Impressionism was supposed to be limited thereto.’ When Pissarro returned to London in 1891-92, he had passed through his excitable pointillist phase, though his methods had been permanently changed. He was also having trouble with his eyes, so that he took to painting scenes from the shelter of a window. Bank Holiday, Kew, consequently has something of De Nittis in its raised perspective (Pissarro had taken rooms above a bakery), as well as in the busyness of the scene: we see London en fête, a square crammed with people and conveyances, including an omnibus (the influence on Lowry is obvious). What is marvellous, however, is the vigour of the painting: the thronging figures are sketched with short fat strokes, and then revisited, given outlines and quirks in thicker paint – green dancing through a man’s jacket, stabs of yellow on the women’s hats. The massed group at the top right is constituted simply by small gobs of primary colour.

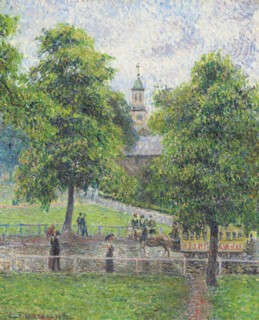

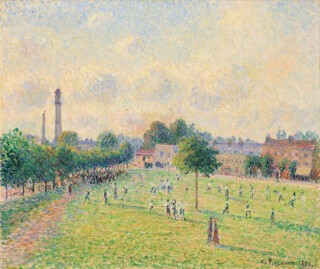

Not long after he painted this picture, Pissarro rented a different apartment in Kew, on Gloucester Terrace. One result is the extraordinary St Anne’s Church, his view from its west-facing window. It’s extraordinary not for its subject matter – a patch of garden, a road framed by two trees, one on either side, down which an omnibus is being pulled, beyond which rises the spire of the church – but for its technique. We know that there has just been a summer shower, not because of the umbrellas carried by passers-by, but because the road shimmers wetly in the revived light. The effect is achieved by hundreds of tiny strokes in an impossible range of colours: blue yellow green red purple white orange, at a glance. The trees sparkle after the rain: purple blue orange green red lilac. A wodge of yellow makes a mane for the horse pulling the bus; its collar is a swatch of blue, its harness a jolting streak of orange. Everywhere, the paint is laid on so thickly – seeming to boil up from the canvas – with such lavish, darting attention and in such dazzling diversity of colour, that it takes on an almost sculptural quality, working in relief: depth and contour are achieved without recourse to darks and the strategic use of shadow. In Kew Green, which depicts a cricket match, the effect is the same. An intense build-up of bright colour, massing, patterning, expressive in its swelling, roiling solidity, magically captures the effect of sunshine on the landscape, on the men in their whites, on the spectators under the trees, simultaneously blotting and highlighting, throwing them into different relation. This is Impressionism at full tilt, achieving its full effect: the world made tangible by ‘coloured vibrations’, to use Jules Laforgue’s phrase. ‘To study the work of Pissarro is to see that the best traditions were being quietly carried on by a man essentially painter and poet,’ Sickert concluded. ‘For the dark and light … of the past was substituted a new prismatic chiaroscuro.’

In another way too we should be celebrating Pissarro’s vision over Monet’s. His London was not the one retailed on postcards, then and now – it is instructive that his pictures of the Thames are relative failures, straining to accommodate its iconography. He did not fetishise the famous fog, nor did he admire it, like Monet, from rooms at the Savoy. When he visited in his later years, he did so in the summer months, and he stayed close to family. London was a home from home: by 1897 he had three sons living there. He had married their mother, Julie Vellay, at Croydon Register Office, shortly before returning to France in June 1871. There is all this, I think, in his pictures. If we are doomed to carry a version of Victorian London in our heads, why shouldn’t it be his? Stuff Westminster and the smoke.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.