The exhibition Conceptual Art in Britain, 1964-79 (until 29 August), concise, intelligently installed, with something of the clarity and balance of a well-designed book, is an important occasion. And its readerly qualities are all to the good, given that the conceptualist generation (the majority were born in the 1930s and 1940s) shared a preference for working with words, if in an aggressively non-literary way. These were artists more at home at a desk than an easel, more likely to wield a camera than a paintbrush. Most preferred data to drawing, were engrossed in print culture, and avidly produced and consumed all sorts of texts. Yet their readerly and writerly habits alone do not account for work whose default tone was mostly declarative and often aggressively abstruse. Statements, definitions, grammars, propositions, indexes, tables: such bloodlessly ‘neutral’ formats were their meat and drink.

The result is an art that is not for everyone, but then few modes of art can lay claim to universal appeal. No doubt we are right to be wary of any school or style that aims to speak to all. Conceptual art does the opposite, and savours the opaque result. And for that subset of viewers interested in avant-gardism, aesthetic criteria and the destabilisation of art’s commodity status, the exhibition is essential. Many have already found their way to the show. All that is asked of the viewer, whether novice or expert, is a) to give the show enough time; b) to read both the works and the labels; c) to inspect the cases carefully – conceptual art wasn’t made just to hang on the wall; and d) to remember that though conceptualists revelled in lists, schemes, systems and graphs, a work’s format was never an end in itself.

From the beginning, precisely just what kind of art conceptualism was – and what sort of artist produced it – was considerably less clear-cut (less black and white) than the graphics it used. Perhaps the most instructive attempt to set out shared principles was drawn up in 1969 by the American artist Sol LeWitt. As befits the idiom current at that moment, the artist’s chosen format was a list of 35 ‘Sentences on Conceptual Art’, ending with the proviso: ‘These sentences comment on art, but are not art.’ Well, what is? LeWitt set down his Sentences to offer some help. Here is how they begin:

1. Conceptual artists are mystics rather than rationalists. They leap to conclusions logic cannot reach.

2. Rational judgments repeat rational judgments.

3. Irrational judgments lead to new experience.

4. Formal art is essentially rational.

5. Irrational thoughts should be followed absolutely and logically.

Printed art travels fast. LeWitt’s Sentences seem to have been written in 1968, and became available early the following year, when they were published in the inaugural issue of Art-Language: The Journal of Conceptual Art. Produced by the Art & Language Press, this was the house organ of a groupuscule called Art & Language. Founded in the late 1960s, this shape-shifting set of artists soon became known not only for its scathing intransigence in the face of the art world’s pretensions but also for pretensions of its own. Art & Language was composed of dyed in the wool contrarians. No wonder they were drawn to LeWitt’s ‘absolute’ and ‘logical’ celebration of irrational thought.

There are 26 works by members of Art & Language in the Tate exhibition and the best of them – the collaborative Map to Not Indicate (1967) by Terry Atkinson and Michael Baldwin, for example, or Baldwin’s Drawing (Typed Mirror), 1966-67 – demonstrate how conceptual art can be both bookish and mystical in ways that clarify some of the implications of LeWitt’s chosen term. Take Baldwin’s Typed Mirror: the artist began with a passage from a brief text – apparently he wrote it himself – that brings together art-world terminology (‘avant garde’ and ‘academy’), philosophical touchstones (Wittgenstein and the Tractatus), and artists who were fashionable at the time (Frank Stella, Donald Judd). Or so the published transcription tells us. As typed by Baldwin on a shiny surface called Mirralon (a mysterious medium that looks like silvery plastic foil, but is apparently unknown to Google), communicative coherence breaks down. Typed text becomes carved relief, with each keystroke simultaneously fixing and cancelling the message it engraves. Who would imagine that as an artist types up a few thoughts on the art world, the irrational, that unmooring avatar of the mystical, could flicker into view?

One possible path through the Tate exhibition involves tuning in to other moments of communicative breakdown: moments which, at their best, guide us to a clearer understanding of how this art works its spell. It is not so much that the show aims to draw us into an impromptu game of ‘spot the mystical.’ Instead it fosters our alertness to moments when form and content seem to clash, then implode. Perhaps such breakdown is inevitable when artists share their audience’s concern with, and resistance to, the forms of knowledge, distinction, difference, power and communication that shape their world. How, if at all, can art remake the ruling order? Can that order be forced to appear? What sorts of freedom do humans possess? Do we mean what we say? Can art trump speech? Can it change or erase what people perceive? How else might it reshape, even interrupt the given patterns of life?

Woven into this list of questions are echoes of the conundrums that famously preoccupied the speculations of the late Keith Arnatt. ‘Is it possible for me to do nothing as my contribution to the exhibition?’ Answer: yes and no. If one ‘eats one’s words’ (11 of them, each printed on a separate piece of paper) for the benefit of the camera, will the result suffice as ‘retractive’ art? To use photography to ask such questions inevitably results in apparent authenticity, even while the investigative, even forensic associations that cling to these images carry with them an odour of distress. In fact Arnatt doesn’t actually eat anything for the camera. A piece of pure theatre, the black-clad artist looks more than a little put off by the pieces of paper that, one by one, he holds to his mouth, but patently fails to ingest. Still, his question remains: to what world can an artist’s words and works be said to correspond? Where and how do they make a mark or leave a trace?

Inevitably visitors to the exhibition will be drawn to some means of answering this question more than others. It offers a rich array of choice, including such poetic and elusive pieces as Richard Long’s A Line Made by Walking (1967); Victor Burgin’s subtly sensory All Criteria, first published in 1970 in a Camden Art Centre exhibition catalogue for a show called Idea Structures; and Stephen Willats’s astonishingly dynamic graphite anti-grid entitled Homeostat Drawing No. 1 (1969). Drawn freehand as a field of squares linked by directional arrows, it was conceived as something like an ideal social model; the idea, as Willats later put it, rather opaquely, was ‘to produce an image that could form the basis of [a] re-modelling of that same reality’. Yet there is nothing opaque about the drawing itself, in its conception of an open, breathing model of a social whole.

Perhaps it was inevitable that visiting the Tate exhibition in June 2016, a month with more than its fair share of social and political anxieties, meant seeing the wider concerns of conceptualism more clearly than ever before. Yet the fact that the curators of the show made sure they were visible wasn’t simply an accident of fate. On the contrary, the show’s final gallery is entitled ‘Action Practice’ – presumably a purpose-built term. I reckon that its guiding concept is not simply that artistic action, or activism, meets social practice, but rather that the documentary format key to conceptualism can be used to put art into ‘active’ contact with the world. Yet although the show seems to argue that this is essentially what happened, it doesn’t explain how and why the transformation came about. The show gives its endpoint as 1979, the year Thatcher became prime minister: are we not entitled to ask what ‘action’, let alone activism, has to do with the present artistic climate?

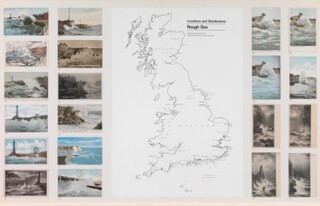

If the Tate show doesn’t answer this question, it does demonstrate that a socially conscious conceptualism was a 1970s phenomenon that includes some of the strongest works of its day. Among them are Susan Hiller’s Dedicated to the Unknown Artists (1972-76) and Mary Kelly’s Post Partum Document (1975). The first collects a total of 305 old-time postcards, many gloriously hand-tinted, all showing outsized waves breaking wildly against sea walls all over Britain – schematic maps show us where. The second, Kelly’s Document, presents one section from a diaristic six-year work dedicated to the artist’s interactions with her son from birth until he started school. For ‘interaction’, read ‘data collection’: feeds timed and noted, nappy stains described, scribbles collected, words transcribed, with all these quasi-scientific activities constituting an effort to give a partial account of the changing relationship of mother and child. Meanwhile the constant for Hiller is a typology she may well have been the first to reveal: who would have guessed that there was a time when all over Britain, photographers were poised to capture the explosive breaking of a wave?

The actions behind the work of Kelly and Hiller seem private, even domestic. Yet their presentation as art means that they are not private at all. For example, Burgin’s Possession, a photo-lithograph poster from 1976, joined image (an embracing couple) and text (‘What does possession mean to you?’), so as to confront their staged erotics with the baldest facts: ‘7 per cent of our population own 84 per cent of our wealth.’ Look back and weep for the good old days, then wonder how the population of Newcastle upon Tyne reacted when five hundred copies were fly-posted around the city centre. Did they register that as Burgin put it, the work ‘raises all sorts of questions about property relationships, sexual relationships that become property relationships, and so on’? We shall never know.

To try to say what we do know about conceptualism as ‘active practice’, look, for one last example (a key demonstration of the growing range of conceptual art in Britain), at the work with which the exhibition closes. By Stephen Willats, its title sets the tone. Living with Practical Realities (1978) consists of three poster-sized panels, each bearing the same carefully patterned configuration of words and images that document the life of one elderly Londoner, Mrs Moran. In 1975, she moved from Central London to a tower block in Hayes, and it was there that Willats met and photographed her. He also took note of the limits of her pension, her sense of isolation, the slow march of her days, the absences of human companionship. Willats learned all this, and then fitted it into the rigid diagrammatics of a quasi-sociological format – text panels, veering diagonals and all. Why? Because Willats knows full well that in deploying this cruelly rational apparatus, what is irrational about Mrs Moran’s unbearable isolation will be laid bare.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.