How close can you get? That seems to be the question Lee Miller’s war photographs are trying to answer. In theory, it’s the question behind any action shot, or any embedded reporting, but in Miller’s case it was especially wilful. The only cameras she took with her when she joined the 83rd infantry division of the US army, as it advanced across Europe in 1944, were Rolleiflexes. Contemporaries such as Robert Capa would have found that decision insane – almost as insane as joining the advance in the first place, given that Miller was a former fashion model who never wore the same outfit for more than a few hours. She was also a hypochondriac. Her colleague David Scherman (who took the famous picture of Miller in Hitler’s bathtub) later remembered that ‘you named a disease and Lee would imagine she had it in no time at all.’

A Rolleiflex might seem exactly the wrong camera to take to a warzone. It’s cumbersome (especially if you carry two, as Miller did), you have to load new film every 12 frames and you can’t change the lens. But a Rolleiflex forces you to get to the heart of things. Your only options are to get close, or even closer. In taking her Rollei into battle, Miller wasn’t blithely importing the equipment of artists and amateurs; she was asserting that there was something qualitatively different to be shown in a war.

Lee Miller: A Woman’s War (until 24 April) reveals this more clearly than any earlier grouping of her photographs. The exhibition has been rigorously conceived by Hilary Roberts, who has done excellent work in the past on the photographic history of World War One, and on the war work of Miller’s nemesis Cecil Beaton. Roberts has assembled a collection to prove her contention that most of Miller’s subjects were women, and in doing so has admirably avoided the obvious. She doesn’t include the pictures of troops directing mortar fire or badly mangled sergeants which were reproduced in a volume called Lee Miller’s War ten years ago. Though Miller was among the first to enter Dachau at its liberation, her pictures of corpse-filled train cars, famously published in British Vogue under the heading ‘Believe It’, aren’t here. Nor is the one of the SS guard who hanged himself at Buchenwald. Instead, we see prisoners forced to become camp prostitutes, and a prisoner turned camp nurse. Earlier, Miller had documented the work of the Wrens in Britain and nurses in field hospitals in France. Now, she photographed the other side.

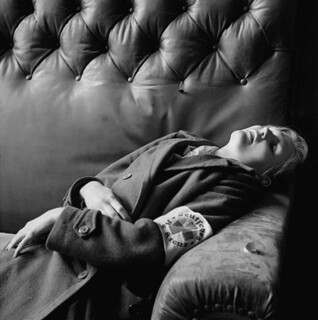

The image included here of Regina Lisso, the recently dead daughter of a Nazi deputy mayor, is one of many taken at the scene of the family suicides at the Neues Rathaus in Leipzig. In this version, Miller gave the girl a complicated and upsettingly lyrical aspect: the pose of a tragic beauty, a hint of evil and childlike teeth. Then there are the collaborators. Capa’s well-known picture of a shaven-headed tondue showed her being marched through the streets with her baby; Miller chose a private moment before that public shame. The caption beneath her portrait of a female collaborator in Rennes tells us that Miller’s subject was being interrogated. But we see her so close up it’s as if the interrogator isn’t there – the shorn collaborator is right next to us, gazing at the ground in either pain or penance.

Man Ray got some of his most beautiful images out of the ecstatic blur of Miller’s arched neck, her face in solarised profile, and the constructivist play of shadows on her torso. But Miller’s contribution to that world as a photographer was weak. Her art mimicked Man Ray’s to dreary effect; her fashion shots were stiff, predictable and loveless. On the strength of these efforts alone, it’s hard to imagine why she wanted to become a photographer. Was she just tired of being looked at? The Imperial War Museum exhibition suggests, with its inclusion of her father’s near pornographic portraits of her and the reminder that she was raped by a family friend at the age of seven, that she had every reason to turn the tables. Yet it took her a decade to know what she wanted to see. In theory, she threw off the shackles of modelling in 1930; in practice, she remained restricted by beauty – the industry, and perhaps her own – until the ugliness of the world became undeniable.

In the Second World War Miller met her subject, the way fighters are said to meet their match. Her photographs were not just different, they were better. Her compositions, which you’d think would be easier to formulate when sitters were still, were more inventive on the hoof. Her American army nurses in Oxfordshire were more beautiful than any of her models; her nurse at the end of a long shift during the Battle of St Lô had a graphic quality Paul Strand would have envied; her parachute packer at HMS Heron had the kind of élan that Richard Avedon would strive for a decade later in his fashion spreads.

She covered the home front for Vogue, and then, though she had lived in London for many years, her American passport allowed her to become one of only four female photojournalists accredited to the US armed forces. With the exception of Margaret Bourke-White, the most experienced of them, they all took on male-sounding names: Toni Frissell, Dickey Chappell, Lee Miller. Officials found it hard to deal with free-roving correspondents of either sex; women weren’t even allowed to enter combat zones. Despite this, Miller became what Scherman called ‘a proper GI’, defying the terms of her accreditation and being put under house arrest as a result.

Accounts of her soldier-like swagger – some of them her own (‘I grabbed a pocketful of flash bulbs and film and clambered into a command car’) – obscure the fact that Miller developed a distinctly intimate form of reportage. She photographed the war the way she photographed her friends: Leonor Fini, volunteers in a camouflage workshop; Nusch Eluard, anaesthetists in Normandy; Anita Loos, firewomen in Woking; Dora Maar, Wrens relaxing in the sun. Bourke-White once confessed she’d felt relieved that she could put the camera between herself and the horrors at Buchenwald. The terms of Miller’s engagement were more personal. During the Blitz, she had written to her parents that a lull in the bombing had given her ‘a chance to catch up on being human’. That’s the effect her war photographs have. She was always up close, looking, as if at any time one of her subjects might turn out to be someone she loved.

‘Where do they go from here?’ Vogue’s editor asked rhetorically, about women after the war. ‘How long before a grateful nation forgets what women accomplished when the country needed them?’ Miller was at a loss when the war ended, convinced that the result was ‘not what anyone fought for’ and that she had, in her own words, ‘braved flesh and eyesight’ for little. She was dogged by depression and alcoholism until her death in 1977. In 1947 she had a son, Antony Penrose, who has curated her posthumous career with grace, and has spent much of his life trying to find out who his mother was, before he knew her.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.