Paul Nash is as close as we come, many think, to having a strong painter of the English landscape in the 20th century. The uncertainties built into the wording here are part of the point: Nash spent his working life trying to decide if ‘the English landscape’ was something that had an existence, as a value for art, beyond, say, 1918; and what the difference was, in landscape painting, between strength and histrionics; and whether remaining ‘a painter of the English landscape’, with all that followed in terms of a settling of accounts with Constable and Turner, and Blake and Palmer, and Crome and the watercolourists and Ford Madox Brown, was at all compatible with being a painter ‘in the 20th century’. The pressure of this last question – or indeed of all three – is not to be collapsed into shorthand of the kind: ‘Wasn’t English landscape bound to be an exercise in nostalgia?’ or even: ‘How could a non-duplicitous celebration of the countryside possibly survive in a culture whose active, evolving identity depended on facts of industry and urbanisation – the red-brick terrace and the four-square mill, the ribbon road lined with Stockbroker Tudor, the public footpath avoiding the factory farm, the commuter village with jumps in the fields, Rain, Steam and Occasional Work Stoppages?’

It could have survived perfectly well. Perhaps it did, in John Nash’s (Paul’s younger brother) re-doings of Constable country, or Stanley Spencer’s topographies of Cookham. Landscape painting had always been, essentially and productively, nostalgic: the cult of ruins had mutated, on the whole without pain, into a celebration of French peasant smallholding or the view from the Glacier Hotel. Effectiveness, in a work of art, is never to be measured in terms of honesty or accuracy or up-to-dateness – only by the power of the preserved fiction to put up-to-dateness back into the bruising flow of time.

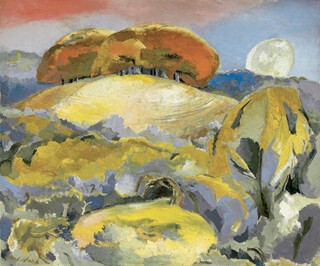

Nash’s anxiety – and the impression grew on me, the longer I spent at Tate Britain’s retrospective (until 5 March), that his painting was shadowed by constant worry, as if he could never be sure whether his latest reworking of Swanage-plus-Avebury looked too well behaved or too over the top – was not general or ‘cultural’. It didn’t derive from some half-admitted, half-repressed bad conscience about landscape being un-‘modern’. Nash’s was a naturally decisive cast of mind. Along with many of the painters who matter most in the 20th century, he was entirely capable of saying ‘to hell with modernity’ when it suited him, and capable also, when modernity came to him in its true hellishness, of putting all his gifts at its service. Totes Meer – the glamorous surf of smashed Luftwaffe plane parts that he painted in 1940-41 – does seem to me, for reasons I will set out later, his best work. And however dependent his Menin Road of 1919 had been on over-obvious ‘Cubist’ geometry, it remains – at ten feet wide and six feet tall – an astonishing response to the new look of war, especially if one remembers that the artist, then aged 29, had taught himself oil painting only a year or so previously. The scatter of tinsel pinks and oranges in the Menin Road foreground has latent within it the triumphs of colour he managed a quarter-century later, in Landscape of the Moon’s Last Phase and Landscape of the Vernal Equinox. Palmer walks the earth again in them, plangent and fiery and full of a dying man’s rage.

It is the conjunction of Palmer and Cubism in the preceding sentences, or of twilight glamour and ‘modern’ geometry, that points to Nash’s problem. His dilemma was technical. He rightly saw – he discovered in practice – that his art would amount to precious little if he couldn’t find ways to keep the specifically English forms of landscape mooning alive in his colour and space. One thing the Tate retrospective brought home to me was the depth of Nash’s attachment as a young man to Blake, and to the Rossetti strain of Pre-Raphaelitism; and this helped me understand why so much from the past of the landscape tradition that might have helped him – been adaptable to 20th-century purposes – remained essentially unavailable to him, wide as his later horizons became. Constable’s feeling for the particular kinds of division and confinement associated with English agriculture never appears to have touched him deeply: he was sympathetic to his brother’s endless circling round the sun of Stoke-by-Nayland, but one looks in vain in his own painting for field systems or farm machinery or scenes on a navigable river. They were stops on the way to the Downs. Palmer’s high-Tory pastoralism seems to have embarrassed Nash: he ignored the village and stared at the rising moon. This meant that the strain of hedge-by-hedge empiricism in the 19th-century landscape tradition – I associate it with Madox Brown’s great English Autumn Afternoon, but it had a robust ‘naturalist’ afterlife – was essentially a closed book. And this cut Nash off from the modifications of naturalism that might have served him best: the wave after wave of French invention that led from Millet and Courbet to Seurat and Cézanne. Why was it that English Impressionism (wretched appellation, but let’s retain it for convenience) was so profoundly feeble, in comparison with the Australian or North American or Dutch? I have no answer, but I know that Nash paid a high price for Impressionism’s being lost in translation. It was the reason, I think, why Turner’s version of opticality remained inaccessible to him till almost the end. It was the reason Nash could never look properly at Cézanne: never move beyond an understandable impatience with the Bloomsbury cult of ‘construction’ and settle accounts with Cézanne’s indispensable colour.

I came away from the Tate retrospective, as I often do from shows of English 20th-century art, thinking it sad that for so long – for most of the period between the wars – Nash’s gifts as a colourist were kept in a chokehold. I think I see why. The gifts, when the artist gave into them, were essentially for showmanship, for garish, acidic, factitious effects: impossible pinks, sinister yellows, Blake-type battles of sun and moon, the edges of everything sizzling with phosphorescence. But this wasn’t serious – that was its glory, when it came. It was a rush of vulgar desperation, with something of Bonnard’s or Nolde’s turning their backs on reality.

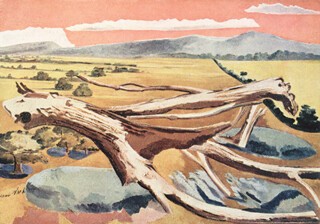

Of course I recognise that a life’s work in painting cannot proceed at fever pitch. Nash’s late pictures are dances of death. But Nash in the 1920s and 1930s, before illness exacerbated and clarified things, seems to me already constantly looking for a way to escape as an artist: to release his strange gifts, to indulge in wild chroma, to thin objects down to tissues of light, to have painting be theatre. There is a series of studies in the Tate show, watercolours and photographs, which end in an oil painting called Monster Field (1939). It is a pity that the painting itself, which hangs in Durban, did not make the trip. (A later elaboration called Monster Shore is in the exhibition, but the original idea strikes me as having been stifled in it – lost in a Dali-plus-Ernst assemblage.) Writing a year later in the Architectural Review, Nash said that what had triggered the painting in the first place was a shattered elm in a field by the Severn, which had struck him as looking like the horse in Blake’s Pity (he slightly misquotes the lines Blake was drawing on from Macbeth – ‘sightless couriers of the air’ become ‘sightless cousins’ – which is always a good sign; and the resemblance between tree and horse gets quickly forgotten):

The declining sun suffused the evening sky to a brickish red; beneath which the Malverns piled up intensely blue. A cornelian glow illumined the heavy summer green. The strange creature at hand seemed more ghastly, stained by this sweet tint. Something about its headlong purpose recalled Picasso. It was eminently bovine and yet scarcely male. Surely this must be the cow of Guernica’s bull. It seemed as mystical and as dire.

Charles Harrison, who quotes these lines in his excellent English Art and Modernism, immediately cautions us against reading Nash’s painting in the light of his prose. ‘As a writer,’ Harrison says, ‘Nash was given to whimsy and to an exaggerated fancifulness not always redeemed by irony … In the best of his paintings, on the other hand, his technical interests and competence served to discipline his fancies.’ I’d agree with that wholeheartedly (minus the ‘best’), but with the strong final rider: ‘Alas.’ The Durban version of Monster Field does look, on the basis of reproductions I could track down, to have risen in the end to a fine technicolour tawdriness: it is hectic and sweet and ghastly and fanciful, in the way of Picasso round 1930. But there are, for my taste, too few Nash paintings like it during the interwar years, and far too many Woods on the Downs and Equivalents for the Megaliths.

It is miserable to dwell on a very good painter’s limitations, and I shall be brief. Woods on the Downs is a much admired and reproduced picture – it is understandably the cover image for Harrison’s book – and I wish I could admire it too. But it seems to me handcuffed by the ‘Cézannisme’ Nash rightly tried hard to resist. The drabness of its colour is unnecessary – it stands for ‘construction’, nothing much else. (Put the Nash alongside a Derain from 1912, let alone a Picasso from 1908, and the point is clear.) The cleverness of Nash’s pictorial arrangement – his ‘bold’ basic asymmetry, his discreet faceting, the dreadful rhyming and dovetailing of his scene’s paths and branches – connects with nothing vital in the motif. Put the darn trees up on the hill, say I. Let them lord it unashamedly, melodramatically, as they do in The Moon’s Last Phase. Flood the foreground with English gloom, if that’s what you’re trying for. Cancel the ambiguous half-shadows. Get ‘Cubism’ out of your system. Borrow a line from At Castle Boterel: ‘As the drizzle bedrenches the waggonette …’

I have no doubt that Nash’s engagement with Surrealism was driven by the kinds of doubt about his own painting I have just voiced. But I don’t think the engagement did the painting a lot of good. Surrealism, if an artist has to be influenced by it, is best taken in operatic overdoses for a very short time (in the way of Pollock or Frida Kahlo). Well-tempered Surrealism is a contradiction in terms. Landscape and Surrealism are anyway uneasy bedfellows: ‘dreamscapes’ (that Hollywood coinage) are entirely the invention of the wide-awake. The megalithic clutter on Nash’s Jurassic coast is never vulgar enough. You want him to get to the beach and wallow in Thalassa. There are one or two photos he took of Avebury that seem to me to capture the place’s unlikeness: in one a great stump of stone is parked next to Nash’s Austin 7. I wish the car had got into his paintings occasionally, and the stones all the time had looked less like big Henry Moores. I wish Nash had learned more from his friend Edward Burra.

And so to the dump at Cowley. Totes Meer is quite a large painting – five feet wide and going on for three feet tall – and it puts its new size to good use. Gone is the Chirico staffage, and in its place are endlessness and invariance – the qualities in nature that Nash had always seemed to respond to most deeply.

Paint me a cavernous waste shore

Cast in the unstilled Cyclades,

Paint me the bold anfractuous rocks

Faced by the snarled and yelping seas.

Snarling and yelping in Totes Meer are subdued to a surfside grumble: the sea of machine parts shimmers in the moonlight. It hardly seems to matter that the flotsam is military: what moves the painting into new territory for Nash is the balance struck within the rectangle between incident and repetitiveness, or emptiness and detail: wave after wave of broken wings and fuselage – they could as well be tractor bodies left over from a botched Five-Year Plan – rolling monotonously across the dune-scape. (Cowley collides with Chesil Beach.) Colour is active in every square inch of the canvas. Gun-metal greys are played off against cartoon greens, blues, pinks, wintry dead browns; the dune yellow is savage, with a horror-movie shadow louring at its edge and great gashes of red traced across it. Even Nash’s signature is written in Soutine blood. The moon and its halo are schmaltz.

Totes Meer is a beautiful painting, and the fact that the word applies so easily – that Nash is not in the least apologetic about his aestheticising of death and machinery – is the sign of an artist at last sure of his ground. Modernity had presented itself to him again, as it had on the hill at Passchendaele: it seems that the 20th century only came to Nash, as something paintable, in the form of total war. This has its own bitter truth to it; but part of me regrets, I admit, that Nash never encountered another, more ordinary form of modernity – the edge of the city, the clank of the combine, the exhausts of suburbia – that he felt he could put in a picture. I think of Pissarro in South London in 1871, fitting Dulwich College and the Crystal Palace and the rows of decent semis into his pastoral. But I know that this reference moves me too close to the ‘nostalgia’ police.

The terms I proposed at the start of my review were deliberately limited. Deciding who might be the best candidate for ‘strong painter of the English landscape in the 20th century’, and what strength in such a case might involve, has its interest, but may in the end not be the main thing. In a century of migrations and dépaysements, mapping motif onto birthplace is most often deceptive. Arthur Lismer and Fred Varley were born in Sheffield, and certainly ended up infinitely better landscape painters than … well, I’ll not name names. But the land that mattered to both of them was Northern Ontario. The great Tom Roberts was born and raised in Dorchester. Charles Conder was the son of a London railway engineer. These facts are no doubt relevant to their love of the light and space of Australia, but can hardly be thought to qualify it. The ‘strongest 20th-century landscapes by an Englishman’, to change the form of words slightly, seem to me pictures of Jerusalem, Toledo and Andalusia by David Bomberg. (It is no doubt hard to look past subsequent history and accept Bomberg’s Zionism for the strange thing it was, but paintings like his Pool of Hezekiah and Rooftops, Jerusalem are as close to Corot in Italy or Seurat at Gravelines as anyone since has come.) Frank Auerbach’s versions of Primrose Hill are unique testaments to the advantages of internal exile. The list could be extended – Hockney’s Los Angeles comes to mind. Paul Nash’s England may be touching, that is, and finally dazzling – like the last seconds of a firework display – but the landscape that ‘Englishmen’ cared for as England came to an end turns out to have far-flung boundaries.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.