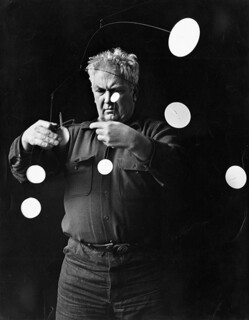

Sculpture conventionally does one of two things; it either creates space by carving, or creates volume by modelling. Once the material has been cut back or built up, a statue, as the word implies, is static in its relationship to space. Moving sculpture occupies space in a variable way and it has its own history, from devotional objects in the late Middle Ages fitted with clockwork to make Christ’s blood appear to flow, to the lion which Leonardo da Vinci is said to have made, which walked and opened its breast to offer its heart to the king of France. When clockwork was cutting-edge technology moving figures were taken seriously; as it became commonplace it was relegated to the world of novelty, of singing birds and dancing dolls, and finally to toys, all of which, as Penelope Curtis writes in her introduction to Alexander Calder: Performing Sculpture (until 3 April), ‘exist beyond the confines of “fine art”’. Calder’s reputation centres on the fact that he reintroduced moving sculpture to high culture by inventing what his friend Marcel Duchamp named the ‘mobile’. Yet some of the anxiety signalled by all those inverted commas is still perceptible in this thoughtful and delightful exhibition, the largest ever of Calder’s work in Britain.

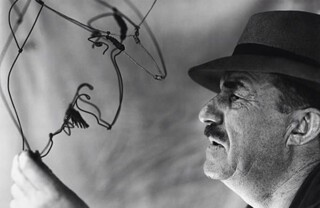

Calder was born in Lawnton, Pennsylvania in 1898. His mother was a painter and his father a sculptor but Calder took a degree in mechanical engineering before going on to drawing classes in New York and a job as an illustrator for the National Police Gazette. For some reason the Gazette commissioned him to spend two weeks drawing Barnum and Bailey’s Circus. ‘I was very fond of the spatial relations,’ he recalled. ‘I made some drawings of nothing but the tent … the vast space – I’ve always loved it.’ In 1926 he went to Paris and began making his own circus, the Cirque Calder, with demountable ring and numerous acts. The performers were wire figures, mostly about six inches high, some stuffed, such as the sword swallower into whose velveteen body the sword fits almost to the hilt, others just outlines, like the pair of conjoined acrobats, one of whom springs up to do a handstand over his partner’s head. The figures are pared to the essence but brought alive by Calder’s engineering skill. Pins set asymmetrically in two wheels make the kangaroo bounce as it goes along. When the knife-throwing act goes wrong – the circus has its dark side – two stretcher bearers appear, their official status marked by a busy-and-important walk.

None of the figures moves independently. When Calder performed the circus he lifted the acts in and out of the ring, pulled them on strings, flicked them onto tightropes or simply held them in position. They didn’t always work. If an acrobat’s somersault failed to land him on the galloping horse, Calder would repeat the performance until it did. A film made in 1955 by Jean Painlevé (a DVD is available at Tate) shows the whole thing lasting about forty minutes.

Calder pays almost no attention to his audience, who, to judge by the laughter, are mostly children, but remains caught up in what he is doing. What exactly he was doing was much discussed. The circus became popular with other artists and with fashionable hostesses who got him to perform at their parties in Paris and New York. It was admired by Cocteau, compared with Chaplin as the essence of the tragi-comic art, and seen by the critic Legrand-Chabrier in 1927 as a masterpiece of ‘stylised silhouettes’. ‘This is not,’ he wrote, firmly pegging out the territory of ‘fine art’, ‘a mechanical toy.’

In Thomas Wolfe’s novel You Can’t Go Home Again, published posthumously in 1940, Calder appears, barely disguised, as Piggy Logan. Piggy is booked by a Manhattan socialite to perform at her party and duly turns up, a shambling figure with two bulging suitcases. Wolfe portrays him as an eccentric, a kind of holy fool who is taken up as a novelty by the vapid flapper culture of the interwar years and mistaken for an artist by a pretentious avant-garde. If Calder had never done anything else after the circus, that is perhaps how he would be remembered, as a naive or a curiosity, if he was remembered at all.

Parts of the circus, with extracts from the film, appear in the first galleries, accompanied by other figurative wire sculptures that Calder was making at the time. Some are suspended, some wall-mounted, all so obviously on the brink of movement that Tate has supplemented the usual instruction not to touch the exhibits with a request not to blow on them either. Close up the smaller figures reveal visual puns. A clothes peg makes a dachshund’s head as Picasso later made a bull’s head from a bicycle saddle. The larger figures are sometimes comic, like the jiggling outline of the burlesque dancer Josephine Baker, or the strong man with the tiny head and the outline comedy genitals that Calder gave many of his male nudes. They can also be sinister. A floating head of Medusa casts a nasty shadow. The head of Léger is a true portrait, the crown of his hat a single line that creates an impression of three dimensions from every side.

There is a sense of anticlimax when the exhibition arrives at 1930 and the moment when Calder entered the world of ‘fine art’. A visit to Piet Mondrian in his studio brought about a Damascene conversion to abstraction. After this the figures gave way to several years of uneven experiment. Calder had not lost his playfulness: he drily suggested to Mondrian that he might liven up his work by making his rectangles ‘oscillate’ a bit, an idea that was coldly received. But it took time to translate the artistic and mechanical ingenuity of the circus, the wit and surprise, into abstract sculpture. He tried motors, which broke down, and forms suspended against painted backgrounds, which glow agreeably but are best read from one viewpoint and to that extent are self-defeating. The most convincing works of the mid-1930s are those that recall another kind of non-art moving object, the orrery. In 1922, in a boat off Guatemala, Calder had seen ‘a fiery red sunrise on one side and the moon looking like a silver coin on the other’. He now began to bring orbiting discs and ellipses into his work. A Universe of 1934 is a motorised spiral sculpture that takes forty minutes to perform all its permutations. When it was exhibited Einstein watched the full routine, much to Calder’s gratification. Today it can no longer be run; it is the ghost of a machine, an embodiment of the problem that has dogged moving sculpture since the Middle Ages: the fact that mechanisms wear out.

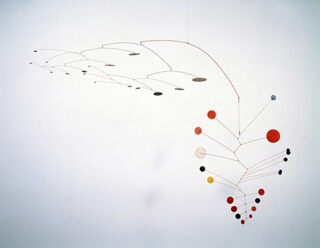

The exhibition picks up again with the eruption of the joyous yet poised compositions of balancing, echoing forms that are the mobiles. The spirit of the circus finds its way out in delicate abstracts made on a larger scale than any of the previous work. One of the biggest, in black wire and white discs, is Snow Flurry (1948). ‘Flurry’ is the perfect word which, unlike ‘shower’ or ‘fall’, catches the idea of continuous mid-air movement. It might be applied to all the mobiles. Snow Flurry is beautifully displayed in front of a window covered with a white blind, the grey light of a snowy day bathes it as it moves very slightly in a draught. Vertical Foliage (1941) with its black leaf shapes and Gamma (1947), whose bright red and yellow discs dance in the face of Mondrian’s static rectangles, are among the most spectacular of its companion pieces.

By the time they were made Calder was internationally recognised as an artist who had invented ‘a new conscious use of space’. He exhibited with Picasso and Miró at the 1937 Exposition in Paris, but he also went on performing the circus until his death in 1976. He didn’t think of it as a childish thing to be put away. Yet the ambivalence of Wolfe’s account still lingers in the world of ‘fine art’, which has tended to reach for words like ‘ludic’ and ‘performative’ where the early figurative work is concerned. Now it also feels the need to grapple with anxieties about ‘appropriateness’. In the book that accompanies the exhibition (but is not, frustratingly, a catalogue), Alex Taylor asks, apparently in all seriousness: ‘What are we to make’ of the ‘densely coiled spirals’ on the chest of Calder’s Josephine Baker? He worries about ‘crude stereotypes’ but reassures himself: the spirals ‘stand as a sign for motion itself’. They do of course but also for the fact that the naked human body in motion is as likely to be comic as erotic. The tennis champion Helen Wills, who troubles Taylor less, has a wire bow for breasts, which fly out centrifugally as she leans into a forehand; and when Calder’s nude male acrobats stand on their heads, the effect of gravity is fully accounted for in a satire on all the decorous bronze and marble penises of antiquity. He enjoyed what Taylor sternly calls ‘the lewd and the salacious’ as much as the beautiful and the delicate, the circus as much as the mobiles.

There used to be people who would only take abstract art seriously if the artist could, like Picasso, ‘draw properly’ when they wanted to. The obverse still obtains in art criticism. Because Calder became an abstractionist his clowns, strongmen and the bouncing kangaroo have been let into ‘fine art’, but as they hop in over the inverted commas they still get sidelong looks.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.