In his biography of the painter Chaïm Soutine, Monroe Wheeler tells the story of Soutine’s obsession with Rembrandt’s Woman Bathing of 1654, which shows his wife, Hendrickje Stoffels, standing in a pool of water, gingerly hitching up her skirt. Rather than copy the original, Soutine took the unorthodox approach of restaging the scene and painting his own version first-hand. After ‘wearisome research’ in the countryside around Chartres, Soutine found a peasant woman in a field, whom he persuaded to stand in a small pool for days on end while he worked. Even when a storm broke out he refused to let the woman move. ‘The rain fell, the thunder rolled … but Soutine went on working. At last he came to his senses and was surprised to find himself drenched to the skin, and the model in hysterical tears, shaking with cold and fright.’

Such a dramatic search for authenticity was typical of Soutine, whose inability to work away from the subject – from drawings, or from memory – has become a standard part of his story. It was as if every painting had to be a terrible battle with reality. The goal was not greater naturalism, but rather to convey the sense of a dizzying encounter untethered from habit and convention. You can see this in Soutine’s early landscapes, made in the decade or so after he emigrated to Paris from Lithuania in 1913. Roads tilt vertiginously, houses collapse into diagonals, trees fly through the air, as if each landscape was shown in the process of being blown away.

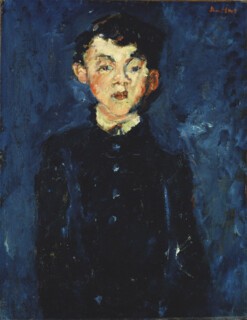

Soutine’s portraits show a similar dramatic encounter, though they are always balanced by the image of the sitter, which is preserved in caricature rather than being lost to abstraction. This is particularly the case with the thirty or so images of uniformed chefs, hotel workers and domestic servants that Soutine began painting at Céret in the south of France in 1919. They made his name – and his fortune – after one caught the eye of the American collector Albert Barnes, who went on to amass a large body of Soutine’s work.

More than half of Soutine’s uniformed portraits have been brought together for the first time for Soutine’s Portraits: Cooks, Waiters and Bellboys, at the Courtauld until 21 January. They span the major part of Soutine’s working life, and show the evolution of his style. One of the earliest, a painting of a butcher’s boy, was made at Céret in 1919. At least, it is titled Butcher Boy – there is no real way of knowing who or what the sitter was. It seems rather a mess of a painting at first, an attempt to paint in a vigorously anti-naturalistic style, but then you begin to see how Soutine suggests form without illustrating it: he draws a hot red shadow around the face, for instance, to give it volume and relate it to the background (a red curtain that someone once recalled Soutine obtaining from the butcher’s shop in Céret, perhaps explaining the title).

The attraction of uniforms to Soutine seems to have been largely the opportunity they offered for painting uniform areas of colour, enlivened by tiny touches of chromatic variation – an excuse for pure painting. David Sylvester said of Soutine’s landscapes that the motif is ‘secondary to the forces it has unleashed’, and the same holds true for the portraits. Flickers of colour only half follow the folds of the white uniform in The Little Pastry Cook (c.1922-23), which otherwise pursue their own painterly logic; seen in close-up they could easily have been made a few decades later, and it is no surprise to learn that New York School painters such as William de Kooning and Lee Krasner were fans. The white shirt of Pastry Cook of Cagnes (also c.1922-23) reveals transparent glazes, layered and interspersed with chromatic wisps, like some elaborate dessert. Delicate touches and squiggles form the cook’s face, built up with no blending or blurring to give a hardness to the otherwise distorted features, which hang anxiously between two huge and ornate ears. The one part of the physiognomy that Soutine paints with consistent restraint and seductive tenderness is the mouth – his male sitters have bowed, rouged lips, just like those of the women he painted. Grey scumbling to the left of the painting veils a red background, knocked back to keep the focus on the face, and the pastry chef squeezes a red neckerchief in his hands.

These portraits culminated in the images of waiters, bellboys and valets made in the various hotels in which by the late 1920s Soutine could now afford to stay. Four portraits of the same sitter, an unsympathetic-looking individual, have been brought together at the Courtauld. Red-haired, he wears a carmine waistcoat over a white apron, and is variously identified as Head Waiter, Room Service Waiter and, twice, Valet. His variety of roles is matched by the variety of painterly gestures and the very different moods across the paintings, from a Kokoschka-like expressionism to a Corot-esque classicism, showing Soutine’s inventiveness with a single motif.

Yet for all the movement within and between paintings, the sitter remains to a large extent a static caricature. All of them have an on-duty, officially alert look. The depth of the portraits as paintings is at odds with their lack of psychological depth, aside from the expression the subject happens to have put on for the sitting. This raises a question not asked in the exhibition or catalogue (which contains excellent essays by the show’s organisers, Barnaby Wright and Karen Serres, as well as by the painter Merlin James): are these really cooks, waiters and bellboys? Initially this seems to have been the case. The first pastry cook Soutine painted – the subject of the first painting Albert Barnes bought – was tracked down decades later, and identified as the at-the-time 17-year-old apprentice chef Rémi Zocchetto, who worked at a hotel in Céret. He told the journalist who found him that Soutine had offered him a painting instead of payment. ‘I was a fool to refuse,’ he said, ‘but his paintings seemed to me awfully bad,’ he said.

But there is no evidence that the subsequent sitters were not just models dressed up to play a part. Soutine was used to staging scenes, as the Rembrandt story shows, and he only liked to work in his studio, not in the hotel rooms where he stayed. He could easily have borrowed or rented the uniforms, and it would have been much easier to have sitters dress up than get actual bellboys and cooks to sit: their long working hours, noted by Serres in her catalogue essay, would surely not have accorded with the long sittings required to make a painting. It is perhaps a little odd to suggest, as Merlin James does, that the sitter in The Little Pastry Cook of c.1922-23 could be mistaken for a clown or a priest – he really couldn’t – but Merlin’s conclusion that a part is being played certainly seems right.

All of which is to say that the motif was, as always, secondary to Soutine – an excuse to paint, to unleash pictorial forces. In the late 1920s he shifted from hotel staff to domestic servants, and the elaborate white blouses and red livery of the earlier works are exchanged for simple aprons. The results are less thrilling and the paintings have none of the attention to fabric and costume that elsewhere evokes the bravura flecks and dashes, transforming into frills and buttons, of Venetian painting. It may be also that these really were domestic servants: it was surely easier to engage them for sittings while living on the estate of his patrons, the Castaings, just north of Chartres, where at the same time he was painting a peasant woman as Rembrandt’s wife.

Frank Auerbach once expressed his admiration for the ‘poverty’ of Soutine’s paintings. Whatever the identity of the sitters, it was Soutine’s great achievement to retain this feeling of poverty, derived from his early life as the archetypal peintre maudit, into a life of wealth and success. ‘Poor artist’s painting has to do with material painted under great harassment,’ Auerbach wrote, ‘as though if it weren’t done now it would never be done.’ And this is what holds our attention in Soutine: the sense of something happening, a moment unfolding, a question hanging in the air awaiting a resolution – which of course never comes.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.