The little pub is still there, the Myddleton Arms, and in front of it the zebra crossing on the Canonbury Road. I came out of the pub that evening in early December 1962, and stopped as the door closed behind me. There was no crossing, no beacon pole. I could make out the paving slabs gleaming wetly under my feet, but not the kerb. With a painful jolt, I stumbled into the roadway. Shuffling forward into the thick yellow murk, I suddenly saw what looked like a row of orange pips hung across the street. I kept moving towards them until I collided with something wide and hard: a vast object which turned out to be a London bus, slewed across the street and abandoned by passengers and driver. The orange pips were the bulbs of its lower-deck lights. It was quiet but not soundless. It was like the H.G. Wells story in which time is slowed down until sounds disintegrate into separate beats. Cars revved somewhere; a lorry far over towards Shoreditch hooted. A distant alarm pulsed. Across a distance which could have been far or close came the tap of a stick, then a few footfalls which died away.

That was the very last London fog. Children in Bow had to sleep in their classrooms. Thousands of empty cars were left blocking the North Circular. The Duchess of Kent was unable to reach her flight at Stansted; the prime minister failed to get to a dinner at the Savoy. A monkey got lost in Oxford Street, and a Slavonian grebe – trying to migrate without sight of ground or stars – made a forced landing in Regent Street. At Richmond, a man cycled into the river. There was a wave of burglaries.

There were 750 deaths attributed to the fog. This was low compared to the penultimate ‘Great Fog’ of ten years before, which is supposed to have killed more than four thousand people. But the ‘killer fog’, and especially its increasing component of sulphur dioxide, raised a much greater public uproar than its predecessor in 1952. The papers complained that it should never have happened: hadn’t the Clean Air Act been in force since 1956? But this fuss, and the better enforcement of smoke control measures and smokeless-zone regulation, ensured that 1962 would be the last of the classic London fogs. From the late 1960s, the smog of hydrocarbon vehicle emissions became the main threat to London lungs. The ‘London Particular’, the ‘pea-souper’ that was the city’s brand for so many centuries, has not been seen since, and – logically, scientifically – should never be seen again. But then, that’s what they thought before 1962.

Christine Corton’s excellent book explores three questions: how people accounted for London fog, what they did about it, and how it became such an enormous, apparently inexhaustible cultural resource and metaphor. Liability to fog has ultimately something to do with London’s position in a river basin, hemmed in to the north by hills. The atmosphere was already thickening in Tudor times, as Queen Elizabeth declared herself ‘greatly grieved and annoyed with the taste and smoke of sea-coles’. Then and in the 17th century, industry was blamed; wood-smoke from lime-burning and fumes from coal (‘sea-coal’) burned in breweries, bakeries and glass foundries. John Evelyn’s Fumifugium, or, the Inconvenience of the Aer and Smoak of London Dissipated (1661) dismissed the idea that domestic hearths had much to do with it – probably correctly at the time.

Evelyn wrote about ‘Clowds of Smoak and Sulphur, so full of Stink and Darknesse’, and he noticed that the polluted air was ‘super-inducing a sooty Crust or Fur upon all that it lights’. (Here, exactly, was that London which endured down to and beyond the moment I first glimpsed it in wartime: a city of mourning-black temples whose columns and arches were wrapped in inky, velvety fur. Who under fifty, knowing only this golden-scrubbed city centre, can imagine that?) Evelyn’s idea of a cure was to drive smoky industries out of London and surround the town with a sweet-smelling hedge. Nothing was done. But Evelyn’s emphasis on factories was the beginning of four hundred wasted years of blame game between the industrial lobby and those who proclaimed the increasing danger to public health and to normal urban life. Especially in the Victorian and Edwardian years, politicians took every kind of evasive action to avoid the thought that domestic coal fires – the sacred family hearth itself – rather than factory chimneys might be the critical source of London fog. As a journalist wrote in 1822, every proposal for smoke control was resisted by ‘smoke-burner’ MPs in the industrial interest, and when each parliamentary recess arrived, ‘we relapse into our pristine fuliginosity.’

As the 18th century ended, London was already referred to as ‘the Smoke’, and the fogs were growing more frequent and denser. Their colour began to darken from the yellow of sulphur to brown and even black, as the load of soot particles thickened. An act summoning furnace-masters to modify steam engines and induce them to consume their own smoke was ineffective. Once again, Parliament was addressing the less important source, but – with England’s forests mostly cleared – no alternative to coal for heating and cooking yet existed for London’s growing population.

Temperature inversions – when an upper layer of warmer air prevents colder, polluted air underneath from dispersing – produced fogs of almost complete darkness in daytime, as the soot content of London’s air grew more concentrated. Londoners became used to washing the greasy deposit of soot out of their clothing after a fog, and they assumed it was normal to spit black when they coughed. More than a century later, the future politician Chris Prior took off the mask his mother had given him during the 1952 fog and found it coated with a brown goo ‘like Marmite’. Manchester, when I worked there in the 1950s, was not much better, and I grew inured to the black stains left on my handkerchiefs.

In the Romantic age, fog was mocked but also celebrated. Byron, in Don Juan, proposed the metropolis as ‘a huge dun cupola, like a foolscap crown/On a fool’s head – and there is London town’. Literary description of fog became an enjoyable duty for visiting writers. So, too, did dramatic pen-pictures of the dome of St Paul’s, rising out of the smoke-clouds. Here in the 1830s was born the beloved and constantly repeated trope (unconquered England, rising above the storms of history) which culminated in that tremendous 1940 image: the dome of St Paul’s emerging above the fire and smoke of the Blitz.

Names for the fog evolved during the 19th century. ‘Pea-souper’ is sometimes attributed to Melville, who wrote in 1850 of encountering ‘the old-fashioned pea soup London fog – of a gamboge colour’. This suggests that the expression was already well-worn. (Corton, given to rather engaging fits of pedantry, here goes off into a disquisition about dried pea varieties, soup preparation and the diet of the Victorian poor. She also points out that thick yellow fog had a distinct taste, and that some Londoners and visitors, impressed by the gamboge-coloured pease pudding, played with the idea that fog might actually be nourishing.) ‘London Ivy’ was another term. The word ‘smog’ was invented in 1904 to describe fog by the ‘Smoke Abatement’ campaigner Henry des Voeux, and transferred only later to chemical air pollution by powered traffic. ‘London Particular’, on the other hand, had a much longer history. Charles Dickens is supposed to have thought it up for an 1851 article about conditions in Spitalfields, quoting a weaver who complained of a ‘black London genuine particular’ which stained clothes. He repeated the phrase famously in Bleak House. Corton, however, finds it in the caption to an 1827 cartoon by Michael Egerton (her selection of London fog illustrators, from Cruikshank to David Langdon, adds entertainment and insight all through the book.)

Corton salutes Dickens’s mastery of ‘the use of fog as extended metaphor’. And of course no fog in literature approaches that introduction to Bleak House with ‘Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows, fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollution of a great (and dirty) city …’ Fog, ultimately, swaddling the High Court of Chancery, ‘most pestilent of hoary sinners’. To say that Dickens multi-tasks his metaphor is a hopeless understatement. To choose a few allusions from those pages, fog stands for the end of the world, for cruel poverty, for undeserved sickness, for reversion to an age of dinosaurs, for the unnaturalness of cities and industries, for impenetrable arrogance and stupidity.

A specially lurid use, picked out by Corton, is fog as rapist and murderer. In Our Mutual Friend, Dickens placed ‘a sobbing gaslight in the counting-house window and a burglarious stream of fog creeping in to strangle it through the keyhole of the main door’. Dickens used fog as a vehicle for revenge, as the dissolution of the individual, as a general indeterminacy in which transformations happen. There seems to be nothing the man couldn’t do with this stuff which, as Guppy in Bleak House complains, ‘smears, like black fat’.

Peak fog was reached in the 1880s. Since about 1840, the city’s population had been multiplying steeply, and by 1880 there were three and a half million fireplaces in the city burning cheap coal, their users often keeping fires and ranges going overnight by loading them with smoke-gushing slack. Coal imports to London rose from five million tons in 1862 to eleven million twenty years later. There was a 200 per cent increase in mortality during the 1879 fog, and in 1886 it was estimated that bronchitis deaths reached some seven hundred a week in fog periods, which were becoming more frequent. Between 1881 and 1885, London averaged 55 foggy days a year; between 1886 and 1890, that had risen to 63.

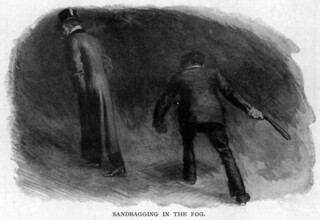

These mortality statistics released a fresh burst of health warnings, from the British Medical Journal to the bestselling pamphlet London Fogs by Rollo Russell, son of the former prime minister. They also ignited imaginations. Fog was now invoked to symbolise social breakdown and the collapse of deference and civilised order. The 1886 fog coincided with an orgy of looting, the stoning of West End clubs and rioting in Trafalgar Square and elsewhere in London. The ‘link boys’, who had always guided coaches and pedestrians through fog behind flaming torches, were now suspected of leading their clients into footpad ambushes. Pundits began to talk about the moral and physical degeneracy of the poor brought on by bad health, which in turn was partly caused by foul air.

Writers grew interested in the sensations of young, vulnerable women wandering alone in the gloom. In The Portrait of a Lady, Henry James sends Isabel Archer boldly marching by herself through the ‘thick brown air’ from Euston to Piccadilly. Corton, however, suggests that the fog is ‘a metaphorical representation of this lack of light in her life, the obscurity of her emotional future’. Not for the first or last time in this book, Corton’s adventurous decrypting of meanings strays off into a pea-souper of her own making. In The Princess Casamassima, she finds two women ‘trapped in the fog of a false ideology and false moral values’. James, admittedly, was fascinated by fog. It meant that London was ‘still exhaling its queerness’ and it seemed to him to have an almost protective aspect in the way that it elided any sense of time and even of season.

Corton has assembled an astonishing display of fog fiction. She uncovers a shelf of forgotten ‘Doom of London’ novels, in which thousands or millions perish as order dissolves and brutish immorality surges through the mist from choking slums. In almost all this literature, some of it of quality and some pulp, the fate of women in fog is central to the plot. Sometimes they are raped by the mob or – after the Whitechapel murders – ripped and strangled. But sometimes fog’s concealment gives a woman a moment of freedom in which she can escape her assigned role (Hester Oakley’s ‘Love in a Fog’, in which an unrecognised princess connects with an unknown stranger who rescues her in the street, is a graceful example). H.G. Wells, in Love and Mr Lewisham (1899), describes how fog turns ‘every yard of pavement into a private room’: ‘one could do a thousand impudent, significant things with varying pressure and the fondling of a little hand.’

Fog, in this school of fiction, empowers the male. ‘For women,’ Corton writes,

London fog posed a threat, increasing the risk of male violence, of murder and rape. It blurred social and moral distinctions, and if … it provided a welcome anonymity for love and romance, it still contained dangers that required the presence of a male protector. In a world reduced to a state of nature or regressed by fog to prehistory, the strong man was king.

Foreign visitors to Victorian London let all their metaphors out to rampage. Hippolyte Taine: ‘At thirty paces a house or a steamship look like ink-stains on blotting paper … after an hour’s walking one is possessed by spleen and can understand suicide.’ Nathaniel Hawthorne experienced fog as ‘the ghost of mud, the spiritualised medium of departed mud, through which the departed citizens of London probably tread in the Hades whither they are translated’. James Whistler came from America, Petersburg and Paris to paint Nocturne in Grey and Gold, Piccadilly (c.1882), the boldest stroke of 19th-century fog art. Claude Monet, working from a room in the Savoy Hotel or from St Thomas’s Hospital, produced nearly a hundred paintings of fog around Thames bridges and the towers of Westminster. His worst moment came one day when he got up to find the air perfectly clear: ‘I was terrified to see that there was no fog, not even the least trace of a mist; I was in despair … but then little by little, as the fires were lit, the smoke and the mist returned.’ This sort of fogolatry made Oscar Wilde observe that London fogs ‘did not exist until Art had invented them. Now, it must be admitted, fogs are carried to excess. They have become the mere mannerism of a clique.’

Joseph Conrad used fog judiciously but to fine effect when writing about London. The Secret Agent is infested with it. Corton suggests, plausibly this time, that ‘fog signifies the blurring of Verloc’s and Stevie’s moral perceptions and the confusion of identities.’ She is on thinner ice, though, when it comes to Conan Doyle and Sherlock Holmes. Fog is everywhere in those stories, as she rightly points out, but it’s pushing critical sense to say that fog ‘can represent Holmes’s state of mind before he finally clears up a mystery’, or that it is ‘a signifier of Holmes’s state of mind when he does not have a case to solve’.

But Corton is convincing when she points out that by now – the end of the Victorian century and the start of the next one – new elements are creeping into the way that London fog is used in fiction. One new thread is nationalistic, even xenophobic, in the years when Europe was drifting towards war and Britain was engaged in a naval arms race with Germany. Hugh Owen, in The Poison Cloud (1908), blames his exterminating fog on the import of cheap, noxious foreign coal (disloyal British miners who strike have destroyed the native industry), and it is the Royal Navy which crushes the savage East End rioters and clears the wreckage from the Thames. ‘Fog,’ Corton says cleverly, ‘has here become something foreign, to be dispelled by British military action.’

Another change, well noticed by Corton, was a growing association of London fog with the past. In the decade up to 1914, the air seemed to be growing cleaner. During the 1880s, the city had averaged sixty days of fog per year; in 1900, this fell to twenty days. Among the reasons were the spread of gas cookers, the gradual replacement of small steam engines by electric motors, better designed domestic grates and effective punishment of illegal polluters. Fogs, when they did occur, were paler and seldom developed the blackness of the old Particular. In consequence, writers who reached for the old pea-soup metaphors began to push their stories into the past. The early Sherlock Holmes stories suggested that the great detective was a moderniser, acting in the present. But when Conan Doyle was forced to resurrect him, after vainly killing him off at the Reichenbach Falls, Holmes had become a figure from older times, his feats transferred back into an age of fog and gaslight. ‘The Adventure of the Bruce-Partington Plans’, written in 1908, takes place in the 1890s. Conrad, writing at about the same time, set The Secret Agent in the 1880s. Wells staged Love and Mr Lewisham, with its foggy references, some twenty years before its publication in 1899. And, as Corton says, the cult of Dickens had grown so enormous over the years that the space for saying anything original about London fog now seemed dauntingly narrow.

But, as it turned out, the fog hadn’t gone away at all. After the First World War, it returned with all its ancient force. A very dense pea-souper occurred in November 1921, followed rapidly by a ‘brown wall’ in January 1922 and another in November the next winter. In the fog of December 1924, link boys returned to the streets of London, this time walking with their flares in front of motor cars. As T.S. Eliot evoked ‘the brown fog of a winter dawn’ in The Waste Land, a Committee for the Investigation of Atmospheric Pollution insisted that two-thirds of the problem came from domestic fireplaces.

New instruments recorded 340,000 pieces of soot in every cubic inch of air breathed by Londoners on foggy days. Lord Newton, the most vigorous campaigner against coal smoke, claimed that ‘the annual sootfall in London is no less an amount than 70,000 tons.’ But the problem seemed to be getting worse again, both in frequency and density. Was it, after all, an inseparable part of London living – even something to be proud of? H.V. Morton wrote in the 1920s that ‘the stranger in his first fog finds thrills innumerable; the Londoner, hate it as he does, cannot deny that there is a childish joy in the sudden dislocation of routine, the astonishing realisation that the other side of the road is an adventure and a peril.’

But a scientific corner had been turned. Parliament found endless reasons to delay and castrate smoke abatement bills, but by the mid-1920s, few still denied that domestic fires were the main cause of fogs. The battle was now about the right of the state to violate the family hearth. Lord Banbury, aghast, to Lord Newton: ‘The noble Lord says that he does not want a housemaid to carry a coal scuttle up two or three floors. He says there should be a gas fire. I have always believed this was a free country.’ Gradually the reformers outflanked the diehards. Gas and electricity became cheaper and easier to use. The industry and coal lobbies fought on, and in December 1926 the weakened Smoke Abatement Bill which finally limped into law left domestic fireplaces untouched. But the National Smoke Abatement Society carried on the struggle, helped by the steady conversion to gas (by 1938, less than half of domestic fuel consumption was provided by coal).

Dense fogs persisted through the 1930s. Young Eric Hobsbawm arrived in London in 1933, describing in his diary a Particular in which ‘Here am I, in my world, ten metres’ circumference. Beyond that, whiteness that sucks everything up.’ Fog set in again after the Second World War, with a devastating darkness in December 1948 that lasted for several days and paralysed shipping and airports. Then came the gigantic, climactic fog of 4 December 1952, which lasted almost a week and spread out over an area some forty miles in diameter. Solid and yellow, it stifled all transport, killed the farm beasts at the Smithfield Show and was held responsible for between 4000 and 6000 human deaths.

Angry public demands for action now became deafening. Harold Macmillan, then minister of housing, was quite put out: ‘We cannot do very much, but we can seem to be busy – and that is half the battle nowadays.’ But committees met, took evidence and recommended, and in 1956 the Clean Air Act became law, at last establishing smokeless zones across London (Manchester had had them for years). And that, for London, would have been that but for the unexpected fog of December 1962, which gassed the citizens with more sulphur dioxide but less black soot than ever before. It was the further spread of smoke-free zones during the 1960s which finally consigned the London fog to literature.

Up to then, it had remained a writer’s standby. Once again, Corton retrieves the fog fiction of the last hundred years. Fog was at the windows the night that Soames Forsyte ‘at last asserted his rights and acted like a man’ by raping his wife, Irene; Christianna Brand and P.D. James set crime to pea-souper music; Henry Green in Party Going (1939) used fog to immobilise a gang of merry young things on their way to the Continent. Evelyn Waugh, in Put out More Flags (1942), made Ambrose Silk lament England’s decline which ‘dates from the day we abandoned coal fuel’: ‘We used to live in a fog, the splendid, luminous, tawny fogs of our early childhood. The golden aura of the Golden Age … The fog lifts, the world sees us as we are and, worse still, we see ourselves as we are.’

Frank Kermode, discussing Henry Green, understood the impact of fog as ‘sensory failure … an interruption in the conventional processing of information, in our knowing dully, for the sake of convenience, where and what we are.’ That’s exactly right. Those ‘Doom of London’ novelists were spot-on to recognise that when you can’t see where you are, you can’t see who you are. In London, fog has been about fear, about the sudden solidarity of strangers and the fall of class barriers, about an eruption of crime.

Corton has written a thoughtful, vivid, very memorable book. But she could have made much more of the similarity between the fog experience and the Blitz. Then, too, people in the blackout overcame fear by linking up with strangers, as they stumbled across fallen class distinctions, threw away moral inhibitions and tried to cope with bombs and the biggest crime wave in London’s history. One-off disasters – a flood, plague or fire, even suicide bombers on the Underground – don’t modify perceptions in the same way. Fog, paradoxically, brought with it a vision: that things could be different, much worse, or in certain ways much better. London in the 21st century, as divided and ill-controlled as it ever was, could do with a new kind of Particular to fog its arrogant certainties.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.