Frederick Swynnerton was a portrait painter born in Douglas, capital of the Isle of Man, in 1858. His father was a sculptor and stonemason: so were two of his four brothers, Joseph and Mark. Robert became a jeweller, while Charles was a churchman, who moved to India where he became a chaplain in Delhi as well as a folklorist. The stories contained in his book Romantic Tales from the Punjab, were, he said, of the ‘highest possible antiquity, being older than the Jatakas, older than the Mahabharata, older than history itself’.

Frederick never knew a single career. He wrote about neolithic Manx history, he wrote on Indian themes for the Journal of the Anthropological Institute of Great Britain, but painting was dominant. He was taught first in Rome, where he lived in the ménage kept by his older brother Joe and his wife, Annie Swynnerton, the painter, suffragette and the first woman to to be elected to the Royal Academy. He went on to the Académie Julian in Paris and then set out for India, hoping to make a career for himself as a portrait painter. (He never entirely got over his time in Rome. He revisited the city years later and acquired part of a mural from Nero’s Golden House, which depicts Leda waiting for her swan. He sold the fragment to the British Museum in 1908 – the portraitist of one empire collecting and selling the art of another.) He married the daughter of an Anglo-Italian fencing and soldiering family, and lived with them in Simla.

‘Portraiture is always independent of Art and has little or nothing to do with it,’ the painter Benjamin Haydon wrote in the 1820s. ‘It is one of the staple manufactures of the empire. Wherever the British settle, wherever they colonise, they carry and will ever carry on trial by jury, horse racing and portrait painting.’ Portraiture isn’t really independent of art, but as Caroline Corbeau-Parsons explains in the catalogue to the Artist and Empire exhibition at Tate Britain (until 10 April), portraiture in India wasn’t simply painting; it was part of a rite introduced by Warren Hastings to reduce corruption within the East India Company. Instead of accepting ornate gifts from Indian potentates, officials were to be given pictures of those they wished to influence or rule over.

So painters like Frederick had an imperial calling, just as religious men, like his brother Charles, had. Or at least an opportunity: the problem faced by portrait painters in India was that their sitters didn’t always pay since they got nothing in return. That presumably was the point: the unreciprocated act of giving was a blunt reminder of the power of those unto whom gifts are given, but the people most likely to lose out were the artists themselves. Frederick’s life in India wasn’t easy.

In her introduction to the catalogue, the curator Alison Smith says it’s ‘an anomaly that having laboriously assembled over the course of centuries the world’s largest empire, the British … should have been so reticent in making any great claim for their art. Indeed, compared to the antique remains of Rome, or the heroic history paintings epitomising la gloire of imperial France, the visual language of the British Empire was rarely grand or public.’ Pictures never expressed the idea of the imperial as forcefully as railways, harbours or cities, and the architecture associated with them – Lutyens’s Delhi is not modest. There are no ruins in London, but evidence of empire is everywhere; so much of the city is monument to it.

Was it that the British were reticent about making claims for their art, or that imperial art lost importance once the empire appeared to be on its way out? To be associated with it then smacked of being on the losing side, or out of date. There’s nothing like winning, or converting a loss into a heroic and magnificent defeat, which may be winning’s equal, or its better. It’s quite the achievement of the Artist and Empire show that it conveys what so many imperial pictures originally wished to convey: the dazzle of it all, the lording it, the flashiness, the hubris, the benevolence of the ruler, the last stand of the battalion, the heroic death of the general, the swagger of the governor of Malaya. Many of the pictures in the show have that quality of being recognisable even if you’ve never seen them before (but maybe you have, in illustrated history books from the 1960s and before). A man in Victorian military uniform with remarkably elegant trousers stands at the top of a flight of stairs leading to a ramshackle house; he has a pistol in his right hand but it looks as if he’s out of bullets; he appears to be nonchalantly checking the time on the watch on his left wrist, even if this is the hour, the minute and soon to be the second of his death. Men with spears and swords are climbing up the stairs towards him dressed in cheap white robes – angels they’re not, but despite their number they don’t appear entirely confident they’ll get their quarry. It’s not difficult to guess that this is General Gordon in Khartoum.

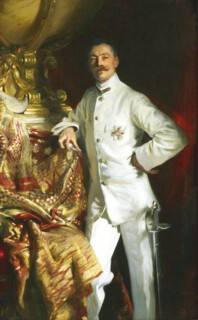

To be vain is a character flaw for those who aren’t, and there was nothing like empire to give vanity rocket-like lift. In Karsh’s photograph of John Buchan, who was governor of Canada in the 1930s, the wildly popular novelist wears a North American Indian war bonnet, his weathered face is in semi-profile, he’s wearing gloves, and he looks as if he could take on an army on his own. Sargent’s portrait of Sir Frank Swettenham, High Commissioner of the Malay Straits and Singapore, is a study in hauteur – the arrogance maximised by his white military tunic and the twirled and waxed moustache of a Parisian dandy of the Belle Epoque. That picture has quite a kick – offensiveness radiates from it. There’s the uncertain sexuality, too, though there’s nothing hesitant about Sargent’s treatment: Swettenham is pure British power and you might not like that, but he appears to tell you he really doesn’t care what you think.

Augustus John’s T.E. Lawrence is more unsure of himself, and the happiness of his expression suggests a man who liked to be liked. He’s wearing an Arabic head dress, and displayed next to John’s portrait of King Faisal – whose resemblance to Alec Guinness, the man who played him in Lawrence of Arabia, is uncanny. When the two pictures were first exhibited at the Alpine Club in 1920, Lawrence was a frequent visitor, as ‘enraptured by his own image’, John said, as he was with himself.

There’s nothing new about imperial vanities, any more than there is about the aristocrat as spiv or hippie – dressing-up has always been part of the courtly game. In 1635, Van Dyck portrayed the long-haired Earl of Denbigh – the first aristocrat to travel through India – in rose-red pyjamas threaded with gold stripes. He looks like the fat, middle-aged bassist of a 1970s rock group that against its better instinct has refused to disband. An Indian boy wearing an elaborate turban and a golden tunic looks up at his master – a trope endlessly repeated in British imperial portraiture – indicating with his index finger that he knows something that Denbigh should also know.

There are many red coats on the walls of this show, and no coat is more red than that of the just dead General Wolfe as portrayed by Benjamin West. Loyd Grossman’s Benjamin West and the Struggle to be Modern (Merrell, £35) explains the furore the picture created, and Joshua Reynolds’s attempt to suppress it. Depicting a mythic death in contemporary dress was out of order in 1770 (the version in the Tate is a later one, painted in 1779). West took no notice, the image was a sensation, copies were made, and engravings of the picture widely circulated. History painting was never the same again. The scene shows the complex sociability of the dead hero, whom life appears to have just left (his eyes are still open), surrounded by officers, while to the left is the befriended if pensive Indian, who sits and looks not at anything specific but at the scene. The war of independence, the only successful attempt to resist British colonial rule in the empire’s history, was far from over when West painted Wolfe a second time.

The visual depiction of the empire’s origins and subsequent expansion through maps and topographical devices is another of the show’s themes, along with the portrayal of the raiders and buccaneers who harried the empires of Spain and Portugal. So is the hoarding mania of men such as Joseph Banks, and the ways the ephemera and trophies of empire were taken up by artists in Britain. Not on show, but in the catalogue, is Philip Steer’s engrossing 1881 portrait of a bearded man who looks as old as the century. He’s reading a newspaper, you can’t make out the print, he’s expressionless. What of the War? is the picture’s title, and in its unstated, ambiguous way it conveys the numbness of a man who has read about imperial wars day-in-day-out for ever.

None of Frederick Swynnerton’s pictures is on display, which is no surprise since his art was uneven and much of it lost. In 1917, he went to Bombay to see his daughter Margery, who had been a nurse in Iraq where she caught pneumonia – she would become my grandmother. His idea of a get-well present was a bottle of champagne. She, like her father, was a painter and shared his belief in the therapeutic powers of fizz. ‘Tea? Coffee?’ she asked when I went to have breakfast with her after an overnight flight from the US. ‘Champagne?’

Fred died suddenly in Bombay in 1918 and was buried at the Sewri cemetery. He had been on his way from one empire to the ruins of another: he was bound for Rome.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.