In October 2016, three years after it was closed, I went to Reading Gaol. The prison had been laid out in 1844, each floor cruciform, so that all four corridors could be seen from a single, central vantage point. In cell after cell where, most recently, young offenders had been held, there was a set of metal bunk beds riveted to the wall, with a small table and two stools opposite, and a metal sink close to the small window, high in the wall across from the door, and a toilet on the other side of a small partition. The idea of what it might be like to be here all day and night, cooped up with another person, was fully palpable.

The jail was temporarily open to the public, courtesy of Artangel, an organisation that promotes the showing of art in odd and unexpected places. I had agreed to be locked in Oscar Wilde’s cell, the cell known as C.3.3, on the third floor of Block C, for an entire Sunday afternoon, to read an almost complete version of his De Profundis, which would take five and a half hours. It would be streamed onto a screen in the prison chapel; visitors could also come and look into the cell through a peephole in the door, though I could not speak to them, or they to me. All I could do was read Wilde’s text in the very space where it was written, written at a time when prisoners were held in solitary confinement, when they were forced to maintain silence, even in the short spell each day as they circled the exercise yard.

De Profundis, a 55,000-word letter addressed to Lord Alfred Douglas, written by Wilde during the final months of his two-year sentence, is a strange literary creation, a hybrid text. It was the only work he produced while in jail. On 4 April 1897 the prison governor informed the Prison Commission that each sheet of the manuscript ‘was carefully numbered before being issued [to Wilde in his cell] and withdrawn each evening’, but it is more likely that Wilde was given some freedom to revise and correct the pages. When he was released, Wilde gave the manuscript to his friend Robert Ross, who had two copies made. He sent one to Lord Alfred Douglas; the other he later lodged in the British Museum. Sections from Ross’s copy were published in 1905 and in 1908. The complete version, based on the original manuscript, wasn’t published until 1949.

De Profundis is a cross between an intimate address, full of accusation and urgent statement, and a set of eloquent meditations on suffering and redemption and self-realisation. It is a love letter and a howl from the depths. Its tone is hushed and wounded. It is written with passion, intensity and some wonderfully structured sentences. It is lofty, haughty, proud, and also humble, soft-toned, penitent. It was written in a set of different moods rather than composed by a stable imagination. It darts, shifts and often repeats itself. It was created for the world to read and composed for the eyes of one man, sometimes all at the same time. It is a great guilty soliloquy about love and treachery, despair and darkness.

When I was alone in Wilde’s cell that October Sunday with the pages in front of me, pages I had already read over and over in silence, I still had a problem. I did not know what sound the sentences Wilde had written in this solitude should make if they were to be read aloud. I did not know what the voice should be like were these words to be spoken to these cold four walls. Theatrical? Angry? Passionate? Dramatic? Or quiet? Hushed? Whispering? Or trying to find a voice that was real, a voice that needed desperately to be believed or heard, or, maybe even more important, a voice that sought to re-establish its own sound so that the speaker’s identity and sense of self, so crushed by solitude and prison rules, could find a space again. The letter was written by a prisoner to someone who was free, by an older man to a younger one, by a writer to an idler, by the son of a man who had earned his privilege to the son of a man who had inherited his.

But it was also written by an Irishman to an Englishman. And it was that last idea that gave me a clue about how to start speaking the words that Wilde had written. I would speak them in my own voice, as though I was talking to one person only, and see as I went along if I would find out something new about the text that might have eluded me in all my silent readings of it. What I noted as I read was not only the venom that came to the surface at any mention of Douglas’s father, the Marquess of Queensberry, but also the disdain Wilde felt for Queensberry’s whole clan, as though he were a figure from a lesser culture or indeed a lower species. The conflict in De Profundis was not only between the writer and the recipient, but also between Wilde’s pride in his own class, his own family, and his despising of the entire world that had produced the Douglases. Wilde left himself in no doubt about what he thought of Douglas’s family, or of the hospitality Douglas’s mother had offered, what he called ‘the cold cheap wine of Salisbury’. He resented being used as a pawn in the game between father and son: ‘I had something better to do with my life than to have scenes with a man, drunken, déclassé and half-witted as he was.’

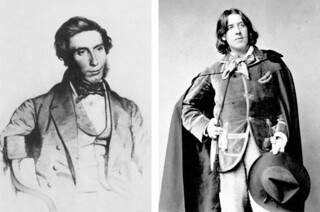

The word ‘déclassé’ is interesting here. In De Profundis, Wilde refers to Lord Alfred Douglas as ‘a young man of my own social rank and position’. But this view, in a country acutely alert to differences in rank, would not have been widely shared. Wilde was merely the son of an Irish knight while Douglas came from two aristocratic families and was a peer in his own right. Wilde’s father worked for a living; Douglas’s father had inherited his wealth. In Douglas’s world, Wilde was an interloper. In the message he left at Wilde’s club, the message that would cause the famous libel action, the Marquess of Queensberry alleged that Wilde was ‘posing as a somdomite’, as he spelled it. He might have added that Wilde was also posing as someone who held a social rank and position higher than it really was. This, in the England of 1895, may almost have been seen as a more serious accusation. But Wilde came from a long tradition of Irishmen who had created themselves in London. He was an artist, he moved freely in society, often using an English accent. He had been to Oxford. He invented himself in England much as his parents had invented themselves in Dublin. In De Profundis, he suggests that his own wit and cleverness were themselves a sort of social rank.

This idea of rank coming from words and wit had belonged to his parents too. In the absence of any other aristocracy in residence in Dublin, Sir William and Lady Wilde represented a type of grandeur that they had built with their books and their brains, their independence of mind and their high-toned eccentricity. When Wilde describes himself in De Profundis as ‘a lord of language’, he is suggesting that this title is far loftier than Lord Alfred Douglas’s. It was a title that his parents, in the books they wrote and the lives they lived, had handed down to him. When he lists what he lost at the time of his bankruptcy, he includes the ‘beautifully bound editions of my father’s and mother’s works’. In passing, he refers to lines by Goethe, which his mother often quoted, ‘written by Carlyle in a book he had given her years ago, and translated by him’, as though it were the most natural and ordinary thing in the world for Carlyle to have given a book to his mother. But the most significant passage comes shortly after he has been given the news of her death: ‘She and my father had bequeathed me a name they had made noble and honoured, not merely in literature, art, archaeology and science but in the public history of my own country, in its evolution as a nation.’

As I went on reading the letter, with light from the same sky coming into the cell as when Wilde was there, I became interested in the silences that lurk between the words in De Profundis, the things Wilde glosses over, that he seems almost to avoid. While Wilde has time to say everything he needs to say, there is one figure all but missing from the pages of his letter, a figure whose life has a considerable number of echoes with the life of Wilde himself. This figure is his father, a man who was more than twenty years dead when Wilde began to write De Profundis. Since Wilde put so much energy into letting it be known that he had invented himself, it is easy to understand how having a father might have seemed at certain moments quite unnecessary for him. Posing as a fully-fledged orphan was another of his modes. But as with Lord Bracknell in The Importance of Being Earnest, his father does not need to appear to inform his version of who he is. While Sir William’s books and the name he bequeathed to his son are mentioned in De Profundis, there is no moment when his father is fully evoked, no moment when anything particular is said about who Sir William Wilde was, and what he did, nothing about how his own search for fame has strange echoes with events in the life of his son, nothing about how Oscar Wilde emerged not, like Jay Gatsby, from his Platonic conception of himself, but from a family, or the fact that many of the ambiguities in his personality, and many of his talents, came from his father.

William Wilde , the son of a doctor, was born in County Roscommon in 1815, and studied medicine in Dublin. In 1837, the year his first illegitimate child, a son, was born, he embarked on a cruise of the Mediterranean. His first book, entitled Narrative of a Voyage to Madeira, Tenerife, and along the Shores of the Mediterranean, including a visit to Algiers, Egypt, Palestine, Tyre, Rhodes, Telmessus, Cyprus and Greece, in two volumes, was an account of this journey: ‘Nothing can exceed the variety and incongruity of costume and the appearance of the people you meet with in the narrow streets of Algiers.’ It is hard, reading it, not to remember his son Oscar’s account in a letter to Robert Ross of a similar visit almost sixty years later with Lord Alfred Douglas, just months before his downfall: ‘There is a great deal of beauty here,’ Oscar Wilde wrote. ‘The Kabyle boys are quite lovely. At first we had some difficulty procuring a proper civilised guide. But now it is all right and Bosie and I have taken to haschish [sic]: it is quite exquisite: three puffs of smoke and then peace and love.’

William Wilde had interests other than peace and love. His son’s frivolity as revealed in his letters was matched by the father’s earnestness. William was fascinated by the diverse ethnicities, religions and traditions he came across, as well as the wildlife. On the ship he had a dolphin dragged on board and dissected it over three days, gathering material for a scientific paper. In Egypt, he made a close study of monuments, as his son would do, as a student, on a trip to Greece in 1877. William Wilde hired a boy to take him into underground Egyptian graves, affording him an opportunity to display both his vivid prose style and his intrepid spirit:

All was utter blackness; but Alee, who had left all his garments above, took me by the hand, and led me in a stooping posture some way amidst broken pots, sharp stones, and heaps of rubbish, that sunk under us at every step; then placing me on my face, at a particularly narrow part of the gallery, he assumed a similar snake-like posture himself, and by a vermicular motion, and keeping hold of his legs, I contrived to scramble through a burrow of sand and sharp bits of pottery, frequently scraping my back against the roof.

When he arrived at the burial place, ‘I do not think in all my travel I ever felt the same strong sensation of being in an enchanted place, so much as when led by this sinewy child of the desert through the dark winding passages and lonely vaults of this immense mausoleum.’

On his return to Dublin, William Wilde gave lectures on any subject that interested him, from anatomy to geology to archaeology to ethnology. He began to write for the Dublin University Magazine, whose editors included the lawyer Isaac Butt, who became a regular dinner guest at Wilde’s house in Westland Row, and the novelists Charles Lever and Sheridan Le Fanu. He also travelled to London and then to Vienna and Berlin to pursue his medical studies; he visited Prague, Munich and Brussels. In 1843 he published Austria, Its Literary, Scientific and Medical Institutions, and in 1849 a book on Jonathan Swift, The Closing Years of Dean Swift’s Life. He was also emerging as a famous doctor, specialising in diseases of the eye and ear, founding the first Eye and Ear Hospital in Dublin. In 1841, he was chosen by the Census Commission to find out more about the causes of death in Ireland. His Report upon the Tables of Death in the 1841 Census ran to 78 foolscap pages of closely written analysis, including a 94-item classification of diseases, using colloquial terms, Irish names and English translations, and then creating a standard system of description by which the diseases could be tabulated. He noted the many terms for scrofula that were commonly used in Ireland: ‘The Evil, King’s Evil, The Running Evil, Running Sore, Felloon, Bone Evil, Glandular Disease, an Impostume; in Irish Easbaidh bragadh, deficiency in the neck; Fiolun, the treacherous disease; Cneadh Cnaithneach, the wasting ulcer; Cuit bragach, cuts in the neck’. Analysing medical census returns, it is clear, required nuanced linguistic knowledge and sensitivity to local lore as much as statistical skills.

Wilde was a commissioner in Ireland for the 1851, 1861 and 1871 censuses. In preparing the questions for the 1851 census, his inclusion of questions about physical and mental handicaps was unique and original: such data had been gathered in no other country. When the returns for 1851 came in, Wilde wrote two of the volumes, more than seven hundred pages, and did not flinch from criticising the government for its policies on health and social welfare. He was appointed editor of the Dublin Quarterly Journal of Medical Science in 1846, and founded and ran St Mark’s Hospital in Dublin, one of the leading ophthalmic hospitals in the British Isles. He published the first significant textbook on aural surgery, Practical Observations on Aural Surgery and the Nature of Treatment of Diseases of the Ear, in 1853. The following year he published On the Physical, Moral and Social Condition of the Deaf and Dumb. A medical procedure – an aural incision – was named after him, and he was credited with developing the first dressing forceps as well as an aural snare called Wilde’s snare. He was the first to understand the importance of the middle ear in the genesis of aural infections.

But he was also becoming known as an important antiquarian, topographer, folklore collector and archaeologist at a time when the study of ancient Ireland was becoming politically resonant. He became friendly with George Petrie, who had done much to revitalise the antiquities committee of the Royal Irish Academy, and was responsible for its acquisition of important Irish manuscripts. Wilde worked with Petrie in County Meath, north of Dublin, discovering the remnants of lake-dwellings, known as crannogs, and recovering a large number of artefacts, which were put on display in the Royal Irish Academy. In his introduction to his book The Beauties of the Boyne, and Its Tributary, the Blackwater, published in 1849, Wilde wrote:

It may be regarded as a boast, but it is nevertheless incontrovertibly true, that the greatest amount of authentic Celtic history in the world, at present, is to be found in Ireland; nay more, we believe it cannot be gainsaid that no country in Europe, except the early kingdoms of Greece and Rome, possesses so much ancient written history as Ireland.

The Beauties of the Boyne, written shortly after the Great Irish Famine, is a meticulous guidebook, but at a time when the very name of Ireland carried a burden of poverty and misery, it also suggests that the Irish landscape possessed grandeur and nobility, and that the archaeology of the Boyne Valley offered resistance to any idea that Ireland could be easily integrated either spiritually or politically with England. The parliaments of the two countries had merged in 1800, but it was clear from Wilde’s book that the essential spirit of Ireland would remain implacably apart. That spirit was held in graves and churches and towers, signs in the landscape of a rich and complex life fully intact many centuries before the English efforts to civilise the country – so to speak – began:

It is very remarkable … how frequently we find some of the earliest Christian remains in the vicinity of pagan mounds, tumuli and other ancient structures, as if the feeling of veneration remained round the spot; and, though the grove of the Druid was replaced by the cashel of the Christian, still the place continued to be respected, and the followers of the early missionaries raised their churches and laid their bones in those localities hallowed by the dust or renowned by the prowess of their ancestors.

This idea of unstable and layered allegiances, of certain beliefs as a set of veneers, was something that would become an essential element in William Wilde’s own life, as well as the lives of his wife and his son. His Boyne Valley was a palimpsest of competing cultures. Near Navan, he finds a decaying castle, ‘marking the boundary of the English Pale: it tells of the worst days of misrule in this unhappy land, where, without conquering the proud hearts, or gaining the warm affections of the Irish, the Anglo-Norman barons, who, with mailed hearts as well as backs – neither civilising nor enriching the country – resided amongst us.’

It is clear that Wilde is aware of the difficulties inherent in any effort to describe the Irish landscape with political neutrality. Any reader in the aftermath of the Famine would be alert to the contemporary implications of his comment on the decaying castle. But he wants it both ways. In his preface, he writes like a loyal subject:

Her Majesty Queen Victoria, with her illustrious consort, has just visited this portion of her dominions, and by their coming amongst us, have done more to put down disaffection, and elicit the loyal feelings and affections of the Irish people, than armies thousands strong, fierce general officers, trading politicians, newspaper writers, and the suspension of the Habeas Corpus Act etc, etc. Let us hope that her welcome visit will be soon repeated.

One wonders what his wife-to-be would have made of his views on the queen and her illustrious consort. It’s possible that she would have understood perfectly the need for duplicity, or at least careful ambiguity, or seen the unease within the text as natural, part of the dual inheritance of the man she would marry two years after the book appeared.

William Wilde married Jane Elgee, a translator and poet, in 1851. She wrote for the radical, nationalist journal the Nation, and was also the true author of a fiery editorial – a revolutionary poem in prose – that had appeared in the paper in 1848. Isaac Butt, the lawyer defending the Nation’s editor from charges of sedition, pointed out that he couldn’t have written the editorial, since he was in prison at the time. When Jane tried to speak from the balcony to tell the court that she was the culprit, she was silenced, but Butt admitted to the judge that the editorial was the work of ‘one of the fair sex – not, perhaps, a very formidable opponent to the whole military power of Great Britain’. ‘I would not care to give pain to the highly respectable connections of this lady and to herself by placing her in the witness box,’ Butt went on, ‘but I ask the attorney-general, as a man of honour – and a man of honour I believe him to be – he knows the lady as well as I do – to contradict my statement if it is not true.’

Butt, who would feature prominently in the subsequent life of the Wildes, was two years older than William. He had studied at Trinity College Dublin, where Oscar Wilde would also be a student, and became a professor of political economy there and a lawyer. A staunch conservative, he opposed Daniel O’Connell’s campaign for the repeal of the Act of Union between Ireland and Great Britain, but his experiences in the Famine changed his politics, making him a Federalist rather than a Unionist. He later worked to defend various Irish revolutionaries, including the Young Ireland leaders and the leaders of the Fenian Rebellion of 1867, before becoming a member of the British Parliament, where he was the first to use the phrase ‘Home Rule’ to describe the need for political separation between Ireland and Britain. His name would appear twice in Joyce’s Ulysses and once in Finnegans Wake, and the bridge over the Liffey named after him was invoked in Ulysses.

But he also, it seems, had another connection to Jane Elgee before her marriage. In a letter to his son William in 1921, John Butler Yeats wrote of Jane Wilde: ‘When she was Miss Elgee, Mrs Butt found her with her husband when the circumstances were not doubtful, and told my mother about it.’ Butt enjoyed various romances, and was, on occasion, heckled at public meetings by the mothers of his illegitimate children – not unlike William Wilde, who by the time of his marriage had had two further illegitimate children, Emily and Mary, born in 1847 and 1849, who were taken care of as wards by William’s eldest brother, Ralph. (John Butler Yeats believed that the mother of these two girls kept a ‘black oak shop’ in Dublin.) William fully acknowledged his illegitimate son, known as Henry Wilson, who became a doctor, working closely with his father, and wrote the first book in English on ophthalmoscopy. Even at the height of Victoria’s rule, the Wildes and Butt were able to flout the rules of sexual morality, thanks in part to their gnarled allegiances.

William Wilde , Jane Elgee and Isaac Butt were eminent Victorians in Ireland. They lived at a time when Dublin had no parliament and when revolutionary fervour was ill-fated or half-hearted: part of a literary rather than a serious political culture. They were a strange, unruly ruling class, not accepted as fully Irish and not wealthy landowners either. Until they made connections (William as an antiquarian, Jane as a poet and translator, and Butt as a lawyer) with the Ireland of their time, they were oddly powerless. But once the connection was made, their power was considerable. To a large extent, they could do whatever they liked. William Wilde had no difficulty in accepting a knighthood in 1864 for his work on the medical implications of the census returns, and his wife, despite her efforts to be arrested in 1848, was happy to be known as Lady Wilde, and indeed was often referred to in this way by her son Oscar. The Wildes were Protestants in a mostly Catholic country, with family origins in England and Scotland rather than Ireland. Their loyalty was to a distant England, from which some of their power came; Wilde was surgeon oculist to the queen. But it was also to a distant Ireland, a dream place of traces and fragments, a country that might once more, with their assistance, materialise. Their sense of privilege and power derived from the very oppressor of the ancient culture that they both admired and studied. Their dual mandate allowed them to give good parties and caused them to be noticed and to be remembered. Lady Wilde was given to grandiloquence, telling a fellow poet: ‘You, and other poets, are content to express only your little soul in poetry. I express the soul of a great nation. Nothing less would content me, who am the acknowledged voice in poetry of all the people of Ireland.’

Many accounts were written of them entertaining in their house at number 1, Merrion Square. George Bernard Shaw remembered William Wilde ‘dressed in snuffy brown; and as he had the sort of skin that never looks clean, he produced a dramatic effect beside Lady Wilde (in full fig) of being, like Frederick the Great, Beyond Soap and Water, as his Nietzschean son was beyond Good and Evil.’ Harry Furniss wrote that ‘Lady Wilde, had she been cleaned up and plainly and rationally dressed, would have made a remarkably fine model of the Grand Dame, but with all her paint and tinsel and tawdry tragedy-queen get-up she was a walking burlesque of motherhood. Her husband resembled a monkey, a miserable-looking little creature, who apparently unshorn and unkempt, looked as if he had been rolling in the dust.’ W.B. Yeats saw that any understanding of who Oscar Wilde became had to take into account the mixture of formidable intelligence and unmoored strangeness exuded by his parents. ‘They were famous people,’ Yeats wrote, ‘and there [is] even a horrible folk story … that tells how Sir William Wilde [as an eye surgeon] took out the eyes of some man … and laid them upon a plate, intending to replace them in a moment, and how the eyes were eaten by a cat … The Wilde family was … dirty, untidy, daring … and very imaginative and learned.’

But these accounts were all written many years later: Shaw’s in 1930, Furniss’s in 1923, Yeats’s in 1922. Although they were easy to mock, the Wildes, like their son, took themselves seriously. As did others. These later accounts do not tally with contemporary accounts of the Wildes that show they were much respected and admired. In July 1857 the Swedish writer Lotten von Kraemer and her father, the governor of Uppsala, visited the Wildes. Although it was one o’clock, the butler let them know that Mrs Wilde was still in bed. When William Wilde appeared, Lotten von Kraemer noted that

the noble figure is slightly bowed, less by years than by ceaseless work … and his movements have a haste about them which at once conveys the impression that his time is most precious … He carries a small boy in his arm and holds another by the hand. His eyes rest on them with content. They are soon sent away to play, whereupon he gives us his undivided attention.

At the time of the Kraemer visit, when Oscar was nearly three, William Wilde was involved in cataloguing the holdings of the Royal Irish Academy. The project had foundered on a number of occasions and he had agreed to take it on alone. ‘Had I known the amount of physical and mental labour I was to go through when I undertook the Catalogue,’ he wrote in 1859, ‘I would not have considered it just to myself to have done it; for I may fairly say, that it has been done at the risk of my life.’ ‘My husband so brilliant to the world,’ Jane Wilde wrote in a letter,

envelops himself … in a black pall and is grave, stern, mournful and silent as the grave itself … when I ask him what could make him happy he answers death and yet the next hour if any excitement arouses him he will throw himself into the rush of life as if life were eternal here. His whole existence is one of unceasing mental activity.

But he also made connections with foreign scholars, and did it in considerable style. In September 1857 he invited ethnologists from the British Association for the Advancement of Science on a trip to the Aran Islands. Seventy of them were conveyed to the largest of the islands by a steam yacht chartered in Galway. Wilde led the scholars through the island, jumping over walls and climbing hills, using a small whistle to assemble them. On the evening of the second day, when they had sufficiently studied the ancient monuments, Wilde organised a banquet for the visitors within the walls of the pagan fortress of Dún Aengus, the most spectacular site on the island, which forms a semi-circle on the edge of a high cliff, with a sheer drop of almost a hundred metres to the Atlantic below. Among them were the poet Samuel Ferguson and the painter Frederick Burton.

The writer Martin Haverty, who was also among the company, wrote: ‘This was our culminating point of interest – the chief end and object of our pilgrimage … This was the Acropolis of Aran … the venerable ruin which Dr Petrie described as “the most magnificent barbaric monument now extant in Europe”.’ Haverty described the unpacking of hampers, the sherry, the ‘abundant’ dinner. ‘It was a glorious day,’ he wrote, ‘the sun being almost too warm, notwithstanding the ocean breeze which fanned us, and groups of the islanders looked on from crumbling ruins around.’ There were many speeches made, by the provost of Trinity College Dublin, by the French consul, by Wilde, who appealed to the islanders to protect the fort: ‘Remember, above all, that these were the works of your own kindred, long, long dead, that they tell a history of them which you should be proud of, that there is no other history of them than these walls, which are in your keeping.’ Once the speeches were done, according to Haverty, ‘a musician, with bagpipes, played some merry tunes, and the banquet of Dún Aengus terminated with an Irish jig, in which the French consul joined, con amore.’

Wilde was knighted in January 1864. At the ceremony in Dublin Castle, Jane Wilde wore, according to one of the newspapers, ‘a train and corsage of richest white satin, trimmed handsomely in scarlet velvet and gold cord, jupe, richest white, satin with bouillonnes of tulle, satin ruches and a magnificent tunic of real Brussels lace lappets: ornaments, diamonds’. William’s knighthood was widely welcomed. The Freeman’s Journal reported: ‘A more popular exercise of the vice-regal prerogative, nor one more acceptable to all classes in Ireland, could not possibly have been made, for no one of the medical profession has been more prominently before the public for the last twenty-five years in all useful and patriotic labours than Doctor (now Sir William) Wilde.’ Lady Wilde wrote to a friend that ‘so many dinners and invitations followed on our receiving the title to congratulate us that we have lived in a whirl of dissipation – now we are quiet – all the world has left town – and I begin to think of reawakening my soul.’

As these honours came, and all this dissipation, and as Sir William Wilde was at the height of his fame, he and Jane were already being pursued by a woman called Mary Travers, who had been one of his patients.* She was the daughter of Dr Robert Travers, professor in Medical Jurisprudence at Trinity College Dublin. In July 1854 Mary, aged 19, accompanied by her mother, came to his surgery saying that she had problems with her hearing. Wilde, because he knew her father, waived his fee.

Mary was isolated. Her two brothers had emigrated to Australia and she did not have a close relationship with her father, who was separated from her mother. Once her treatment had ended, she continued to see William Wilde, who gave her manuscripts to correct and oversaw her informal education by recommending books to her. Soon, they began to write to each other. He took her to public events, helped her financially and included her in family outings. The Wildes saw a great deal of her over the next few years; William took both Mary and his wife to the inaugural meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in 1859. At some stage afterwards, when Mary and Jane fell out, William wrote to her, seeking to make peace: ‘If Mrs Wilde asks you to dine, won’t you come and be as good friends as ever?’ She was invited to Christmas dinner with the Wildes in 1861.

It was clear, however, that William was growing tired of her. In March 1862 he paid her fare to Australia so that she could join her brothers. She got as far as Liverpool, but did not board the ship to Australia. Two months later, she did the same again. In June 1862, at the Wildes’ house on Merrion Square, she entered Jane’s bedroom unannounced. There was an argument between the two women, but it was not severe enough to prevent Mary planning to take the Wilde children on an outing a few days later. Jane later said, however, that Mary Travers did not dine with the Wildes again. Mary wrote to William: ‘I have come to the conclusion that both you and Mrs Wilde are of one mind with regard to me, and that is, to see which will insult me the most … to Mrs Wilde I owe no money; therefore I am not obliged to gulp down her insults … You will not be troubled by me again.’ She sent William a photograph, which Jane returned with a cold note: ‘Dear Miss Travers, Dr Wilde returns your photograph. Yours very truly, Jane Wilde.’ But Mary continued to write to William. When she drank a bottle of laudanum, William went with her to the apothecary to get an antidote and made sure that she took it. In July 1863, she had a journalist friend produce a death notice for her as though it were actually a real cutting from a newspaper and sent it to Jane, who was staying in a house the Wildes had acquired on the seafront in Bray south of Dublin. When Jane returned to Merrion Square with the children, Mary appeared there again, demanding attention. She was not going to go away.

And then she wrote a pamphlet. It was called Florence Boyle Price; or a Warning and signed ‘Speranza’, Jane Wilde’s pen name from her days at the Nation. It told the story of Dr Quilp and his wife. Dr Quilp had

a decidedly animal and sinister expression about his mouth, which was coarse and vulgar in the extreme, while his under-lip hung and protruded most unpleasantly. The upper part of his face did not redeem the lower part; his eyes were round and small – they were mean and prying and above all, they struck me as deficient in an expression I expected to find gracing a doctor’s countenance … Mrs Quilp was an odd sort of undomestic woman. She spent the greater portion of her life in bed and except on state occasions, she was never visible to visitors.

Mary had a thousand copies printed and sent them to the Wildes’ friends; copies flooded their letterbox, some forwarded by well-wishers, some dropped in anonymously. After William was knighted, Mary wrote to him demanding twenty pounds, adding: ‘You will see what will happen if you are not so prompt as usual.’ In April 1864, as Sir William was preparing to give a lecture at the Metropolitan Hall in Dublin called ‘Ireland Past and Present: The Land and the People’, the audience was met with five newsboys holding placards with the words: ‘Sir William Wilde and Speranza’. They were advertising the pamphlet with the help of a handbell from an auctioneer’s. Mary Travers sat in a cab close by watching proceedings. The fly-sheet of the pamphlets declared that ‘the writer parades Sir W. Wilde’s cowardice before the public.’ On other fly-sheets there were extracts from 17 of William’s letters to Mary, letters that suggested their relationship had moved beyond that normally associated with a doctor and his patient.

The following day the press devoted more space to the events outside the hall than to the contents of Sir William’s lecture. When Jane fled to Bray, Mary followed her there and had a boy deliver a copy of the pamphlet to every house in her street. Jane responded on 6 May by writing a letter to Mary’s father:

Sir – You may not be aware of the disreputable conduct of your daughter in Bray, where she consorts with all the low newspaper boys in the place, employing them to disseminate offensive placards, in which my name is given, and also tracts, in which she makes it appear that she has had an intrigue with Sir William Wilde. If she chooses to disgrace herself that is not my affair; but as her object in insulting me is the hope of extorting money, for which she has several times applied to Sir William Wilde, with threats of more annoyance if not given, I think it right to inform you that no threat or additional insult shall ever extort money for her from our hands. The wages of disgrace she has so basely treated for and demanded shall never be given to her.

When, three weeks later, Mary Travers saw this letter, she sued for libel, with Sir William as co-defendant, since he was responsible in law for any civil wrong committed by his wife. The Wildes decided not to settle, and the case opened on 12 December 1864, lasting six days. Among the lawyers representing Mary Travers was the Wildes’ old friend, the formidable Isaac Butt.

Mary’s most damaging allegation was that Sir William Wilde, while treating her for a burn mark on her neck in his surgery in October 1862, had given her chloroform and had raped her while she was unconscious. ‘He came over,’ she told the court,

and took off my bonnet and then put his hand to pass over it [the burn] as he had often done before and in doing so he fastened his hand roughly between the ribbon that was on my neck and my throat and I in some way, I suppose, resisted; I believe I said ‘Oh, you are suffocating me,’ and he said, ‘Yes I will, I will suffocate you, I cannot help it,’ and then I do not recollect anything more until he was dashing water on my face … I had lost consciousness before the water was flung in my face; I did not see him throwing the water, but I felt it on my face; he said to me to ‘look up’, because that if I did not rouse myself I would be his ruin and my own.

Isaac Butt asked Mary: ‘Are you now able to state from anything you have observed or know, whether, in the interval of unconsciousness you have described, your person was violated?’ Mary answered: ‘Yes.’ Butt asked: ‘Was it?’ Mary again answered: ‘Yes.’

Sections from the letters between Mary and Sir William were read out to the court. They seemed to be regularly falling out and making up again. He sent her money and sometimes clothes. She snubbed him on the street and he wrote to remonstrate, always wanting to see her. Their relationship appeared to consist of having little arguments and difficulties and then making up again. Lady Wilde agreed to go into the witness box, but Sir William did not; Butt accused him of being cowardly and sheltering behind his wife. He cross-examined Lady Wilde for half a day, as she displayed lofty indifference to the whole matter of her husband’s relationship to Mary Travers. Butt even tried to raise the matter of the immoral tone of a book she had once translated, only to be stopped by the judge. Much as her son would later do when he was in the dock, Lady Wilde did not help her case by trying to make jokes. Referring to the mock death notice which Mary had sent her, she said: ‘I think I saw her next in August 1863 – after her death.’

The judge, in his summing up, said it was strange that Mary had never reported the alleged rape to anyone and even more extraordinary that, within a day or two, she was ‘receiving letters from him, receiving dresses from him’. A jury might conclude, he said, that ‘if intercourse existed at all, it was with her consent, or certainly not against her consent … and that the whole thing is a fabrication.’ The jury, after several hours’ deliberation, decided that Mary Travers had been libelled by Lady Wilde. The court set damages at a farthing, but the Wildes were responsible for costs, which amounted to two thousand pounds, more than a hundred thousand pounds in today’s money.

In Reading Gaol , the regime was not as severe as it had been in Pentonville and Wandsworth, where Oscar Wilde had spent the first months of his imprisonment. He no longer had to do hard manual labour; he was assigned work in the garden and put in charge of bringing books to other prisoners. While he took enormous exception to Colonel Isaacson, the prison’s governor during the early part of his stay, stating, with his usual flair for phrasing, that the Colonel had ‘the eyes of a ferret, the body of an ape, and the soul of a rat’, he grew to admire his successor, Major Nelson, who was in charge when he wrote De Profundis in his cell.

That Sunday afternoon, as I kept reading from De Profundis, I did not check the time or take a break. I tried not to stumble over the Greek words with which Wilde had peppered the text. The tone moved from the ruminative, the speculative to the most intimate and confessional and private. It was hard not to imagine Wilde lying back on his plank bed and realising that there were certain things about his life and the life of his family that Lord Alfred Douglas did not know and did not need to know. It is impossible to imagine that he returned to Merrion Square in December 1864 from his school in County Fermanagh for his Christmas holidays, at the age of ten, and did not hear about what had happened in court in the weeks before.

What is remarkable is how many connections there are between the case of Mary Travers versus Lady Wilde and the case Oscar Wilde took against the Marquess of Queensberry. First, there was the frenetic, almost manic activity of Travers and Queensberry, both of whom sought in public and in private to embarrass and harass the famous Sir William and Oscar Wilde. The image of Mary Travers outside the lecture that Sir William was to give is close to the image of the Marquess of Queensberry attempting to disrupt the opening night of The Importance of Being Earnest in 1895. Both wished to use a grand, ceremonious occasion for maximum dramatic effect. Both Travers and Queensberry left written accusations for everyone to read, the former a pamphlet, the latter a card at Oscar Wilde’s club with the words ‘Oscar Wilde posing as a somdomite’ written on it. Both controversies centred on a long and turbulent sexual relationship between one of the Wildes and a younger person. Both included a libel action. In both cases, the lawyer for the other side was someone the Wildes knew. (Oscar Wilde had been at Trinity College Dublin with Edward Carson, who represented the Marquess of Queensberry. ‘No doubt he will perform his task with all the added bitterness of an old friend,’ Wilde said when he heard that Carson was to take the brief.) Both Butt and Carson, ambitious men who later became influential politicians, attempted to use a book to suggest to the jury that the witness’s morals were suspect, the first a novel translated by Lady Wilde, the second The Picture of Dorian Grey, written by her son. Both Lady Wilde and her son made jokes and attempted a lofty tone in the witness box, which did not help their case. In both cases, the main focus of the trial, Sir William Wilde and his son Oscar, had two young sons who were away at school as the court proceedings took place.

But there was a great difference in the outcomes. In an editorial on Christmas Eve 1864, the Irish correspondent of the Lancet wrote:

Sir William Wilde has to congratulate himself that he has passed through an ordeal supported by the sympathies of the entire mass of his professional brethren in this city; that he has been acquitted of a charge as disgraceful as it was unexpected, even without having to stoop to the painful necessity of contradicting it upon oath in the witness box.

Lady Wilde wrote to a friend to say that ‘Miss Travers is half mad,’ and the case

was very annoying, but of course no one believed her story – all Dublin now calls on us to offer their sympathy and all the medical profession here and in London have sent letters expressing their disbelief of the, in fact, impossible charge.

The Travers court case did not seem to affect the lives of the Wildes in any obvious way. In May 1865 they were invited to the Lord Mayor’s ball to meet the Prince of Wales on his visit to Dublin. In May 1870 Sir William was among the distinguished and varied group who attended a meeting addressed by Isaac Butt to consider the forming of a Home Government Association in Ireland. And in 1873 he received the Cunningham Gold Medal from the Royal Irish Academy, its highest honour.

He had also, in 1867, published Lough Corrib, Its Shores and Islands, his most relaxed and engaging book, after travelling by steamboat along the shores of the lake and meticulously studying the landscape, always happy to speculate about real locations for legendary events. Close to Inishmain Abbey he unearthed a perfectly solid structure formed of undressed stone with openings, like crypts, cut into it. ‘These crypts are certainly the most remarkable and inexplicable structures that have yet been discovered in Ireland. At top they are formed somewhat like the roof of a high-pitched Gothic church, with long stone ribs or rafters abutting upon a low side wall.’ Underneath the passage is a footnote: ‘Subsequent to its discovery by the author and his son Oscar, in August 1866, and after Mr Wakeman had taken drawings of it, the Earl of Dunraven had a very perfect photograph taken of the western face of this structure.’ In the main text, Wilde resumes his speculation about the function of the building: ‘Possibly it may have been a prison, or penitentiary, in which some of the refractory brethren of the neighbouring abbey were confined.’ There is also an illustration included in the book of an enclosure on an artificial island on Lough Mask, which Sir William Wilde says is ‘by Master Wilde’.

Oscar Wilde was 11 then, almost 12, and would have been on holiday from school. This picture of him wandering on a remote island in the west of Ireland with his father seeking out ancient buildings that had not been noticed or charted, and making drawings, is a new version of him, far away from the London he eventually moved to: from the parties and gatherings, the witticisms (‘Nature: a place where birds fly around uncooked’), the cosmopolitan jibes (‘Grass is hard and lumpy and damp, and full of dreadful black insects’). Oscar Wilde knew about grass and birds. In August 1876, on holiday from Oxford, he wrote to his friend Reginald Harding, beginning the letter ‘Dear Kitten’:

Frank Miles and I came down here last week and have had a very royal time of it sailing. We are at the top of Lough Corrib, which if you refer to your geography, you will find to be a lake thirty miles long, ten broad and situated among the most romantic scenery in Ireland.

On 28 August, he wrote to William Ward from Illaunroe Lodge, Connemara:

I have only got one salmon as yet but have had heaps of sea trout which give great play. I have not had a blank day yet. Grouse are few but I have got a lot of hares so have had a capital time of it. I hope next year you and ‘The Kitten’ will come and stay a ‘lunar’ month with me. I am sure you would like this wild mountainous country close to the Atlantic and teeming with sport of all kinds. It is in every way magnificent and makes me years younger than actual history records.

Sir William Wilde had died in April, at the age of 61. Crowds attended his funeral: even Isaac Butt was among the mourners. His fortune was by now much depleted. Lady Wilde wrote to Oscar: ‘How are we all to live? It is all a muddle. My opinion is that all that is coming to us will be swallowed up in our borrowings before we are paid.’ On 16 June 1877, Oscar wrote to his friend Harding: ‘I am very much down in spirits and depressed. A cousin of ours to whom we were all very attached has just died – quite suddenly from some chill caught riding. I dined with him on Saturday and he was dead on Wednesday.’ The cousin was in fact Henry Wilson, William Wilde’s first illegitimate child. In his will Wilson left most of his money to the hospital his father had founded, and where he had worked, and left Willie Wilde, Oscar’s brother, £8000; he left Oscar only £100. ‘He was, poor fellow, bigotedly intolerant of the Catholics,’ Oscar wrote, ‘and, seeing me “on the brink”, struck me out of his will.’ Wilde also inherited Henry Wilson’s share of their father’s fishing lodge at Illaunroe, on condition that he did not become a Catholic for five years. The following summer he wrote a letter from Illaunroe to a Jesuit priest: ‘I am resting here in the mountains – great peace and quiet everywhere – and hope to send you a sonnet as a result.’ That seems to be the last time he went there. In 1881, to keep his life in London going, Wilde mortgaged the property and three years later he sold it.

But before he arrived in London, while he was still at Oxford seeking an archaeological studentship, he wrote to the professor of comparative philology: ‘I think it would suit me very well – as I have done a good deal of travelling already and from my boyhood have been accustomed, through my father, to visiting and reporting on ancient sites, taking rubbings and measurements and all techniques of ordinary open-air archaeologia. It is a subject of intense interest to me.’ In this letter, and in the letters he wrote from Illaunroe in the summer after his father’s death, we can catch a glimpse of what Oscar Wilde received from his father: a shadow path for him, a path that, as he sought fame in England, he did not follow.

There is a word his father uses twice in his Lough Corrib book, to describe a type of ornamentation: ‘fleur-de-lis’. He first uses it to describe the decoration on some tombstones he had uncovered at Annadown, and later in a description of two tomb flags at Cong. The word, strangely, slips and moves and makes its way into the letter Oscar Wilde wrote in his cell thirty years later. The year before Wilde was imprisoned, Lord Alfred Douglas had written a ballad called ‘Jonquil and Fleur-de-Lys’. In the poem, two boys meet: one a shepherd, the other the son of a king. In a mild homoerotic game they decide to switch identities:

And after that they did devise

For mirth and sport, that each should wear

The other’s clothes, and in this guise

Make play each other’s parts to bear.

Whereon they stripped off all their clothes,

And when they stood up in the sun,

They were as like as one white rose

On one green stalk, to another one.

When Douglas learned that Wilde was to be declared bankrupt, he sent him a message which, in the presence of the warder, was conveyed to Wilde in a low voice by a solicitor’s clerk: ‘Prince Fleur de Lys wishes to be remembered to you.’ In De Profundis, Wilde wrote:

I stared at him. He repeated the message again. I did not know what he meant. ‘The gentleman is abroad at present,’ he added mysteriously. It all flashed across me, and I remember that, for the first and last time in my entire prison life, I laughed. In that laugh was all the scorn of the world. Prince Fleur de Lys! I saw – and subsequent events showed me that I rightly saw – that nothing that had happened had made you realise a single thing.

The person who wrote these words in the early months of 1897 was acutely conscious that the difference between him and Lord Alfred Douglas was not only that he was incarcerated and Douglas was free, and that he was bankrupt and Douglas was living on his inheritance, but that they came from different worlds: the Queensberrys from a long line of English and Scottish lords, the Wildes from a place of their own invention, from reading and writing, from a close engagement with the fate of Ireland, from pure eccentricity and tireless work.

In the dim light of his cell, nearly 120 years after he wrote De Profundis, as I came to the end of my reading, it was hard not to feel awe at the idea of how far he had come, what dark knowledge he had gained, and how much he understood – as his father had understood too after his court case – that the only way he could rescue himself was by writing. In this cell each day, Oscar Wilde was busy, as his parents had been, finding the right words. He was working, finishing the letter so that it could be handed back to him as he emerged into daylight on 19 May 1897.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.