Belt buckles are a big deal in the American South. There are buckles embossed with names, or birds, or playing cards; you can even get programmable LCD belt buckles that display whatever message you like. A sturdy buckle looks good even after a hard day’s work, so if you’re doing physical labour, it’s a handy way of catching someone’s eye. For rappers who wear their jeans low, a buckle has practical benefits too. In the 2000s, when the ‘Dirty South’ replaced New York as the heartland of hiphop, belt buckles were used for bragging and branding. Everyone wore them, Stephen Witt writes in How Music Got Free, at the CD pressing plant in North Carolina that handled heavyweight hiphop labels such as Def Jam, Interscope and Death Row. ‘The white guys wore big oval medallions with the stars and bars painted on. The black guys wore gilt-leaf plates embroidered with fake diamonds that spelled out the word “boss” … Even the women wore them.’

Dell Glover, a manual worker at the plant and a small-time video game and music pirate, had been trying to find out how CDs were smuggled off the production line, past the security guards and metal detectors, and out of the factory. He knew they were getting out somehow, because bootleg hiphop CDs were being sold on the streets of neighbouring towns. Eventually he realised how it was done. ‘Position your oversize belt buckle just in front of the disc; cross your fingers as you shuffle towards the turnstile; and if you get flagged, play it very cool when you set off the wand.’ Glover went on to leak many of the biggest albums of the decade, including Lil Wayne’s Tha Carter, 50 Cent’s Get Rich or Die Tryin’ and Kanye West’s The College Dropout, at a time which, in retrospect, looks like the mainstream music industry’s last hurrah. He was, in Witt’s estimation, ‘the most fearsome digital pirate of them all’.

In the 1990s, when he was in his twenties, Glover had spent his overtime payments from the factory on motorbikes, breeding dogs and buying firearms. But then the internet arrived ‘in Glover’s trailer from outer space’, thanks to one of the first commercially available satellite broadband connections. The lives of people in rural or suburban areas – Glover lived in Shelby, a small town 45 miles from Charlotte – were dramatically affected by the internet, whose potential to connect everyone, wherever they were, to everyone else, reconfigured the relationship between the centre and the periphery. Glover’s distribution network, suddenly, was potentially limitless. He began passing the digital audio files ripped from his smuggled CDs on to an internet pirate (or ‘warez’) group called Rabid Neurosis (RNS), via a contact in California he knew only as Kali. The music was stored on file servers that were accessible only to members of the group. The servers also carried movies, software and computer games, which Glover downloaded and sold on the street and in barbers’ shops. He became a major figure on the piracy underground, known to its adherents as the Scene.

The pirates that Kali recruited for RNS might be music directors at US college radio stations with access to new promo CDs or music journalists in the UK with insider connections to labels. But they also included the so-called Tuesday rippers, foot soldiers who bought CDs on the day of release in order to put them online. Most of them didn’t make money out of their hobby; on the contrary, most of them spent money and time sustaining it. Scene members even worked together to draw up an exhaustive document, more than five thousand words long, which set out how to leak mp3s, specifying quality thresholds, naming conventions and other community standards. For a while, the Scene acted as a kind of publicity front for the music industry: the albums that got leaked became the most hyped, and the biggest-selling.

RNS had leaks of its own, however, and many of the most sought-after albums of the late 1990s and early 2000s, having first been available only on RNS’s servers, began to appear on those of software clients such as Soulseek, LimeWire and Napster, often before their scheduled date of release. Napster was invented in 1999 – just after Universal took over PolyGram to become the biggest player in the US music business – by an 18-year-old college dropout called Shawn Fanning. He had been a lurker in internet chatrooms set up for the purpose of sharing music, so knew how to find as much pirated music as was out there, but he’d become frustrated at still not being able to find as much music as he wanted. Napster aimed to increase the amount of music available by connecting users to each other via a centralised server, so that people’s collections of music files could be shared directly, ‘peer to peer’. The software was freely available, and took off quickly; by 2000, Napster had nearly twenty million users. Because the peer-to-peer architecture connected users to one another’s music libraries, rather than to an unwieldy central stockpile of music, the download speeds were quicker and there was more choice – the more users, the more music there was to be had.

On 24 February 2000, Hilary Rosen of the Recording Industry Association of America convened a meeting of major record label bosses. She asked executives to name a song, any song, and her staff would find it on Napster. They even managed to find a track that hadn’t yet been released: ‘Bye Bye Bye’ by NSYNC. When shortly afterwards a demo of a song by the vastly successful rock band Metallica turned up on Napster, the industry finally roused itself to action. Conglomerates such as Universal spent much of the decade engaged in legal pursuit of bedroom file-sharers, many of whom were allowed to walk free by sympathetic juries. One of Witt’s main characters is Doug Morris, a music industry veteran who was head of Universal between 1995 and 2011, before taking over at Sony. Much of the book is about his battles with the ever adaptable digital pirates, and with the manufacturers of mp3 players. Apple’s introduction of the iPod in 2001 triggered a huge increase in the amount of leaked and pirated music available online: people began searching the web for music to put on their devices, and the underground increased its efforts to meet the demand.

By 2001, peer-to-peer networks had been blighted by the accumulation of shoddy files: Napster, Limewire and Gnutella were full of poor quality, often wrongly titled mp3s. A 25-year-old New Yorker called Bram Cohen, a programmer at a short-lived internet start-up, saw an elegant way to improve the system. Each file to be distributed could be split into bits of information, Witt explains, then ‘instead of downloading the entire [song] from one user, you could download one one-hundredth of it from a hundred users at the same time … A file transfer like that could happen quickly, perhaps even instantaneously.’ Users would download a ‘torrent’ file, which contained information about the music files they wanted (name, file size etc) as well as a list of ‘trackers’ – web servers that connect peers with each other. Once the user opened the torrent, it would seek out the trackers and automate the rest of the downloading process. Cohen launched BitTorrent in July 2001. At first trackers were thin on the ground, but as with the mp3, pirates soon grasped the potential of the new technology. In 2003 a Swedish website, the Pirate Bay, began hosting trackers for movies, music, software, pornography and anything else you could digitise. Its founders saw piracy as an act of civil disobedience. ‘US law does not apply here,’ one of them, Gottfrid Svartholm Warg, wrote to DreamWorks SGC when they demanded that trackers for their film Shrek 2 be removed from the site.

Other torrent sites kept a lower profile. Alan Ellis, a 21-year-old computer science graduate, created Oink’s Pink Palace in order to improve his web scripting and database administration skills (or so he would claim later in court). Oink was an invitation-only site which hosted torrent trackers. It required users to disclose their email and IP addresses, and to upload new material to the site regularly. In exchange, it hosted only audio files of the best quality: mp3s had to be ripped from original CDs and tagged according to rigorous standards. Unlike the Pirate Bay, Oink encouraged its users to be sociable and its forums became meeting places for clued-up music fans. Invitations to Oink were sought after, and because the site’s rules were so stringent, new users added ever more obscure music to its impressive catalogue. By 2006, the site had a hundred thousand users and hosted torrent trackers for nearly a million albums – four times more, Witt points out, than the iTunes store had at the time.

In January 2007, suspecting that law enforcement agencies were on their trail, Glover and Kali announced RNS’s final release. But Glover couldn’t quit. By April, he was leaking music from the plant again. When the FBI finally caught up with him later that year, he pleaded guilty to the charge of conspiracy to commit copyright infringement. He had no way of identifying Adil Cassim – a twenty-something IT administrator who lived with his mum, and whom the authorities alleged was Kali – in the courtroom, as he had never met him in the flesh. Cassim got off; Glover spent three months in prison. After his release he became a professional computer repairman.

Music piracy only became possible thanks to advances in audio compression technology. A CD stores 74 minutes or so of music: a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth, according to industry lore. That’s about 700 MB of data. A standard modem in the late 1990s, carrying 56,000 bits of digital data per second, would take around 24 hours to download the five billion bits encoded on one CD. Getting a copy of an album via the internet was an absurd chore. If you wanted to steal music, you were better off going round to your friend’s house with a cassette recorder. That changed with the invention of the mp3 format in the early 1990s by Karlheinz Brandenburg and his colleagues at the Fraunhofer Society, a German state-funded research organisation. They had set themselves the goal of shrinking audio data files by a ratio of around 12 to 1. The eventual outcome, they hoped, would be a networked digital music jukebox service.

Psycho-acoustics had shown that audio recordings were ‘a maximalist repository of irrelevant information, most of which was ignored by the human ear’, Jonathan Sterne writes in Mp3: The Meaning of a Format (2012). In other words, audio recordings could have data stripped from them and still sound as good. The information theorist David Huffman had also demonstrated that sonic regularities – a violin string vibrating at a steady pitch, say – could be encoded in such a way that they took up minimal data, then subsequently decoded and expanded into audio information at playback. On the basis of these insights, and after many long nights in the laboratory listening to encoded versions of Suzanne Vega’s intimate a cappella song ‘Tom’s Diner’ on thousand-dollar headphones, the Fraunhofer team hit on a compression format that sounded, to their ears, indistinguishable from the original audio. But it wasn’t until the pirates got hold of it that the technology became popular. In February 1995, the Fraunhofer group struggled to get anyone to listen to their prototype mp3 player at a trade show in Paris. In September the following year, a music pirate using the name NetFraCk gave an interview in a Scene newsletter in which he said that the mp3 was their secret weapon.

About a year ago I met Andy, who runs a download blog for classic and rare jazz. In the eyes of the music industry he’s a pirate, but he does it purely for kicks. He is young, technologically sharp, and has spent his late teens working behind the counter at a coffee shop. In his own time, he uses his knowledge of peer-to-peer networks, obscure music blogs and defunct filesharing sites to put up classic albums – dozens a day – for people to download. If he doesn’t have it already, he can probably get it for you. He makes available, for free, many albums that aren’t issued by the entertainment conglomerates that own them, and his website is a more elegant and illuminating repository of jazz than any record store. Andy sees himself as a librarian rather than a criminal, a preserver of an artform that has been largely abandoned by big business. At the end of our chat I suggested catching a jazz gig in London sometime and he seemed taken aback. Live music wasn’t on his agenda. He preferred to stay at home and nurture his ecosystem.

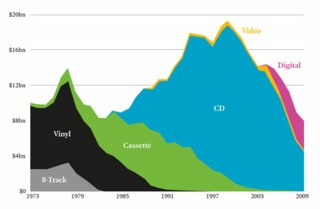

Pirates like Andy have succeeded, in many ways, in freeing music. It has been freed, for instance, from the CD, which has fallen out of favour with consumers in the last few years. The CD’s promise of ‘perfect sound for ever’, as early Philips ads for the format put it, turned out to be wishful thinking. The discs picked up scratches over the years, and as a tool for storage the CD was trumped by the iPod and iTunes, which can hold, and keep a back-up copy of, an entire music library. The mp3 is highly portable and, for teenagers not least, the ability to carry music around has always been more important than audio quality – hence the success of music playback machines, from the transistor radios of the 1960s to the boomboxes of the 1980s and the petite iPod docks and speakers of the 2000s. Mp3s have changed the way our homes look: the space-age bachelor pads of the 1960s, 1970s and 1980s featured large, stereo hi-fi systems, but the dream home of the 21st century is a minimal living space in which the technology is so discreet as to be almost invisible.

Music has also become free from the parameters of the album format, which could always be seen as a case of ‘product bundling’, obliging consumers to pay for tracks they didn’t actually want. Such freedoms, as Witt says, have meant that fewer and fewer people are willing to pay for music any more. As soon as the album bundle fell apart, the average amount spent on recorded music per consumer began to fall. (Live music, on the other hand, has had a renaissance.)

The graph above shows how the music industry’s income has been propped up across the decades by the successive introduction of different formats. Industry revenues today are nothing like what they were in the late 1990s, the golden age of the CD, but they have been bumped up recently by the emergence of legal digital downloads and streaming. The rapid evolution of Spotify has had a particularly significant impact on how contemporary music is consumed and distributed. In a way, it is the digital jukebox Brandenburg dreamed of. Since its launch in Scandinavia, France, Spain and the UK in 2008, it has offered free, high-quality desktop audio streaming of music from most of the major record labels, with just the occasional advertisement to pay its way. Spotify’s launch in the US was delayed because the company failed to strike licensing deals with American record labels, which were concerned that it would damage their already fragile sales. But Spotify managed to win them round – or grind them down – with one-off payments to labels and publishers, injections of funding from tech conglomerates abroad, and evidence that users were willing to pay for premium, ad-free accounts. Its most persuasive argument was that Spotify, by making so much music available so cheaply, might actually discourage petty piracy. Given that nothing had managed to stem the flow of pirated music since Napster became popular, it’s understandable that music labels gave it a shot. But whether or not it has discouraged piracy, Spotify has also put limits on the amount of money recorded music can make. It pays microscopic fractions of pennies to artists and labels, who face a difficult choice about whether or not their recordings can be streamed: either they’re available through Spotify or they’re not, in which case far fewer people will listen to them. ‘Streaming,’ Witt writes, ‘didn’t solve everything. It may not have solved anything.’ Tech companies like Spotify, Apple, Google and Amazon are the new major labels.

There is no scarcity in the digital world, and if a product isn’t scarce, it is very hard to persuade people that it has monetary value. Record labels can be forgiven for demanding greater control and regulation of the digital file distribution. On the other side of the argument, bodies such as the Pirate Bay argue that copyright has become little more than a tool for ringfencing capital, and that ‘rights holders wanted – actually needed – to turn the internet into a police state.’ It’s certainly true that while copyright purports to protect innovation, many of the major technological and aesthetic innovations in the last twenty years have come from people playing fast and loose with copyright. There are some who hope the era of recorded music will turn out to have been a historical anomaly. Before recording devices were invented, music was preserved by oral traditions, contained in scores or listened to in real time; perhaps music could become something like a folk form again, with musicians liberated from financial obligation and listeners from ownership, allowing music to be part of a common cultural fabric. In an abrupt coda, Witt realises that his personal archive is ‘just an agglomeration of slowly demagnetising junk’; he goes to a data destruction company to get nails fired into his hard drives, ridding himself of tens of thousands of mp3s. The ones and zeros that make up the digital music revolution are hard to preserve, but also hard to kill and, as the music industry has discovered to its cost, hard to contain.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.