If anything justifies the use of the word ‘iconic’ to mean an instantly recognisable image with emotive associations it is representations of Churchill. The cigar, the V for Victory sign and the siren suit are the stuff of caricatures, oil portraits and monumental sculpture from Parliament Square to Fulton, Missouri. So potent was his image in the early months of the Second World War that the sculptor Eric Kennington believed it could literally be a weapon. He suggested to Kenneth Clark, who chaired the War Artists Advisory Committee, that polished brass models of Churchill, filled either with propaganda leaflets or delayed-action explosives, might be dropped over Germany. Clark pointed out that this would be very expensive, and suggested that perhaps just a few might be dropped ‘over Berlin and Josef Goebbels’. Apart from the impracticality, Clark had his doubts, as Jonathan Black notes in Winston Churchill in British Art (Bloomsbury, £25), as to whether Churchill was going to be an asset or a liability in the war effort.

It is one of the ironies in Black’s brisk and enjoyable biography through images that the massively solid figure that dominated the public imagination was built on a career in which triumph and disaster alternated with remarkable rapidity. Ernest Townsend’s painting Winston Churchill as First Lord of the Admiralty, commissioned for the National Liberal Club in 1915, underwent sympathetic sufferings with its subject on the scale of Dorian Gray’s. By the time Townsend started work Churchill had resigned as First Lord and by the time he finished Churchill was out of favour with the club for having supported Lloyd George’s bid to replace Asquith as leader. It was decided not to hold the expected presentation ceremony and the picture was hung in an inconspicuous committee room. In 1917, when Churchill became minister of munitions, an official unveiling was mooted and the club considered moving the picture to the dining room, but by 1921 he was out of favour again and the portrait was taken down and stored in ‘a dry well-ventilated place’, which Black suggests was a euphemism for the cellar. It went up again to the smoking room in 1923 and back to the basement the following year when Churchill rejoined the Conservative Party. In 1940, when he became prime minister in the wartime coalition, it was dusted down and enshrined on the main staircase, where it still hangs. It was formally unveiled in 1943 in the presence of Churchill who, at 68 with a receding hairline and advancing stomach, no longer much resembled it.

Churchill’s long career makes a history of his portraits a history of British art from Sickert to Gerald Scarfe. This is the premise of Black’s book, which ranges over cartoons and photographs as far as Clarice Cliff’s Art Deco Toby jug of 1938-39. Made during Churchill’s second stint as First Lord of the Admiralty, it depicts him sitting on a bulldog and holding a battleship over the inscription, ‘May God defend the Right.’ One point on which most of these very diverse artists agreed was that the raw material was unpromising. The New Zealander David Low, who became Churchill’s favourite cartoonist, first met him in 1922 and sized him up with a professional eye: ‘He belongs to that sandy type which cannot be rendered properly in black lines. His eyes, blue, bulbous, and heavy-lidded, would be impossible. The best one could do with him was an approximation.’ Low resolved the floating composition into round bulging eyes and the rippling extra chins about which Churchill was sensitive. Portraitists had a harder time of it. Churchill’s features were in constant motion, reflecting a temperament William Orpen described as ‘wax and quicksilver’. Sickert’s oil painting of 1927 best catches that plasticity in an image that recalls the similarly sandy and baby-faced Dylan Thomas.

Churchill’s longest-lasting, albeit stormy, artistic relationship was with his cousin, the sculptor Clare Sheridan, who first made a head of him in 1919. Even for her he wouldn’t sit still for more than a few minutes. On that occasion he ‘looked stubbornly out of the window at a cedar tree which had taken his fancy and which he was determined to capture in paint’. Sheridan, an equally mercurial character in her way, soon afterwards began an affair with the head of the Soviet trade delegation in London. While Churchill was waiting for her to join him on a holiday cruise she went to Moscow where both Lenin and Trotsky obligingly posed for hours while asking penetrating questions about her cousin Winston, his opinions and the strength of support for his opposition to Bolshevism. Churchill was so furious that he declined to buy the head she had made of him, but later forgave her and sat, or fidgeted, for her several times.

If Winston was the icon, his wife Clementine was the iconoclast. In January 1978, a month after her death, their daughter Mary Soames wrote to Graham Sutherland to confirm what had been long suspected: that her mother had had Sutherland’s portrait of Churchill destroyed. Commissioned by the joint Houses of Parliament to mark his eightieth birthday, it had been intended to hang in the Palace of Westminster after his death. Sutherland by then felt that the row that had surrounded the picture was ‘past history’, but its destruction was, he said, ‘an act of vandalism’ on a scale rare outside wartime. Lady Churchill had form. She had put her foot through a preparatory sketch by Sickert. When the sculptor David McFall, whose bust was the last image of Churchill taken from life, met her, she told him what she had done to the Sutherland, adding ominously, ‘accidents can happen to sculpture as well.’ He duly altered the mouth in accordance with her wishes, to remove the evidence of a stroke. Ivor Roberts-Jones thought she would have ‘turned artillery if she could’ on his statue for Parliament Square, now perhaps the most familiar single image of Churchill.

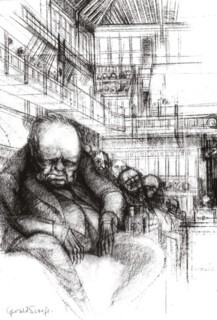

Roberts-Jones’s figure and Oscar Nemon’s posthumous full-length statue, which stands in the Commons’ lobby, its left foot shiny where MPs touch it for luck, mark a high point for Churchill’s image and for figurative sculpture. The banality of Anthony Dufort’s Margaret Thatcher of 2007, which stands opposite Churchill in the lobby and which MPs are not allowed to touch in case they damage it, demonstrates the sharp decline. Attitudes to Churchill have also shifted. The hostility of the 1960s is palpable in Gerald Scarfe’s Sir Winston Churchill on His Last Day in the House of Commons, 27 July 1964, which shows him ape-like and shrunken, with distended stomach and skeletal hands. This century has generally been kinder, even teasing. In May 2000 a guerrilla gardener who was taking part in an anti-capitalist demonstration in Parliament Square put a strip of cut turf on Churchill’s head to give him a mohican. It was a witty gesture, more ironic perhaps than its author realised, for on his American side Churchill was rumoured to be part Cherokee. The image gave Banksy the idea for his breakthrough exhibition Turf War, which ran for only three days in July 2003 due to unspecified ‘legal problems’. The satire was not aimed at Churchill who, Banksy pointed out, had fought in the First World War and been impressively drunk ‘most of the time’ when leading the country during the Second. The image was there to shame the focus-grouped and Photoshopped Blair regime which had gone to an ignoble war in Iraq four months earlier.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.