In the Beat constellation, Allen Ginsberg’s star now shines more brightly than the rest. True, Jack Kerouac and William Burroughs glowed on in the aftermath of On the Road (1957) and Naked Lunch (1959); Brion Gysin, inventor of the cut-up technique, is still visible on a clear night. But the beautiful Lucien Carr, an Alain Delon lookalike drawn into the Beat circle by a smitten scoutmaster who stalked him across America until Carr pulled out a knife and killed him in New York, no longer emits much light. Nor does poor Herbert Huncke, ‘sad, sweet, dark, holy’, as Kerouac describes him in Desolation Angels. Parts of his notebooks were published in the 1960s, but he only really sputtered to life again in 1990 with an autobiography, and died a few years later.

These names belong to the original small group of friends who met in New York in the early 1940s. Within ten years Ginsberg had moved to San Francisco and Beat was a media legend. Lawrence Ferlinghetti, co-founder of City Lights bookstore, and publisher of City Lights editions, gave him a warm welcome; Kenneth Rexroth, older by twenty years than Ginsberg and the New York crew, was briefly a mentor. The poet Gregory Corso came out west and joined Ginsberg. Neal Cassady, the movement’s mascot/muse, whom Ginsberg and Kerouac had met in the 1940s in New York – Kerouac cast him as Dean Moriarty in On the Road, Ginsberg had sex with him – was already living outside San Francisco with his wife, Carolyn Robinson.

In 1955 Rexroth presided over a famous poetry reading at the Six Gallery in San Francisco. Ginsberg read the first section of Howl; two younger poets, Michael McClure (early twenties) and Gary Snyder (mid-twenties), read on the same night. So did Lew Welch, who disappeared years later in the Sierra Nevada. Barry Miles, who has written the introductory essay in the catalogue for the Centre Pompidou’s exhibition Beat Generation (until 3 October), identifies the reading as the movement’s ‘birth certificate’: the following day Ferlinghetti cabled Ginsberg with an offer to publish Howl in his Pocket Poets series.

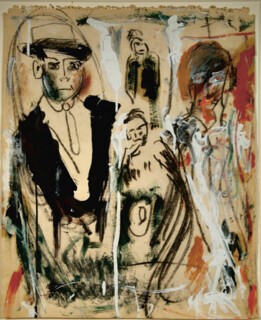

Two nagging problems about a Beat retrospective. Who did you forget to include? (I’ve just struck the poets Philip Whalen and Philip Lamantia off the record of the Six Gallery event.) And when do you reckon it grinds to a halt, or something supersedes it? Anxiety is a reliable guide here, and Philippe-Alain Michaud has covered as many bases as a curator can hope to do. His show at Beaubourg is planned in the manner of a defensive shield: incoming criticisms probing for gaps will simply bounce off, detonating in the ether once they encounter his dome of contingencies and associations, fashioned from a wealth of manuscripts, published texts, paintings, drawings, photos, sound recordings, experimental films, home movies, typewriters, phonographic players, tape recorders, even a Burroughs adding machine, invented by the big man’s grandfather. Near the entrance we’re greeted by a looping, annotated diagram of Beat affiliations, about four metres long and a metre high – a psychohistory of the movement, recording who met whom and where, and mapping the passage of dozens of people from the early 1940s to the end of the 1960s. No one seems to be missing. And there’s no shortage of ambient sound. Songs collected by Harry Smith for the Anthology of American Folk Music (1952) drift on the air in the first rooms; in the last, we can hear Paul Bowles’s recordings (1959-61) of traditional Moroccan musicians.

Beaubourg’s trophy exhibit is Kerouac’s highway-scroll manuscript of On the Road, composed in 1951: at more than thirty metres, it runs most of the length of the second room, inviting visitors on a pilgrims’ route to the true north of the Beat kingdom. All the same, it’s not the heart of the show. Michaud has collected as much material as he can from New York, San Francisco, Tangier, Mexico, even India, where Ginsberg spent most of 1962, and Japan, where he visited Snyder and his partner, the poet Joanne Kyger, in 1963. But Paris is Michaud’s real centre, in particular the Beat Hotel, a cheap rooming house in rue Gît-le-Coeur, where Beat as a form of hysterical alchemy came to a head at the end of the 1950s.

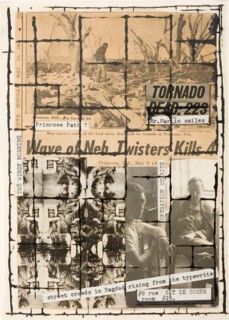

The great feats in those years are Burroughs’s completion of Naked Lunch, Gysin’s ‘discovery’ of cut-up, after slicing through a wad of newspaper as he was making a passe-partout, and the beginnings of Kaddish, Ginsberg’s extraordinary poem to his mother, Naomi. Michaud doesn’t try to present Paris as the Beat city par excellence, but Ginsberg wrote several good poems besides the first part of Kaddish while he was lounging ‘on a bed in Paris/sunglow through the high/window on plaster walls … alone in old red under/wear’ (from ‘Europe! Europe!’, 1958). The Olympia Press, run by Maurice Girodias, was a ten-minute walk from the hotel, and an obvious destination for Naked Lunch. Girodias had already published The Thief’s Journal, Lolita, various unreadable works by Henry Miller, pornographic novels by Christopher Logue and Alexander Trocchi, a para-Beat from Glasgow, and Trocchi’s ghosted volume of the Frank Harris memoirs (Trocchi was Olympia’s ‘top all-out literary stallion’, according to Girodias). Olympia went on to publish two more works by Burroughs, The Soft Machine and The Ticket That Exploded.

Paris was also a rendez-vous with European modernist traditions for Ginsberg, Burroughs and Corso. Erudite and alert, Ginsberg led the others in this ring-a-roses with the grandees. They met Duchamp, Man Ray and Benjamin Péret at a party (fifty years before the selfie, Ginsberg snogged Duchamp). They ran into Tristan Tzara. Ginsberg and Burroughs paid a visit to Céline in the suburbs. They were greeted by his ferocious dogs (Burroughs must have liked that). Céline explained that he took them with him when he went out, to keep ‘the Jews’ in the neighbourhood at bay: perhaps it was a way of putting Ginsberg back where he belonged, in outer darkness.

Only he didn’t. There would have been no Beat phenomenon without Ginsberg, logorrhoeic poet and protester; illustrious, predatory queer; inventor and supporter of colleagues and hangers-on; impresario and self-appointed hero of a tradition that he put together from all kinds of sources – Buddhist, Hebraic, European, pre-Columbian – in order to loosen the American grain and leave a lasting trace. In fact American poetry was already a rich, eclectic mix when he began writing, and many non-Beat poetic paths in America would have been trodden with or without this unholy fool from Paterson, NJ, who thought he could change the course of literature by chanting a mantra, or turning Robert Lowell on to hallucinogens. (On the way to the Lowell/Hardwick apartment on Riverside Drive in 1961, with Timothy Leary in tow, Ginsberg’s partner Peter Orlovsky asked an entirely reasonable question: ‘Why are we giving psilocybin to Lowell?’ Ginsberg, according to his biographer, Miles, was in no doubt: ‘We hope to loosen him up, make him happier … We’re not dealing here with a Dionysian fun-lover. He’s a good guy with a psycho streak. We should be cautious about the dose.’ They were, and Lowell took the drug in his stride.) Even the Black Mountain poets, well established by the time Ginsberg published Howl, and the San Francisco poets, who were unsure what to make of him when he showed up in California – Jack Spicer, co-founder of the Six Gallery, couldn’t be doing with him – took him seriously. He had all-consuming ambition, and a promiscuous sense of the poetic canon, which included much of the new American work on offer.

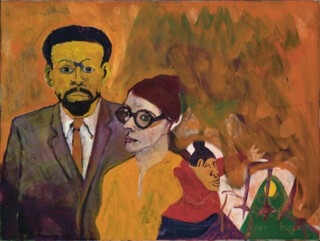

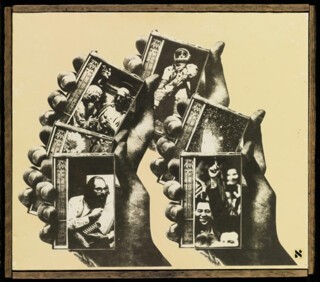

He also took a lot of photos of friends and colleagues. The show has thirty or so, mostly captioned by him in longhand in the 1980s. They hold their own with more famous photos, taken on and around the Beat scene by Harold Chapman, Fred McDarrah and John Cohen. The photographer Robert Frank is in another league; a dozen prints from The Americans, first published in Paris in 1958 with texts by Beauvoir, Steinbeck, Faulkner and others, hang alongside the Kerouac ms. Frank’s forgettable movie Pull My Daisy (1959) is on a loop in another room, and reminds us how bleakly homosocial the Beat thing could be, even when it wasn’t priapic-gay. Most of the tangential figures in this show, like its heroes, are male and white. The painter Bob Thompson and the poet LeRoi Jones (later Amiri Baraka) are rare African-American presences. The catalogue contains a fascinating interview with Joanne Kyger by Miles, and there’s a set of haiku by Diane di Prima on display, but that’s the extent of it for women. Women, Burroughs once explained to Ginsberg, only partly in jest, are bad news: ‘Steer clear of ’em. They got poison juices dripping all over them.’

The last date on the Beat-links mural at the start of the show is 1967. The scandalous fame of Beat was by now decaying into run-of-the-mill notoriety. But Burroughs and Gysin, an eccentric from the Home Counties, had earned their spurs as formal innovators, the first of the last of a literary avant-garde, while Ginsberg’s libertarian urges fed naturally into the hippie movement, and his politics led fluently from a horror of nuclear weapons to staunch opposition to the Vietnam War and the American imperium. (He’d badly wanted to love Cuba and Czechoslovakia, but was thrown out of both on visits during the 1960s).

His standing as a poet was assured in 1965 by an invitation to the Berkeley Poetry Conference, a two-week event attended by a small, distinguished group, including Spicer, Snyder, Kyger, Robin Blaser, Robert Duncan, Charles Olson, Robert Creeley, John Wieners, Ed Dorn, among others – as a colleague rather than a Beat figurehead. He was given a Guggenheim grant the same year and bought a VW camper van. His idea, I guess, was that he and his lover Peter Orlovsky would achieve tantric sublimation as they trundled round America from sea to shining sea, and on from there to the rest of the universe, with Ginsberg drawing poetic inspiration through every orifice, including Orlovsky’s. Beat had a knack of finding wild ways to be on the road without actually committing a traffic violation.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.