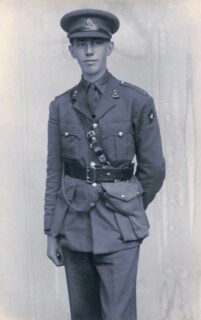

The war rescued my father, Peter Raban, from his first job as a probationary teacher in the West Midlands and restored him to his proper station as an officer and a gentleman. He had hoped to go on to university (Oxford or Cambridge) from his boarding school in Worcester but his dismal Higher School Certificate results nixed that ambition. He went instead to King Alfred’s, a teacher training college in Winchester, where (as he would point out more than fifty years later) he was the only student to have been educated at a (minor) public school, and in June 1938, when he was 19 going on 20, he graduated with a certificate that qualified him to teach in state-funded elementary schools.

Tall, beanpole-thin, with dark skin and a shock of coal-black hair, shy and socially awkward, my father returned home to the village of Hadzor in Worcestershire, just outside Droitwich Spa, to spend the summer hunting for a job within commuting distance of his father’s rectory. Some time in the 19th century the Church Commissioners had combined Hadzor and its equally small neighbour Oddingley into a single parish, so that although he had fewer than two hundred parishioners in all, my grandfather had two ancient churches to maintain and at least two Big Houses, Oddingley Grange and Hadzor House, whose owners would expect deference from their local clergyman.

My father wanted to find a job in Droitwich or Worcester, but the only position he was offered was at Colley Lane School in Cradley Heath, a town in the industrial Black Country west of Birmingham – a twenty-mile train ride from Droitwich that took him into an alien world for which he was totally unprepared. Disraeli had once described Cradley Heath as the ‘Hell Hole of England’, and the town earned a chapter to itself in an 1897 book on women’s sweated labour, Robert Harborough Sherard’s White Slaves of England. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, Cradley Heath was known as the world’s capital of hand-hammered chain-making, and boasted, somewhat weirdly, that the anchor chain of the Titanic had been manufactured there. It was an improvised, ad hoc town of steepling factory chimneys, coalmines with gibbet-like scaffolds for their winding gear, and a tangle of streets lined with terraced hovels, many of them with a furnace in the backyard or in a side room of the hovel, where men and women melted the iron rods that they hammered into chains and continually rehydrated themselves with beer at threepence a quart. Pay, at best, was tuppence-halfpenny an hour. Sherard described it as a ‘terribly ugly and depressing town’.

By the time my father arrived in 1938, it had grown even more ugly and rundown during the Great Depression. Mechanisation had all but killed manual chain-making, and most of the coal pits had fallen into disuse. Unemployment figures were so high, even in that era of mass unemployment, that a question was asked in Parliament about the crisis in Cradley Heath. My father had never seen anything like it, and it terrified him. This industrial slum on the further outskirts of Birmingham was beyond his comprehension. At Colley Lane School, he lost control of his class. The children never stopped mocking his lah-di-dah accent, and he found their Black Country dialect perfectly impenetrable. In the staffroom, he was little better off. In a letter written to my mother at the end of the war he would describe himself as ‘an out-and-out Conservative’; his colleagues at Colley Lane were, with good reason, solid Labour Party supporters, and he made no friends among them. In another 1945 letter, he described his time at the school as a ‘year of bitterness and hell that I shall never forget’.

Between the ‘peace in our time’ euphoria that Neville Chamberlain brought back from Munich in September 1938 and Hitler’s invasion of Czechoslovakia in March 1939, the British public reluctantly came to realise that war with Germany would soon break out, and my father jumped at the chance of escape from Colley Lane and the prospect of a new life. At his boarding school in Worcester he had been more successful in the Officers’ Training Corps than he was in his School Certificate: he had passed the two-part military test called Cert. A, the basic requirement for being considered for a commission. He went about getting one in the old-fashioned way, by visiting the Big House, Oddingley Grange on Trench Lane, whose châtelaine was a Mrs White, aunt of Lieutenant-Colonel Philip Robinson, commanding officer of the Royal Artillery 67th Field Regiment, Territorial Army. Lt Col Robinson approved, and a gruff handshake transformed my father into a second lieutenant, though he had to serve his time as a failed schoolteacher until June 1939.

By the time my father enlisted, the British government was scrambling to put the country on a war footing. In March 1939, the Territorials were doubled in size to 440,000 men. In April, conscription was introduced for 20 and 21-year-old males to go on a six-month military training course, and on the day Britain declared war on Germany, 3 September, the call-up was extended to able-bodied men between the ages of 18 and 41. Tented camps across the country filled up with civilians learning to be soldiers, my father among them.

His best subject at school had been maths; he had a knack for carrying sums in his head which made him a natural candidate for the Royal Artillery, and he possessed his own slide rule (when he returned from the war at the end of 1945, this instrument became for me an object of occult veneration). Calculation of range and trajectory came easily to him as he practised lobbing 18-pound shells from Mark I field guns left over from the Great War.

The regiment left Worcester in the summer of 1939 to camp out near Lyndhurst in Hampshire, then moved in the autumn to Aldbourne in Wiltshire, on the edge of Salisbury Plain. Both were conventionally picturesque places: Lyndhurst was in the middle of the New Forest, and wild ponies often wandered into the streets; Aldbourne was an unspoiled village with the usual accoutrements of church, five pubs, cottages, a green, a duck pond and a purling stream. It might be nice to think that the War Office picked these locations to provide the young recruits with fresh memories of the peaceful and bucolic country they’d be fighting for, but the nearby artillery ranges in both places were the more likely draw.

At Aldbourne the troops learned that in January they would set sail for France, where they’d become part of the British Expeditionary Force, which had been assembling across the Channel since the declaration of war. Because of the imminence of their departure, the 67th Regiment was granted an extended home leave for Christmas. My father and one other officer volunteered to remain in Aldbourne over the holiday to guard the fort while the other soldiers went home. This saved him from the annual embarrassment of having to choose whether to spend Christmas in Lancashire with his mother – she had walked out on the family and returned to her hometown of Oldham nine years earlier – or at the rectory with his father.

He had another, perhaps more powerful and certainly more consequential, reason to stay on in Aldbourne. He had been invited to a formal dinner dance at a flash hotel in Newbury, 15 miles from the village. The party was to celebrate the engagement between my mother’s brother, Peter Sandison, and Connie Major, both in their final year at Birmingham University. My Uncle Peter, as he would become, was due to join the Royal Navy as a lieutenant on his graduation in June. The war and mass enlistment had already caused a shortage of available men, and my father, who was no dancer, was dragged in to play the role of my mother’s partner. He took the bus to Newbury in full dress uniform, with highly polished Sam Browne belt (the polishing done by Gunner Tench, his batman), riding boots and spurs – he removed the spurs for ‘the dancing’ to avoid inflicting serious injuries around the floor.

The event, as he wrote more than fifty years later, was his introduction to a milieu more ‘sophisticated’ and ‘cosmopolitan’ than anything he had experienced before, and he was overawed by the company he was keeping that evening. He and my mother, Monica Sandison, had met at the Grange, where she sometimes went riding with Mrs White’s daughter Barbara, and they had made occasional trips to the pictures in Droitwich and Worcester in my mother’s second-hand Humber. They were still more acquaintances than friends, having never held hands, let alone kissed: their first kiss would happen nearly a year after Newbury. But my parents-to-be had much in common, as yet unearthed, especially the unhappy secret of being children in disintegrating and disintegrated marriages.

On 11 January, after he had made whirlwind visits to his parents at Oldham and Hadzor, my father sailed from Southampton aboard one of two requisitioned passenger steamers, escorted by Royal Navy destroyers, on an overnight crossing to Le Havre. It was his first time abroad, and everything about France was novel in his Worcestershire eyes.

This was still the period of the Phoney War, when Britain and France waited for the Nazis to mount an invasion by land or sea and their spies were producing a multitude of conflicting intelligence reports. In England, every day brought false alarms, with the urgent high-low-high-low screaming of air-raid sirens, shortly followed by the sustained note of the All Clear. People were enjoined to carry their boxed gas masks with them everywhere, and the dusk-to-dawn blackout was punctiliously enforced by civilian wardens, causing an abrupt rise in traffic fatalities. But the most conspicuous feature of the Phoney War was the havoc caused by the ‘evacuees’ from the big cities: several million school-age children, along with pregnant women and mothers with their under-fives, who were bundled onto trains and sent out into the countryside in the first four days of September 1939. This chaos, born of bureaucratic panic and a gross overestimation of the likely casualties of German bombing raids, was called Operation Pied Piper, and it plays a central part in Evelyn Waugh’s seriocomic novel of the Phoney War, Put Out More Flags.

A photograph from the period, taken in Le Mans, nicely catches the mood. Two teams are playing football. One side (clearly the Brits) is clad in stripped-down battledress, and the other (presumably French) is in dark shorts and white jerseys. The only spectators we can see are a cluster of British soldiers, one of whom stands behind a single anti-aircraft gun mounted on a flimsy looking tripod. He seems to have his eyes on the game, not the sky. Anything might happen. A Bren gun is there just in case. There’s a war on, but nobody on the field appears to believe it, and the poor gunner must have been the butt of everybody’s jokes. The short magazine above the narrow barrel looks as if it holds barely enough rounds to bring down a pheasant, let alone a German bomber.

The 67th Field Regiment, and all its trucks, guns and supplies, disembarked at Le Havre and set up camp at a village nearby, where they reassembled with their weapons. No doubt they made plans with the French for a series of football matches to strengthen their alliance. My father was not a football man. He had always played rugby at school and despised football as a game suitable only for the working class. He was, however, a competent player of contract bridge and a keen reader of Ely Culbertson’s bridge books. A regular four, including my father, whiled away evenings in the officers’ mess playing for low stakes (five shillings was a win worth noting in my father’s diary, as was a loss of two shillings and sixpence).

He was a member of A Troop, 265 Battery. His troop commander was Captain Jimmy Styles. The usual complement of officers in a Royal Artillery troop at that time was a captain and two subalterns, but my father fails to mention the second subaltern in his troop (the equivalent of a platoon in an infantry regiment). Maybe there was one or maybe A Troop was an officer short – I can’t tell.

The phoneyness of the Phoney War in Western Europe was due to the extreme reluctance of all sides to be the first to kill civilians on their home ground (though Germany showed no such compunction when it came to bombing Polish civilians on its eastern front). Enemy shipping, both naval and merchant, was fair game for the British, French and German air forces and navies, though when the RAF sent flights of bombers over German cities they dropped many tons of propaganda pamphlets but no bombs. The first British civilian to be killed at home in the war was an Orkney islander who died in a Luftwaffe raid on the naval base at Scapa Flow on 16 March 1940. Three days later, the RAF retaliated by sending fifty bombers to destroy the German seaplane base at Hörnum in the Frisian islands, a raid that lasted from 8 p.m. to 3 a.m. on the night of 19-20 March. An officer at the briefing described the atmosphere as ‘charged with anticipation and excitement at the prospect that we were going to drop bombs and not those “bloody leaflets”’. The press called the attack a triumph (vast damage in raf raid was the headline in the Australian paper the Argus), but aerial reconnaissance the next day showed the base had escaped with hardly a scratch. The Air Ministry announced that their photos of Hörnum after the raid were of too poor quality to be released.

In Normandy, A Troop went out on training exercises (my father, fast becoming proficient in military terminology and slang, always called them ‘schemes’), was treated to lectures on gas warfare and did regular gas drills – an indication of just how closely the Second World War was expected to follow the pattern of the First, and of how misguided that assumption would turn out to be. It took the British far too long to learn that Blitzkrieg was an entirely different kettle of fish from the long, slow war of attrition they had fought between 1914 and 1918. The 66,000 casualties that the BEF would suffer between 10 May and 25 June were a measure of their disastrous failure to grasp what it was that they were facing.

No doubt the bridge four steadily improved their game as they got to know one another’s bidding habits and foibles. Monica Sandison wrote at least two letters to my father at this time, but there was no particular intimacy in them because she was responding to a War Office campaign encouraging women in England to write to servicemen overseas. My mother was an enthusiastic writer of letters and probably sent dozens to male acquaintances across the length and breadth of France.

Warfare and tourism are less often linked than they should be. For my father, as for so many of his fellow soldiers, this was his first chance to experience the continuous cascade of new sensations that drenches the stranger who sets foot for the first time in a foreign country: the exotic morning smell of baking bread from the boulangerie as it mingles with the smoke of Gauloises and Gitanes; the surprising styles of architecture, shop fronts and street furniture; the unfamiliar dress; the non-stop mental arithmetic as one translates prices in francs into pounds, shillings and pence – everything, in its strangeness, insists on attention being paid all at once. The soldier is a tourist, not just in every moment he has to himself but in all the other moments when he’s meant to be concentrating on something else. How many have died because they became distracted by an oddly coloured bird, a zigzag moulding around the doorway of a nearby church, a woman wearing a burqa, the impenetrable calligraphy of a foreign road sign?

The main concentration of troops was in north-eastern France towards the Belgian border, the same area that the British, French and Germans had turned into a welter of mud and blood in the dreadful 1914-18 war. So the 67th Regiment set out for battlegrounds that were grimly vivid in the memories and nightmares of the older men. In an unending military convoy (the average speed to aim at was 12.5 mph) trucks carrying soldiers and towing field guns, policed by motorcycle outriders (of whom I believe my father was one), wound through the lanes of agricultural France. The soldiers looked out on a land far less crowded than their own; its fields and woods bigger, its villages smaller. Army trucks are made for singing songs and telling dirty jokes and stories. From the trucks came ragged choruses of voices going through the repertoire of songs from the previous war: ‘Mademoiselle from Armentières, parlay-voo?’, ‘When this lousy war is over’, ‘We are Fred Karno’s army’, ‘Oh, oh, oh, it’s a lovely war’. The view from the back of each jolting truck held the eye by its inalienable Frenchness: rectangular yellow letterboxes instead of the red pillar boxes of England; pissoirs that exposed the trousers and shoes of the men peeing in them; a dead-straight road lined with hundred-foot poplars just coming into leaf.

The man-boys know they are immortal; death has no place on their agenda, even though the guns, mounted on limbers that their trucks are towing, all have their barrels trained on the truck behind. When darkness falls, the convoy slows to a crawl, each truck relying on a single headlamp, hooded, veiled and tilted sharply down. The drivers crane forward, noses to the windscreen, as they try to make out the road ahead and the blocky outline of the gun and limber immediately in front.

Crossing the Somme, the convoy entered the territory of mass graves commemorating the fallen of the Great War in the gently rolling countryside of the old Western Front. At least some of the defiantly cheery songbirds in the convoy must have felt a twinge of foreboding as their trucks passed the enormous cemeteries. Here we go again – another four years in the trenches? What no one could have imagined was how quickly and humiliatingly they were going to be outmanoeuvred, outpaced and defeated by the Germans.

The convoy found its destination at the drab coalmining village of Evin-Malmaison, twenty miles from the Belgian border. There was still as yet no sign of German troops moving west, though they were expected any day now. The 67th Field Regiment continued to mount daily gas drills, and was ordered to rehearse a new task: digging and building gun pits. One advantage of a regiment of weekend soldiers is that the great majority of them have expertise in their weekday professions. So when builders, ditch-diggers, bricklayers and other workers in the construction industry were told to step forward, an entire skilled labour force emerged from the ranks. The army manual on gun pits was passed around, and the men set to work. When Major General Watson, the commander of the Royal Artillery, saw what the 67th Regiment was doing, he summoned the colonels of all the other artillery regiments so that they could observe how the job should be done – at least so says the regimental history.

The armies massing on the Belgian border – a sea of slightly different shades of khaki (French uniforms were greener) – brought a huge temporary boom to the local economy. Everything that could be eaten, drunk, smoked or sent home as souvenirs vanished from restaurant tables and shop shelves. The soldiers, in the hyper-acquisitive mood that arises from boredom and nervous anxiety, spent as heavily as many of them had ever spent before. The Anglo-French football games persisted and so did the rubbers of bridge in the British officers’ messes. The second bottle of wine, the third double Scotch, became the daily habit. All this paralysed inactivity made the ennui thicken like curdling milk in the French air.

All artillery units in the BEF were ordered back to the Somme for practice on the ranges there, probably because doing something was better than doing nothing at all. The gunnery practice lasted less than two days: on 10 May they were hastily recalled to the border as news broke that Germany was invading the Netherlands, Luxembourg and Belgium. The Royal Artillery scrambled to rejoin the flood of troops pouring across the Belgian border, and raced to take up its preplanned defensive positions east of Brussels along the River Dyle as it meanders northwards between the towns of Wavre and Leuven – a distance of barely twenty miles as the crow flies, but much longer if you take the meanders into consideration. The BEF, under Lord Gort, was much the smallest of the three national armies, Belgian, French and British, that were defending the west bank of the Dyle, with Belgians to the north, French to the south, and British sandwiched in the middle. My father’s regiment set up its HQ in the village of Leefdaal, a couple of miles west of the river, which is modest, shallow and in some places hardly wider than an English 18th-century canal. Between the village and the river there is a wooded area, more ridge than hill, that rises about 250 feet above the water, where, I guess, 265 and 266 Batteries set up their guns to await the arrival of the German tanks and infantry.

According to my father’s later notes, the elderly 18-pounders had a range of only nine thousand yards, just over five miles, which meant that the enemy had to be too close for comfort before they became a reachable target. Having hastily settled their guns into position on the evening of 12 May, A Troop wouldn’t actually fire them until 15 May, leaving them more time than they wanted to digest the shocking news that Germany had hoodwinked them, and they had been caught in a trap Hitler set.

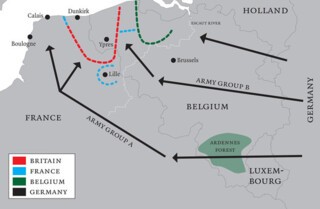

The Allies believed that in defending the River Dyle they were protecting western Belgium from the main thrust of the German advance, which they saw as a repetition of Germany’s invasion of Belgium in the early days of the First World War. This was exactly what Hitler meant them to think. In fact, the westerly advance of the Nazi troops was conducted by Army Group B (26 infantry and three armoured divisions), while the much larger Army Group A (38 infantry and seven armoured divisions) was secretly heading south into France through the Ardennes.

General Gamelin, now commander-in-chief of the French armies, though he would be relieved of his command later in the month, had once called the Ardennes ‘Europe’s best tank trap’ and a prewar French survey of the forest had found that, should Germany try to force their way through the Ardennes it would take them at least five days. The terrain was too rough, too steep, too thickly wooded to allow faster progress. But the German generals, warning their troops that they would have to forgo sleep for at least three nights running, had issued everyone with Pervitin tablets, a powerful methamphetamine and an early form of crystal meth. High and wide awake, the tank drivers crashed through the forest, hidden from aerial surveillance by the canopy of fresh leaves. Blitzkrieg required its fighters to be on meth, as Norman Ohler has shown in his book Blitzed: Drugs in Nazi Germany.* When on 12 May the panzer divisions emerged from the trees near Sedan on the River Meuse, they took the French utterly by surprise. Sedan was thinly defended, mostly by army reservists, and the river was crossed on the 13th. Beyond it lay many miles of undefended farmland. The tanks, fuelled as much on Pervitin as gasoline, sped on, leaving the marching infantry far behind.

The aim of this ‘sickle cut’ (Churchill’s phrase for it, later translated into German as Sichelschnitt) was to slice the Allied forces in two, occupy the Channel ports, surround the armies now in Belgium, and drive them into the sea. Rommel, who led the speediest of the tank divisions, was said to take Pervitin as if it were his daily bread. ‘He had no apparent sense of danger,’ Ohler writes, ‘a typical symptom of excessive methamphetamine consumption.’

The British, getting by on tea and Wild Woodbines (or in my father’s case St Bruno Flake pipe tobacco), were a poor match for the Germans on their army-issue uppers. At Leefdaal, the two gun batteries and the regimental HQ at last came under intense German shellfire on 14 May; Stukas dive-bombed the British artillery and strafed them with machine-guns. On the 15th, the German troops came close enough for the batteries’ World War One guns to fire at them, which they did in barrages of 100 shells per gun before they were ordered to retreat to Auderghem on the south-eastern outskirts of Brussels, where they were again in action until nine on the morning of the 16th, when they had to retreat again to the western side of the Brussels-Charleroi canal. Here they were heavily bombed yet again, and it was midnight when the order came to retreat to Aspelare, a hamlet a few miles west of Brussels.

According to the brief regimental history published in 1964, the regiment’s centenary year, ‘it was a nightmare move; all the Division was using the same road and traffic conditions were appalling. Exhausted drivers were continually falling asleep over the wheels of their trucks, helping to spread the confusion.’ It seems likely that the anonymous author of the history was present at the humiliating defeat he describes. His wild misspellings of nearly every place name in the account (Yvonne Mal Maison for Evin-Malmaison, for instance) suggest a state of battle-weary confusion. The regiment was dead on its feet after more than three days of continuous fighting and retreating, shellshocked by the noise of their own and enemy artillery, and terrorised by the Stuka dive-bombers’ Jericho Trumpets – propeller-driven sirens that wailed as they dived and were designed to spread panic far beyond their immediate targets. The Germans were euphoric and alert on crystal meth; the British, French and Belgians were stupefied zombies.

Somewhere between Leefdaal and Aspelare my father’s troop commander, Captain Jimmy Styles, was killed. That, and the fact that it was ‘near Brussels’, are all that my father mentions in his skimpy notes, and by the end of the sentence he has arrived at Dunkirk. There’s no mention of how he got along with Styles, no mention of how he was killed, or how long he took to die. Did A Troop dig a grave for his remains? Were other men killed or wounded in the attack? I think that when my father looked back on that long sequence of sleepless nights and days, all he could see was a distressing, phantasmagoric blur in which one fact was plain – not so much Jimmy Styles’s death, but how it had fallen to my father to keep the survivors in the troop alive.

Like so many of his generation, my father was taciturn about the war after his return home in 1945. I never heard him speak of it throughout my childhood and adolescence, and I was in my mid-twenties before he began to unbutton himself on the subject, mostly in light-hearted stories about, for example, how he’d returned to his billet in Northern Italy after a bibulous New Year party at a neighbouring officers’ mess, and fallen through the glass of somebody’s snow-covered greenhouse, his floppy drunkenness saving him from injury. But I watched as the line-up of histories of the Second World War grew longer and longer on his bookshelves. The war was a private matter, a secret to be kept between his older and his younger selves. The sheer incommunicability of actual warfare kept him silent. Siegfried Sassoon was eloquent about his time on leave in England and how it made him boil with anger. The Channel may be barely twenty miles across at its narrowest point, but the gulf between the meaning of war to a soldier in the trenches and the meaning of war to the English non-combatants, with their complacent talk of heroes and patriotism and pro patria mori, was oceanically unbridgeable even when the sound of the guns across the Channel became audible through the windows of Kent and Sussex. The flight to Dunkirk must have seemed like that to my father: inexplicable, unspeakable, a lonely, private nightmare.

Luckily there was another second lieutenant in my father’s regiment, whose memoir, written in 1946, of the retreat from Brussels to Dunkirk, bristles with closely observed contingent detail. E.J. Haywood, an intelligence officer answerable to the brigadier in whose car he travelled, was sufficiently detached from his regiment to take a broad view of the retreat. The brigadier is referred to throughout as ‘the Brig’; the general commanding the division is known as Bulgy and another junior officer is Puffer; Haywood himself acquires the nickname Big Bill, after Big Bill Haywood, the leader of the Industrial Workers of the World (the ‘Wobblies’). When Big Bill refers to a fellow subaltern as Crumpets I can hear his boarding school accent and catch his self-possession. He speaks both French and German well enough to make himself understood to the natives and captured invaders, and has about him a lightly worn, unselfconscious patriotism and pride in his regiment. He is also modestly knowledgeable about French wines, and he smokes a pipe. Except in that last, shared characteristic, he and my father seem like polar opposites: the one socially at ease, with sophisticated tastes; the other shy, self-conscious, fearful of saying or doing the wrong thing.

In his memoir, Haywood conjures the state of the roads leading south and west from Brussels in May 1940 as one catastrophic traffic jam, with three fleeing armies and their vehicles having to struggle for space with an equal number of civilian refugees headed in the same direction, in hooting cars, on bicycles, with horse-drawn carts laden with piles of hastily packed possessions, topped, as often as not, with a shawled grandparent too sick or lame to walk. Others trundled pushcarts, prams and wheelbarrows before them. Everyone in their mid-to-late twenties or older had first-hand memories of the earlier war in Flanders and its dreadful noise and destruction. Since 1918, the land had been patiently restored to a peaceful quilt of farms and repaired villages, punctuated by vast, well-tended military cemeteries. Now the whole horror appeared to be happening all over again. ‘Once that morning,’ Haywood wrote,

I saw German aircraft attacking refugees. A few planes flew up and down the road dropping bombs at will. They then returned, one after the other, flying low over the heads of their screaming victims, spraying them with machine-gun bullets. Our car was in the thick of it, but Jim yelled at the driver to keep going, and we were lucky. We saw people hit or blown to pieces; carts and cars burning or shattered; small children crouching in the ditches in a nightmare of terror; farm horses threshing in agony and making the road slippery with blood. I bounced about in the car, scared and angry, and, in futile rage, leaned out of the window and fired my revolver at the aircraft. It was the only time I ever fired it, and I wasted six bullets. Jim did not turn round, but shouted: ‘Use a r-rifle, you b-b-bloody fool!’ However, by the time I had got the driver’s rifle poking through the window, the raid was over.

The infantry brigade to which Haywood was attached had to march everywhere they went, often for 12 hours and more at a stretch, while the Brig’s car kept on falling back to pick up stragglers and look for lost soldiers sleeping in ditches. Frequently the Brig marched in step with his men to bolster their morale. The retreat soon fell into a pattern: each day would be spent trying to hold off the German advance westward with artillery and rifle fire; each night they’d fall back to take up new positions on the west bank of the next river. So the Senne was crossed, then the Dendre, then the Escaut, as the Franco-Belgian upper reaches of the Scheldt are called.

The Escaut is a major river that flows broad and deep from south to north, and here it was hoped by the Allies that the Germans would not just be temporarily deterred but stopped in their tracks. But this plan was jinxed by poor communications between the separate armies that too often depended on telephone lines that were all too easy to cut. Upstream of the British and Belgian positions, the French busied themselves with engineering an ‘inundation’ that would place a lake between their own troops and the Germans. The predictable effect of the French dam was that hour by hour the river shrank between its banks, and with every lowering of the water the Escaut became less and less of an obstacle to the German tank divisions, and after four days of heavy fighting, the Allies had to abandon the river.

The troops were now flat-out exhausted, hungry (on half-rations, then on whatever they could scavenge), dirty and smelling as rank as skunks. On narrow roads, clogged with marching infantry, vehicles of one kind or another, and hundreds of thousands of panicking refugees, the retreating armies, harassed by German shellfire and regular attacks from the air, were lucky if they could achieve walking pace for a few minutes at a time. Ceaselessly honking horns trumpeted their own futility.

The Pervitin-fuelled German Army Group A continued its advance into French territory, only temporarily held up by an Anglo-French counterattack at Arras on 21 May. On 22 May, the port of Boulogne was cut off, and the next day Calais was encircled. On 24 May, just before noon, with German tanks less than twenty miles from Dunkirk, a baffling order came from Hitler, acting on the advice of Colonel-General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commanding officer of Army Group A, saying that the tanks must stop where they were. This ‘Halt Order’ has been a subject of dispute ever since it was issued.

British Nazi sympathisers, like Henry Williamson, the author of Tarka the Otter, claimed that Hitler was showing friendship to his British ‘cousins’ by deliberately allowing their army to escape. Two facts stand in the way of this Compassionate-Führer theory. First, Dunkirk’s immediate hinterland was bad tank country: a boggy low-lying plain, riddled with canals, dykes and ditches, to which the French had added yet another ‘inundation’ by opening some of the dykes, thereby forcing many of the fleeing Allied troops to wade through waist-deep water. Second, Hitler had been persuaded by Göring, his Reichsminister of aviation, that Dunkirk would be best left as a wide-open target for the Luftwaffe. This would also serve to remind Hitler’s competing generals who their real commander-in-chief was. ‘We were utterly speechless,’ General Guderian, co-architect with General Erich von Manstein of Blitzkrieg as the new method of warfare, wrote of seeing the Halt Order. The order was rescinded two days after it was issued, but those 48 hours were an unexpected gift to the Allies, who used them to shore up Dunkirk’s defences and assemble their impromptu fleet of ships and small boats to rescue the troops.

I’ve lost my father in the long confusion of the retreat to Dunkirk, but he had clearly not lost himself. I looked for him in the Battle of Arras, where Second Lieutenant Haywood was promoted in the field to acting captain and adjutant of the 8th Battalion, but although several Royal Artillery regiments were involved, the 67th Field Regiment was not among them. My father next breaks cover, in his own account, on 1 June, on Dunkirk’s perimeter canal, where he and his troop were reunited with Major A.O. McCarthy, the battery commander, a regular army officer attached to the Territorials. A Troop’s guns were set up on the inside bank of the canal, from where they fired their last barrage until their supply of ammunition was exhausted. The troop then ‘spiked’ the guns, rendering them unusable, and left them where they stood, before clambering into and hanging onto the sides of the one remaining 8cwt truck that was in working order for the short ride to what little was left of the town.

Bad weather on 30 and 31 May had largely grounded the Luftwaffe, but 1 June was a day of clear blue skies and an air raid had just started when the truck arrived in the already bombed-out city. A Troop immediately took shelter in a basement. The remainder of the regiment were already on the beach, from where they would eventually be rescued by HMS Worcester. Photos taken in May 1940 show Dunkirk as a smouldering wreck: buildings ripped right open, fires blazing, an enormous plume of thick black smoke rising from the bombed oil refinery (the Luftwaffe did themselves no favours there); the only thing left apparently intact is the freestanding Gothic bell tower of St Eloi’s Church; at 190 feet it was – and is – a landmark visible from many miles around and across the soggy plains of the northern Pas de Calais. The Dunkirk beaches had turned into a vast rubbish dump of military vehicles and artillery pieces – tanks, trucks, cars, most of them set on fire with their radiators smashed and their engines left running so that they would soon seize up. Rifles and Bren guns were stacked in heaps, rucksacks scattered everywhere along the sands. The sea itself broke sluggishly and with difficulty under the weight of the enormous oil slick released by more than a hundred sunken ships, many of whose masts and funnels showed above the water. In that water, marbled with all the colours of the rainbow, floated the distended corpses of men and horses. The horses were another throwback to World War One: the French still used them for military transport. The air itself was foul, stinking of piss, shit, burning oil and the unattended dead. Meanwhile the troops waded in orderly columns up to their shoulders in the noxious sea, patiently waiting – often for hours on end – to be rescued. When Dunkirk survivors spoke of their experience long after the event, the most frequent word they used was ‘hell’, hell on earth, a living hell.

My father and his troop were extraordinarily lucky, at least in his own savagely abbreviated notes. As soon as the Luftwaffe raid was over, they were ordered to move at the double to a destroyer at the end of the narrow eastern breakwater (or mole). HMS Esk was about to cast off to answer a mayday call from a requisitioned passenger ship, the Scotia, which had been bombed in the raid and was sinking fast near No. 6 buoy with around two thousand French soldiers aboard. Since the Esk had only just arrived in Dunkirk during the raid, A Troop may have been the first and last British soldiers to embark on her.

The Esk’s rescue of the Scotia is well told by David Divine in The Nine Days of Dunkirk, first published in 1959. The ship had been hit ‘abaft the engine-room on the starboard side and on the poop deck, and in the final attack one bomb went down the after-funnel. Scotia was heavily damaged and began to sink by the stern, heeling steadily over to starboard.’ Divine then hands the narrative over to a written report by Captain Hughes, the master of the Scotia:

Commander Couch of HMS Esk had received our SOS. He was lying at Dunkirk at the time; he came full speed to the rescue. By now the boat deck starboard side was in the water and the vessel was still going over. He very skilfully put the bow of his ship close to the forecastle head, taking off a large number of troops and picking up hundreds out of the sea. Backing his ship out again, he came amidships on the starboard side, his stem being now against the boat deck, and continued to pick up survivors.

The Scotia had by now gone over until her forward funnel and mast were in the water. Two enemy bombers again approached us dropping their bombs and machine-gunning those swimming and clinging to wreckage. The Esk kept firing and drove the enemy away. Commander Couch again skilfully manoeuvred his ship around to the port side, the Scotia having gone over until the port bilge keel was out of the water. Hundreds of the soldiers were huddled on the bilge and some of them swam to the Esk, while others were pulled up by ropes and rafts.

Divine’s book is unusually interesting because he made three cross-Channel trips in a ‘stolen’ twin-screw Thames motor cruiser, ‘about 30-foot in length’, named White Wing, to pick up BEF survivors from Dunkirk, yet was quick to scotch the sentimental myth of the ‘little ships’, according to which Britons spontaneously came together, ditching all distinctions of wealth, rank and social class, and took to their boats – fishermen, bank clerks and patrician yachtsmen alike racing across the Channel to Dunkirk in order to save their stranded army. The ‘Dunkirk spirit’ became a favourite trope for Conservative politicians from Churchill to Thatcher, but there is little truth in it. Divine could have cast himself as an exemplary hero in this myth but instead he insists that the mass evacuation, known as Operation Dynamo, was in fact a hugely complex, if continuously improvised, naval exercise. Several photographs make it clear that most of the so-called little ships reached Dunkirk in rafts of several dozen at a time, all of them empty, many without their owners’ knowledge or permission, being towed by oceangoing tugs. The primary use of small boats in the evacuation was to ferry men in the shallows to the big, deep-drafted ships waiting just offshore. A very large number of boats were abandoned at sea because the soldiers who manned them were desperate to escape, and set the craft adrift as soon as the last man had climbed aboard the rescue ship. Used once, lost for ever. Signals sent from Dunkirk to Vice-Admiral Ramsay, in charge of the operation in Dover, show an inexhaustible hunger for more and more small boats.

The salvage of French troops from the sinking Scotia by a British destroyer came at a moment when everyone was blaming everyone else. The French blamed the British for again proving themselves to be Perfidious Albion. The British blamed the French for their poor morale and readiness to surrender to the Germans. British soldiers unjustly blamed the RAF for failing to protect them from the Luftwaffe. In one incident, a British army officer rescued a pilot who had parachuted to safety from his stricken Spitfire: the officer made him quickly change his RAF uniform for army battledress to save him from being beaten up, or worse, by his fellow countrymen. Even aboard the Scotia, Captain Hughes (who spoke no French) had to borrow a revolver (from a French officer) to restore order to his shipload of evacuees, but the Esk/Scotia episode was a seemingly rare case of international accord among the fractious and quarrelsome Allies.

My brother William tells me that our father once told him of the ‘ingratitude’ shown by a French officer whom he helped climb over the Esk’s rail from the scrambling net on the ship’s side. The frozen, waterlogged Frenchman, far from saying a word of thanks for my father’s assistance, let loose a tirade against the English, shouting that they were interested only in rescuing themselves while leaving the French to defend the Dunkirk perimeter and be taken prisoner by the Germans.

On the short voyage back to the English coast, the returning soldiers were sternly lectured on the need to remain silent about what they had seen in Dunkirk, for fear of the damage it could do to civilian morale. That silence enabled the myth of the ‘little ships’ to triumph over the story of what actually happened, which in itself was mythical enough. Nearly 340,000 soldiers were rescued from Dunkirk and its beaches. The troops themselves knew that they had been conclusively defeated by the far superior tactics of the Germans, and expected to be met at home with relieved but glum faces, as befitted a failed army. Their actual reception astonished them. Eloquent photographs show waving flags and cheering people crowding the bridges over the Dover-London line as trains packed with Dunkirk survivors pass under the arches. Dazed, sleepless, filthy but happy soldiers wave back from the train windows. The myth was working its magic.

Churchill, who had succeeded Chamberlain as prime minister on 10 May, the day the Phoney War ended and Hitler invaded the Low Countries, called Dunkirk ‘a miracle of deliverance’ in his speech to Parliament on 4 June, the last day of the evacuation, but acknowledged that the defeat of the BEF was a ‘colossal military disaster’ and that ‘wars are not won by evacuations.’ Churchill’s ‘miracle’ (Wunder in German) was also the word used by the Nazis to describe their lightning conquest of France, which formally surrendered on 22 June.

The Esk, after rescuing close to a thousand French troops from the Scotia, with HMS Worcester assisting (though she was badly bombed, and several soldiers on the Worcester’s open deck were killed or injured), sailed, unmolested by the Luftwaffe, to Dover, from where my father caught the train to Victoria Station. As an officer he was required by military regulations to travel first class, while Other Ranks were ordered into third-class compartments to avoid any undesirable ‘fraternisation’ between the officers and their men. (Second class had been abolished in the 19th century, but the numerical space, or no man’s land, between one and three helped, I suppose, to emphasise the gulf between the classes.) So the return to England from Dunkirk signalled – in case anyone had failed to notice – a return to strict social conformity.

Trying to keep track of my father and his troop as they move through this momentous sequence of events is like trying to keep one’s eyes on a single small fish in a vast migrating shoal of pilchards. Now you see it, now you don’t, and you never will again. Other people were watching him far more closely than I possibly can, and they noticed that he was cool under fire, shouldered responsibility when responsibility was thrust on him, spoke like a gentleman, and could play a decent hand at bridge. He was earmarked for early promotion.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.