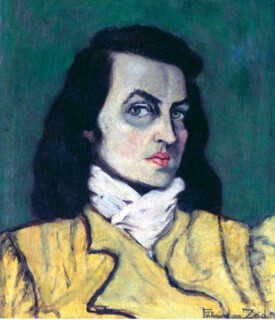

The centrepiece of the Fahrelnissa Zeid show at Tate Modern (until 8 October) is My Hell, a vast canvas – five metres across and two metres high – of swirling curves and broken triangles. It’s a diptych or possibly a triptych: yellows and blacks in the left section, blacks and reds to the right, arranged around a jagged absence close to the middle. The forms seem to accumulate at speed: large slabs of colour sit close to the edges, and then a regression of smaller shapes starts appearing in a rush of little pieces, intersecting black lines resolving into tiny tessellated fragments. The last time the picture was on view in Britain was in 1954, at the ICA, when Zeid – niece of a grand vizier of the Ottoman Empire and a Hashemite princess by marriage, the wife of the Iraqi ambassador to the Court of St James’s – was seen as being at the cutting edge of modern art. She couldn’t make it in New York, with Ab Ex at its height and fierce about foreign influence, but in London and Paris she was a painter to be reckoned with. Charles Estienne, a significant French critic, became her champion, and Tristan Tzara and Francis Picabia thought highly of her giant abstracts at the Musée d’Art Moderne. She painted My Hell in her studio on the third floor of the Iraqi ambassador’s residence: the canvas was tacked to the wall, floor to ceiling, travelling around the corner of the room, enveloping her. Writers who praised the ICA exhibit at the time – she was one of the first women artists to be shown there – didn’t see the need to mention her social connections, or make too much of the hybrid influences which the Tate et al now list in their descriptions: from Byzantine mosaics to Islamic stained glass to early Cretan art. Of course it didn’t hurt that she was a notable: there’s a photo of her receiving the queen outside St George’s Gallery in 1948, for her first solo exhibition in London – two grandes dames respectfully attended by a line of handbag-clutching royal watchers. But for contemporary reviewers, she was mostly just a very impressive painter.

She called it My Hell because some aspect of what she lived through was that. She seemed to have a fine time as the ambassador’s wife, meeting Matisse in Paris and summering on Ischia, and she didn’t mind the parties, but in 1950, when My Hell was painted, she had just seen her niece die from cancer, having held her hand through it all at the London Clinic, and this was just one of a weirdly large number of personal and family disasters she faced. She was born in 1901, on the island of Büyükada outside Istanbul, surrounded by inlaid mother-of-pearl furniture from Damascus passed on by her uncle, the grand vizier; the house had its own hammam, a large number of servants (including a Sudanese eunuch) and a grotto filled with geraniums and orchids tended by her father, a military officer and diplomat. When she was 12, the first disaster struck: her older brother, Cevat, took out a gun and shot their father dead. Nobody knew why it happened; Cevat got 14 years for manslaughter. Fahrelnissa adored her brother: it was he, she said, who had made her want to paint; at the age of four she would sit at his feet listening to the scratching of his quill while he drew portraits in black ink of the girls he was infatuated with. After their father’s death, with the family running low on money, Fahrelnissa, who was already drawing obsessively, started hand-painting postcards, selling them in a local shop in order to buy the brushes, paints and notebooks she needed. After leaving school, she refused to stay at home like her sisters and enrolled at Istanbul’s new School of Fine Art for Girls. When she was 19 she married her first husband, Izzet Melih Devrim, the president of the Imperial Tobacco Monopoly, because he promised to take her to visit museums in Europe. They attended grand balls, learned fashionable jazz dances, went swimming in the Bosphorus. Then disaster two: in 1923, their son Faruk died of scarlet fever at the age of two and a half. ‘I felt I was a tree whose branches were being hacked off with a big axe,’ she said years later. ‘The agony was nothing I have suffered before or since. I was immunised for life.’ But not immunised enough: the only form of therapy that worked for her was painting, which she started to do all day, shut away in the studio in their Istanbul flat.

You wouldn’t know it from the wall texts at the Tate, or from its generally very helpful catalogue, but depression was a recurring battle. A new biography by Adila Laïdi-Hanieh, a cultural historian who as a teenager was taught to paint by Zeid in Amman, documents consultations with the Austrian psychiatrist Hans Hoff, an overdose of sleeping pills, Zeid checking herself into hospital in Paris and, in 1939, taking refuge at the Gellért Hotel and another sanatorium in Budapest, away from her family, to try to pull herself together (Art/Books, £19.99). In Budapest she painted street scenes; she had been reading about Brueghel and all around her she saw his ‘swarming [grouillement], the unexpected attitudes, the physical malformations as well as the obsessive beings’; she would paint herself at the edge of the frame, a black silhouette on the outside looking in. These paintings from her pre-abstract period are all missing: they were stolen at Sofia train station as she made her way back home to Istanbul. Over the next few years she tried to remake them; in one of these re-creations, Budapest: View from the Express between Budapest and Istanbul (1943), included in the Tate catalogue though not in the exhibition, a group of Pierrot-like skaters dance over a blue-green frozen pond, with the movement all in the swirling figures; the buildings and bare trees beyond are static, the train the picture is seen from apparently stopped. Except the picture isn’t really seen from the train at all: at the lower edge, leaning against a balustrade, is a black-hatted observer, an image of the painter, the only one not joining the dance. There is something uncertain about the paintings from this period: in Third-Class Passengers (also 1943), colourful figures in turbans and abayas sit on the floor of a waiting room and eat or pray, but the patterns made by their twisting forms fight with the patterns of the multiple brightly coloured carpets they sit on. Subjects, background and decoration all compete for attention.

But then she hadn’t completely worked out what she wanted yet. It became clear gradually. In 1947 she painted Fight against Abstraction, a picture full of visual jokes: two raised fists confront each other, one pudgy and fleshy-grey, the other an assembly of stripes or ribbons. Behind them a Grecian profile of a man is built up out of stained-glass-like coloured fragments, his beard a sequence of green and purple triangles. She was at last letting the thick ink-black lines she had always played with – in sketches of Bedouin women, in calligraphic studies – cover the whole pictorial field. Her first fully abstract painting was Resolved Problems (1948), a patchwork of reds, greens, yellows and blues; she said air travel had helped her to see differently.

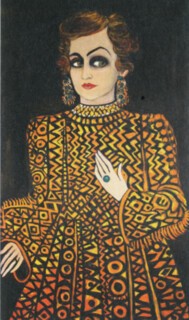

The years in which she made her best and most distinctive work, the late 1940s and the 1950s, were years when she was living in London – and spending time, too, in a studio she rented in Paris – with her second husband, the ambassador, Prince Zeid Al-Hussein, the younger brother of King Faisal I of Iraq. She was happy with her Arab prince, though things didn’t always go smoothly for him. His previous posting, to Berlin, was cut short after the Anschluss; Fahrelnissa hadn’t thought much of Hitler as a conversationalist, but being confined to Baghdad was worse. Europe was where she could see the things she was interested in, and it worked wonderfully for them, most of the time. As the current king of Iraq’s great-uncle, it was one of her husband’s jobs to act as regent every summer, while Faisal II went on holiday. In 1958, Fahrelnissa decided Prince Zeid had spent quite enough time at work in Baghdad, and persuaded him to join her on Ischia instead. It was a lucky call: that was the summer the Free Officers mounted a coup to overthrow the Iraqi government, killing Faisal II and most of his family and ending the rule of the Hashemite dynasty in Iraq. Prince Zeid would have been killed too, but he lost only his ambassadorship, which meant that on their return to London they were forced to move to a small flat, where, at the age of 57, Fahrelnissa cooked her own meal for the first time in her life. She was so intrigued by the bones from the chicken carcass after they had finished eating that she kept them and painted them, later covering them in polyester resin; she called her bone sculptures paléokrystalos, a word apparently of her own invention, and a few of them are on display at the Tate. When Prince Zeid died in Paris in 1970, Fahrelnissa was ‘completely broken’. She finally left Europe for good, and moved to Amman to be near her youngest son, Prince Raad, the head in exile of the royal houses of Syria and Iraq. In Jordan, where she presided over the art scene and introduced a generation of women to international art, among them her future biographer, she turned again to painting portraits: figures with huge eyes and enigmatic expressions, including the self-portrait Someone from the Past (1980), in which a younger Fahrelnissa, in a zigzag pattern dress, raises an eyebrow at the viewer and displays an elegant hand. She died in 1991, and was buried in Amman’s royal mausoleum next to her beloved prince.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.