‘Splendid specimens of the untrousered, strong-legged Celt’. That was what John Stuart Blackie, the founder of Scotland’s first chair of Celtic studies in 1882, liked to see about him in the Highlands. In Celts: Art and Identity (at the British Museum until 31 January, then at the National Museum of Scotland from 30 March until 25 September) he would have met several untrousered, strong-legged giants. But Blackie would have been shocked to learn that these towering stone warriors come not from Scotland but from Germany.

This is a show which makes its way across two quaking bogs of controversy. What does it mean to call the European Iron Age ‘Celtic’, and why does much of the modern world use the ‘C’ word for a handful of Atlantic communities and nations? These are questions about archaeology and cultural continuity. But they are also smoking-hot references to politics. Was Europe already united long ago, and did Britain belong to that unity? And who do the pesky Scots and Welsh think they are?

The first thing to say about Celts is that it is visually marvellous and overwhelming. The British Museum and the National Museums of Scotland between them have brought together from all over Europe objects so splendid, famous and precious that I’m astonished their home curators ever let them travel. The second thing to admire is how careful the organisers have been with words. Neither Celtic Twilight nor Celtic Fringe is mentioned, thank God. And there’s no attempt to make the evidence fit some sexy agenda. Lessons have been learned from the vast I Celti show in Venice in 1991, which pulled out all the Euro stops: as the catalogue boasted, ‘it was conceived with a mind to the great impending process of the unification of Western Europe … the truly unique aspect of Celtic civilisation [was] … being the first historically documented civilisation on a European scale.’

None of that ‘Iron Age Maastricht’ stuff in London. The organisers have not let themselves be swamped by recent waves of anti-Celtic revisionism (‘no such people existed: Celticity only invented yesterday by sentimental nationalists’), but they have taken some healthy drops of it on board. For them, the peoples who lived north of the Graeco-Roman Mediterranean probably spoke languages derived from the same Indo-European family, and their arts were influenced in different ways by similar visual fashions and tastes. Variants of a warlike hero culture occurred from Spain through Gaul and the British Isles to Bohemia and beyond. But that’s about it. A single ‘Celtic civilisation’ in a united Iron Age Europe never happened, and those tribes never thought of themselves as ‘Celts’. Their unity existed only in the minds of outsiders, Greeks and Romans who ‘othered’ them all together as un-Mediterranean.

Something similar went on in modern Great Britain. It’s true that in Ireland, Wales and to some extent Scotland a Celtic continuity was reinvented during efforts to restore a sense of political identity. The exhibition shows this well, from the Dublin statue of the dying Cuchulain in the General Post Office to the eerie elongations of Margaret and Frances MacDonald’s graphics in Glasgow. But expressions like ‘Celtic nations’ and ‘Celtic Fringe’ are really English statements about England. Like Romans and Greeks, the English have had to invent a collective Other in order to recognise themselves. The truth is that Ireland and Scotland have long ceased to feel ‘peripheral’ to an imperial ‘core’. The main thing that those Atlantic nations and communities have in common is not Celticity. It’s their experience of English expansion.

The section of the British Museum show dedicated to the ‘Celtic revival’ confines itself almost exclusively to art and decoration, especially Scottish. That means the Ossian cult, the gorgeously sentimental myth-paintings of John Duncan, the swooping Iron Age interlace on Archibald Knox’s silverware for Liberty. Cautiously but understandably, the curators avoid neo-Celtic politics. Within the British archipelago, imagined Celtic pasts reinforce mild, left-of-centre versions of nationalism. Elsewhere, however, Celtic symbols belong to the extreme radical right, even to neo-fascists. In France and in Germany, the Celtic cross has been the badge of racist and authoritarian movements. Often, Celtism has stood for a rejection of urban civilisation and the whole rational tradition of the Enlightenment, in favour of a ‘blood and soil’ dream of rural purity. The Breton movement emerged as a conservative, royalist, Catholic reaction against the Jacobin centralism of the French Revolution. Crushed by the Revolution’s armies (‘le génocide franco-français’), it reappeared in the 1930s in opposition to the left-wing Popular Front and with some sympathy for Nazi racial doctrine. And in the United States, a few years ago, Senator Trent Lott tried to mobilise the Scottish diaspora in the South around the notion of the Celt as untamed individualist: gun-loving, tax-refusing, aggressively male and – of course – white. Why in Brittany and Mississippi – but not in Scotland? All three places developed myths of victimhood, which in the case of Scotland centred on the Gaelic, ‘Celtic’ population which was destroyed by the Highland Clearances. But Scots have never seriously claimed to be an ethnic unity. Content to be a mongrel nation, they locate identity more in history or achievement than in biology or language. Colonel Robert Monro of Foulis, that old warrior of the Thirty Years’ War, said that the Hanseatic city of Stralsund was lucky to get a Scottish garrison and governor ‘of the onley Nation that was never conquered’.

Nothing about the warlike qualities of Celts. And yet, looking round this show at the stone soldiers with their bulging thighs and mad headdresses, at stacks of bronze cauldrons for gorging hundreds of guests with beef stew, or at the kilos of gold recklessly slung around the necks of men, women and horses, you end up thinking: Yes, Asterix! After all, it’s the two French cartoonists, Goscinny and Uderzo, who got the measure of these pugnacious societies of boasters and feasters. Odd that both their names sound Polish and respectively mean ‘hospitable’ and ‘the thump of a fist’. Odd, because so Asterix.

Some of the Asterix books are on display here. They are fun, but they are also a way of defusing some antique French myths about Gaulish origin. I only wish there had also been space to include a few samples of Czech Celtomania. This is a cultural movement which is out to persuade Czechs that they are not really Slavs at all, in spite of their language, but Celts – descendants of the Boii (Bohemians) registered as Celtic by Roman writers. Once Czech intellectuals adored the culture of pan-Slav Russia. But Stalin and then the 1968 Soviet-led invasion convinced them that Slavdom was a bad call. To be Celtic, in contrast, means to be Western – part of the democratic end of the continent. It’s a bizarre, shape-shifting enterprise. But the movement produces sculpture, paintings and shelves of bodice-ripping fiction about the Czechs’ glorious Celtic past.

Some of the work in the show is figurative – the warrior statues, the stylised birds and beasts twined in the metal foliage of swords, shields and battle trumpets, or illustrated on the pages of Christian gospels. But this is above all the first age of abstraction. An incredible cultural confidence produced these geometrically balanced coils, curves, interlaced spirals and enamelled bosses, done in sheet bronze or gold, later in recycled Roman silver, finally on early medieval vellum. The Battersea Shield, dredged out of the Thames in 1855, is the emblem of the exhibition. I’d guess it’s the most perfectly designed example of ‘the Celtic arts’. And yet a shelf of tiny coins is even more significant. The model is a classical coin, bearing maybe Alexander’s head or a chariot. But the British or Gaulish die-maker doesn’t see ‘likeness’. He sees rhythmic shapes. Alexander’s features dissolve into rods and spirals; the horse’s legs float off and become wriggly, dancing shapes reeling round a detached chariot wheel. Abstraction, which took conscious effort for 20th-century modernists, came naturally to these non-literate metalworkers.

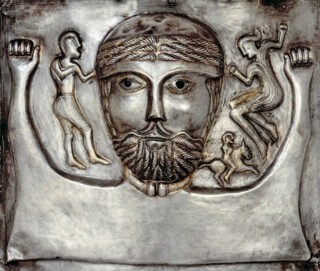

The best thing in the show is also the strangest. The Gundestrup Cauldron is the most magnificent single artefact recovered from Europe’s Iron Age. It’s an enormous silver basin, decorated inside and out with the masks of gods and goddesses, with busy human figures, with fantastic animals real and mythic. But we have no idea what it’s all about. Once there was a people who would have laughed, pointed and told their children the tale of the jumping-down girl, of the goddess between two elephants, of the antlered god with a torc in one fist and a horned serpent in the other. But they were people who didn’t write, and their stories have gone silent for ever. Neither do we know what the cauldron was for. It was found in a Danish bog but is thought to have been made in the first century bc in Thrace. Only some details – the style of beards and hair, the trumpeters blowing the carnyx war-horn found in Gaul and Scotland – connect it firmly to the ‘Celtic’ cultures of the West.

We can’t read their beliefs and we can’t see through their eyes. ‘Double-disc and Z-rod’ categorises exquisite Pictish symbols – look out for that tiny silver pendant from Norrie’s Law – but can’t interpret them. So the gaps in knowledge are colonised by our own self-projections: Celts as untrousered children of Nature, or untamed frontiersmen, or merely as those marginal Brits who for some reason like not being English.

But stumbling out of this exhibition, you begin to wonder who is peripheral to what. Maybe it’s the stolid, literal-minded Romans and Anglo-Saxons who are the real fringe folk. Maybe we should pity them, because they never quite made it to becoming Celtic.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.