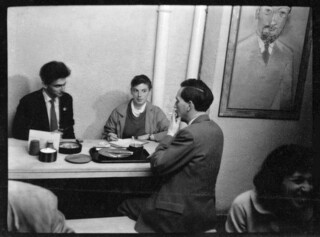

It was the mention of chili con carne, an exotic dish in the late 1950s, on a menu at the exhibition about the Partisan coffee house at Four Corners Gallery (until 27 May) that provided the appropriate madeleine. Looking at the exhibits, above all the splendidly atmospheric photographs by Roger Mayne, made me realise that the coffee house was by no means the unalloyed disaster I – as someone deeply involved in the project – have always assumed. It lasted only four years and financial disaster was narrowly averted after it closed in 1962, but like many socialist undertakings before and since it was a creative success.

As Eric Hobsbawm, originally a sharp opponent who later joined the ‘management committee’, put it with characteristic clarity, ‘whoever backed the Partisan must have known it was not a serious business proposition but something of the youth and sheer utopian confidence of Ralph’ – as Raphael Samuel called himself at Oxford – ‘must have appealed to middle-aged men whose moral universe lay in ruins around them.’ Samuel was a brilliant historian and a charismatic but deeply irresponsible man, who had dreamed up the idea but, without telling anyone, spent an excessive amount on furnishing the site – ideally situated in Carlisle Street in Soho. It was an anti-espresso bar, conceived by these personifiers of ‘proletkult’ as an antithesis to ‘alienation, commercialisation and the decline in traditional class consciousness and working-class culture’ – though few if any of the customers were other than middle-class.

The project was not helped by the ‘modernist’ decor. The architects, Hobsbawm wrote, ‘did their level best to make the stark interior resemble a station waiting room’, although its severity was relieved by paintings, drawings, etchings – and chessboards. To make matters worse the menus, also designed by Samuel, were eclectic, part East End Jewish, part Viennese and part 1950s British, an unholy and inexpertly created mess from borscht to ‘Breconshire dumpling’ – whatever that may have been. Further insuperable problems were created by bad management.

Nevertheless, the venture marked a sense of newfound moral, cultural and social freedom reminiscent of the Flore and the Deux Magots after the liberation of Paris in 1944. The speedy liberation of the Marxist – and indeed socialist – left came in 1957 after the majority of communism’s finest intellects, headed by Edward Thompson and John Saville, quit the Communist Party following the Soviet invasion of Hungary. As the exhibition’s curator, the historian Mike Berlin, explains in the catalogue, the venture ‘deserves to be celebrated. The Partisan embodied a radical tradition that had a profound influence on the political counter-cultures of the 1960s and 1970s, a break both from Stalinism and the narrow orthodoxies of the Labour Party.’

As the spiritual home of the New Left it helped to cultivate a new and distinct dissenting culture embracing everything from the Bomb to Beat poetry. Acting as ‘a space for extended debate and discussion’ from 10.30 in the morning until midnight, it hosted meetings addressed not just by usual suspects such as Michael Foot, Barbara Castle, Kenneth Tynan, the publisher John Calder, Doris Lessing, Michael Redgrave and Wolf Mankowitz, but also such distinguished figures as William Empson. ‘Events’ were held in the basement where various tendencies including ‘skiffle, trad jazz, performance art and radical politics collided, blending spontaneous giggling with poetry, banjo and washboard’. The sheer scale of the activities provided a great deal of usually favourable publicity. The Observer – and less predictably Vogue – noted the phenomenon. The BBC even sent along a crew headed by the inevitably condescending future Tory MP Chris Chataway. The whole radical phenomenon was taken seriously enough for the Met to plant informers disguised as chess players.

The atmosphere surrounding the New Left and its Soho headquarters bolstered two new publications, the New Reasoner and the Universities and Left Review, which involved not only Thompson, Saville and Samuel, but also Stuart Hall and the philosopher Charles Taylor. The two merged in 1960 to become the still thriving New Left Review, and for more than ten years after the Partisan’s closure the NLR enjoyed rent-free offices.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.