Virginia Woolf’ s body was still undiscovered, lodged under Southease Bridge, when Margot Asquith, approaching eighty, published her personal tribute in the Times. The two women had been friends of a sort (Leonard disapproved): both were leading lights in famous circles of famous friends; both possessed a conversational brilliance liable to be iced with cruelty, an intensity threatening always to pitch into dangerous hilarity. Margot remembered her first sighting of Virginia, standing with Vanessa at a garden party at the Stephens’ house at Hyde Park Gate, both sisters beautiful, ‘dressed in white muslin, with grass-green ribands round their waists’. Perhaps in that moment, or more likely in this much later one, Margot identified that young woman, shrinking under the conquering gaze of Sir Leslie, as a younger version of herself, the one she dramatised in her novel Octavia, ‘brought up in an atmosphere of Scotch austerity’ but with ‘a spiritual side to her nature which … tugged at her like a kite at the end of a string’.

‘When I read of Parnell or Lasalle or smaller men who have arrested attention,’ Margot confided in her diary in her twenties, ‘I feel full of envy, and wish I had been born a man. In a woman all this internal urging is a mistake; it leads to nothing, and breaks loose in sharp utterances and passionate overthrows of conventionality.’ Her own achievements, first as a waspish socialite and later as an unsuitable political wife, seemed to confirm this as a bitter truth; but Virginia’s, now set out cleanly before her, showed that a woman’s genius, however embattled, could assert itself in lasting accomplishment. A sense of waste and loss – her own – breathes between the lines in Margot’s tribute; in her last letter to Virginia she told her that ‘at one time I was arrogant enough to think that I was the hostess at the festival of life, but that now I was not even a guest, and there was no “festival”. I added that when I died I hoped she would write my obituary notice … as that might make me famous.’ Still, Margot was Margot, and she couldn’t resist damning herself by telling the story of her first visit to the Woolfs’ house in Tavistock Square: ‘I did not realise at that time that when you are working you do not wear pretty clothes so I said to her: “Were I as beautiful as you, I would wear prettier clothes.”’

This memorial might be taken as an unwitting comment on ‘the Souls’, the gilded group of friends of whom Margot Asquith was in 1941 almost the last survivor, as well as on their governing mantra: to treat ‘light subjects seriously and serious subjects lightly’. Comprised principally of members of the Tennant, Balfour, Wyndham and Lyttelton families, connected and compacted by marriage and blood, the Souls spent upwards of four decades from the early 1880s ambulating between each other’s country homes and London town houses, playing intellectual parlour games and nibbling at the edges of philosophical debate, sometimes in the company of Oscar Wilde, Henry James, H.G. Wells and the Webbs. Today they are easily characterised as an unripened Bloomsbury Group: a celebrity clique composed of men and women unconventional in dress and conversation, literary and artistic, overlapping in their sexual commitments, but – also – aristocratic, imperialist, superficial and unproductive. They made a continuous show of effortless ability that is oddly suggestive of laziness: Cynthia Asquith remembered as a child waking early one morning and opening a window to see her uncle George Wyndham running circuits in the garden below: ‘Come out and join me,’ he shouted, ‘and then help me write an Aubade before breakfast.’

The ‘Bloomsberries’ can easily be made to seem startlingly contemporary in their priorities and perceptions, but the Souls have long been the prisoners of a pre-modern past, a world of transparent ease. The record of their conversation and activities conjures the atmosphere of the Naughty Nineties and the sunlit years of the Edwardian era: it is all dancing till dawn, pomade and cigarettes, white linen and straw boaters, bicycle rides and dips in the Serpentine. Their moniker, which they all professed to hate (while using it regularly), derived from their talent for a dreamy sort of introspection: ‘You all sit and talk about each other’s souls,’ Lord Charles Beresford said. Their children, buoyant on champagne and self-belief, were the first to turn against them. ‘Their minds are almshouses [for] outworn notions and wrinkled phrases,’ Raymond Asquith, Margot’s stepson, sneered. ‘We do not hunt the carted hares of thirty years ago. We do not ask ourselves and one another and every poor devil we meet “How do you define Imagination?” or “What is the difference between talent and genius?”, and score an easy triumph by anticipating the answer with some textbook formula.’ The First World War, which killed Raymond and many of his playmates, provides the inevitable coda to their story: spattering the beautiful dream with blood, rendering the past futile, and disarranging the future. In its aftermath came the collapse of the aristocratic system: servant trouble, death duties, new money, Ramsay MacDonald in Downing Street. Never such innocence again.

If the Souls are remembered at all it is partly because some of their number – Arthur Balfour, George Curzon and Wyndham – enjoyed major political careers, and partly because they generated an abundance of high-class anecdote, diligently archived by their descendants. They have, though, been rather unlucky in their champions, starting with themselves. In old age they struggled to justify their once axiomatic claim to distinction and were liable – except when the mask slipped, as Margot’s did – to exaggerate: Lady Frances Balfour believed they had ‘something of the effect of the Restoration on Puritan England’, though this was only ‘a rough analogy’. The difficulty lay in proving it when, as Lady Desborough mournfully acknowledged, the ‘laughter and delight’ had long since become ‘imponderable as gossamer and dew’.

Historians have continued to strain after the nature of their collective significance. Angela Lambert tried hard in 1984: ‘Many others who enjoyed the same privileges remained boring and boorish … It is not easy to be unfailingly charming, lively and original.’ Unfortunately, she did little to alleviate the suspicion that the Souls merely provide source material for aromatic period soap opera: ‘What meaningful glances must have flickered across the plates of kedgeree and kippers, between lovers whose warm bodies had only a couple of hours previously been clasped in each other’s arms.’ The latest attempt to invest the Souls with seriousness is Balfour’s World, Nancy Ellenberger’s interesting, interestingly flawed study, which makes a case for them as the originators of a new ‘emotional regime’. But were they really as serious as that?

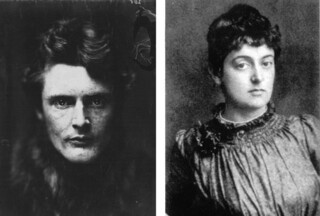

No one expressed the essential mood of the Souls better than Margot Asquith’s elder sister, Laura Tennant. In her portraits she is usually looking away, eyes lifted or lowered, but on Christmas Day 1883, aged 21, she stopped to consider herself:

What am I? A little woman with grey eyes with corners to them … & a nose with a lump in the middle, & a square jaw and a nameless complexion with small ears almost round & an ordinary neat figure & next to no legs. Is there anything in the outside? Well come in, what is there here?

A quick heart that beats for the children. A longing to understand – a great overwhelming ignorance – a sympathy for all that’s bad except cowardice and ungenerosity – a love of sky & hill & flowers – & a friendship with the shadows that sleep on the moors – with the birds & beasts – & the stars – an impatient irritable temper – a wavering erratic Faith and a passionate love for Symbol & the unseen & a fearful humble but Jesus faithful love of Thee.

The daughter of Sir Charles Tennant, the millionaire Glasgow industrialist, Liberal politician and newly minted baronet, Laura had shared an indulged, rambling upbringing with her many siblings at the Glen, their home in the Scottish Borders – a castellated fantasy mounted in parkland of astonishing beauty. In its nooks, corridors and attics, the young Tennants chattered unsupervised with guests, perfecting a culture of easy informality between the sexes. Laura – and later Margot – took something of the Glen’s bracing air and surprising intimacy to London society when they were triumphantly launched there in the early 1880s: Mary Elcho, Laura’s best friend and a prominent Soul, remembered ‘a plunge, a splash as of a bright pebble being thrown from an immense height into a quiet pool’. In the summer of 1883 Laura joined a private cruise to Copenhagen with an illustrious party that included Tennyson and Gladstone. Her tone – lively, candid, romantic – and her cheerful, provoking sympathy for ‘all that’s bad’ made her the toast of the trip. When she contemplated leaving early, Tennyson was appalled: ‘You are the life of the party – Gladstone and I will sign a round robin to prevent you going.’ No one had met a woman quite like her. This was because, four years earlier, in the privacy of her diary, she had decided to be not quite like other women:

However much I glory and love being a woman I have come to the sad conclusion after much thinking – that it is very hard being a girl. Oh! The whole thing, girls lives, girls proprieties, girls difficulties, the whole thing maddens me – and oh! How I long to be finished and done with it all … Am I very rebellious and unkind and unwise – no – I only long for something broader than I have, away with the horizon and those lines and rules that appear every minute. Can I break loose and be like no other girl, can I be free and pure and broad and loving?

Her attitude to relationships between men and women was forthrightly deviant: casting off a lover with whom she had shared passionate moments out on the heath, she recalled her initial hope that there ‘would be no room no necessity for self-control – for grown-up-ism and for all the triste chimère that usually stalk the lives of friendships and throttle them. I hoped we would just be completely natural, completely unconventional completely true and good.’ Still, she was not immune to the appeal of the obvious: among her admirers was Gladstone’s gorgeous nephew Alfred Lyttelton, the son of a baron and the first man to play both cricket and football for England. On New Year’s Day, 1885, Laura ogled him on the tennis court: ‘Alfred shines everywhere but at any game he positively dazzles one. How I love to watch his great strong figure clad in flannels & his mighty stroke that is meteorlike in its flight. He has perfect ease & perfect grace & is delightful to play with because of his fine generous temper.’

Alfred’s proposal, when it came before the gong at the Glen, was accepted (‘It was very short for I had to send him down to dinner’). They were married in May 1885, and Laura’s account of their subsequent lovemaking does little to dispel the sense of a charmed existence: ‘Oh! The bliss of his arms around me and the touch of his curls and the seal of his kisses on my hair and eyes and throat and the strong swift pulses beating everywhere and filling the air with fast music and filling my brain with deep draughts of thought-annihilation.’ She soon became pregnant, and gave birth to a boy in the spring of 1886. It was a harrowing delivery. She died six days later, aged 23. Margot saw her shortly before the end: ‘Her hair was hanging dragged up from her square brow in heavy folds upon the pillow. Her mouth was tightly shut and a dark blood stain marked her chin.’ (The child survived, only to die two years later of meningitis.)

Laura’s voice is so arresting – her rush of words so seemingly irresistible – that her sudden silence still induces a shock. At the time it was shattering. The Souls were born of an affinity discovered among those who had known and loved her, huddled against grief. At the core of the new gang were Laura’s husband, Alfred, her sisters Margot (now lured away from a red-cheeked hunting crowd, her distinctive broken nose the result of a fall from a horse) and Charlotte (Lady Ribblesdale), Mary Elcho and her brother George Wyndham, as well as intimates like Arthur Balfour and Frances Horner; joining them were Curzon, Harry Cust, Willy and Ettie Grenfell, Lord and Lady Pembroke, Violet and Henry Manners, and Wilfrid Scawen Blunt. A routine of long weekends – ‘Saturday-to-Mondays’ – was established, rotating between the splendid mansions at their disposal: favourites were Clouds in Wiltshire, Stanway in Gloucestershire, Taplow in Bucks. Together they developed a culture and ethos that Laura would have approved: beauty-loving, inquisitive and faintly mystical; thrilling to art and poetry; critical of social strictures and committed to an ideal of affectionate, confiding friendships between men and women.

It is easier to admire the Victorians for their hopeless (and so unavoidably hypocritical) attempts to match their behaviour to their conception of the good life – at least they tried – than it is to forgive their sense of fun, the amateur theatricals, fancy dress, practical jokes. In 1882, wintering at the Glen, Laura complained that ‘the house feels like a boys’ school … the constant locking of bedroom doors, blowing out of candles, booby traps, water jugs upset etc etc has a very small charm.’ The guest responsible for all the mischief was Herbert Gladstone, son of the prime minister, then aged 28 and already Liberal MP for Leeds, a future home secretary and the first governor general of South Africa. The Souls formed themselves in opposition to silliness of this sort, but also to the greater – because more deliberate and expensive – crudity of the Prince of Wales’s circle, the Marlborough House Set. When not partaking in shoots of warlike proportions, Bertie and his chums shared enormous banquets, a self-conscious philistinism and a cruel, caddish humour: on one occasion a bemused hostess was pressed to give the prince a tour of her house, up to and including her bedroom, where she found sprawled on the bed a ‘young donkey, fast asleep, with a little lace cap tied coquettishly on one side with pink bows’ (it had been encouraged to drink warm milk and champagne).

The Souls preferred talk – the more of it, and the more indiscreet, the better – in informal gatherings as well as around the dinner table, on a wide range of topics: ‘telling lies’, ‘love and matrimony’, ‘practising virtues if no one sees it’, ‘repeating things of your friends’, ‘ruthless conversation about bores’ and ‘If any one of us went mad what form would the madness take?’ One discussion centred on the virtues and which ones might be dispensed with:

Truth was done for, as a virtue which no moral being attempted to practise. Hope was declared a tiresome, weak-minded thing. Faith followed as a gift you either possessed without effort or were wrong to cultivate. Charity was left grudgingly. Mrs Horner wanted to do away with Justice but Lord Pembroke clung to it.

Happy hours were spent playing fiendish games of their own devising. Clumps was a version of twenty questions where the term to be guessed had to be an abstraction (‘the last straw’, for example, or ‘most dangerous of all’); Styles required players to write poems or prose in imitation of famous authors and the others to spot who was being parodied; Breaking the News involved impersonating yourself informing someone’s wife or best friend of their death, with everyone else trying to guess the identity of the deceased. A premium was placed on quick-fire, silver-tongued brilliance. Not everyone, apparently, was able to keep up: Wilfrid Scawen Blunt found Henry James

distinctly heavy in conversation and for a man who writes so lightly and well it is amazing how dull-witted he is. This is not only that he had no talk himself but he is slow to take in the talk of others. He tries hard, but he is always a little behindhand, but when he does find anything to say he spoils it in the saying.

Ellenberger does a good job of making us understand why any of this mattered. The activities favoured by the Souls gave the women of the group unheard-of licence to dispute with men, to be competitive, amusing and intellectually adroit, and to take from it an unguarded pleasure, free from the disabling fear of outside scrutiny. (The Souls also exercised in mixed company: golf, tennis and cycling were all preferred to the male preserve of the shoot.) Frances Horner and Edith ‘D.D.’ Balfour reduced everyone to hysterics when Henry Asquith portentously critiqued their literary pastiches under the impression they were works by Browning and Arnold. In an era when female humour was disparaged (Leslie Stephen wrote an essay claiming it didn’t exist) and women’s laughter perceived as an imposition on civilised company (Trollope believed a true lady would have ‘a great fund of laughter, which would illumine her whole face without producing a sound from her mouth’), these were not small triumphs. There is a joyfulness in Margot’s self-assurance, later eroded by the disillusionments of old age and too frequently maligned as arrogance: in 1883 she accurately described herself as ‘such good company, eccentric, atrocious flirt, cheek of the devil, fond of men and not quite dignified with them but rode very well, had great pluck, really clever … and her conversation to judge by men’s faces was very amusing very much so’.

All this noisy eloquence covered other, whispered conversations: the Souls’ debates and games of artifice were a form of release, providing opportunities to articulate nagging moral uncertainties and to propose in theory experiments in living already undertaken in practice. The perceived impossibility of divorce – sustained by the fear of social death, but also by carefully managed expectations (‘You should marry in spite of being in love, but never because of it,’ Margot was told by Lord Dufferin) – created space within mutually unsatisfying relationships for the exploration of alternatives. Among the Souls this duality expressed itself in the unspoken understanding that ‘each woman shall have her man, but no man shall have his woman.’

George Wyndham enjoyed a lengthy affair with Lady Plymouth, while the scandalously handsome Harry Cust, Tory MP and editor of the Pall Mall Gazette, had liaisons with Violet Manners, later duchess of Rutland – Lady Diana Cooper was the result – as well as with George’s sister Pamela, who protested to alarmed family members that ‘he says “How do you do” as if it was “you are the Soul of my life,” but he is unaware of this, I really believe like people who clear their throats continually.’ The most famous case was that of Arthur Balfour and Mary Elcho, whose affection for each other predated her marriage to Hugo Charteris, Lord Elcho, and persisted for the rest of their lives. Balfour’s emotional reticence had prevented him from pressing his claims before her engagement – ‘You were afraid, afraid, afraid!’ Mary scorned – but they quickly resumed their intimacy, encouraged by Hugo’s own affair with the duchess of Leinster. Decades later Balfour and Mary’s relationship was well-understood by their friends, who turned a blind eye to misspent mornings involving birch-rods and peppermint grease: ‘Two hours is what I like,’ Mary wrote in 1904, by which time Arthur was prime minister, ‘one for boring things and one for putting you in yr place … on yr knees at my feet.’

Not all the ‘special friendships’ among Souls were so uxorious. One destabilising presence was Wilfrid Scawen Blunt, poet, agitator and Arabist, possessed of legendary powers of attraction (in his fictionalised version of Blunt’s affair with Lady Gregory, Colm Tóibín has her think of him as like a ‘goose stuffed at Christmas’). At this distance he appears a faintly disturbing but almost ludicrous figure, a sexual predator who was also a sentimentalist. In 1891, Margot, aged 28, still unmarried and impatient of convention (‘Why should I appear indignant when I am kissed or angry when I am fondled? Its [sic] humbug when I like it’), asked Blunt, nearly thirty years her senior, to relieve her of her virginity in her childhood bedroom at Glen. ‘At about midnight,’ Blunt recorded in his diary, ‘I found her there, very sweet and gentle in her little virginal bed … What a treasure to have won from Time!’ Four years later, he even succeeded in temporarily seducing Mary away from Arthur. The fact that she was the daughter of Madeline Wyndham, his cousin and ex-mistress, only added to her appeal: ‘She reminds me so much of her mother, whom I also loved thirty years ago … she is an ideal woman for a lifelong passion and has the subtle charm for me, besides, of blood relationship.’ On a trip to Egypt, camping in the desert, he claimed her as his ‘Bedouin wife’, delighting in the ‘naked tell-tale footsteps in the sand’ leading from her tent to his. Returning home pregnant, Mary confessed all to her husband. ‘If it had been Arthur I could have understood it,’ he told her, ‘but I cannot understand it now. I forgive you but I shall be nasty to you.’ The child was passed off as Hugo’s (his principal anxiety was that the family of the duchess of Leinster, whose deathbed he had attended while Mary was abroad, would judge him for an overhasty sexual reunion with his wife), and Arthur returned to his familiar place. Meanwhile Blunt and Mary’s daughter imbibed the important lesson of her birth with her mother’s milk: many decades later, on the eve of her own daughter’s wedding day, she told the happy couple that ‘Of course you will never have affairs because you won’t be able to afford enough servants.’

The juxtaposition of the Souls’ ‘pleasurable, informal, friendship-building sociability’ with their ‘secret relationships, hidden emotional agendas and stifled anxieties’ is central to Ellenberger’s book. What is unexpected is the further connection she makes between these country house intrigues and the remaking of British politics at the end of the 19th century. The further expansion of the franchise – the 1884 Reform Act doubled the electorate to nearly six million – was undoubtedly the most significant of these. Democracy wasn’t only a matter of having the vote: it was also something that was, and had to be, experienced. It was an orientation of politics towards a mass public, constituted and symbolised by new sorts of connection, insight and interaction. Party leaders were now expected to demonstrate their accessibility and accountability to voters at all times, traversing the country delivering speeches (often to audiences in the tens of thousands) and dedicating themselves to the service of local party organisations. The success of their efforts depended on the existence of a properly national media, linked up thanks to the railway and the telegraph and staffed by journalists minutely interested in the appearance, personalities, homes and habits of politicians: ‘In these days private life [is] … invaded, and no man [can] … fill a public position without feeling that his private life [is] … no longer his own,’ Lord Rosebery complained. Press coverage of politics presented affairs of state in newly intimate, personal terms, as popular spectacle and public entertainment. Winston Churchill remembered that ‘working men whether they had votes or not followed [politics] … as a sport.’

It is in this wider perspective that Arthur Balfour emerges as Ellenberger’s central character. Her subject is his ‘world’ in the sense of his social geography, but also the changing British imperial polity that was his inheritance as a governor of men. In the years during which he was enjoying his Saturday-to-Mondays with the Souls, he was also establishing himself as one of the most powerful and popular politicians of his day: notorious as an authoritarian chief secretary for Ireland in the late 1880s, he was the Conservative leader of the House of Commons for most of the 1890s, becoming prime minister in 1902. Rather than seeing these two aspects of Balfour’s life as distinct, Ellenberger wants us to see them, rightly, as fundamentally connected. Her suggestion is that the demeanour he developed and deployed as a Soul – a bantering, smiling, shifting façade, concealing depths of thought, feeling and calculation – made him the archetypal political modern, allowing him to ‘handle his own self-presentation and to manage his image in a political world where “public relations” was in its infancy and political consultants were non-existent’.

The problem lies in Ellenberger’s strict conception of the ideal imperial statesman in the Fin de Siècle: ‘An inviolate inner self maintained its secrets in order for the politician to soothe, bluff, entice, compromise and evade as public need required. [The] … virtues of honour, integrity and purity of motivation were disappearing among public men, sacrificed to … levity, instrumentality and concealment.’ Most political historians will be surprised to see these latter qualities adumbrated as new in the annals of government. Gladstone, whose effortful sincerity Ellenberger cites as representative of the passing generation, was throughout his long career attacked as a pious fraud (including by Balfour), and in his last years could not conceal his desperate ‘struggling, striving, writhing, clutching’ for power from his wincing colleague John Morley.

The real challenge facing leaders in a media democracy was – as it still is – to focus minds. In 1886, the Pall Mall Gazette stated matter-of-factly that to be ‘interesting’ was the ‘one quality which in these days is essential to a democratic statesman’. Ellenberger, for all her emphasis on the necessary fact of an outward-facing persona, is curiously uninterested in the impression Balfour made on the public. In her determination to paint him as a ‘master of deception’ she fails to see that whatever he was hiding was the least important thing about him. Balfour understood this, once telling Margot: ‘I do not think you quite realise what a small fraction of what we call personality can really be said to depend upon the person. Personality … really means the power of striking the popular imagination: and this is in every case as much due to favourable accident as to inherent capacities.’ The popular view of Balfour was nothing to do, as Ellenberger thinks, with ‘the charisma of the mysteriously self-contained’. Instead, the public fairly lapped him up as a handsome ladies’ man, charmingly informal and lighthearted; the newspapers loved to publish pictures of him on his bicycle, or striding out on the golf course. For precisely these reasons, Balfour was the perfect representative of the dominant Toryism of the 1890s, strongly associated with the defence of popular leisure and contrasted with a prim and pursed-lipped Liberalism. He was endowed, according to one journalist, ‘with the happiest of all faculties – the power of approaching his most serious tasks with the air of one about to engage in a game’. If the Souls must be freighted with historical significance, it was thanks to them that Arthur Balfour was formed as an attractive, vote-winning personality. In 1898, W.T. Stead noted that Balfour was ‘the one political man in Britain everybody likes’.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.