Alberto Giacometti (b.1901) had his first postwar show in France at the Galerie Maeght in Paris in 1951. From 1941 to 1945, he had been stranded in his native Switzerland, working on tiny sculptures that he brought back to Paris – so the story goes – in matchboxes. He had started scaling up since then, creating the austere works in plaster and bronze for which he’s now remembered. By the time of the show the height of these figures, with their gaunt charisma, was going on for two metres. Giacometti had already made a name for himself before the war with the help of the Surrealists, but with his return to Paris, he entered a league of his own.

In a commission timed to coincide with the show, Francis Ponge, a poet with a sharp descriptive eye and a gift for comic analogy, was asked to write about Giacometti by Christian Zervos, the founder of Cahiers d’art. Ponge had lately tied himself in knots trying, and failing, to address the topic of ‘man’ in the ironic-methodical spirit he had brought to other ‘things’ in the world – oranges, rain, oysters – in his collection Le parti pris des choses. The two sensibilities – his and Giacometti’s – could not have been further apart, despite their friendship and their political sympathies: Ponge was a member of the Communist Party for ten years, Giacometti a fellow-traveller. Ponge found much to praise in Giacometti’s work; his evocation of a generic ‘man’, straitened and distended, may even have given Ponge the idea that he could start again, learning from Giacometti how to whittle this enormous subject down to within a millimetre of its armature. Yet in his notes for the essay, published in the 1960s, we see Ponge circling round the work with clusters of wordplay and bouts of throat-clearing, unable to come to the point, perhaps – and he’s not alone – because he didn’t know what to make of it.

Tate Modern’s Giacometti (until 10 September) is serenely sure of itself. The gallery has hosted him with a suite of ten rooms, beautifully lit, the work disposed with sympathy, even a kind of reverence, catching the measure of his doggedness and taking us with confidence through his career as a sculptor, painter, draughtsman and maker of ornaments – sweet, ingenious pieces – destined for the salon mantelshelf. The catalogue, with topics arranged in alphabetical order – A for androgyny, B for ballpoint, and so on through Z for Zervos – turns out to be an astute repurposing of browser culture: even a hurried listings reviewer will end up reading most of this book, darting from one bit to the next. Some of the best entries begin with S, for ‘sculpture’, ‘space’ and ‘Surrealism’.

Giacometti was surrounded by writers drawn like flies to his mortuary forms. I encountered his reputation in their essays long before I looked at his art in its own right and I still see it darkly at the far end of a corridor of brilliant commentary. There are many entries here for the writers who took up with him – Georges Bataille, Michel Leiris, Sartre and Beauvoir, Jean Genet and others – though none under B for Beckett, and none for John Berger, who was cool at first, then much warmer, coming under fire from David Sylvester – another S – for disparaging Giacometti’s work in the 1950s, and then for revising his opinion after the artist’s death in 1966.

The first room contains a superb display of heads, dating from Giacometti’s earliest years and on through his celebrity. Each has an eye on something, and even if they aren’t all looking our way, they are vigilant, a bit disarming. Beyond them space opens up, in the next room, then the next, through his Surrealist moment and on to the emaciated, fire-bombed figures, planted in their ample, airy settings. Around the walls of further rooms are the large paintings in muddy tones to which we turn for reassurance that a figure evolved in two dimensions can recover the human density drained from his sculpted works. A Giacometti statue addresses the medium in which it’s made (or cast) – clay, plaster, bronze – far more emphatically than the thin air (or is it light?) that it displaces as a finished object. It’s hard to tell what these pieces make of their surroundings in the first place. All we know is that they embody Giacometti’s energetic wish to dominate space by having them occupy less of it. Tate Modern is perfect for that. His passive-aggressive feminine forms, inquiring politely about something they already know, and his striding, exemplary male forms frozen in masculine intention, appear before us in an ideal noon, as if at the equator of a distant, undisfigured planet. Ponge would have approved. He noted of the figures great and small: ‘No shadow. (As in dreams.)’

In her catalogue essay Catherine Grenier guides us through Giacometti’s Surrealist period, from the end of the 1920s to the mid-1930s, when he trod a fine line between the orthodox tendency, under André Breton, and the dissident faction grouped around Georges Bataille. Several of the well-known Surrealist works, in one or another version, are on show here. One of the finest, a bronze version (1934-35) of the Invisible Object, belongs in the Surrealist canon by the skin of its teeth, having more to do with luminous transfiguration and less to do with male desire in the presence of fetishised body parts. An elongated female nude, seated with outstretched open hands, it calls us back to Giacometti’s earlier fascination with Egyptian and ‘primitive’ art, and forward to the imposing figures that take pride of place from the end of the 1940s. (It’s easy to forget what a resounding influence Surrealism exercised in postwar Europe and the Americas, long after Giacometti had grown away from it, and set his own course.) But what exactly is the invisible object – the space sculpted by two cupped hands – that the figure is holding, a little in front of her? We don’t put this question straightaway, because we’ve been distracted by the grace of her slender fingers, which the poet Yves Bonnefoy took as homage to the Virgin’s hands in Cimabue’s Maestà at the Louvre. Not long before he died Giacometti said it was his favourite piece in the museum. Bonnefoy nonetheless comes up with an answer: the invisible object, he reckons, is the work that Giacometti will go on to produce, and, in this sense, the piece is full of promise.

Breton, who set eyes on the Invisible Object before it was finished, was plunged into authoritarian dismay. He took Giacometti off to a flea market for a lengthy tête-à-tête. Giacometti came home from this ordeal with a curious metal object resembling the grille of a small petrol engine, but somehow, too, a cross between a science-fiction visor and a Venetian mask. In Breton’s mind, this strange discovery ensured the success of Giacometti’s finished piece, rescuing it from the shallows of affect (something to do with the artist’s mother, he suspected, or maybe a girlfriend) and allowing it to achieve a proper gravitas. This mysterious piece of junk was never incorporated into Giacometti’s finished figure – he didn’t do that kind of thing – but it has a tenuous resemblance to her head, and maybe that was enough to convince Breton that he’d made a timely intervention. In 1935, as Grenier explains, he was cast out by Breton for the sin of figuration (he had the gall to work with a sitter in front of him). Henceforth he could do as he pleased in his studio, shifting his gaze two or three metres from the work in progress to the model, and then back again; seeing straight and then askance; looking out and then somewhere else that we might as well call in, shuttling to and fro across a shifting threshold between two different kinds of space – the space where things appear to us in ways we can put a name to, and the wilful space in which modernism went about its mission of seeing and naming as if for the first time.

This productive back-and-forth, attended by hair-raising worries about how to situate a figure in relation to the viewer or maker, eventually gave rise to his figures’ characteristic whipped and puckered surfaces, thumbs and fingers performing revision on revision: tearings, distressings, pinchings, extrusions, deeper depressions inflicted by the perpetrator’s thumbs. In every minuscule crater and promontory of his post-Surrealist surfaces an anxious damage is visited on the material. Yesterday’s wounding is followed by this morning’s rapid, post-violence repair, and then undone as Giacometti begins a new round of injuries on the convalescent clay, or takes a knife to the plaster, not yet fully cured. All this is performed in long spells of over-attentiveness, with brief bouts of respite. Giacometti liked to stay at the workface, right up close, and lose himself in these endless interrogations, refusing to take yes for an answer. The results stand before us, in all their magnificence, if not dead to the world then close to exhaustion.

This lifelessness is not inertia. In the groups of small figures – for instance, The Square and Three Men Walking from the 1940s, or The Glade and The Forest from 1950 – a kind of flagless semaphore (look, no arms) allows each member of the tiny tribe to know its place and the others’ status. Leiris thought of them as ‘juxtaposed, rather than grouped’, but they have the quiet self-consciousness of kin gathered for a family occasion. Genet was intrigued by something even more striking when he was hanging out in Giacometti’s studio. The finished stand-alone pieces, he records, underwent a subtle change whenever the artist was at work on ‘one of their sisters’, as if they secretly welcomed the expansion of the colony. A glorious sisterhood of statuary is on display at Tate Modern; and the stand-alone figures, brought together in the same space, enjoy the complicity of the groups, quite unlike the solitude we ascribe to them. Having done time, Genet – whose portrait hangs in the eighth room of the show – was well placed to notice this: in the exercise area of a jail, inmates can communicate without the warders noticing the signals, even if they know something is up.

Genet also felt that these motionless, somewhat mortified figures often seem to be approaching us, and then receding, coming and going between ‘the furthest distance’ and ‘the closest intimacy’. Maybe this is so. It all depends on a viewer’s susceptibility. Giacometti spoke freely about his struggles with distance, and the scale of his three-dimensional works, but his thoughts aren’t always helpful. That a small figure in the real world is probably further away from me than a larger one is obvious enough, but a diminutive piece of sculpture that asks to be imagined at a distance is up against the overwhelming fact that ‘depth’ – to borrow a line from Merleau-Ponty – ‘is born before my gaze’, and continually reinscribed as I make my way through a room or a landscape. Are we meant to experience Giacometti’s larger works as if they were up at our faces?

In La Force de l’age, Beauvoir remembers Giacometti taking a shine to her protégée ‘Lise’ (actually Natalie Sorokin) when he came back to Paris after the war. Sorokin was poor and Giacometti would stand her a lunch or a dinner whenever occasion arose. Sometime in 1945 or the following year he invited her to his studio, and Beauvoir asked for a report on the pieces. Sorokin was stumped for an answer. ‘I don’t know,’ she said. ‘They’re so small.’ Beauvoir, too, was disconcerted the first time she saw them. The largest, she recalled, was ‘scarcely the size of a pea’. Daunted and isolated by the size of the room at Tate Modern, they are like emblems designed to fit in a locket but displayed in a huge chest with a gaping lid: tiny, kinless figures, which nonetheless impel us towards them, hunching in ever closer inspection, like exquisite toys. (‘Lead soldiers’ was one of Ponge’s jottings as he scanned the sculpted pieces; and then, on reflection: ‘more like lead conscientious objectors’.)

In 1954 Sartre wrote of Giacometti that his painting and sculpture were ‘inseparable and complementary’, but in an essay six years earlier, he was in no doubt that the first may have been an unreliable guide to Giacometti as he approached the second. It isn’t possible, he explained, to look at a piece of sculpture as if it existed in pictorial space, where ‘the distance from the figures to my eyes is imaginary.’ On the contrary, we can only experience statues in three-dimensional space, and we can stand as close or far as their surroundings permit, since we and they are in a world where we can enjoy ‘real relations with an illusion’.

But Sartre was satisfied that Giacometti had made our habit of wandering around a piece of classical sculpture as empowered, inquisitive spectators – coming and going, approaching and receding as we wished – a thing of the past. Giacometti’s pieces, he felt, were so immediate, so fully revealed from the moment we set eyes on them – ‘bursting into the visual field’ – that there was nothing to learn by moving closer. Unlike Genet, who sensed them coming towards him, Sartre perceived them at the same distance wherever he stood. Moving in closer, he says, ‘you will have the impression of running on the spot.’ Giacometti had achieved a ‘compression’ of space. Which I guess is to say that he was able to create the illusion of distance after all, and contrived a dramatic shift in our experience of the modelled work in three dimensions.

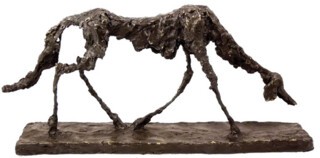

Yet crucially for Sartre this distance is invariable, it has no bearing on our restless adjustments for depth in the visual field as ‘a relation from me to things’ (Merleau-Ponty again); and it remains that way for all of Giacometti’s sculpted pieces, however large or small. Sartre called it a proper ‘human distance’, which is perhaps to say that whatever their sense of intimacy and estrangement, human beings are always the same distance apart. Sartre thought long and hard about the obstinacy of these figures, and so should we. But what to make of their post-mortem aspect, chipped from the lava of the studio in the rue Hippolyte-Maindron? The great pieces take the weight of war and mass extermination, as Sartre recognised – ‘the fleshless martyrs of Buchenwald’ – and this is one register, richly human and historicised like all evocations of the death camps, in which they seem to address us. René Char likened them to suffering rubble (‘tel des décombres ayant beaucoup souffert’) or the slender windows of a ‘burned church’. Are we meant to greet them as if they had emerged from a night of chaos and barbarism, with Giacometti’s astonishing bronze dog shambling ahead of them like a cur through the smouldering remains of a European city?

The trouble there is that The Dog (1951) is modelled with an eye for caricature and bathos, like something out of Daumier. Giacometti’s human forms can appear to us in this light too: stranded between being and nothingness, as Sartre saw it – he made heavy weather of it – yet in a deadpan, absurdist manner, like a motionless crowd of Vladimirs and Estragons. Giacometti, who modelled the plaster tree for a 1961 production of Waiting for Godot, felt in the end that it was a terrible prop, and so did Beckett. Genet, however, was a huge fan of Giacometti’s bronze dog, even though he couldn’t see where a four-legged animal fitted into the artist’s battalion of two-legged figures. Eventually Giacometti set him straight: it wasn’t an animal, or not exactly. ‘It’s me,’ he said. ‘One day I saw myself in the street like that. I was the dog.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.