The golf course was on fire, but no one knew how long it had been burning. The first sign that something wasn’t right was when a groundskeeper on the course, which is a few miles west of Newcastle, noticed that the soles of his boots were heating up. The surface of the ground was hot. That was in November 2014. At that point there wasn’t much to see – until it rained and steam rose from the edge of the fourth fairway, next to the riverbank. By the end of the year, the fire was visible: smoke plumed from cracks in the earth and tree roots began to catch alight. And when the smoke blew across the fairways towards the terraced houses of Clara Vale, the neighbouring village, it bore the unmistakeable smell of burning coal.

The smouldering ground, part of Ryton Golf Club, occupies a stretch of land along the south bank of the River Tyne. It seems that the fire was fuelled by buried coal discarded by the old mine at Clara Vale and folded back into the earth. The mine, which opened in 1893, was closed in 1966 and the site later became a nature reserve. When I visited the village in late June last year, I saw few signs of the commemoration of colliery life that I had noticed in other towns in the region: no wrought iron pit wheel or squat coal truck sat on the village green as a reminder of its industrial past. Instead, Clara Vale’s stone-built terraces sat among fertile gardens, well-swept lanes and neatly tended grass verges. The war memorial at the entrance to the village was planted with wildflowers. Most of the posters pinned to the noticeboard outside the community centre were about gardening.

When the smoke from the golf course blew into Clara Vale it was an unwelcome and bituminous blast from the village’s past. Residents kept their windows closed. The washing they hung out to dry came back smelling of coal smoke. And they worried about the effects the fumes might have on their health. The golf club called in the fire service, which took a look and decided that there wasn’t much to be done. Other agencies were involved – the Coal Authority, the Environment Agency – but ultimately the decision about what to do rested with the golf club. They called in consultants, who came up with a few possible solutions; eventually, they decided to dig a trench around the fire.

I went to look at the part of the golf course beneath which the fire still burned. I ducked under a blue rope that fenced off an area of bare earth. Small clouds of smoke billowed from narrow crevices in the ground. I could hear the metallic clink of golfers teeing off nearby. Embedded in the soil were pieces of black coal and orange cinders. A thin row of trees, some charred by fire, lined the riverbank. Elsewhere, fire-damaged branches and blackened roots that had been pulled from the ground were scattered in heaps. After wandering through the fenced-off area, I walked towards the plumes of smoke. I crouched down and touched the hard dry earth next to the smoking fissures: it was hot to the touch, but not so hot you couldn’t keep your hand there for a few seconds. The fire must have been burning some distance from the surface. I breathed in, and inhaled the tarry reek of burning coal. The smell took me back to a time when open fires and coal-fuelled stoves were a fixture of many houses, including the one I grew up in. I felt the skin on my face tighten as it would in front of a fire on a cold night. The temperature in the cordoned-off area was warmer than the part of the course outside the rope. My lips felt dry afterwards, and for much of the rest of the day I had an almost dirty, itchy feeling, as though my skin had been coated in a thin layer of tar.

Thousands of coal fires burn above and below ground in countries around the world. They can be found in Australia, Borneo, Canada, China, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Russia and the US, on every continent except Antarctica. These fires range from the vast and apocalyptic to the small and relatively controllable. It’s thought that the oldest underground fire still ablaze is at Mount Wingen in New South Wales – commonly known as Burning Mountain – which has burned for around six thousand years. (A fire’s lifespan depends on the available fuel, and is extended significantly if it reaches a substantial coal seam.) In Germany, the coal seam fire at Brennender Berg has burned since 1668. A hundred years later, the young Goethe visited the site. ‘Thick fumes arose from the crevices,’ he wrote, ‘and we felt the heat of the ground through our strong boot-soles.’

It’s often difficult to know exactly what sparks underground coal fires. It can be some time before they make themselves known above ground, and, by then, it can be hard to pinpoint exactly when they started. With underground fires, cause and effect are split in an unnerving manner: you know that your garden (let’s say) is on fire, but you don’t know how long the ground beneath it has been burning, or who or what sparked the blaze. When I asked the then chairman of Ryton Golf Club, Paul Whittaker, how the fire under the course started, he could only tell me when they first became aware of it. Fires underground can be started by spontaneous combustion, if the right elements are present: the mineral pyrite, when combined with oxygen, produces heat, sometimes enough to ignite the coal. Lightning strikes can also spark coal fires, as can human intervention – for example, starting a blaze near deposits of coal.

The fire at Centralia, Pennsylvania has been burning since 1962 and shows few signs of stopping. Centralia’s fire is generally accepted as having been caused by sanitation workers setting fire to refuse near the entrance of a coalmine on the outskirts of the town. Firefighters attempted to stop it spreading, digging trenches to halt the fire or pouring a mix of sand, cement and ash into holes they had bored into the ground. But it continued to spread. More holes and trenches were dug. Projected costs spiralled. A dramatic solution was proposed: a pit, three-quarters of a mile long and as deep as a 45-storey building. It would cost $660 million, a sum greater than the value of the town’s properties. This plan was rejected. Not long after, the main road into town sunk eight feet in height and people started passing out in their houses from the carbon monoxide building up in their basements. The petrol tanks at the filling station started to heat up and, in 1981, a hole in the ground opened up beneath a 12-year-old boy, Todd Domboski, who clung to an exposed tree root until he was rescued. The town was evacuated; although a few people still live there, most residents accepted a federal buyout and moved elsewhere. (There were more than a thousand residents in 1962 and only ten in 2010.) More than six hundred buildings were demolished and the fire was allowed to burn on. In 2002, the US Postal Service revoked the town’s zip code. It has, perhaps inevitably, become a tourist attraction. A piece of much photographed graffiti sprayed on the buckled tarmac of Route 61 reads: ‘Welcome to Hell.’

In 1992, Glenn Stracher, a geologist, visited Centralia on a field trip. He had seen the fire on TV as a child, but witnessing it first hand was different. ‘I just couldn’t believe it,’ he told me. ‘It was geology happening in real time.’ When he learned that the fire had been burning for thirty years, he began to ‘do some calculations’ to work out the scale of pollution caused by such a blaze and the magnitude of its social impact. His visit to Centralia convinced him to concentrate his research on coal fires: his first published article was about the town, and he has gone on to investigate other fires around the world. He calls them ‘an environmental catastrophe’.

I mentioned to him a statistic I had read online: that surface and underground coal fires are responsible for 1 per cent of greenhouse gases worldwide. He told me that the figure was untrustworthy, just a ‘back of the envelope’ calculation – no one really knows what percentage of the gases such fires contribute. He said that smoke from coal fires contains around fifty compounds, many of them carcinogenic. We began talking about the fire I had seen at the golf course. Was it possible that it could continue indefinitely, or was it more probable that, as I assumed, it would burn itself out, after exhausting the fuel in the riverbank? Most coal spoil heaps, he said, do eventually burn themselves out – unless they meet a hidden coal seam. Then he asked: ‘Do you know if there are coal mining tunnels under the golf course?’

Old mine shafts and tunnels stretch beneath the streets of Tyne and Wear – the cities of Newcastle and Sunderland, and the town of Gateshead – and eastwards below the North Sea. It’s easy to forget that the mines are still there: ruined chambers from a past era, capped and partially filled. The last mine to close on the Durham coalfield was Monkwearmouth Colliery, which shut in 1994. At 1700 feet, it was for a time the deepest pit in Britain. Sunderland AFC’s Stadium of Light now occupies the site. At the centre of a roundabout next to the stadium is a huge miner’s lamp; a local invention, it was developed after the mine at Felling, nine miles to the north-west, exploded in 1812, killing 92 men. The blast was heard for miles around. Soot rained from the sky and the bodies of the miners lay scattered among the debris. The fire below burned for five days, and it was seven weeks before the dead in the tunnels could be retrieved. It was clear what had caused the explosion: the exposed flames of the miners’ lamps had met the ‘firedamp’ of the mine – flammable gases including methane. The tragedy led to the development of safety lamps that shielded the flame from the gas. One, invented by George Stephenson, who was born in Wylam, just across the River Tyne from the burning golf course, became synonymous with the area and was known as the Geordie lamp.

It has been some time since a mine has exploded, but underground networks make themselves known in other ways. In April 2015, a sinkhole opened on a street in Gateshead. It was fenced off, and after an investigation the Coal Authority confirmed that it was related to a mine that had been on the site, and said that it would be filled in. I went to the Coal Authority’s website and consulted the maps they held of the area. Much of Gateshead – the hills on which terraces had been built, including the street on which the sinkhole had opened – was marked as high risk for development, suggesting the potential for subsidence and collapse. After looking at the maps, ‘solid ground’ came to seem an empty phrase. Then I searched for indications of coal deposits.

Paul Whittaker had told me that, having looked at the evidence, Ryton Golf Club had decided that the burning area was once two lagoons next to the river which had been filled with discarded material from the mine and from the nearby ironworks. Based on this knowledge, they dug deep trenches around the fire, bulldozed the surface, and expected it to burn itself out. Looking at the Coal Authority map, I could see five dark pink lines worming their way across the golf course. According to the key provided, these lines indicated the presence of coal outcrops. Although he didn’t want to speculate, Stracher’s worst-case scenario – that the fire meets substantial coal deposits underground – suggested that it could burn on and on.

While it’s likely that the decision to isolate the burning section of the golf course and let the fire exhaust itself is the right one, as yet there’s no way of knowing. On the day I went to see the fire, after walking to the village of Clara Vale, I turned back towards the golf course. It was half an hour or so since I’d stood on the burning ground. The smell of coal tar still filled my nostrils. My skin was coated with smoke. I told myself, as I walked, that the haziness in the air was a result of my exposure to the smoke and that it wasn’t seeping imperceptibly from the ground beneath my feet. I looked around at the constructed landscape of the golf course – the man-made hillocks, the carefully arranged fairways and the artificially smoothed greens – and, at that moment, it all looked like fuel for a fire that I couldn’t yet see.

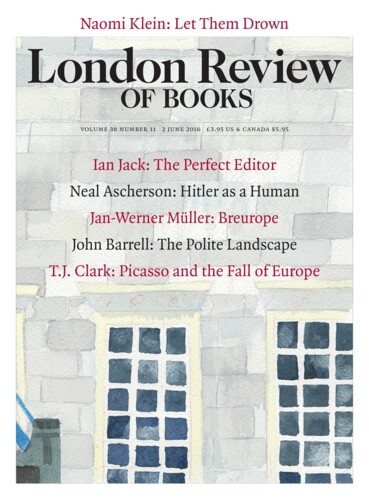

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.