James Merrill has in Langdon Hammer the biographer he would have wished for: intelligent, appreciative, sympathetic, thorough, a first-rate reader of the poems, and an excellent writer to boot. Merrill would have hated to be the subject of a plodding biography. He was all about stylishness and elegance, in poetry and in life. But James Merrill: Life and Art shows that you should be careful what you wish for. At 809 pages, not including a hundred pages of notes and index, this biography is about the size of The Brothers Karamazov, recounting in exhaustive detail the not terribly eventful or interesting life of this least Dostoevskian of writers. Poets’ lives are seldom eventful or interesting. There’s a great deal of looking out the window, pacing around, reading, writing, drinking, gossiping, complaining, especially about money and neglect, and more often than not ill-advised romantic attachments. Though money, or the want of it, was not among Merrill’s complaints.

Merrill seems to have believed that his life was an extension of his poetry, both of them works of art. His own life, or his life recalled, was his principal theme, and Proust, with whom he fell in love during his first year at college, his principal model. The considerable archive he donated to the Olin Library at Washington University in St Louis includes not only drafts of poems and letters but notebooks, calendars, guest books, along with more than fifty years’ worth of diaries and journals, most of which no one but Merrill had ever read. He encouraged and in some cases paid friends and lovers, of whom there were legions, to donate letters they’d received from him to the Olin archive. Hammer mines this trove with tireless ardour.

Merrill’s 2001 Collected Poems is much the same length as the biography, at 885 pages. A companion volume, The Changing Light at Sandover, which comprises three books and a 37-page coda, incorporates ‘supernatural communication’ with assorted spirits including various deceased friends, Auden, Plato and a peacock called Mirabell, all of it recorded with the help of Merrill’s longtime partner, David Jackson, during twenty years of séances using a Ouija board at their home in Stonington, Connecticut. This volume tips in at 560 pages. Merrill also wrote novels, plays and two memoirs. Born to enormous wealth, he had little to distract him from his writing apart from endless rounds of socialising and travel. His father was Charles ‘Good-time Charlie’ Merrill, cofounder of Merrill Lynch, who earned his moniker through prodigious accumulation of money and women.

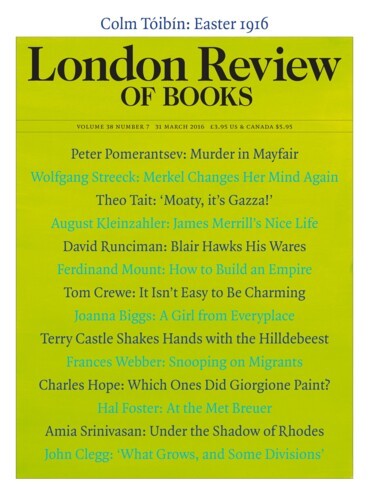

James Merrill was at the forefront of American poetry in the 1970s but is seldom read today. Despite this, he is a significant poet, preternaturally gifted, a master of form (metre and rhyme) and design, and often elicited comparisons with Mozart, who liked to boast that he ‘pissed’ music. Busoni would be a better comparison with his huge technical skill, high surface finish and complexity of design, much of it gratuitously decorative, and often with not terribly much going on underneath. Both had a large gift that was also a vice, one Merrill was certainly aware of, occasionally warred against, but usually succumbed to. Hammer, whose appreciation of his subject tends to lapse into worship, does not shy away from Merrill’s virtuosity and the poet’s own quarrel with it. Hammer met Merrill when, as a student at Yale, he was designated to pick up Merrill from Stonington and drive him to a reading. He was thoroughly charmed by the man whose life he now, as head of the English Department at Yale, exhaustively records. Hammer finds Merrill to be a wonderful, even exemplary man. It’s hard to disagree: he was brilliant; his capacity for friendship and love, sexual and otherwise, appears to have been boundless; he was supremely generous to friends, and through the Ingram Merrill Foundation he established in the 1950s, to artists and arts organisations.

I never met him. I missed him by a semester when he was teaching at the University of Wisconsin in the spring of 1967. By all accounts, even his own, he wasn’t much of a teacher, but was a delightful presence. One of his students that term, Stephen Yenser, became not only a lifelong friend but one of Merrill’s very best readers, and co-editor, with J.D. McClatchy, of an excellent though overlong 2008 Selected Poems. Reading Merrill at length can feel like being trapped in endless rooms full of Ming Dynasty black lacquer furniture with mother-of-pearl inlays, and flowering begonias painted on, along with birds and butterflies alighting on pomegranate stems – it’s exquisitely fashioned, but makes you want to find the sanctuary of a Shaker meeting hall where one might sit on a hard wooden bench and stare at not very much at all.

It didn’t come out of nowhere. In one of his most restrained, and most successful poems, from the sonnet sequence ‘The Broken Home’, he provides this portrait of his father late in life:

My father, who had flown in World War I,

Might have continued to invest his life

In cloud banks well above Wall Street and wife.

But the race was run below, and the point was to win.Too late now, I make out in his blue gaze

(Through the smoked glass of being thirty-six)

The soul eclipsed by twin black pupils, sex

And business; time was money in those days.Each thirteenth year he married. When he died

There were already several chilled wives

In sable orbit – rings, cars, permanent waves.

We’d felt him warming up for a green bride.He could afford it. He was ‘in his prime’

At three score ten. But money was not time.

‘I am a mixture of Santa Claus, Lady Bountiful, the Good Samaritan, Baron Richthofen, J.P. Morgan, Casanova. I am tender as a woman, brave as a lion, and can fight like a cat.’ This is the way Charles E. Merrill described himself. In truth, his considerable generosity notwithstanding, he was a rapacious monster. Merrill père can probably be credited with the introduction of the chain store – he developed the Safeway supermarket chain and was the underwriter for McCrory’s five and dime stores as well as the Kresge chain, the ‘ancestor of Kmart’ – and regarded himself as a great benefactor of the common man. When he wasn’t working he was chasing women, who seem to have been pleased to be caught by the diminutive tycoon. ‘He was the banker as Jazz Age celebrity,’ Hammer writes, ‘in plus fours or a double-breasted Van Sickle suit, a confessed hedonist and the hardest worker going.’ James, his only child by his second marriage, to Hellen Ingram, seldom saw his father. His parents separated when he was 11 and divorced when he was 13; the break-up traumatised him.

When he was six, he wrote ‘Looking at Mummy’:

One day when she was sleeping

I don’t know who

But it was a pretty lady

That knows me and you.So, one day when she was sleeping

I took ‘Mike’ a-peeping

The ‘do-not-disturb’ was on the door.

And I looked around the room and floorThen I looked to the bed

Where that pretty head lay

And the hair was more beautiful

Than I can say.

It’s possible that Merrill had some help with this composition from the subject of the verse, who ‘played rhyming games with her son when he was small’ and ‘wrote doggerel to please family and friends’. Mike was the family’s red setter. Merrill’s mother was quite as formidable as her husband. Like him, she grew up in Jacksonville, Florida. After graduation she became a journalist, the society editor of Jacksonville’s evening newspaper. Soon, she was putting out her own weekly social chronicle; she ‘sold ads, wrote the copy, corrected proof, pasted up the “dummy”, rolled the magazines for mailing and carted them to the P.O. to send them on their way’. Miami was becoming a big tourist destination and as Florida grew so did her paper, the Silhouette. During the summers, when society events slowed down, she went to New York to study journalism and fiction-writing at Columbia. She befriended one of her teachers, Condé Nast, publisher of Vanity Fair and Vogue, and was soon attending his Manhattan parties.

In 1924, having heard that Charlie Merrill had separated from his first wife, Hellen wangled an interview with him. Charlie was fascinated. She was a professional, business-savvy and cultured, and she smoked and drove a car; she was not only a very lovely young woman but a modern one. It was a love match, and it made perfect sense. Charlie sealed the deal when he had an ‘orange tree, heavy with fruit’ delivered to Hellen’s aunt, who had come to visit. As Hellen later put it, ‘No Southern woman could resist an orange tree in New York.’ James Merrill’s half-sister Doris would remember Hellen as a woman perpetually at her desk writing thank you notes and invitations. Hellen and Charlie sought out New York society and, as with most else, conquered it. Throughout his life, Merrill would be intimidated by, if admiring of, his mother and her pluck. From ‘The Broken Home’, written 32 years after ‘Looking at Mummy’:

One afternoon, red, satyr-thighed

Michael, the Irish setter, head

Passionately lowered, led

The child I was to a shut door. Inside,Blinds beat sun from the bed.

The green-gold room throbbed like a bruise.

Under a sheet, clad in taboos

Lay whom we sought, her hair undone, outspread,And of a blackness found, if ever now, in old

Engravings where the acid bit.

I must have needed to touch it

Or the whiteness – was she dead?

Her eyes flew open, startled strange and cold.

The dog slumped to the floor. She reached for me. I fled.

The ‘broken home’ was 18 West 11th Street, a particularly lovely block of brownstones. The address became famous when the house was accidentally blown up in March 1970 by the Weather Underground. Merrill wrote a poem about the incident:

In what at least

Seemed anger the Aquarians in the basement

Had been perfecting a device

For making sense to us

If only briefly and on pain

Of incommunication ever after.

Charles Merrill’s grandest and most favoured residence was the Orchard, a thirty-acre estate in Southampton on Long Island, which he bought for $350,000 in 1926. Stanford White, a friend of the original owner, another Wall Street baron, designed the interior and ornamental bits in the garden. White was later shot by a jealous husband, a grace note that especially delighted Charlie. As a child Merrill spent summers here with his half-brother and sister from his father’s first marriage. ‘This was the formative setting of Merrill’s childhood,’ Hammer writes. ‘It showed him that a house could be a self-enclosed world, expressive of its owner. It left him both attracted to and resistant to everything that was grand.’

While Merrill’s adulthood was filled with privilege, fun, friendship, sex and poetry, his childhood appears to have been unhappy. A sickly child with poor eyesight, whose thick glasses affronted his mother, he was coddled by servants but largely neglected by his parents and shunted from school to school as Charlie moved restlessly between his houses in New York, Palm Beach, North Carolina, Southampton and Tucson. In 1933, when Merrill was seven, his parents hired as his governess a woman named Lilla Howard whom Jimmy came to love. She seemed to have exotic European origins and, though not French, was to be addressed as ‘Mademoiselle’. Merrill called her Zelly. She ‘gave him his first book of foreign postage stamps, and fussed over his ever expanding collection with its scent of faraway places … she copied prayers and poems for him to read and memorise. She stitched costumes for his marionettes.’ He was a devoted puppeteer and would remain so, literally and figuratively, throughout his life. Merrill’s older half-brother, Charles, who rather resented his pampered relation, remembered Zelly as ‘a mix of intellectual seriousness and kindness, which Jimmy wasn’t getting from Hellen’.

When he turned 13, his parents now divorced, Merrill was sent off to board at the Lawrenceville School in New Jersey. He was a pudgy boy, hopeless at sport, bespectacled, brilliant in class, aloof and distinctly effeminate. He of course immediately became the favourite subject of the kinds of torture boys inflict on one another in these environments. A favorite sport was being ‘depantsed’, which involved the boys stripping Jimmy ‘naked, then rubbing his penis and anus with stinging peppermint oil’ and then forcibly masturbating him. The boys ‘whistled when Jimmy crossed the campus with the swishy, hips-first walk the boy was developing’. But Jimmy, finally, was Charlie Merrill’s boy, and found a way to put a stop to his persecution. When cornered one day by a posse of louts, instead of being forcibly depantsed, he took his own trousers off in the teasing manner of a striptease. That put paid to the business. Merrill would later write that this was his first experience of ‘hate’.

Lawrenceville in the early 1940s was no different than other boys’ boarding schools in its rituals of hazing. What was different was the calibre of the education. Merrill made his first friend, a Jewish boy called Tony who wore pink and mauve cashmere sweaters, and who had ‘an imitation upper-crust drawl and a lisp’. He tried his hand at writing poetry. He made more friends. He threw himself into theatrical productions, always plumping for the female roles, anything to put on a frock. From being an object of ridicule and abuse, he became an exotic character. His father was interested, from afar, in Jimmy’s development as a poet, and remained so. In 1942 he paid for the publication of a small collection of poems and stories entitled Jim’s Book, which included a poem called ‘Mozart’:

With suavely polished joy, restrained exuberance,

The violin sings its bland Rococo harmonies,

Smoothly fashioned phrases soaring to the skies

In sinuous silver trills of sham insouciance.Music free from passion, passionately played,

Plumed with cool perfection, powdered with despair!

Each delicious flourish daintily debonair,

Purity on paper, brilliance on brocade!

Already, at 16, he was engaging with the dilemma he would struggle with for the rest of his writing life. As Hammer puts it, his work puts ‘artfulness and emotion at odds with each other: the strong feelings they involve – grief, moral outrage – are put out of reach by the conspicuous skill that evokes them.’

He enrolled at Amherst College, as his father wanted. Charlie was an Amherst alumnus and a major benefactor. Jimmy usually went along, best as he could, with the wishes of his father, a distant but not malign presence in his life, in contrast to his overbearing mother. His half-brother Charlie had insisted on going to Harvard, which enraged the old man. Merrill enlisted in the army in 1944. His bad eyesight kept him in the typing pool in New Jersey, almost certainly no hardship to the Allied cause. He was mostly bored, read and reread Proust, and mooned over one of his bunkmates. All that came of that was the bunkmate receiving an inscribed copy of Rilke’s poems around the time Merrill was discharged, abruptly, in January 1945 (almost certainly as the result of string-pulling by his father).

Over lunch in Amherst in September 1945 Merrill met Kimon Friar, the most influential person in his young adult life. Merrill was to spend a great deal of time, not least in his novel and memoir, exorcising his influence. Friar was a visiting instructor at the college and director of the Poetry Center at the 92nd Street YMHA in New York. Born on an island in the Sea of Marmara to Greek parents who emigrated to Chicago, he was, at 33, 14 years older than Jimmy: ‘short, wiry and dark … a high-minded, charismatic man of letters and an unabashed self-promoter’. (Hammer, to his credit, is protective of his subject and seldom refrains from discreetly revealing disapproval.) Merrill asked Friar to have a look at some of his poems. Friar groaned but when he finally agreed to look he was flabbergasted:

I was thunderstruck … I called in Merrill and said: ‘You’re already a superb poet. I cannot, of course, make anyone a poet who isn’t one initially: I can only teach you all the techniques I know during the remaining time I have here … You must be willing, in this short period of eight months or so, to give yourself over to my dictatorial direction … I shall set you exercises in all forms of poetic techniques and, at the same time, commission you to write for me about three poems a week embodying the lesson. I’ll set the themes, the stanza forms, the metres, the rhyme schemes, and orchestration, everything … What do you say?’

‘Try me!’ Merrill replied.

Soon afterwards the two became lovers; it was Merrill’s first real homosexual affair. ‘I have been taught to love,’ he wrote operatically in his diary.

His mother found out what was going on, after opening a letter Merrill had sent Friar, and called Charlie, who summoned a family war council. The notion was floated of hiring a mobster to have Friar ‘rubbed out’. A ‘more seemly’ suggestion, as Hammer puts it, was to engage the services of a ‘woman of loose reputation in Southampton, with an interest in the arts, who might be paid to introduce Jimmy to the pleasures of female flesh’. All that came of it was a call to Friar from Hellen telling him to cut it out, now.

Needless to say, that served only to inflame the romance. Merrill was enchanted by Friar’s being Greek and by the ancient Greek notion of eromenos, ‘the mentor and lover who helps the erastes, a beautiful youth, to discover the passion for knowledge through their erotic relationship’. Friar introduced Merrill to Cavafy’s love poems. Merrill had studied ancient Greek, now he was learning the demotic. Finally, Hellen’s disapproval was too much for Merrill and he bailed on his lover. He couldn’t ‘cope’, he said, so he found a new ‘friend’ for a while, and then another … He moved to New York and started on a lifelong round of dinner parties and soirées. He turned 21 and the enormous trust fund that Charlie had set up for him and the rest of his children kicked in. He was suddenly a very wealthy young man.

This was a mixed blessing. He would always wonder, as the rich I suppose do, who his real friends and lovers were and who was in it for the free ride. But the money did allow him to live the sort of life he would have chosen for himself, and it wasn’t an especially grand one. In 1956 he bought an ordinary enough three-storey house in Stonington. He also travelled, of course, and bought a house in Athens, and in the late 1970s a place in Key West, but he was keener on giving money away than spending it on himself. He lived to read, write, travel, go to parties, pick up young men, fall in love with this one and that.

He visited Greece for the first time in 1950. Hammer’s description of Merrill’s first impressions of ‘Athens in its legendary “purple dusk”’ – and the excitement of the visit as a whole – may well be the best part of the biography: ‘Merrill was released then into the sensory revelation that was Greece. For the first time, he heard nightingales sing and peacocks cry. He strolled in Athens’s “extraordinarily lovely” gardens: “Lemon and bitter orange flowering, the air filled with their odours – a sense of wafting that I have never before known.”’ Friar, with whom Merrill had kept in touch, was his guide; there was a growing unease between them, but the trip itself was exhilarating. Something about Greece, and not merely the very available young men, refreshed and exhilarated him, and he produced much of his best work there.

Merrill met David Jackson after a performance at the Artists’ Theatre in Greenwich Village of a play of Merrill’s called The Bait. During a soliloquy ‘heads swivelled as “Arthur Miller and Dylan Thomas … stumbled out,”’ ‘passing judgment’, as Hammer puts it, ‘with their feet’. ‘I learned what Mr Miller, with uncanny insight, had whispered in Dylan’s ear shortly after the curtain rose,’ Merrill wrote years later in his memoir A Different Person, ‘You know, this guy’s got a secret, and he’s gonna keep it.’

Jackson’s voice was the first thing Merrill noticed. He was from somewhere else, somewhere in the American West. Lead, South Dakota was in every sense about as far as could be from West 10th Street, where Merrill had moved on his return from his trip to Greece. David was fair-haired, strongly built, heterosexual in manner and sported a wedding ring. He was the son of native South Dakotans, his father a failed businessman who moved his family to southern California in the 1930s, like so many others from that part of the country. David grew up in a down-at-heel part of LA until after the war the family moved to a new ranch house in Tarzana in the San Fernando Valley. This was where, in 1954, David took Jimmy to introduce him to his parents: George, ‘an irascible husband and father who grew meaner, even brutish in old age’, and Mary, a ‘forbearing’ mother who was ‘funny, sweet, sociable, and a heavy drinker’. She also liked to tell stories and embellish, a trait her son seems to have inherited. (Among David’s fibs were that he’d won the Purple Heart, that his uncle owned the magazine Popular Mechanics and that his father had founded an airline.)

Jimmy and David rented a Volkswagen Beetle for the trip out west. In one of the most amusing scenes of the book – exactly the sort of scene a less comprehensive biographer would omit – the couple arrive in Tarzana. Jimmy offered to make dinner for the family, who would have much preferred dining out: he banished David’s mother from the kitchen, ‘stood at the stove and produced the meal while wearing lavender knee socks and shorts and a lavender striped shirt. Then, at the table, he gobbled and sucked.’ David’s wife, Sewelly, had also turned up for the gathering. (David and Sewelly had met and married in a heat at college and quickly discovered they were both gay but remained great friends.) Sewelly remembered that ‘Jimmy made so much noise – no one had taught him how to eat!’ Later that evening Jimmy, David and Sewelly, whom Jimmy immediately adored, went off to Laguna Beach, checking into a ‘superdelux’ motel. They found a bar where they proceeded to get tight. They drank some more back at the motel and ‘fell into one bed’. The next day, Merrill wrote, the three of them ‘greeted the morning with all our old vigour, reading the funny papers on the little cliff where they served breakfast’. ‘The photos from that Sunday breakfast,’ Hammer adds, ‘shine with mischief. With the Pacific crashing behind them, the sun beating down, and the comics spread out on the table, they made a lively, unlikely trio: two brand-new friends, two male lovers, and a devoted husband and wife.’ Sewelly would remain one of Jimmy’s favourite people.

Episodes like this are the pay-off of biographical exhaustiveness. Now for the costs. We learn that Merrill ‘had developed a painful haemorrhoid, which resisted Miss MacHattie’s remedies. So Jimmy consulted the physician attending his father in Rome, Dr Albert Simeons. A British-born endocrinologist with high-society clients, Simeons was, Jimmy found, “a very charming man”.’ Simeons recommended surgery and Merrill consented, though he was nervous. He’d been reading the Purgatorio, and viewed the operation as a spiritual trial – which it would turn into before he left hospital. ‘As they chatted prior to surgery, Simeons soothed his young patient, playing Virgil to this impressionable Dante, by dispensing consoling wisdom.’

At least half of this biography wastes the reader’s time with this sort of kapok. This raises a larger question: what is the function or purpose of such a detailed biography of a poet? Does it bring us closer or tell us more of what we would like to know about the work? I think not. Three or four top-flight essays, and they’re certainly out there, perform that service far better. Late in life Merrill, who simply pretended that modernism never happened, read Hugh Kenner’s The Pound Era with great interest. Merrill had no prior interest in Pound and the ‘heave’ that broke the back of the pentameter. His view was: why bother? The pentameter was just fine. But The Pound Era (at only 561 pages) is an intellectual biography, not only of the man but of the milieu he worked and developed in, and at no point discusses issues to do with the poet’s digestive tract. Kenner succeeded in bringing Merrill to read Pound seriously for the first time. I find it unlikely that Hammer, who makes very bold claims indeed about Merrill as a major figure in modern English-language poetry, will succeed in altering the opinion of the Merrill sceptic over the course of his heroically thorough undertaking.

Merrill continued to write and travel and entertain for the rest of his life, garnering prize after prize along the way. Did he deserve all the praise and prizes? Probably not, but more than most who win these awards. With its complex surfaces, formal dexterity and irony, his poetry fitted the aesthetic priorities of the New Criticism, the prevailing literary theory of the time. All his collections contain superb individual poems, but for my money his best poetry is buried in his first Ouija board collection, The Book of Ephraim, but can only be found if one is prepared to wade through all the inane, CAPITALISED utterances of friends and luminaries from ‘the other side’. His voice is more intimate in these poems:

My downfall was ‘word-painting’.

Exquisite Peek-a-boo plumage, limbs aflush from sheer

Bombast unfurling the troposphere

Whose earthward denizens’ implosion startles

Silly quite a little crowd of mortals

– My readers, I presumed from where I sat

In the angelic secretariat.

The more I struggled to be plain, the more

Mannerism hobbled me. What for?

Thom Gunn, in an enormously admiring essay, remarks of his earlier work: ‘His poetry has been, typically, personal and anecdotal, but the narrator was most comfortable as an almost anonymous observer … least comfortable at the centre of the poem where … the treatment becomes positively rhetorical. The rhetoric amounts to a kind of withholding, but I am not sure of what.’ The verse of the Ouija board poems is freer; the use of the board seems to have helped liberate Merrill from himself. He was an extremely controlled poet and human being. He struggled to be less so. Greece also served him in this fashion.

James Merrill died in February 1995 of an Aids-related illness. He concealed his illness from all but his closest friends and handled his situation with as much dignity and consideration to others as he was able to summon, even if he felt ‘beleaguered by the number of old friends from far places’ who visited him towards the end. That was who he was. The poet Frank Bidart, one of his older friends, is quoted near the end of Hammer’s book: ‘He was infinitely accomplished, preternaturally gifted – the greatest rhymer since Pope – capable of doing anything on the page, with a divine assemblage of sound and movement.’ Money, Bidart goes on, gave Merrill the power to get ‘not everything he wanted in life, but a lot [of it] … and Jimmy was very aware of how lucky he was. Now all of a sudden he wasn’t.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.