Centenaries are strange institutions, often with complex purposes, but this year’s commemorations of the Bolshevik Revolution – now thankfully nearing their end – have been in the West wonderfully simple-minded. How could it matter, after all, that a failed state calling itself socialist, its last paroxysm almost three decades behind us, began in revolution one hundred years ago? How is the passing of a century meant to alter anything? Most people in the West distrusted and feared the long-gone phenomenon (me too, as a lifetime anti-Leninist). Can’t we let it go? Even if some of us think that the failed state, in all its strangeness and monstrosity, did represent some kind of rare, maybe unique, breach in the otherwise impregnable order of capitalism – simply the memory of revolutionary surrender, for instance, Trotsky signing at Brest-Litovsk with a cunning of reason smile, is enough to go on making the Bolsheviks a bad object – how can we possibly imagine that now is a necessary moment to take stock of it? The moment we live in … the Red Army in the light of Islamic State? Stalin shadowed by Xi Jinping? The Civil War replayed on the oilfields of Kirkuk? Trump as a yet more disgusting Rasputin?

The timeframe that has mattered most in the year’s celebrations is not the century, but the years gone by since the Fall of the Wall. If the best way to make sense of the seventy years of the Soviet Union may be as an episode – a destabilising interim – in the order of warring nation-states, then a comparison with Napoleon inevitably crops up. How well, we might ask, roughly thirty years after Waterloo, had ‘Europe’ succeeded in managing the memory of the French Revolution and Empire? Intellectually, even given the freakishness of the first attempts (Thiers and Carlyle in the vanguard), the signs of an ongoing genuine effort to engage with past discontinuity – to recognise it, to struggle with the mixture of untruth and possibility it represented – were then unmistakable. Michelet’s great Histoire de la Révolution française was on its way to publication; in Germany the Young Hegelians were decoding the implications of their master’s post-Revolutionary Philosophy of Right; 1848 was approaching. The foundering of our own long moment of Restoration – the decades following 1989, the age of the one superpower, the love affair with resurrected Russia, the years when the words ‘Islamism’ and ‘populism’ disturbed no one’s sleep – has yet to produce a remotely comparable change of understanding.

For these reasons and more, I have been trying to forget the shows in London commemorating the Bolsheviks, in particular the Royal Academy’s Revolution: Russian Art 1917-32. But I haven’t been able to: some things, some spaces and images, have stuck in the mind like shards of glass. In particular, I’ve found myself from time to time back in a small dark room at the end of the Royal Academy’s exhibition, on the walls of which were projected mugshots of entrants to the Gulag. The room was manipulative, and I was manipulated like everyone else. This is not a comment on the efforts of Memorial, the research organisation whose work in the archives has given faces and life histories to the Terror statistics, and whose material was put to use here, but on the way the Royal Academy deployed it. There would have been a kind of obscenity in trying to resist. The faces flashing up a few feet away in the darkness – dazed, brave, brutalised, distraught, ironic, bitter, disbelieving, already not quite of this world, accepting or resisting their fate (some of them no doubt still ‘in the name of the revolution’) – demanded an answer, and seemed to know that no answer would be good enough. Certainly not that given by 2017.

It was also too close to obscenity that someone like me – a scot-free Western Marxist, faithful reader of Boris Souvarine and Victor Serge and E.H. Carr – should find himself waiting in the Memorial room for the ‘great’ victims, the Mandelstams, the Florenskys, the Kamenevs, the Bukharins, to appear alongside the entirely, uniquely ordinary ones. It was the ordinariness and uniqueness that mattered, I agreed with Memorial, the political fact the faces insisted on. I still think so. But I couldn’t escape my own history, and when the face of Zinoviev appeared for a minute I found myself trying, ludicrously, to read an ‘attitude’ into its sleepless and three-quarters-dead stare. I wanted then, and certainly afterwards, to forget the stare, and replace Zinoviev’s picture completely and finally with that of the woman hygienist from Siberia (I think I remember this right) who came up next. But it was hard. It wasn’t until several months later, when I plucked up the courage to see the British Library’s dreadful Russian Revolution: Hope, Tragedy, Myths, that I found the snapshot of Zinoviev I needed to purge the one taken by his killers. Here he was, on a squalid White propaganda poster from the early 1920s captioned Vozmezdie (‘retribution’), teetering on a cliff edge over the pit of hell, his name inscribed on the ground next to his feet, his ‘Jewish’ features (and rather nice suit) insisted on. Satan looked up from a few feet below, welcoming a fellow-traveller. Zinoviev, to remind you, was one of only two members of the Bolshevik Central Committee to vote against armed revolt in October 1917 – on entirely orthodox Marxist grounds. He resigned from the committee a few weeks later, after the shaky victory in St Petersburg, over the question of negotiations with the wider ‘trade-unionist’ working class. He thought them necessary, Lenin did not. (He was back on board with the party by the following March, and saw Petrograd through the abyss of Civil War.) The cliff edge of hell, in other words, was something Zinoviev lived on for most of his life. That’s where Marxists of his stripe thought we all lived. These days we are told (usually with a smirk) that he, unlike the majority of Old Bolsheviks led to the slaughter, faced the executioner’s bullet in 1936 entirely without dignity. Good for him.

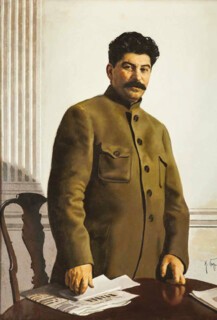

The Royal Academy’s Memorial room determined my memory of the show as a whole. (It was the visitor’s final stop before the souvenir shop.) But it wouldn’t have stayed with me in the way it did without its having been in some sense answered – goaded and parodied and maybe at moments genuinely contradicted – by other moments and images in the galleries leading to the last. I choose four from the many, because, like them or loathe them, I find them indelible. A painting by Izaak Brodsky of Stalin, done in 1928. A brief sequence from Eisenstein’s The General Line (begun the year before Brodsky, but re-edited frantically as the ‘line’ changed), in which the faces of peasants are splashed orgasmically by cream from a kolkhoz’s milk separator. A strange and electric painting by Alexander Deineka from 1926 – my examples cluster in the late 1920s, but the difference between 1926 and 1928 is already enormous – entitled Construction of New Workshops. And, fourth, the other pivotal space in the show, in painful tension with Memorial: the re-created ‘Malevich room’ from the exhibition 15 Years of Artists of the Russian Soviet Republic mounted in Leningrad in 1932.

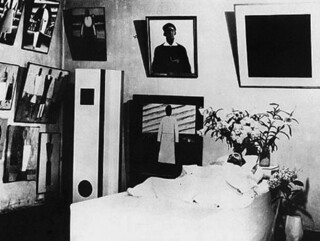

Inevitably, the reassembled Malevich installation had too much the appearance of a theme park, clean and well lit – the publicity photos don’t get that wrong. For those of us who had fed for years on the grainy black and whites of the exhibit taken in 1932, the weird warm glow of reality came as a shock. But the room was nonetheless a triumph, a reopened tomb, a definitive counterfactual – in which all the absurd and horrifying improbability of Bolshevik culture came back to outflank the mind. It reminded one, for a start, of the utter unlikelihood of the exhibit’s having happened in the first place, in the last grisly year of the first Five Year Plan. This is not what Stalinist art was (or is) supposed to have looked like. Malevich himself was suspect at the time: he had been recalled from his travels in Western Europe in 1927 and arrested and interrogated three years later. Friends had burned his papers. By 1932 he was poverty-stricken. I doubt we shall ever know the inside story of his being given a room to himself in Leningrad, but it clearly depended in part on the efforts of his friend and supporter Nikolai Punin, who was one of the curators of 15 Years. In a nearby gallery at the Royal Academy there was a wonderful mad portrait of Punin painted by Malevich in 1933, the critic hieratic in Piero della Francesca profile, kitted out in a sporty Suprematist dressing-gown and fez. The picture is signed bottom left with Malevich’s black square. (Punin’s other portrait in the show was saved for the Memorial cube. He died in the Gulag a few months after Stalin. No doubt his enthusiasm for Malevich was a small item on the torturer’s chargesheet.) But the fact that Punin had his way in 1932 – that he dared to try – should make us step back from our usual understanding of art in the moment before the Terror.

Not that I am claiming to understand what the Malevich room may have meant to its first audience, or what the artist intended it to mean. For that is the point. Bolshevik culture – the full range of possibilities and improbabilities released by the effort to end bourgeois society, even this late in the descent of that effort into hell – time and again brings on vertigo. Let me offer, for example, the text on the wall at the Royal Academy that tried to orient the visitor to the Malevich room: specifically, the answer it gave to the exhibit’s main enigma: the fact that the small core of abstract paintings Malevich chose to show in 1932, most of them dated from 15 years or more previously – the time of war and revolution – were flanked by depictions of men and women and landscape, the majority brand new compositions, their colour and form unmistakably claiming a continuity with the work from pre-1917:

Complex Suprematist canvases are exhibited here with Malevich’s later, more figurative paintings, in which blank faces hauntingly evoke lost identity on the collective farm. They were Malevich’s attempt to conform to the Soviet dogma that required art to be representational.

It would be foolish to overreact. But the questions are obvious. Why, for a start, if these were Malevich’s intentions, did he range the new canvases alongside the earlier ‘non-representational’ ones? Is it correct to characterise the faces in the new work – some of them by the look of it belonging to kolkhozniks, but others to athletes or schoolchildren or new ‘individuals’ presented in undifferentiated portrait space – as blank? Why do we think blankness ‘evokes lost identity’? This sounds bad to us – but did it to Malevich? As it happens, we have a letter from the same moment, April 1932, in which Malevich explains himself, in his own fashion. It is addressed to Meyerhold, the great director – another exhausted face that flashes up in the Memorial chamber:

I heard you were planning to build a new theatre with the stage in the middle. If this is true, it suggests to me that your ideas remain stuck on the same Constructivist treadmill … Painting has turned back from the non-objective path towards the object … But on the way back, painting came across a new object that the proletarian revolution had brought into being, and which had to be given form … Painting is the plane on which the two-dimensional and frontal articulation of this object will take place … You once destroyed the footlights (and I co-operated with you when we worked on Mayakovsky’s Mystery Bouffe), but now we have to stop all that, reinstall the footlights, and place the new objects and content in front of them.

‘Reinstall the footlights.’ Not the least of the provocations in the 1932 room was, and still is, the presiding presence, hung above the trio of complex abstractions on the middle wall, of two canvases containing nothing but a black and red square. The red square – actually a trapezoid, with its top right corner visibly impatient with symmetry – had been shown first in 1915. Its original title was Painterly Realism of a Peasant Woman in Two Dimensions. I am assuming, though I don’t know for sure, that the claim to peasant realism (Malevich’s earliest ambitious paintings had been of woodcutters and women coming from the well) was reiterated in the label on the wall in 1932.

The black square to the left – Malevich’s deepest mystery – had also first appeared in the wartime exhibition, hung in the high ‘icon corner’ of the gallery in Marsovo Polye, and the square had superintended all of Malevich’s efforts thereafter. The one displayed 17 years later was a duplicate, painted for the occasion. What, in 1932, did Malevich think the black square signified? It was, for him and his followers, undoubtedly (proudly) a shape – an abyss, a reality – that had prophesied 1917. That was why they believed it was capable of being filled with, but also exceeding, the ‘content’ of the epoch October had inaugurated. The black square was Bolshevism; but Bolshevism, they thought, if it was to become fully itself, had to agree to disappear into Suprematism’s gravitational collapse. ‘If materialism were content to build scaffolding on which to ascend to the nebulae and transform itself into so much mist in the turning of the great cosmic vortex – well, that would be a point in its favour, in my view; but as long as it presents itself as simply engaged in a “struggle for survival” or a struggle with Nature, all its victories strike me as meaningless.’ (Thus Malevich in 1920, in the thick of Civil War.) ‘Communism is already non-objective. Its problem is to make consciousness non-objective, to free the world from the attempts of men to grasp it as their own possession … Here’s where the new religion finds its international limit, the signs of which lie in Leninism, not Lenin.’ (Malevich in 1924.)

The struggle for ‘Lenin’, in the year of his death, was one Malevich seems to have thought he might win. Here is Art News reporting from Moscow in April 1924, on a competition held the previous month: ‘Malevich, who, like all other Bolshevik artists, has been working to express the greatness of Lenin in a model for his monument, proudly exhibited a huge pedestal composed of a mass of agricultural and industrial tools and machinery. On top of the pile was the “figure” of Lenin – a simple cube without insignia.’ Needless to say, the cube riding on a sea of hammers and sickles did not impress the judges. Perhaps, among other simpler objections, they sensed that the solid was meant to be deathly – death-dealing. ‘Communism is already non-objective.’ War and starvation are necessarily part of it (by 1924 Malevich knew both first-hand). The question remained: was death what ‘Leninism’ would turn out to be, in essence; and if so, death into what kind of life to come? When he fell ill in 1935 Malevich took meticulous care to stage the scene of his own death, and in the famous photos he made sure were taken of it – him lying in state next to his Suprematist coffin – the black square again presides. But the square remains in dialogue, on the death chamber’s side walls and even adjacent to the icon itself, with the ‘object that the proletarian revolution had brought into being’: women in the fields, a peasant face with a fleet of aeroplanes swooping over the kolkhoz furrows, ‘blank’ faces. The words ‘prototype of a new image’ are inscribed on the back of one of the anti-portraits.

Because the Malevich room in the Royal Academy reminded me of the depth of the artist’s engagement with Bolshevism, and because it seems to me duplicitous to shuffle that give and take offstage, does not mean I admire the give and take, exactly. Or that I find its key terms comprehensible. The black square is a mystery, and so are the last paintings hung next to it. If one wants an image of the black square in action, in ‘revolution’ – doing the work Malevich and his adepts seem truly to have thought it capable of – then the one I offer is a photograph that surfaced a few years ago, apparently showing the Red Army on pause, maybe bivouacking, in a forest. Experts I’ve asked about the photo have so far been guarded (I’d welcome further help), but the best guess seems to be that it was taken in 1920, perhaps on the front in the war with Poland. Malevich and his followers then had a foothold for their operations in Vitebsk. The black square in the photo is held aloft by soldiers in the middle distance. There are many words on the accompanying banners, most of them hard to read. Maybe this isn’t an army on the move – the reed platforms are odd – but some kind of propaganda gathering. The black square on its pole tallies with a reminiscence of the architect Lubetkin, who said he saw the squares, black and red, being carried as a kind of totem – first elements in a language starting to be speakable – in the Vitebsk streets. In any case, what seems to me to matter most in the photo is again the sheer unlikelihood of the square’s appearance – in a realm, for a purpose, whose co-ordinates we shall probably never know. And this is ‘Bolshevism and the avant-garde’ as I conceive it: an episode, a sideshow, a tragedy, in a history whose real dimensions still baffle. The room in 1932 goes with the icon in the forest.

Malevich is hard to stop writing about. Partly this is because of the man’s impenetrable life and character, but mainly, I think, because of his work’s authority. None of the mysteries and ironies attached to him would matter if the paintings on the walls did not look down on us with such unique naive power. For those who would like to detach that authority from the dialogue with Leninism, let alone from the catastrophe of collectivisation, there are many get-outs. ‘Form is form’ is an undying one. Or there is the Izaak Brodsky answer: look again at Brodsky’s 1928 portrait of Stalin, which was certainly one of the most brilliant and fully realised works in the Royal Academy show, as appalling and persuasive as Ingres toadying to Napoleon. And don’t artists invariably bow down to tyrants? Wasn’t Duchamp right when he said that the main problem for artists in bourgeois society was that at least in the age of autocracies patrons had been ‘aussi sots, mais moins nombreux’? Are not the black-cube Lenin of 1924, and the later promise to put the proletariat before the footlights, just two more versions of what pageant masters (providers of visual services) always say and do?

I don’t think so. I don’t think the charge of simple time-serving comes close to capturing what we see taking place, in the choice of works Malevich made for his 1932 exhibit, and the decisions about how they were to be hung. It doesn’t begin to get us on terms with what Malevich and Punin seem to have believed was at stake in the installation, the risks they were prepared to take to build it. Nonetheless, there is one further possible explanation for Malevich’s enthusiasm for collectivised man, which in its way is more damning than the one offered previously: namely, sheer bloody ignorance of what was happening in the countryside and party conclaves, combined with total certainty about what ought to be happening – the curse (as always) of the chattering classes. This charge might stick. I doubt we shall ever know how much or little Malevich and his circle knew or cared about the detail of Stalinism. (This marks them off from men like Rodchenko, who knew and concealed too much.) But it is a reverse kind of smugness simply to assume that for such as Malevich the kolkhoz – to say nothing of the fights within and beyond the party to define the limits of collectivisation, and the means of its implementation – was just another apocalyptic image, projected on the screen of ‘October’. The novels and memoirs of Victor Serge, for example, in their very sobriety a clue to conversations happening among friends, late at night in the kitchens of communal apartments, give a clue to the energy devoted, all through the 1920s and 1930s, to deciphering the hieroglyphs of Pravda. Platonov’s great novels (The Foundation Pit was being finished in 1930) tell the story of the horror – but also the elation and absurdity – of the new order. Of course the novels were unpublishable, and put Platonov in danger, but they speak to a horizon of knowledge – guesswork, first-hand testimony, reports finding their way to Moscow through the long channels of imprisonment and exile – that wasn’t Platonov’s alone. Certainly many people knew that collectivisation, and the drive to liquidate the kulaks, existed in a field of lies and inner-party skulduggery. Malevich, writing to an Old Bolshevik friend called Kirill Shutko in 1930 (Shutko was by then a high-up in the Central Committee’s Film Propaganda Section; what happened to him in the Terror I have not been able to discover), throws out the insult: ‘Soon the Brodskys will declare we are kulaks.’ The contempt for Brodsky is no surprise – Malevich wouldn’t have shared my high/low opinion of the Stalin portrait – but the confidence that Shutko would understand (and sympathise with) the duplicity of the ‘kulak’ charge is interesting. The accusation of political ignorance, in other words, as regards the making of the ‘new object’ – of not caring enough, of not wanting to know what the black square actually stood for in the early 1930s – will never go away, for Malevich and many others. But Platonov remains our guide. What was known – and much was known, or suspected, or glimpsed through the scrim of deceit – exceeded any one frame of understanding. We may draw back from Malevich’s certainty that the frame was his to provide (to Shutko again: ‘Before me stands a huge task … and I live in hope that Soviet Power in the person of Many Comrades will give me the chance to pursue it’), but the idea that out of the chaos of collectivisation might still emerge a ‘new object’ needing to be represented was not, in 1932, simply self-delusion.

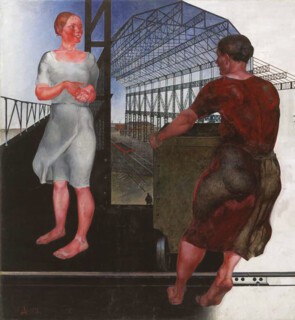

I realise that this last form of words offers cold comfort, and no doubt has a ‘Western Marxist’ flavour to it. But I stand by it – I think it is true to the tortured reality – and turn finally to Deineka and Eisenstein for support. Not that either the painting or the film sequence – Construction of New Workshops or The General Line’s ‘peasant’ faces laughing in the cataract of cream – escapes from the cliff edge. It is open to anyone (again, me too) to recoil from the woman with the handcart, or the old man chortling in the cream-flow, with something close to terminal impatience. Aren’t smiling muscled women factory hands, and earthy rambunctious cynical beautiful peasants, clichés – irredeemable bourgeois daydreams? (‘Une tache de populace/Les brunit comme un sein d’hier;/Le dos de ces Mains est la place/Qu’en baisa tout Révolté fier!’) Isn’t the very identity ‘peasant’ – restricting ourselves to that monster – a fiction that obscures almost everything? And wasn’t this obscuring part of the tragedy that Eisenstein’s comedy covered up?

It seems so. But I think we are wrestling here with limits – blindnesses – built into any class society (and not even the most addled party member thought ‘Socialism in One Country’ was anything else). Both Eisenstein and Deineka knew they were working with images, ciphers, into which, inevitably slowly and against the grain, new content might be introduced. It is hard to give a fair assessment of Eisenstein’s achievement in The General Line as a whole, because the film was immediately butchered by the commissars (and of course that butchery, that sense of the commissariat being one’s first and pre-eminent audience, is part of the story, not an aside). So I turn to Deineka in 1926.

It would be nice to know what Malevich made of Construction of New Workshops. Probably not much. But evidently Deineka had looked long and hard at Suprematism – even his signature seems to have a little of the Master about it, and the black and red coal trolley right at the painting’s centre is taken straight from a UNOVIS poster. Deineka is trying for something new (if one thinks of him in relation to the left and right brands of ‘new figuration’ being pursued at the time in Germany and Italy his uniqueness is clear). He seems to want an easy integration of modernist self-consciousness with a realist insistence on matter, manufacture – painting as work not ‘composition’. He manages it, I think; but one senses his isolation, the price he pays for making things up in what mostly remained a void. (Plenty of talk in Moscow and Leningrad about the outlines of a socialist realism with a Cubist face: precious few examples.)

Deineka was represented at the Royal Academy by several other extraordinary things: a science fiction Textile Workers from 1927, all whites and blue-greys; a Mexican-mural-type Defence of Petrograd; stamped-out schematic pictures of runners and soccer players, one of them done as late as 1932. It is sad (though understandable) that paintings of this kind seem to have had no progeny. Sometimes Deineka’s acknowledgments of surface and workmanship in Construction of New Workshops are too heavily signposted: the girders becoming an unfinished grid mid-right, for instance, or the railway lines changing colour from white to black, lifting into Suprematist lines of force. Maybe the worker in silhouette next to the handcart is too clever – too eager to speak to socialism’s scale. But the excesses are surely the price paid for the painting’s wonders: the entirely original coexistence of ‘flat’ shape and sculpted solid in the woman with the handcart; the astonished hands of her interlocutor; the ballet of bare feet; the naivety of distances; the flickering of the rail on the ground nearest to us (and the ground itself, under the women’s feet) between materiality and abstraction.

Writing about painting often circles around what truly characterises the image it is trying to describe. My last paragraph is no exception. It is easier to talk about devices and structures than to specify expression and purpose. And of course what counts finally in Deineka’s Construction is what the construction releases: its temper, its ‘characters’, their expressions and form of life. The woman in white is the carrier of that form. That many viewers will find her expression – her eagerness and optimism, her entire vulnerability – absurd, even unforgivable, is part of the point. For she is the ghost of the Soviet Union.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.