Mr Zank was quite short, maybe five three with a wide waist for his size, somewhat wavy brown hair, about fifty, looked directly at you when he spoke with soft remnants of a Polish accent. He worked in the Garment Center, took the BMT subway into Manhattan every day and at weekends had a part-time job at a boardwalk hot dog spot two blocks from where we lived in the Brighton Beach section of Brooklyn. He lived with his wife and young son Robbie in the four-storey apartment building next door to our house. That building was a walk-up with three and four-room apartments. He was a committed and grateful American citizen. During the war Mr Zank was our block captain. When the sirens signalled an air-raid exercise, or possibly the real thing – we were never sure – he would don a British safari hat, the kind Stewart Granger wore in 1940s movies, and walk around the neighbourhood with a flashlight making sure all was dim and curtains drawn. When Germany surrendered on 7 May 1945 people flocked to the streets cheering, car horns honked, neighbours embraced, and Mr Zank’s expression seemed to indicate that he had done his part for the war effort. Over the following months our men started coming home, some on crutches, some in bandages, some totally whole, but all changed from the day when they were drafted or volunteered.

An 18-year-old kid would graduate from Lincoln High or Midwood High, go through boot camp at an army base in Georgia, bunking next to an 18-year-old from Alabama who would without rancour use the phrase ‘Jew you down’, or ‘he’s moving like a nigger in high cotton’, or ‘wop gangster’ – phrases you never heard when playing pick-up basketball in the schoolyard in Brooklyn. They would circle round each other, sniff each other out, and allow the scared human to emerge from the macho colloquial. The military experience was an equaliser. From the shock immersion of basic training to however fate would test them, the war was in them for the rest of their lives. They returned, took their uniforms off, stored in attics for grandchildren to discover someday. The G.I. Bill gave millions the gift of college, the joy of graduation without half a lifetime of payments. Jobs in abundance. General Motors. Procter and Gamble. Family businesses. Teachers. Lawyers. Plastics. They bought houses and cars and gave birth to the boomers. The sun was shining goodness on America. And being Americans, our goodness crossed the ocean to rebuild what we destroyed with the Marshall Plan. No rancour here.

January 1946. Adjusting to peace, rebirth, normality … and neighbours, relatives, everybody, asking: ‘Are you going to the parade?’ It was to be the largest military parade in history. On Fifth Avenue. In the city. Where we lived, Manhattan was the city. Even though Brooklyn was one of the five boroughs of New York City, referring to ‘the city’ meant the place where many fathers worked, where parents went to Broadway shows, took the kids to museums, Central Park Zoo. The four of us, me almost six, brother four, mother and dad, walked three blocks to the Brighton Beach subway station, a nickel each in the turnstile for the adults, kids legally slipping under, up metal stairs and onto the platform. Cold January gusts. Familiar neighbourhood faces. Subway spotted down the tracks. Roars to a stop. Pushed in by the crowd. Festive 45 minutes through Brooklyn, then underground. All pile out at 42nd Street and merge with the crowd to Fifth Avenue. We push and squeeze our way to police barriers at the kerb. Platoons. Companies. Battalions. Regiments. All in step. Left right left right. Boots shining. American flags. Regimental flags. Cheers and hats off as they pass. Men in uniform in the crowd salute back. Our men. Americans.

I sensed the patriotism thick in the air and felt a welling of pride. Not nativism. No exclusion here. We were all Americans and these were our men who fought and won, and we loved them, wanted to be them, and that’s why we took the subway to the city. During the following fifteen years there was contentiousness in politics, McCarthy, divorce, rape, illegal abortion, juvenile delinquents, race issues. But the glow of having triumphed over evil in Europe and the Pacific reverberated for more than a generation. Modell’s – where today you buy T-shirts expressing a range of sentiments, $120 running shoes, your favourite sports team caps, tennis rackets featuring lightweight miracle alloys – during that era was an army and navy store. Mess kits. Canteens. Web belts. Pup tents. Fatigue jackets. Navy pea coats. Ka-Bar knives. Paradise for teen and pre-teen boys. We would enter, inhale the dramatic aroma of canvas, our imaginations jolted to high fantasy. Were these combat boots on Tarawa, did this bayonet ever kill a Nazi in France, did any of those soldiers we saw in the Victory Day parade ever wear these fatigues? Each visit to Modell’s played a private war movie in our minds.

On one visit a barrel in a corner held several surplus rifles. A handwritten sign tacked to the barrel said .22 rifles. $8.00. Catnip. My brother, Allen, and I picked one up. Examined it studiously. Opened the bolt. Enticing metallic sound. Full stock Mossbergs. A British crest on the receiver. A salesman, older, with a nicotine-stained white moustache, maybe the owner, appeared. He said they were part of our Lend Lease programme. Explained that we sent them to England at the start of the war for target practice for the Home Guard. If we didn’t buy that rifle a crippling regret would haunt our lives for ever. Unquestionably for ever. I don’t recall if we had eight dollars between us or if we went home and begged, but the actual purchase is vivid. Nicotine Stains took the rifle to the counter, unrolled a long sheet of tan wrapping paper, carefully laid the rifle on the paper, folded and taped the treasure very professionally, I handed him the eight dollars, he said, ‘Be careful, boys,’ and we left Modell’s, got on our bikes with our beautifully wrapped Lend Lease Mossberg rifle and rode home. I was 14 years old. It was all perfectly legal. Living in Brooklyn in the 1950s we didn’t have many opportunities to shoot our new acquisition, as in those Remington rifle ads in Boys’ Life featuring a rural dad and son in the backyard plinking at tin cans. They wore plaid shirts, had big smiles, the boy cradling his Christmas rifle, the father holding a can peppered with bullet holes.

Not our lifestyle. Instead of shooting sessions out back, our father was more likely to attempt bonding by recommending a Chekhov short story. What to do? The apartment building next door had several shops, a dry cleaner, a glazier, a barber and a candy store. On a somewhat regular basis an NYPD squad car would double-park in front of the candy store and both policemen would sit at the counter taking their coffee break. So my brother and I were drinking egg creams when the two patrolmen sat down next to us, smiled, and Sadie, the owner of the store, in a stained apron, usually gossiping about neighbourhood goings-on in thick Brooklynese, automatically poured two cups of coffee. A eureka moment. I told the cop sitting next to me that we’d just bought a .22 at Modell’s and did he know where we could shoot it? He flicked his Camel cigarette and said there’s an indoor range in the city, at 24 Murray Street.

The range was in a sub-basement. Two flights down beneath the streets of Lower Manhattan, not far from City Hall. We could hear shots as we descended the second flight of stairs. It was dimly lit. There were about ten shooting compartments with pulleys to reel targets back and forth. The other shooters seemed to be off-duty policemen, bank guards. Two men with very impressive precision target rifles were wearing shooting jackets with padding on the shoulders. My brother and I paid the man in charge two dollars, he gave us some paper targets with black bull’s-eyes and pointed to an empty position. We inserted little foam ear protectors, removed the rifle from the case we had bought at a Sears store somewhere near Flatbush Avenue, where we had also purchased two boxes of cartridges. Fifty in each box. We then attached a target to the pulley, wheeled it out to the backstop, about fifty feet, then I leaned the rifle on the shelf as a rest, put a .22 cartridge in the chamber, closed the bolt, aimed through the rear peep sight and squeezed the trigger. Did that ten times. Couldn’t tell if there were holes in the target. Reeled the target in and all ten shots were in the black. Then my brother’s turn. He did the same and got most of them in the black also. The smell of gunpowder, the sound of the shots, the other shooters, wondering what the Home Guard men were like who shot that rifle at some range in England, this was fun.

When we were out of ammo the rifle went back in its case, we took the targets as souvenirs, walked back up to the street. Cabs, trucks, crowds, gas fumes. Typical downtown Manhattan. We walked to the subway, paid our nickel, through the turnstile, waited for the train, returned to the Brighton Beach stop and home. No one was suspicious of a 12-year-old and a 14-year-old with a rifle in a case. It was 1954.

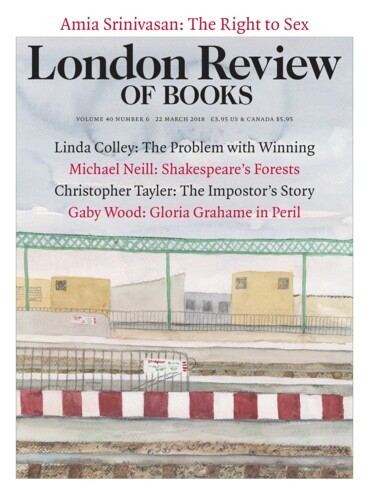

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.