The commune of Gurs in the foothills of the Pyrenees is famous for its internment camp, built by the French to house fugitives from Spain after the Republic fell to Franco in 1939. A succession of internees went through the camp before it closed on New Year’s Eve 1945. With the Spanish Republicans came International Brigade volunteers who couldn’t get home – Germans, Austrians, Poles. After the Nazi invasion in May 1940, the French began detaining ‘enemy aliens’: anyone of German (or Austrian or Sudeten) origin, including refugees from the Nazis, was suspect. The drafts of ‘undesirables’ in the summer of 1940 included nearly ten thousand women, hundreds with young children. Several were well known: Hannah Arendt; Dora Benjamin, Walter’s sister; Marta Feuchtwanger, wife of Lion; the actress Dita Parlö, whose character falls in love with Jean Gabin’s in La Grande Illusion; Lisa Fittko, a passeuse who risked her life guiding scores of refugees out of France across the Pyrenees – among them Walter Benjamin – before leaving by the same route. Several artists produced memorial sketches and artefacts, a practice begun by Spanish Republicans.

Charlotte Salomon, the German painter who created an extraordinary pictorial memoir during the war, was sent to Gurs in May 1940, or so it’s believed. The Salomon family had been dispersed by the rise of Nazism: Charlotte and her grandfather, Ludwig Grunwald, were living together in Nice at the time. If they were at Gurs they were released soon afterwards, making their way back to the Côte d’Azur under a cloud. Grunwald was elderly, frail and monstrous; wherever these weeks were spent, outside of Nice, he seems to have pressed his granddaughter to share his bed.

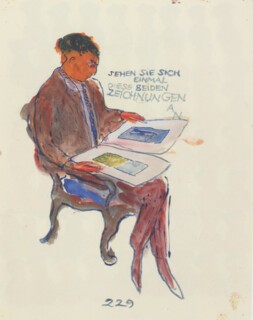

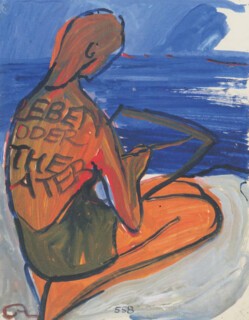

Not long afterwards, Salomon embarked on her life’s work: 769 gouaches on loose-leaf pages, 32.5 x 25 cm, many inscribed with text in German. In addition she painted around 340 glosses on tracing paper as overlays for the paintings, explaining the relevant scene or attributing words to the characters: if we think of the overlays as intertitle boards in silent cinema we’re not far off. Leben? Oder Theater? is the name Salomon gave the work, which remained packaged up in the South of France for several years after her death in Auschwitz in 1943.

Salomon supplies her title in a light-hearted introduction, or a playbill of sorts: she calls it a three-coloured Singspiel, or operetta, announces her dramatis personae, and promises music throughout. The work is both an elaborated script-cum-storyboard for a musical and its gala performance, staged in two dimensions. The complete Singspiel is currently on display at the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam (until 25 March). Duckworth’s new edition reproduces Life? Or Theatre? in its entirety, with translations from the German texts – both the paintings and the overlays. It also contains a crucial addition: a long letter written in paint by Salomon about the work and the turn her life had taken once she’d finished it. The contents of this letter appeared in full in 2016, appended to a French edition of Life? Or Theatre? Its inclusion here makes the book a landmark publication in English.

Life? Or Theatre? begins in Berlin in 1913, with the death of another Charlotte – Charlotte Grunwald, the artist’s 18-year-old aunt – who has thrown herself into the Schlachtensee. The prologue goes on to record the birth of Charlotte Kann, the Salomon persona, in 1917, her life as a girl, and then as a young woman. The main section deals almost in passing with the incarceration of Salomon’s father by the Nazis, and concentrates on her passion for the singing teacher, Alfred Wolfsohn, who becomes Charlotte Kann’s lover in Life? Or Theatre? (The imaginative truth of the work doesn’t require us to know whether Salomon and Wolfsohn were actually lovers.) At times the affair with the singing teacher is handled as elevated soap opera; at others it has a heady shapelessness as we’re led on a tour of his innermost thoughts about life, music, love and death. The main section ends with Charlotte Kann leaving Germany in 1938, after her father’s release. A rapid shift of scenery brings the curtain up on the epilogue: Charlotte is now with her grandparents on the Côte d’Azur, which is where her story concludes, in the summer of 1942, in a hurried suite of painted scenes. For the most part, Life? Or Theatre? focuses on Salomon’s family and the object of her desire, the maverick singing instructor. She assigns names to each of the characters she has drawn from life: her capable father, Albert Salomon, is Dr Kann; her stepmother, Paula Lindberg, a contralto who made her name in Berlin, becomes Paulinka Bimbam; her maternal grandparents, Marianne Benda and Ludwig Grunwald, are ‘Dr and Mrs Knarre … a couple’. Alfred Wolfsohn is ‘Amadeus Daberlohn … a voice teacher’.

Salomon’s parents were well-to-do. Her father, Albert, was a surgeon and oncologist; her mother, Fränze Grunwald, decided to become a nurse soon after her younger sister’s suicide. The family was comfortably installed on Wielandstrasse until, when Salomon was eight, her mother died suddenly. Salomon was told it was a bad case of flu; she found out much later that her mother, like her aunt, had killed herself. In 1930, Albert married Paula Lindberg, the orphan daughter of a provincial rabbi; she had fought her way to the music academy of Berlin, changing her name from Levi or Levy, and then to the concert hall. In Salomon’s play, Charlotte – now a reticent, troubled teenager – sees the point of Paulinka, even if she’s too quick to know what’s right for her stepdaughter and too busy to spend much time with her.

With growing restrictions on what and where Jewish artists could perform, Paula Lindberg depended on the Kulturbund, founded in 1933 by Kurt Singer, the former director of Berlin’s municipal opera house, to give excluded artists and writers the chance to work, lecture and perform. In Life? Or Theatre? we encounter Singer – whom Salomon renames Dr Singsong – writing up the proposal for the Kulturbund that he will take to the Nazi minister of propaganda. The Nazis welcomed the project as a way of quarantining Jewish talent from the Aryan canon and projecting an image of tolerance to the rest of the world. By the end of 1938, the Kulturbund was all but hollowed out – the Nazis closed it three years later – but in the early days Singer, one of several suitors Paula had turned down in favour of Albert Salomon, made frequent visits to the apartment on Wielandstrasse: in Life? Or Theatre? Charlotte Kann is vaguely jealous of the attentions Dr Singsong lavishes on her stepmother.

Sometime in 1936 or 1937 Singer passed an impecunious Jewish voice instructor on to Paula, who agreed to help him out by taking lessons. Alfred Wolfsohn, then in his early forties, had served in the Deutsches Heer in World War One. He suffered a prolonged bout of PTSD, followed by a stint in a psychiatric hospital, where he arrived at a therapeutic view of singing: good music was the objective, and painful self-discovery the process. Taking the Orpheus myth as a model, Wolfsohn asked his students to descend into themselves and retrieve the inspiration that had drawn them to singing in the first place (Orfeo ed Eurydice is one of several musical references in Life? Or Theatre?). Paula was already happy with her voice: she put up with his theories because Wolfsohn was beguiling and intense, and she was in a position to help another musician marginalised by anti-Semitic laws. It wasn’t long before Salomon took a shine to him, and he to her, though he was also smitten with her stepmother, who was polite but firm in the face of his ludicrous advances (‘when you smile, your hands smile too’). The ensuing love affair is rowdy and impulsive. Charlotte Kann plunges in: you can almost hear the splash in the brushwork as the couple appear alongside, over and beneath one another.

As Wolfsohn makes his entrance in the main part of Life? Or Theatre?, the overlay announces in blue-grey gouache: ‘Amadeus Daberlohn, prophet of song’ followed by a phrase from a German version of the ‘Toreador Song’ from Carmen. It’s hard to imagine anyone less like Escamillo in Carmen than the figure of Daberlohn when he first appears in Salomon’s piece, shuffling towards Dr Singsong’s office for word of a job. Salomon can be very funny – and knowing – about Daberlohn’s flatteries: in one painting she left out of the finished work, he is sitting naked with her astride him; the overlay reads: ‘I see you’ve got talent.’ But she packs her story with his free-ranging thoughts on the Orpheus myth, the damaged self and the majesty of the recovered voice, transcribed as if from memory. Wolfsohn was twenty years older than Salomon and gave her confidence in her future as an artist. In Life? Or Theatre? he holds the keys to all that is noble in the realm of the imagination.

Before they met in the late 1930s, Salomon was enrolled in the amalgamated Schools for Fine and Applied Arts in Berlin – a great achievement for a Jewish student. Her character, it was agreed, was beyond reproach; she was unlikely to corrupt male Aryan students. But what was the mood of the place when she entered? Blithe in denial? Tense and tight-lipped? At the Royal Society of Arts in 1936 Nikolaus Pevsner assured his audience that the Berlin Schools had the edge over the Bauhaus. By then the director, Bruno Paul, had already been dismissed. In 1937 the Nazis staged the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich. (Salomon, David Foenkinos imagines in his novel, ‘positions herself on the side of the despised artists’.) In 1938, she submitted a piece for an anonymous fine arts competition; having picked it as the winner, the jury panicked when they discovered it was by a Jewish student. The prize went instead to her friend and comrade, Barbara Petzel, whom we see only briefly in Life? Or Theatre? as a lovelorn blonde. On the overlay for a double portrait, they exchange confidences about Petzel’s love life. ‘We only kissed once, and they put me in a convent,’ Barbara tells Charlotte. Charlotte replies: ‘You only kissed once, and they put you in a convent.’ Not long after the fiasco of the prize, Salomon stopped attending her classes.

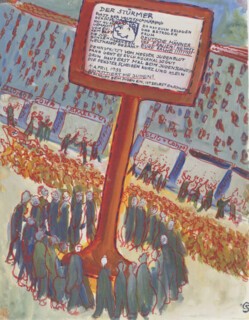

Albert Salomon was arrested the day after Kristallnacht and sent to Sachsenhausen, a morning’s journey north from Berlin. He spent several weeks in the camp. Life? Or Theatre? records his detention in two murky green images with uniformed overseers towering above him: something of the generic bullying male, as well as the racial persecutor, looms in these figures. Then, as the story flies forward, Paulinka has used ‘charm and intelligence’ to intercede on his behalf: Dr Kann is free. Charlotte Kann has been submerged throughout this drama in her relationship with Daberlohn, but notices that her parents’ friends are now thinking seriously about leaving Germany. ‘Australia’, ‘the United States’, guests announce in the overlay for a dinner party after her father’s release. A few scenes on, Charlotte Kann is looking out of the train window, heading west through Germany towards the border with France. A skyline of hectic pink and pale blue behind the departing train confirms that this is daytime, but the light in these final moments of the main section is leaden, like ‘the black milk of daylight’ in Celan’s ‘Death Fugue’: we can’t tell dusk from dawn. All the same, we can put a date to it: Salomon left Germany in December 1938.

Her grandparents, Ludwig and Marianne, were living with Ottilie Moore, an American heiress, on the outskirts of Nice. Moore’s villa, L’Ermitage, had ample grounds and outhouses. (The Taschen selection of Salomon’s work includes a lovely painting of one of the buildings.) Moore’s establishment was a place of asylum for many orphans and exiles thrown beyond the widening margins of the Reich. In Foenikos’s novel, Charlotte finds her way from the station to the gates of the property, where she pauses before ringing the bell. It is among the best passages in the book, which – like the work that inspired it – is written in the historic present. Each sentence begins on a new line, giving it the deceptive look of a long poem. The success of this approach, loyally managed by Sam Taylor in his translation, is to make Charlotte read as a series of ticker-tape bulletins, delivered in breathless fits and starts. At the entrance to L’Ermitage, something holds Charlotte back:

It is a force behind her.

She almost has the impression that her name is being called.

The force turns her around.

And she discovers the majestic sparkle of the Mediterranean.

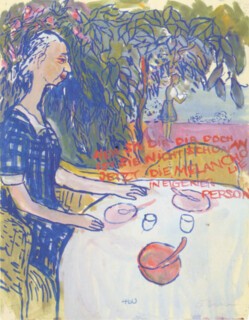

About two months after Salomon’s arrival in France, her father and stepmother flew out of Berlin on false passports. Kurt Singer was in Amsterdam to meet them. For the time being everyone was safe. But living with her grandparents was an ordeal for Salomon: just how much of an ordeal is clear both from the epilogue, which unfolds in her new surroundings, and from the letter appended to this edition of Life? Or Theatre? A beautiful opening scene shows many Charlotte Kanns sketching, painting and walking near the sea in a hyperbole of reds and blues. The young German – three images of her – is turning into a child of the Mediterranean in a blue swimsuit (four of her). All have their sketchpads out. In the next painting Charlotte, Ludwig and Marianne – ‘Dr and Frau Knarre’– are at a table with a view of the bay behind them. Their exchange is inscribed in painted capitals across the image. Grossmama (ambiguously): ‘Are you here in the world only to paint?’ Grosspapa (disobligingly): ‘Why shouldn’t she work as a housemaid, like all the others?’ The white tablecloth clings to the paper like icing on a birthday cake. In the final section of the work overlays are rare: tracing paper may have been hard to find, or perhaps a sense of urgency drove Salomon to commit text and image to the same page in energetic flurries of graffiti.

Sometime in late 1939 or early 1940, after Salomon and her grandparents had moved out of L’Ermitage to a flat in Nice, her grandmother tried to hang herself. In Foenkinos, the Nazi-Soviet invasion of Poland takes its toll on Grossmama’s deteriorating mental health. The paintings that follow Frau Knarre’s failed suicide in Life? Or Theatre? show Charlotte by her bedside singing siren songs to lure her grandmother away from a fresh attempt: ‘Ode to Joy’, out of Schiller, via Beethoven’s Ninth. The youngest member of the family is now protector and matriarch, a repository of the rich German culture that will keep her grandmother from her next dark thought. The following morning, we encounter Dr Knarre sitting up in a blue bed complaining to Charlotte, on a pink divan. His outburst is stamped in red across the composition: ‘What was all that kerfuffle? I couldn’t sleep a wink.’ In the next sequence, Charlotte is lavishing care on her grandmother, folding herself round her, the pair indistinguishable apart from their heads. In one muddy, khaki gouache, Charlotte seems to have flung herself across Frau Knarre like a soldier smothering a live grenade. Dr Knarre’s sleepless night has brought him to a pitch of anger. He reacts by marching Charlotte to the edge of the family precipice and asking her to topple into its suicidal past.

On a single feverish page of sketches, 13 stubborn little heads of Grosspapa are rapidly worked. Salomon weaves his account of the family’s suicidal history as a garland of angry text around the serial iterations of his head. In his rage he seems to have garbled the story and we lose track of the death count. In Foenkinos and in Life? Or Theatre? seven or eight family members seem to have killed themselves: Charlotte’s great-uncle (drowning) and his daughter (barbiturates), her great-great-uncle (falling), that uncle’s sister or her husband – ‘I don’t know any more,’ says Grosspapa in Charlotte. More recently, a cousin has killed himself (method unexplained) after losing his job ‘like all the Jews’. The worst of it for Charlotte is the news that her aunt drowned herself, and her mother threw herself from a window. Within thirty pages of Dr Knarre’s revelations, his wife has slipped her captors and thrown herself from a window of the apartment in Nice. Marianne Benda did exactly this in March 1940. A few scenes on in Life? Or Theatre?, Salomon foregrounds Charlotte Kann against the fires of hell. ‘Dear God, please do not let me go mad.’ To her right is the beckoning frame of a window.

Two months later the Phoney War has given way to the German invasion of France. A new intertitle panel – ‘may 1940’ – sounds the alarm. In Nice, ‘all German nationals are required to leave the city and the area without delay.’ Charlotte and Dr Knarre make a painful journey west on an overcrowded train, and in the next scene they are looking for lodgings (we can’t tell where). Charlotte protests that there is nothing ‘natural’ about sharing Dr Knarre’s bed. A new daylight scene, exterior: Charlotte, carrying a large suitcase, is overcome by the landscape: ‘God, it’s beautiful here.’ The two ravaged survivors of a family tragedy, now uprooted by world events, trudge forward. They stay at a hostel and Charlotte asks for a separate room; instead of her grandfather she has to fend off a German refugee. By now, the French authorities are allowing ‘undesirables’ to drift back to the cities. Charlotte announces to Dr Knarre that she’s found a train to get them back to Nice, or near enough. This obscure period in Salomon’s life, between leaving Nice and returning – when she may have been interned at Gurs – ends in July 1940, with an almost unbearable exchange between Charlotte and Grosspapa. Charlotte: ‘You know, grandpa, I have a feeling the whole world has to be put together again.’ Knarre: ‘Oh go ahead and kill yourself and put an end to all this babble.’

Salomon was not about to vanish from the world in the way that her grandfather proposed, but she took a leave of absence and began to paint with urgency. She emerged in the summer of 1942 in a state of febrile satisfaction, as she added her top and tail to Life? Or Theatre?: curtain up and curtain down. Salomon’s death in Auschwitz the following year has brought a deluge of historical hindsight to bear on her work, and as Darcy Buerkle explains in Nothing Happened (2013), a scholar-sleuth’s extrapolation of Salomon’s work and the context of its making: this inflects the way Life? Or Theatre? is curated and understood: very often as a Holocaust document, despite its emphasis on Charlotte’s navigation of her own family history.

In order to see Salomon as a Jewish artist of the Holocaust, it makes sense to place her in Gurs during her short exile from Nice. Most of the sources locate her in the camp at some point in the summer of 1940: the diligent Mary Felstiner; Foenkinos; Jacqueline Rose in Women in Dark Times (2014); Belinfante in her essay for the Taschen selection; Griselda Pollock in her momentous new study, Charlotte Salomon and the Theatre of Memory. There is no official trace of Salomon or anyone else detained at the time: the camp administrators destroyed the records in June 1940. But the Gurs memorial archive shows that dozens of artists were detained there and the unofficial count is rich: memoir, journalism, photographs, paintings and drawings allow us to identify many people whose detention would otherwise have gone unrecorded. Even so, Salomon can’t be found in Vivre à Gurs (1979), an account by the Polish intern Hanna Schramm of her time in the camp, or in Les Oubliées (2007), a memoir by a German intern, Lilo Petersen, held in 1940. Nor is there any mention of Gurs in Life? Or Theatre? itself. Charlotte Kann’s excursion from Nice shows her on trains, in hostels and open landscapes, and is described either in shorthand odes to joy – ‘God, how beautiful’ – or expressions of dismay about her grandfather.

The assumption that Salomon was in Gurs has its origins in only one source: a document written by Emil Straus, another refugee on the Côte d’Azur who became friends with Salomon and her grandparents and wrote a long introduction to the first edition of Salomon’s paintings in the 1960s (Paula cut the text to the bone). Buerkle is sceptical. She points to a letter written in 1961 by Salomon’s father, Albert, in which he reports that few of the people in southern France whom he’d met or contacted after the war believed that his daughter and father-in-law were ever in Gurs. But the question mark hovering over this brief moment in the summer of 1940 is no longer interrogative. Albert’s doubts have been erased, making Salomon’s flight from Nice a foreboding of her death in Auschwitz, even though the evidence is scant. Pollock must know this: she argues that the absence of Gurs from Life? Or Theatre? is a subconscious excision, the sign of ‘a traumatic gap’.

There is a greater difficulty: if Life? Or Theatre? is to be glossed and archived as a narrative of anti-Semitic persecution, how can this be reconciled with the central theme – serial suicides in the family that predate Weimar? One approach is to test Life? Or Theatre? against as many models as possible, to gloss what Salomon may have thought she was painting – a survivor’s narrative of family life, a record of love and inspiration, an artist’s autobiography, and historicise when necessary. If anybody has the discursive stamina for this, it’s Pollock. Life? Or Theatre?, she writes, ‘solicits all my feminist, Jewish, post-Holocaust, modernist, psychoanalytical, transdisciplinary interests as an art historian’. Her book is a dazzling aggregation of ideas and approaches, and includes images which we wouldn’t otherwise have seen, among them key paintings that Salomon didn’t select for the final version of Life? Or Theatre? and photos of the artist and her family that situate an endangered German bourgeoisie in the preamble to the Holocaust.

Pollock’s all-encompassing gloss on Life? Or Theatre? puts the work under enormous stress, but her approach is a generous one. She pays scrupulous attention to the paintings, tracing their ancestry and affiliations across the sprawling genealogies of European art. She awards Life? Or Theatre freedom of association with the cultures of Salomon’s period and either side of it: with the writings of Walter Benjamin above all; with European cinema, from Murnau through Leni Riefenstahl to Michael Haneke; with Freud’s Moses and Monotheism; with mid to late Derrida; with Barthes, the decoder of the close-up face in cinema and the figure in the still photograph. She shows us the swaying edifice of Weimar as it goes down, and the horrors that followed.

On the face of it, Life? Or Theatre? is the story of a young woman who was meant to kill herself and fought her way back from the brink by deciding to paint. In Pollock’s ambitious grid of assimilations, we sense that the suicidal trace in the family is a metonym for something larger and more awful at work in the world: war and the extermination of the Jews. Buerkle and Felstiner are good guides in this murky area. Buerkle explains that suicides in the Jewish population were seen by the Nazis as a symptom of genetic and cultural decadence. As Felstiner remarks in her biography, the prohibition of suicide ‘on personal grounds’ in the SS was one of many ‘Aryan’ assertions in the face of ‘Jewish-fostered promiscuity, abortion, homosexuality and, of course, Selbstmord’. When Buerkle returned to Durkheim’s founding study of suicide in 1879, she saw an evidentiary bias that played down suicides by women, especially Jewish women. In the Weimar period, suicide rates were high in Germany; three or four times higher in Berlin in the mid-1920s than in London. In Prussia, Jews were taking their lives in larger numbers than Catholics and Protestants, even though it was hard to dislodge the conventional wisdom that suicide was committed mostly by men raised in Catholic and Protestant cultures.

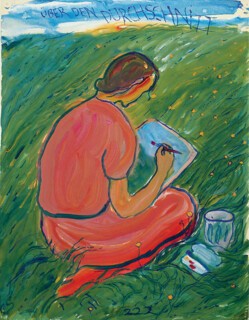

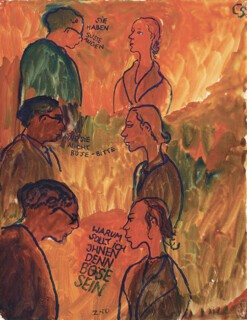

Felstiner is right to say that the death of Salomon’s mother, Fränze – a Berliner, a Jew, a woman – ‘was not anomalous, it was exemplary’. By the time Salomon left Germany in 1938, a progenitor’s death by suicide had been added to the list of traits that pointed to Jewishness in anyone who might otherwise have passed as Aryan. Salomon’s resistance – despite her circumstances, despite her grandfather’s goading – is also a refusal to play the role of Nazism’s despicable, suicidal other, and it’s not far-fetched to think of her as insubordinate: if the Nazis wanted her dead they would have to see to it themselves. In this light, the (rare) scenes in Life? Or Theatre? that bring us face to face with Nazism and anti-Semitism – a rally on the day Hitler is named chancellor; a crowd gathered round a Der Stürmer poster (‘The Jews have only made money from your blood’); Nazis heckling during a performance by Paulinka; Kristallnacht, Dr Kann’s detention – reverberate across the other scenes. It’s obvious, too, as the story unfolds, that the casement window is the device, or emblem, of the Knarre family. Alluring windows abound in the work. But they function, too, as a premonition, then a memory, of less intimate forms of horror and breaking, of Kristallnacht itself.

In a gouache from the main section, showing Charlotte Kann after her father’s arrest, she has her hands to her mouth: ‘I can’t take this life anymore. I can’t take these times anymore.’ But Salomon did, largely by immersing herself in her work. Many of her characters from the scenes in Berlin are frenetically active in the same way. Paulinka and the Kurt Singer figure, Dr Singsong, launch themselves at the Kulturbund. Daberlohn is ablaze night and day with his visionary notions and compulsive philandering. Charlotte’s father, Dr Kann, is a surgeon and oncologist in high demand. Everyone who was pretending that ‘nothing’ was happening made a point of being busy. Salomon carried the habit with her to Nice, along with the music that animates Life? Or Theatre? The songs of her days in Berlin were still in her head, their lyrics blaze in capital letters across the images: contemporary hits by the Austrian composer Fred Raymond; Old and New Testament settings by Bach (Paula Lindberg’s forte); snatches of Weber and Schubert (the Winterreise and a setting of Goethe); a flash of Mozart; generous amounts of Bizet. When Salomon briefly took rooms at a pension in St Jean Cap Ferrat in 1942, the owner recalled that she was forever humming and singing as she churned out her paintings around the clock.

What happened after Life? Or Theatre? was completed in the summer of 1942? By then Ottilie Moore had left L’Ermitage for the US. Salomon and her grandfather were living separately, she at St Jean Cap Ferrat, he in Nice. Many refugees were drawn to the city because it was administered by the Italians, who had no intention of enforcing Nazi regulations about the Jews. Grumbling French anti-Semites, Felstiner tells us, had begun calling Nice the new ‘capital of Palestine’. In February 1943 Grunwald died: in Felstiner, he ‘collapsed in the street’; Foenkinos describes him making for a pharmacy. It was either at this point (Felstiner) or just before (Foenkinos) that Charlotte returned to live at L’Ermitage, where she had begun a relationship with Alexander Nagler, a Jewish Austrian refugee.

At L’Ermitage Salomon sorted through her paintings and overlays, putting Life? Or Theatre? in order, then packaged it up and gave it to Georges Moridis, the doctor who had ministered to her grandparents, for safekeeping. In the summer of 1943 Salomon and Nagler were married in Nice. On instructions from the Nice prefecture, Salomon had already registered as a Jew by the time of the ceremony; the marriage of two Jews, residing at L’Ermitage, was now on record as well. In September, as Italy prepared to sign an armistice with the Allies, the Germans hurried the Italian administration on its way and the final solution, all the more zealous for running behind schedule, arrived in the Alpes Maritimes: nearly three thousand deportations in Nice alone would follow. Salomon was several months pregnant and living quietly with Nagler when they were denounced and arrested. They were transferred to Drancy and from there to Auschwitz. Salomon was murdered on arrival, Nagler died later.

Albert and Paula survived. Having been arrested in Holland, they escaped from a transit camp and hid out for the rest of the occupation. Not long after the war they travelled to Nice to find out what had happened to their daughter. Moridis had handed over the work to Ottilie Moore when she returned to L’Ermitage in 1946. Moore presented it to Albert and Paula. Along with the piece itself came discards excluded from the final version. Often when Salomon decided against a painting she would glue strips of tape over the characters’ mouths and eyes, in a conclusive muting and blinding: she had a firm editorial view of her own work and full control of her characters. The Salomon trove also included the long letter in painted text that was addressed to Daberlohn, the name she assigned to Wolfsohn in Life? Or Theatre?, and dated the month of Grunwald’s death.

Salomon’s work emerged slowly. In 1961 a modest show was held at the Stedelijk in Amsterdam. Albert and Paula also agreed to a book of 80 reproductions, published in 1963 and proposed as a ‘diary’, even though Life? Or Theatre?, a fantastic memoir completed in two years, was clearly nothing of the kind. A key painting near the end, where Charlotte Kann tells her grandfather that things must start again from scratch (‘the whole world has to be put together again’), appeared for the first time in public without his reply (‘Oh go ahead and kill yourself and put an end to this babble’). At Paula’s insistence, Grosspapa’s words were carefully excised from the image, a technical feat on the part of the printer.

In 1971, the paintings were turned over to the Jewish Historical Museum in Amsterdam; a number were exhibited in 1972. Along with the finished work came Salomon’s ‘deselections’ and what’s now known as the letter to Daberlohn. Or rather, parts of the letter: many pages were missing, and after Albert’s death in 1976, Paula let it be known that she was holding them back. In 1981 the museum showed 250 scenes from Life? Or Theatre? in sequence, and critical attention took off. In 1998 a show at the Royal Academy sealed Salomon’s reputation. Then, in 2004, the paintings were shown at the Städel Museum in Frankfurt, alongside work by Munch, Chagall, Matisse, Kokoschka and Emil Nolde, with the idea of releasing Life? Or Theatre? from its shadowy niche position – unfashionably reliant on narrative; arguably art brut; arguably a Holocaust object – and edging it towards a proper modernist status. Through all this, the missing sections of the letter remained hidden, including a passage in which Salomon describes how she killed her grandfather by lacing an omelette with his emergency veranol: a fatal care package of the kind many Jewish refugees were in the habit of carrying on them once the reality of their situation had sunk in.

The relevant passage in the letter couldn’t make matters more clear:

And now comes – my confession, which is why I am writing these lines to you: I was sick with despair!!! When my grandparents left Germany they brought with them poison morphine opium veronal for taking their lives together when the money ran out. My grandmother didn’t think of the poison and my grandfather had kept away from it – because suicide goes against – as he expresses himself – his nature – I knew where it was – As I write, it is working. Maybe by now he is already dead.

Salomon goes on to describe how Grunwald ‘fell asleep by intoxication with the “Veronalomelette”… as I made a drawing of him’. It’s easy to imagine how it might have gone from there: she puts down her sketchpad and leaves the apartment. At some point he wakes and struggles down to the street towards the pharmacy, dying on the way.

In the mid-1970s the missing pages were shown in strict confidence to Frans Weisz, a Dutch filmmaker, and the writer Judith Herzberg, who were preparing a feature about Salomon. They made a transcript and returned the originals, which have never been seen since. One other person, Belinfante, read the confession and – like the filmmakers – complied with Paula’s wishes, and, perhaps, the curatorial imperatives of the Charlotte Salomon archive. In 2012, Weisz came out with a documentary on Salomon that made use of the confession, and Salomon scholarship hit a spell of turbulence.

As Buerkle explains, early attempts to portray Salomon as another Anne Frank had served her well enough in the 1960s. The presentation of her work and life in terms of a Jewish catastrophe was always implicit in the curating, but for this approach to work the notion of innocence – or at the very least bourgeois German propriety – had to remain intact: young women who kill their elders are not the people we’re supposed to think of when we commemorate the Holocaust. Anglophone pioneers of the Salomon archive – Felstiner, Buerkle and Pollock – were well placed to absorb the shock of the confession: whatever their feelings about a Jewish curation of Life? Or Theatre?, they were already proposing Salomon as an intersectional figure, both a member of a targeted ethnic minority and a woman in a desperate situation compounded by the behaviour of an older relative. But Pollock has spelled out clearly what Felstiner and Buerkle have kept to themselves: that Grunwald was a serial abuser whose behaviour may have led to the suicides of his two daughters, Charlotte and Fränze, before he turned his attentions to his granddaughter. Pollock points to a painting in Salomon’s prologue which shows a vast skeleton standing in the grandparents’ apartment, and a little girl fleeing between its legs. This alerted her to family abuse, she says, in the 1990s. ‘Yet, even then, I did not dare to speak the implication of what was there before me.’ Her inhibitions have since given way to a reconsideration of Life? Or Theatre? as a testimony to family abuse and other atrocities, at the risk of dragging it into the realms of grand guignol and misery memoir.

Reflecting on the tussle over Salomon’s status as a ‘Holocaust artist’, Buerkle writes that where ‘one set of critics diminishes her by linking her work to the Holocaust, another set truncates it by trying to avoid that link.’ A similar dilemma arises where scholars feel bound to designate Life? Or Theatre? a Jewish or a gendered work. Felstiner resolved it 25 years ago, identifying Salomon as the victim of a twofold persecution and drawing attention to ‘the stealthy, intentional murder of a Jewish female sex’. She reasons in part on the basis of slave labour statistics in Auschwitz-Birkenau over the years: of those arrivals in Auschwitz singled out for a stay of execution as forced labourers, only 32.5 per cent were women. ‘It was the weighting of each stage of the Final Solution against women that counted in the end,’ she writes. ‘In that crucial moment on the ramp, one sex was chosen disproportionately for death’ – in many cases taken straight to be murdered without registration or tattooing.

In comparison with these large facts, the life-threatening presence of Salomon’s grandfather for the women in the family, if that’s what it was, and her decision to poison him, if that’s what she did, should pale into personal tragedy. (Grunwald’s first daughter killed herself 20 years before the Nazis seized power.) But for Pollock this aspect of the story can’t be relativised; the confession hints at something immense in its own right and in its implications for the work itself. ‘I now recognise,’ she writes, ‘that what Leben? Oder Theater? shows in true crime-fiction fashion is something everywhere exposed and visible but hidden amid so much else that offers equally plausible answers to what the work is about. [It] hints at a crime that has already been committed, and repeatedly, against the women of the artist’s family, and finally, it seems, against the artist herself, a crime from which they all seem to seek escape through self-inflicted death.’ In Pollock’s reading of the confession, the motive is stable but the deed is mobile: the murder of the grandfather is really a transposition of other murders – the ‘soul murder’ already ‘committed by the old man of several young women’.

Life? Or Theatre? looks a little tenuous in the light of this psycho-forensic inquiry. I’m inclined to think of it as a late piece in the modernist canon that scrambled in just as the gates were closing. But if Pollock is our guide then Life? Or Theatre? will survive as a symptomatic document, overcast by family abuse and genocide. Pollock expresses her willingness to ‘keep open the space between the postscript and the art-working of Leben? Oder Theater?’, but by embedding the letter in our understanding of the work she closes the gap decisively. There are certainly grounds for seeing it as part of the work. It was addressed to Amadeus Daberlohn, one of Salomon’s characters, that’s to say, and not to a person. This gives it the hallmark of ‘a literary device’ – Pollock’s words – continuous with the rules governing Life? Or Theatre? Pollock’s use of the term ‘postscript’ to describe the letter is not a radical departure: Felstiner used the same word about the incomplete letter she was shown in Amsterdam in the 1990s. Even if she meant it for Wolfsohn’s eyes, Salomon packaged up the letter with her piece. The inclusion of the letter in the 2016 French edition, and now the English edition of the ‘complete’ work, made Pollock’s drastic reconciliation between the artist and the murderer, the work and the murder, unavoidable: even the marvellous exhibition now showing at the Jewish Historical Museum includes facsimiles of the surviving parts of the letter and the typescripts that show us what was on the missing pages.

We can’t rule out the possibility that with her great work done and dusted, a vestige of Charlotte Kann returned to stage a symbolic coup de grâce; that Salomon saw one more imagined scene for Charlotte: the murder of Grosspapa. Even so, the free indirect mode of Charlotte Kann has given way to an impassioned first person; other details in the letter, describing her life on the Côte d’Azur, have the authenticity of unembellished memoir. Pollock points out that the painted text may be a fair copy from rough. It’s among her best observations. If Salomon did take her grandfather’s life, she would have wanted to account for herself in a clean document, without erasures or revisions.

Elsewhere in the letter to Daberlohn, Salomon seems to have emerged from a painful, narcissistic struggle for survival and taken notice of the war in Europe. The elements so seldom foregrounded in Life? Or Theatre? now preoccupy her. She has seen ‘the whole world fall apart … I saw it turn to chaos.’ She speaks in a grandiloquent way about art and the artist’s soul, and about the state of humanity: it’s not Nazism so much as ‘the old calcified rules and laws of high-level conformism’ that are to blame for this ‘deluge’ that threatens to sweep her away. But she also knows that ‘Mr Hitler made it his mandate to destroy Europe’s Jews’ and she needs to consider her safety. That, she writes, is the reason she got together with Alexander Nagler, someone she imagined might protect her. What better apology to Wolfsohn for her forthcoming marriage to this inept, providential ally? Salomon’s prospects had begun to look bleak, even though Nice was still under Italian administration.

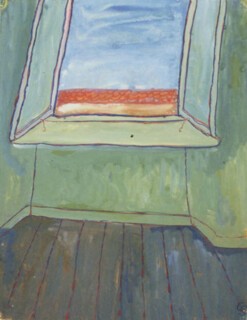

On the last page of Life? Or Theatre? the title is inscribed on Charlotte Kann’s back. She’s in a swimsuit, facing away from us, working on a sketch or painting. Beyond her is a garish, exhilarating view of the Mediterranean: the deep blue of the sea, the lighter blue of the sky, flecks of red denoting the horizon. Kann, the character, and Salomon, the painter, come together in this ironic reference to the art of the self-portrait. In her moment of triumph she can foresee the reputation her work will enjoy. The question mark after ‘Leben’ is barely visible. The other has disappeared.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.