The modern Conservative Party is never happier than when Labour has a unilateral disarmer as its leader. In 1986 Margaret Thatcher arrived at her party’s annual conference in Bournemouth with a spring in her step, despite having endured months of bruising political infighting in the aftermath of the Westland affair. She promptly fell over a manhole cover and sprained her ankle but even this did little to dampen her spirits. The reason for her good mood was that over the previous two weeks both the Liberal and Labour Party Conferences had voted in favour of unilateral nuclear disarmament. In the case of the Liberals this merely confirmed Thatcher’s view that they were not to be taken seriously, particularly as the vote set the members at odds with the leadership of the Alliance and represented a direct rebuke of David Owen’s much more hawkish SDP. Labour was different. ‘The Labour Party will never die’ was one of Thatcher’s mantras. What Labour did mattered because it was the only alternative party of government. And in this case the party members were in tune with the leadership: Neil Kinnock, who had spent the past few years painstakingly trying to distance himself from the militant elements of his movement, was nonetheless unwilling or unable to give up his personal commitment to unilateralism (he later said that even if he had wanted to, his wife, Glenys, would never have allowed it; the party might have survived but his marriage wouldn’t have).

Thatcher pounced. She used her conference speech to excoriate Kinnock for his pusillanimity. A future Labour government had waved the white flag before it had even arrived in office: ‘Exposed to the threat of nuclear blackmail,’ she told the conference, ‘there would be no option but surrender.’ She contrasted the weakness of Kinnock’s position with that of more robust Labour politicians of an earlier generation – Gaitskell, Bevan – who had defied their party’s wishful thinking on matters of national defence. They had been patriots. Kinnock, by implication, was not. The Tory high command no longer needed to come up with a fresh campaign blueprint for the election it hoped to call the following year. It had this one on standby, just waiting for the occasion.

By chance the party conference in Bournemouth took place a few days before the Reykjavik summit between Reagan and Gorbachev, convened to discuss ways of limiting their respective nuclear arsenals. Thatcher used the promise of this event to drive her message home. Reagan, she insisted, could negotiate because he started from a position of strength. Kinnock’s strategy would toss all that away, or at least Britain’s chance of playing any meaningful role in the discussions. ‘Does anyone imagine that Mr Gorbachev would be prepared to talk at all if the West had already disarmed?’ she asked her audience, entirely confident of the answer.

But in the event something unexpected happened. Though she liked Reagan and was readily charmed by him, Thatcher had always been a little suspicious of his occasional flights of idealistic fancy, particularly when it came to nuclear weapons. Luckily, as she saw it, the more hard-headed Gorbachev would be on the other side of the table. And the president was surrounded by seasoned advisers who would be sure to keep his feet on the ground. So Thatcher was horrified when she discovered what actually transpired in Iceland. Following hours of increasingly testy discussion about trade-offs between different categories of weapon, Reagan said in frustration that none of this would matter ‘if we eliminated all nuclear weapons’. Immediately, Gorbachev replied: ‘We can do that. We can eliminate them.’ Reagan’s secretary of state, George Shultz, sitting in on the conversation, couldn’t hold his tongue. ‘Let’s do it,’ he said. The implications of this sudden meeting of minds were, as one observer put it, ‘cosmic’. Within a matter of moments, the future prospects of the human race had changed. And so had Thatcher’s prospects of squashing Kinnock at the next election.

When they heard the news from Reykjavik, Thatcher’s inner circle quickly went into damage limitation mode. Their great fear was that Labour’s agenda would suddenly sound as though it were in line with the unfolding logic of superpower politics and the Tories would be the ones out on a limb. In particular, how would the government sell the expensive Trident nuclear submarine programme, the cornerstone of its defence policy, to the British people if the Americans were talking about doing away with nuclear weapons altogether? Thatcher therefore decided to present any progress on disarmament achieved at Reykjavik as a product of Reagan’s hawkishness rather than his peacenik instincts. She argued that Gorbachev had blinked first because of Reagan’s insistence that the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI or ‘Star Wars’) wasn’t up for negotiation.

This was somewhat hypocritical. Thatcher had long been suspicious of Reagan’s attachment to SDI because she thought it diluted the focus on the only sort of deterrence that really mattered: having greater firepower than the enemy. She treated it as one of Ronnie’s foibles. Now, though, she clung fiercely to SDI as the sole surviving stick with which the Americans could beat the Russians into submission. With hindsight, that is the way many Cold Warriors came to see it: SDI allowed Reagan to outspend and thereby outmuscle the Soviets. But Thatcher’s conversion to its merits was evidence of panic. She had to find something that left Kinnock on the wrong side of the argument and she was no longer in a position to be picky.

At the same time, she was determined to exploit her close relationship with Reagan to bring him back into line. That was something Kinnock could never hope to match: she had more clout in the White House than any other world leader, never mind a leader of the opposition. (This advantage was to be rammed home the following year when Kinnock paid a trip to Washington and Reagan’s team humiliated him – allocating him just 25 minutes of the president’s time and then ending the meeting five minutes early – to keep Maggie sweet.) Thatcher secured an invitation to Camp David, where she intended to remind Reagan of some hard political truths. Her principal aide, Charles Powell, drafted a memo in which he laid bare the core of the argument she would need to get across to the president (the emphasis comes from Thatcher’s annotations of the text):

You will cause me very real political difficulties if you pursue your proposal for eliminating ballistic missiles too actively. In our people’s mind it will raise two questions: isn’t Labour right after all in wanting to get rid of nuclear weapons … ? And why on earth should we pay out all that money for Trident, if it’s going to be abolished in 10 years? The next British general election could ‘turn’ on these points, so you must help me deal with these arguments.

In sum: worrying about the future of humanity is all very well, but what about the Labour Party?

This episode gives an insight into Thatcher’s remarkable strengths and weaknesses as a politician. Her mission at Camp David was a success, in her own eyes at least: she managed to get agreement to a joint Anglo-American statement that reaffirmed the necessity for ‘effective nuclear deterrents based upon a mix of systems’. Though nothing was said explicitly it was enough to convince her that Trident was safe. Cosmic disarmament was back in its box. She was helped by the fact that just before she arrived the story broke in a Lebanese newspaper that the Reagan administration had been secretly engaged in selling weapons to Iran in exchange for the release of hostages: the beginnings of the Iran-Contra scandal. This brought Reagan back to earth with a bump and forced a hurried denial (which Thatcher knew was untrue, given the briefing she had had from GCHQ about what the Americans were really up to). Reagan found himself in no position to withstand Thatcher’s potent mix of moral certainty and brazen flattery. She offered him her unflinching support over his domestic difficulties, on the basis that ‘anything which weakens you weakens America, and anything that weakens America weakens the whole free world.’ At the same time she reminded the president and his advisers that without a continuing nuclear shield American protection of Western Europe would be worthless. The fantastical ideas coming out of Reykjavik, she told Shultz in a private meeting, would ‘cause you to lose me and the British nation’.

Thatcher had an extraordinary ability to reconcile her deepest convictions with her practical political interests. She genuinely believed that nuclear weapons were a force for good and the sole guarantor of the peace that had lasted in Europe since 1945. She also knew that these beliefs put her in an excellent position to exploit Labour’s weaknesses on defence, so long as nothing happened to disturb the assumptions on which they rested. She was profoundly incurious about the reasons those assumptions should be coming under threat. She didn’t want to think about what had moved Reagan and Gorbachev to make their leap in the dark. She just wanted them back in their traditional roles. She had no desire to live in a world where her personal principles and her private interests were at odds with each other. She was a conservative.

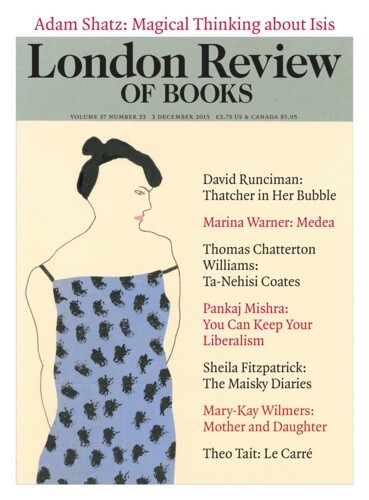

Charles Moore’s recounting of this episode reveals the strengths and weaknesses of his biography as it arrives at the apogee of Thatcher’s power. He is excellent on the high politics and the potency of personal connections. Powell, who provides the source for some of the most intimate material, is in many ways the presiding spirit hovering over this volume: the mischievous but utterly loyal courtier, who seems to relish deploying his formidable intelligence on causes he need never think through for himself. He luxuriates in the tight confines of his mistress’s imagination. He can gossip, he can settle scores, he can compose waspish character sketches, he can rearrange the pieces of the puzzle to his heart’s delight. What he doesn’t have to do is worry about why they are solving the puzzle in the first place. Thatcher’s own lack of curiosity about the forces at work in the society that she seeks to govern permeates this book. The result is that much of the history recounted here is airless, trapped inside the Downing Street bubble.

This is especially true of the struggle that Moore says resulted in ‘the most important single victory of her career’. The miners’ strike of 1984-5 is portrayed as a do or die contest between the government and those who sought to bring it down. The template is the Falklands War, in which Thatcher’s nerve was tested and her resolve held. Moore writes:

As in a war, the picture could change dramatically each day, and on several fronts. A ‘Daily Coal Report’ was supplied to ministers and officials, listing statistics of tonnes produced, pits operating and miners working, injuries to police, legal actions proposed and so on. Downing Street staff studied these details with almost as much anxiety and attention as they had devoted to the Falklands conflict. Instead of names like Bluff Cove, Goose Green and Mount Longdon, they became familiar with pits like Shirebrook, Manton and Bilston Glen.

All good boy’s own stuff. Thatcher herself was clearly not averse to this sort of thing: her special adviser David Hart sent her a typically vainglorious note as the dispute was stumbling to its close, parts of which she underlined: ‘We are on the brink of a great victory. If we don’t throw it away at the last moment. Much greater than the Falklands because the enemy within is so much harder to conquer.’ But unlike Moore’s description of the Falklands conflict at the end of Vol. I, which managed to convey the great drama of a high-intensity contest, something is missing here: a sense of perspective. What was the miners’ strike about? What was really at stake? Moore takes for granted that we don’t need to spend too much time thinking about these questions.

Part of the problem is that the Falklands analogy doesn’t hold. In that contest the Thatcher government faced its enemy square on: no one could be in any doubt about who was fighting whom. But during the miners’ strike the government was torn between its instinct to take sides and its wish to present itself as above the fray. ‘This is not a dispute between miners and government,’ Thatcher announced when the picketing of working collieries began. ‘This is a dispute between miners and miners.’ All Thatcher’s sympathies were engaged by the miners who, in the absence of a strike ballot, wished to carry on working. She was aware that she couldn’t take the fight directly to the NUM, for fear of alienating more moderate trade unionists. At the same time, despite her severe misgivings about the battle-readiness of the National Coal Board and the flakiness of its imported chief, Ian MacGregor, she resisted the impulse to take charge. She allowed herself to be persuaded by her cabinet secretary, Robin Butler, that it was too dangerous for the prime minister’s office to appear to be setting the terms of the dispute. She remained reliant on her energy secretary, Peter Walker, whom she didn’t trust and feared would do ‘a fudge, like Pym and the Foreign Office in the Falklands had tried to do’. But unlike Pym, Walker kept his job, because she didn’t dare sack him. In some respects her role in the miners’ strike more closely resembled Reagan’s in the Falklands War than her own: the deeply partisan but constrained overlord, forced to sit on his hands while others fight it out.

Moore would say the obvious difference was that Reagan’s fate didn’t hang on the outcome of the Falklands conflict whereas Thatcher’s was entirely tied to the result of the miners’ strike. Lose and she lost everything. But is that true? Certainly that’s the way she saw it: anything other than a decisive victory over the NUM would have seemed to her an intolerable compromise, forcing her principles to co-exist with an extremely uncomfortable political reality. But her perspective is not necessarily paramount. The strike was a complex interplay of conflicting forces and interests. If nothing else, her government’s relative insulation from some of the key decisions might have provided her with protection if things had gone wrong. Moore insists that the contest was on a permanent knife-edge, with ruin never far away:

At any moment, it was possible that trade union solidarity, or the effect of NUM violence, or legal disaster, or the mishandling of negotiations by the Coal Board, or a loss of political nerve would produce defeat. Even a national ballot [by the NUM], which Scargill refused and for which Mrs Thatcher repeatedly called, was full of risk for the government. Suppose the vote took place, and went the ‘wrong’ way …

Well, what then? The government would no doubt have been forced to compromise, with unpredictable results. Would the government have fallen? It seems very unlikely (Thatcher at this point had one of the largest parliamentary majorities in modern political history). The Labour Party would have faced its own difficulties if Scargill had been able to claim the high ground. It would all have been very messy. Sorting out the mess might still have been within Thatcher’s compass as a politician – there were many ways the fight could have continued – but it doesn’t seem within Moore’s compass as a historian. He ends his account by quoting Thatcher’s private secretary Tim Flesher: ‘No other British prime minister would have won the Falklands War or the miners’ strike. She showed unique resolution and clarity. She was terrifically inspiring. If she hadn’t won, we’d be like Greece.’ This is partisan bluster. If she hadn’t won, who knows what would have happened? But it wouldn’t have been that.

Moore’s account works best when the bubble is the story. The most dramatic chapter by far is the one that describes how the Thatcher government managed to tie its fate to the poll tax, a misjudgment of mind-bending proportions. Like all the best whodunnits, it is a slow burner. A group of clever young men – Oliver Letwin, John Redwood, William Waldegrave, among others – gather in various restaurants and country house hotels to bat around ideas for reforming the financing of local governance, encouraged and provoked by their mentor, Lord Rothschild. They were much clearer about what they wanted to escape than what they were trying to achieve. The government was desperate to find an alternative to the rates, which were deeply unpopular with homeowners, who were burdened with a disproportionate amount of the rising costs of local government. These people were for the most part Conservative voters – ‘our people’, as Thatcher called them – and they were increasingly angry about being stuck with the bill. The danger was especially acute in Scotland, where a rates revaluation was threatening increases of as much as 170 per cent, with potentially catastrophic consequences for Tory electoral prospects north of the border. So the young men were given licence to think big.

Eventually a radical idea began to take hold: why not tax individual residents as a means of making local authorities accountable to the people who use their services? That way profligate councils could be held in check by those paying for their wastefulness. It isn’t clear whose brainwave this was, though Waldegrave is the one who took the credit. The group was given a chance to present its scheme to the prime minister at Chequers on Sunday, 31 March 1985. Waldegrave told the assembled company that the average cost per head of the poll tax was estimated at £50, which would save many ratepayers a small fortune. Those on low incomes would be offered rebates, ‘but not such as to insulate them from increases in the community charge’ – as they hoped the poll tax would be known – ‘by high-spending councils’. Waldegrave ended his presentation with a flourish: ‘So, Prime Minister, you will have succeeded in abolishing the rates.’ Thatcher is said to have ‘purred’.

If this sounded too good to be true, that’s because it was. A Cabinet Office brief just six weeks later estimated that the poll tax would work out at an average of £160 per year. Even this turned out to be a vast underestimate: when the first bills finally arrived five years down the line, some taxpayers were being asked to stump up more than £750, and the average per person across the country was £363. The basic flaw with the scheme was that it required high bills in order to work: the aim was to show people how profligate Labour councils were being with their money, which meant they had to feel it in their pockets. The poll tax proved popular only in penny-pinching Tory councils like Westminster and Wandsworth, where it wasn’t needed. The notion of trying to win political popularity by introducing an inherently unpopular tax seems obviously daft, but years later, according to Moore, Letwin was still arguing: ‘That was the idea!’ The other big problem was that its unpopularity would make it very difficult to collect. Taxes on property have the advantage that houses are hard to hide; people, on the other hand, can easily disappear, especially from the electoral register. So a tax that could only do its work by driving people to refuse to pay it became the Tories’ idea of their secret weapon.

It isn’t as if the stupidity of the scheme is visible only in hindsight. Many saw what was wrong with it at the time. They included the most powerful man in the government, the chancellor, Nigel Lawson, who was one of the few people able to stand up to Thatcher if he chose. Lawson attached a personal memo to the one supplied by the Cabinet Office in May 1985, in which he said that ‘the proposal for a poll tax would be completely unworkable and politically catastrophic.’ But he did nothing to follow up on this warning and the plan was allowed to continue on its merry way. Lawson had decided that Thatcher was fixated on the subject and didn’t want to waste his breath, with other fights looming. When the cabinet approved the green paper that launched the community charge on 9 January 1986, there was considerable disquiet around the table. Peter Walker, still energy secretary, warned of the consequences: ‘The disadvantaged will howl; the advantaged will keep quiet.’ He added that if the chancellor was ‘thinking of a new tax, he wouldn’t think of a poll tax, for sound reasons.’

This was Lawson’s cue to weigh in, but he kept silent. Most people in the room were shellshocked, but not by the thought of the poll tax. It happened to be the same cabinet meeting which Michael Heseltine had stormed out of, to tell the waiting press that he was resigning from the government over the Westland issue. That was the big story, for politicians and journalists alike. The poll tax became an afterthought. The press didn’t pursue it because it already had its story. Labour didn’t make an issue out of it because the party didn’t want to be seen to be defending ‘loony left’ local authorities like the one in Liverpool. The architects of the scheme were able to press ahead, wishful thinking safely intact. Just how wishful the thinking had become was clear by the time of the 1987 general election. Thatcher went to Edinburgh during the last week of the campaign. After a torrid week of Labour attacks, she was looking for a strong positive message. ‘We pledged ourselves to abolish domestic rates and we have done so,’ she told a rally of Tory supporters, to loud applause. ‘And I am proud that we will first be introducing the community charge here in Scotland.’ So goes the Union.

It’s instructive to compare the account Moore gives of this fiasco to the one provided by Anthony King and Ivor Crewe in The Blunders of Our Governments, their litany of the cock-ups of the modern British state. Even in this exalted company – the Millennium Dome, the ERM disaster – the poll tax takes pride of place, ‘the blunder to end all blunders’ as they call it. King and Crewe are better than Moore at dissecting the institutional and policy failures lying in the background. They point out, for instance, that the £50 figure cited at that fateful Chequers meeting was predicated on the assumption that the poll tax would run alongside a modified version of the rates to help bed it in.

Moore never mentions this, so fails to explain how such a ridiculously low figure was arrived at. But if the number wasn’t as stupid as it sounds, Waldegrave’s final boast that the rates were being abolished was even more reckless than it appears, because he was promising Thatcher something he couldn’t deliver. Then, having promised it, he found he was expected to deliver it. King and Crewe show that much more attention was paid to the taxes the clever young men were determined to avoid than the one they were going to levy. They wanted to please their leader. All the familiar ways of raising tax revenue – income taxes, property taxes, sales taxes – were non-starters because Thatcher believed there were more than enough of those already. The appeal of a poll tax was that no government had tried to impose one for nearly three hundred years. That ought to have been a clue. But once they had rejected everything that was unpalatable, whatever remained, however improbable, had to be the answer. No one was willing to test the assumptions against the evidence. The Scots came to believe that they had been used as guinea pigs for the poll tax in a heartless experiment conducted on an entire nation. But even this is not true: had it really been an experiment, the government would have abandoned it as soon as it became clear how nearly impossible it was to implement. The fact that the poll tax came into force in England and Wales even after what had happened in Scotland shows that the institutional checks and balances of the British state had broken down.

What Moore gives us, by contrast, is the personality politics. He addresses the key high political question: if Lawson could see how badly this would end, why did he do nothing to stop it? The answer is that Lawson didn’t have enough skin in the game. Politics at this level is primarily about turf warfare. Local taxes were the one form of public revenue that fell outside the remit of the Treasury. Since no one was trying to invade Lawson’s personal territory he let them get on with it. Indeed, his main way of expressing his displeasure was to instruct Treasury officials that they shouldn’t contribute to the discussions about how the tax might work. It was, to his mind, nothing to do with them. As Moore says, ‘On the whole he did not much mind colleagues making fools of themselves … His main task, as he saw it, was to carve out and protect his own sphere of operations, so he almost washed his hands of the whole subject.’ This changed only once the tax was in operation and in deep trouble: in the summer of 1990 Chris Patten, the new secretary of state for the environment, dismayed at the mess he had inherited, appealed directly to the prime minister over the head of her chancellor for Treasury funds to soften the political impact. Now Lawson exploded, furious at the temerity of a new minister trying to muscle in on Treasury turf to bail out a tax that should never have been enacted in the first place. Lawson refused to extend the money, making clear his profound dissent from government policy. But by then, of course, it was too late.

Lawson’s quiescent behaviour during the design phase of the poll tax stands in stark contrast to the way Heseltine was behaving in the same period over Westland. The Westland affair is one of those political events whose high-wire dramatics are hard to reconstruct because the stakes appear so low. The question of who should bail out a West Country helicopter company looks far less consequential in hindsight than the fate of the poll tax. But at the time the danger to the government was much more serious. Heseltine staked his career on the issue because he felt it touched on his personal authority as defence secretary. His main rival in this matter was Leon Brittan, newly arrived as secretary of state at the Department of Trade and Industry after his demotion from the Home Office. Brittan was feeling bruised; Heseltine was restless and looking for new worlds to conquer. As defence secretary, he believed, ‘I can have my own industrial policy.’ In the case of Westland, this meant putting together a European-wide, state-sponsored rescue package for the UK’s only helicopter manufacturer. Brittan, though at least as pro-European as Heseltine, wanted more of a market-based solution, which included being open to a buy-out from a US private defence contractor, the Sikorsky Aircraft Corporation. Brittan was at this point far more dependent than Heseltine on Thatcher’s favour and he certainly knew which option she would prefer. Heseltine fought back with everything at his disposal, badgering his cabinet colleagues, briefing the press and threatening to resign if he didn’t get his way.

Nonetheless, there was widespread astonishment when he did quit. Many in the government remained unclear what Heseltine was getting so exercised about: when he tried to secure the services of Thatcher’s deputy, Willie Whitelaw, to broker a last-ditch compromise his messages went unanswered because Whitelaw was playing golf. (Powell later claimed that the level of detail required to grasp the Westland affair was so great that Whitelaw never managed to understand it.) Those who did recognise the strength of Heseltine’s feelings and the threat it posed – including Thatcher’s press secretary, Bernard Ingham – tried to match him at his own game, leaking hostile material to the press in order to take the wind out of his sails. One of these leaks was a letter from the solicitor-general accusing Heseltine of ‘material inaccuracies’ in a statement he had made about the respective bids for Westland. The Sun ran the story on its front page in early January 1986 under the headline ‘You Liar!’ (‘Tarzan gets rocket from top law man’). Two days later Heseltine walked out of cabinet, declaring ‘there has been no collective responsibility in the discussion of these matters. There has been a breakdown in the propriety of cabinet discussions.’ Within a fortnight Brittan was gone as well, after his department’s officials got fingered for the leak. The trail from the DTI led back to Number 10, given Ingham’s fingerprints were also all over it. His job was now on the line. So too, for a brief moment, was Thatcher’s.

Moore is very good at finding his way through the detail to capture the toxic mix of amour propre, political posturing and institutional inertia that nearly brought down the government. (One inescapable fact is that it couldn’t have happened in the age of the mobile phone: too many of the key players – not just the golfing Whitelaw – were hard to get hold of at crucial moments, so no one bothered to try.) The Westland affair gave Thatcher the most dangerous twenty minutes of her entire premiership. It occurred on 27 January 1986, following Brittan’s resignation, when the Commons held an emergency debate on the sorry saga. Both Brittan and Heseltine were present and Thatcher was vulnerable to anything they might say, since both knew how complicit Number 10 had been in their downfall. Thatcher’s defence of her own actions rested on some creative ambiguities and as a lawyer she knew that she would be exposed by a forensic cross-examination. Instead, she faced Kinnock. As Moore tells it: ‘Although he got in a few pertinent questions, he was quickly blown off course. He comically said “Heseltine” when he meant Westland, got flustered, accused the Tories of being dishonest, and tangled with the Speaker. Then he fell back upon the rhetorical generalities for which he was well known.’ In the words of Alan Clark: ‘For a few seconds Kinnock had her cornered, and you could see fear in those blue eyes. But then he had an attack of wind, gave her time to recover.’ Moore also quotes Tony Blair, who was sitting in the chamber as a young MP, taking note: ‘It needed a scalpel. All she got from Neil was a rather floppy baseball bat.’ Once it was clear she had escaped, Heseltine and Brittan each made mildly grudging statements of apology and regret. She always was lucky in her opponents.

Westland provides one of the very few laugh-out-loud moments in the book. On the weekend before the Commons debate, when her advisers were frantically helping her to prepare her defence, Thatcher had to break off to attend a constituency function in Finchley. On her way there she was told that a local party dignitary who had been expected to greet her would not be doing so because he was having a nervous breakdown. ‘He’s having a nervous breakdown!’ she exclaimed. ‘What about me?’ Yet it is testament to the essential unfathomability of her character that it’s hard to tell whether or not she was joking. Was this a touch of gallows humour? Or was it a genuine whine of self-pity? Moore doesn’t spend much time trying to dissect her personality, on the grounds that what was most interesting about it was on the surface. But he does devote a chapter to recounting the failure of her enemies to understand her properly. By the mid-1980s hatred for Thatcher herself as well as what she stood for had become something comfortable and familiar to those on the other side of the political divide. As Ian McEwan wrote after her death in 2013: ‘It was never enough to dislike her. We liked disliking her.’

Moore is surely right when he says this led many on the left to mistake the nature of the challenge they faced. ‘Since they thought Mrs Thatcher and her cronies were wicked, they tended to think they only had to point this out loudly enough and voters would desert the Conservatives. Never … did they coldly analyse why she was winning, in order to ensure she would lose.’ Moore also criticises the raft of state-of-the-nation novels and plays that purported to explain what Thatcher was doing to the country but succeeded only in raging against her. ‘There is no reason, of course, why novelists should have felt under any pressure to be pro-Thatcher, but it is interesting that they seem to have felt strong pressure to be anti, and disappointing artistically that they made so little effort to address what underlay the changes in both British society and the wider world in her time.’ One exception to this is Alan Hollinghurst, whose vignette of Thatcher at a mid-1980s private dance in his novel The Line of Beauty (2004) remains as evocative as anything ever written about her: ‘She came in at her gracious scuttle, with its hint of a long-suppressed embarrassment, of clumsiness transmuted into power.’ Moore writes approvingly: ‘This observant if superior way of describing Mrs Thatcher suggests how fruitful might have been fiction which imagined the circumstances and feelings of her and those like her as they fought to rise in the world.’

Yet Moore doesn’t live up to his own observant if superior advice. This book does little to make sense of the changes that were happening in Britain, preferring to take the Thatcherite perspective at face value: the country was doomed unless it toughened up and all views to the contrary were simply more evidence of the rot that had to be excised. Moore makes no effort to consider the reasons underlying the strength of opposition to Thatcher, or to address the diversity of its sources. Not everyone who was uncomfortable with what Thatcherism was doing to British manufacturing, for instance, was blinded by hatred of the woman herself.

Moore also fails in this volume to capture what made Thatcher’s own journey through British society so revealing. In his first volume he was forced to confront the question of how a girl from Grantham could end up as prime minister, which meant he had to explore the different worlds through which she moved, from provincial Methodism to Oxford snobbery to the legal profession to North London Jewry to the educational establishment and so on. That made it a much better book. Here he falls back too easily into his comfort zone of rival Westminster worldviews and clubby Whitehall intrigue. Because the woman at the heart of it all remains unfathomable, the picture he paints is a superficial one.

Moore may not plumb the depths of Thatcher’s personality, but he certainly captures its force. Reading this book is an exhausting experience because being around Thatcher was exhausting. People were frightened of her, not so much because of what they feared she might do to them (there is very little sign of malevolence or capricious cruelty) but because of her capacity to treat them as though they weren’t really there. Sitting next to her at dinner seems to have been a prospect of dread for many, because she really did go on and on. It didn’t matter who she was talking to (Reagan or Gorbachev were just as likely to be on the receiving end as some lowly functionary), if she got her hooks into a subject she could keep at it for hours until her interlocutor was bludgeoned into stunned submission. This Hitlerian tendency was indulged up to a point by her fellow world leaders, since they didn’t have to endure it very often (though it could make being cloistered with her at a Commonwealth or European summit a pretty uncomfortable experience). For her more intimate associates, it was simply the price to be paid for being close to the source of power.

It grew increasingly intolerable for a number of them, though, especially her foreign secretary Geoffrey Howe, whose job required him to soothe the bruised feelings she left in her wake. Yet, in the period covered by this book, he just about tolerated it. Many of her idées fixes concerned international affairs and the best way to deal with foreigners. She was allergic to being lectured by dictators and despots about Britain’s responsibilities, believing it was their job to be lectured by her. This meant that Europe was less a bone of contention than the Commonwealth. On European matters she could still be reasonably pragmatic, so long as she felt Britain was getting some value for money. But when it came to being expected to play nicely with African leaders and other representatives of the victims of Britain’s imperial past, she dug in her heels. She didn’t believe that Britain had anything to apologise for. As a result, she didn’t share the Foreign Office view concerning the appropriate response to emotional blackmail. They wanted her to negotiate. She wanted them to yield.

These tensions came to a head over the question of South Africa. Her fellow Commonwealth leaders – including the Canadian and Australian prime ministers – had been pressuring Britain to join in international sanctions against the apartheid regime. Thatcher refused, claiming that economic sanctions would only punish the people they were designed to help (the black majority), thereby making a violent breakdown of order more likely. She was mistrustful of the policy briefings she was getting from the Foreign Office, suspecting they were infected with liberal bias. She preferred the advice coming out of the cabinet’s policy group on South Africa, which had been asked to estimate the likelihood of various future scenarios for the country. It believed that by far the most probable outcome was ‘a long-drawn-out civil war’ (55 per cent). The chance of a ‘black revolutionary takeover’ was estimated at 10 per cent. ‘Peaceful transition to black majority rule’ was put at ‘perhaps 5 per cent’. She also listened to Laurens van der Post, who told her that sanctions were ‘immoral’ and the key was to ‘get a majority against the extreme blacks by forming an alliance of Whites-Indians-Coloureds-Zulus-S. African Swazis’. In the light of this, Thatcher had no wish to join in an international moral crusade. Nor did she think that Britain had any special obligation to do so simply in virtue of its position as head of the Commonwealth. She tried to treat her fellow Commonwealth leaders as she had treated the miners: she affected to rise above it all, insisting that their infighting was not primarily her concern. It was not the British Commonwealth, she told an interviewer from the Sunday Telegraph. ‘It is their club. It is their Commonwealth. If they wish to break it up, I think it is absurd.’

Not only did these interventions infuriate Howe, who spent his time in Africa being told the British were ‘defenders of apartheid’. They also risked upsetting the queen, whose affection for the Commonwealth was widely known. This threat Thatcher did take seriously. She was always very conscious of constitutional proprieties. It didn’t stop her lecturing the queen at their weekly meetings, but that may have been more out of nerves than bombast. Heseltine once asked the queen if she felt as Queen Victoria did about Gladstone: ‘He speaks to me as if I were a public meeting.’ No, the queen said, ‘it wasn’t at all like that … but I wasn’t given much encouragement to comment on what was said.’ Fear that the press would go to town on stories of a rift with the palace persuaded Thatcher to soften her approach, though not her position. As a sign of how much more willing she was to accommodate European than African influence, she said she would allow Britain to join the largely symbolic sanctions regime approved by the EEC at The Hague if every other European member state did the same. She gave way but she never backed down.

Like many long-serving political leaders Thatcher became increasingly convinced that personalities not policies were what mattered in international politics. She believed that everything depended on getting the right person at the top. She was genuinely optimistic that with Gorbachev in charge change might come to the Soviet Union; she was equally hopeful that new leadership in South Africa might make all the difference. P.W. Botha was not going to reform, no matter what pressure came from the outside world, but one of the next generation of politicians, such as F.W. de Klerk, just might.

Because this is the second volume of three, and it ends arbitrarily with Thatcher’s decisive victory at the 1987 election, it’s hard not to read it in the light of what we know is coming. It is haunted by the ghosts of the future. Intimations of Thatcher’s own political mortality are everywhere, not least during the 1987 election campaign, when her increasing crankiness drove those around her to the brink of despair. (‘Norman, listen to me, we’re about to lose this fucking election, you’re going to go, I’m going to go, the whole thing is going to go,’ David Young, the secretary of state for employment, memorably told the then party chairman, Norman Tebbit, a week before polling day. He said this not because there was any sign that the voters wanted Kinnock as prime minister but because Young had been spending too much time with Thatcher to believe they could still want her; luckily for him, they only had to put up with her on their TV screens.) The really ghostly presence, however, is John Major, the man who was destined to replace her, after first Howe and then Heseltine had wielded the knife. Though Major is barely three years from becoming prime minister by the end of this volume he barely merits a mention in it. Thatcher first properly notices him right at the end, during the 1987 election campaign, when he appears at her daily press conferences as the minister with responsibility for social security. Rosencrantz is going to inherit the crown, but you wouldn’t guess it from anything here. Those jostling to be first in line to replace Cameron should take note.

There are other eerie presentiments of current politics. Brittan, when he falls, is pursued from office by nasty rumours about his sexual history. There is nothing in Moore’s account to give them much credence but plenty of evidence of the equally nasty undercurrents that may have fuelled them. At the time of Westland, when the backbenches were starting to chunter that Brittan was not sound, Alan Clark picked up on the word coming out of the 1922 Committee: ‘Too many jewboys in the cabinet.’ Brittan may also have been the victim of Cold War dirty tricks. Michael Bettaney, the MI5 officer caught trying to spy for the Soviet Union, was said to have revealed in the course of his interrogation that ‘Moscow had information about Mr Leon Brittan’s life that laid him open to blackmail.’ When the cabinet secretary checked with MI5 he discovered that Bettaney had said no such thing, but merely by inquiring he helped to keep the whispers alive. Most conspiracy theories have long roots, and they fold back into earlier conspiracy theories, so that the point where one ends and another begins is hard to discern. Anti-Semitism is almost always part of the mix.

The contemporary politician who is most present in these pages is Jeremy Corbyn, despite the fact that his name never comes up. Corbyn first got elected to the Commons in 1983 and for the duration of Thatcher’s second term in office was a minor player on the other side of every major domestic battle she fought, manning the barricades. Indeed, he represented her enemy within. For Thatcher, the IRA, the NUM and the hard-left Labour councils were all of a piece: each sought to supplant parliamentary government with direct action and threats of violence. At the 1984 Conservative Party conference in Brighton she had been planning to deliver a stinging attack on Scargill and the NUM leadership, whom she regarded as ‘an organised revolutionary minority’ determined to subvert the rule of law. She intended her audience to understand that what she had to say applied to Ken Livingstone’s GLC as well. When an IRA bomb exploded in her hotel the night before she was due to give her speech, nearly killing her and succeeding in killing five others, she was determined to give it anyway. She didn’t feel any need to change it: she could simply extend what she wanted to say about the NUM and the GLC to include the IRA. She told the shellshocked delegates: ‘The nation faces what is probably the most testing crisis of our time, the battle between the extremists and the rest … This nation will meet that challenge. Democracy will prevail.’ They thought she was talking about her would-be assassins. In fact she was just reading the words that had been written before the bomb went off.

Corbyn would have agreed with her – not about what counts as democracy, of course, but about the linkages between her most militant opponents. The NUM, the GLC and the IRA had a common cause in his mind as well. Her enemies were his friends; his friends were her enemies. Corbyn was, and is, her mirror image, joining together the same dots as she did to produce the inverse of her tightly organised worldview. In the first chapter of this book, attempting to identify the consistent set of values that guided her actions, Moore calls Thatcher a liberal imperialist. Corbyn is an anti-imperialist. Thatcher sided with American power; Corbyn with those he considers the victims of American power. Thatcher befriended Saudi Arabia and its royal family, whom she viewed as useful trading partners and a force for stability in the Middle East; Corbyn used his first conference speech as leader to launch an attack on the Saudi regime for its abuses of human rights. (His friends in the region are the Iranians, whom he sees as trying to emerge from a history of colonial exploitation.) Thatcher was determined to keep hold of Trident. Corbyn will do whatever he can to get rid of it. The people who voted for Corbyn in the Labour election did so for a wide variety of reasons: taking up the fights of the mid-1980s mattered for some of them, but perhaps not many, and only those with long memories. A great deal has changed since then. But some things haven’t: the Conservative Party is still never happier than when Labour has a unilateral disarmer as its leader.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.