In the final pages of The Rings of Saturn, W.G. Sebald imagined ‘the depths of despair into which those can be driven who, even after the end of the working day, are engrossed in their intricate designs and who are pursued, into their dreams, by the feeling that they have got hold of the wrong thread’. Sebald was talking about weavers, but the feeling must be common to all sorts of artists, and to researchers, too. Getting hold of the right thread when you’re trying to find out about a life or anything else is a matter of luck: you don’t know what will lead somewhere useful or join up with other threads until it does. Every time you look back over fruitless archive searches, unhelpful conversations, dead addresses, unanswered emails, the intricate design you’ve imagined becomes pointless or malign and you feel like abandoning the project altogether. I don’t know of many books that give a better sense of the frustrations and excitement of research than Julia Blackburn’s account of her attempt to find out about John Craske.

She first hears about him from her friend Emily, who told her: ‘He was a fisherman who became a painter and embroiderer … I think he’s much better than Alfred Wallis down in Cornwall, or at least he’s just as good, a bit different, less savage. Wallis was taken up by Hepworth and Nicholson and all the St Ives lot, but Craske’s been ignored.’ He proves an elusive subject. His life was almost entirely uneventful. Blackburn explains that he ‘was born in 1881 and in 1917, when he had just turned 36, he fell seriously ill. For the rest of his life he kept moving in and out of what was described as a stuporous state.’ From the age of 11 he’d been a crab fisherman, working with his father and two brothers up the east coast. Something happened to him during the war. He was called up in March 1917, but after a few weeks of training he caught flu, which caused a ‘relapse’ (of what isn’t known), and after moving from one hospital to another he landed up in the Thorpe Mental Asylum near Norwich, diagnosed as suffering from a ‘brain abscess’.

After he came home, his brothers took him out to sea again, on a trawler out of Grimsby, but he couldn’t do much except lie down below deck, unresponsive and helpless. After three months he said ‘he wanted to come home,’ and his wife, Laura, came to fetch him back to Norfolk. Back near Blakeney he was sometimes well enough to go out on still water in a dinghy, or sit in the sun carving toy boats, but he was often marooned indoors, too unwell to get up. He spent much of the rest of his life in bed. He sank into dreams which he would recount to Laura, and after one dream about his father’s boat as an image of safety in a storm, he told her he was going to paint it. From then on he painted everything he could. Every surface of the cottage and everything in it: the mantelpiece, the windowsill, the furniture, the walls, the door panels, ornaments, china – all covered with paintings of ships and the sea. When he became too unwell to get up, he embroidered pictures, propped up in bed.

Blackburn’s book is composed of digressions, an associative dérive more than a biographical account. One of the central notions is ‘drifting’, which becomes the book’s ostensible method:

I cannot find what has been lost, no matter how often I search for it. All I can do is to hold a few facts and images in my mind’s eye and let myself drift in whatever direction I am taken. Maybe that is already a way of getting closer to my subject, because John Craske knew a lot about drifting and I need to keep alongside him.

It’s probably a mistake that this paragraph is printed twice, but it’s prescriptive enough to make me wonder, all the same. There’s something mantra-like about the book, calm and circular and sometimes very sad. It’s also a ragbag of East Anglian knowledge. All of which makes the business of discovering Craske’s life complicated, while at the same time drawing the reader closer to the circumstances of Blackburn’s.

Like Sebald’s, Blackburn’s writing is meandering, concerned with the author as well as the subject – an approach she shares with the new breed of nature writers, such as Robert Macfarlane and Helen MacDonald, whose propensity for walking allows plenty of space for associative thinking and oblique connections. It also reflects habits of thought of which hyperlinking and googling are part. Sometimes, as in the work of Iain Sinclair and his imitators, there can be a kind of paranoia: everything connects up in sinister or unseen ways. In Sebald’s case, where the tone is more melancholy than paranoid, less is left out and there are more loose ends. There’s also an explicit debt to Thomas Browne, and his inclusive curiosity. Threads made me think of Thomas Nashe and his pamphlet ‘Nashe’s Lenten Stuffe’, about Great Yarmouth and the ‘praise of the red herring’. It’s hard to write about Norfolk and fishermen without mentioning herrings. Threads is no exception, but the red herring, the thread that leads nowhere, has its true origin in Nashe’s divagatory and fantastic prose. Herring fishing sustained the economy of Yarmouth until the end of the 19th century, drawing ‘more barkes to Yarmouth bay than [Helen’s] beautie did to Troy’, as Nashe puts it. In Chapter 12, spurred by a visit to the Great Yarmouth museum, where the man who sold the tickets ‘suddenly rose to his feet and spoke about the fish and their history, as if he was an actor playing the part of Chorus in a Greek tragedy’, Blackburn writes her own ‘Praise Song for the Herring’, versified from a book of 1881, which sounds a bit like Christopher Smart. And 1881 was the year Craske was born.

There are lots of short threads like this in the book: among other things, we pick up information about the Glandford Shell Museum, the Little Auk, Gilbert White, sea fishing, the Elephant Man, Edwardian Sheringham, Valentine Ackland and Sylvia Townsend Warner, embroidery technique, Edward Meyerstein, Walt Disney, the Norfolk Giant, the pituitary gland, diabetes, MI5, and Einstein, who stayed at a (not very) ‘secret location’ on Roughton Heath, near Cromer, for some weeks in 1933. In each case, the reader follows the author following a thread through extracts from letters, manuscripts, articles or books, and accounts of meetings and conversations with people communicative and uncommunicative. We also hear about her friends and relations and the places she visits as she searches for traces of her subject, or for objects or knowledge that might help bring him to life for her. The writer’s own chronological narrative lends coherence – all the chapters are dated – as if research notebooks and diaries had been brought together to record the process of writing the book. Chapter 48 begins with a notebook extract as follows:

I keep scattering into different notebooks. Sometimes wonder if I have lost the thread, if there is a thread to be lost. But every morning with the first shifting light, a thrush has been singing a wild song of almost spring and this morning a tree creeper was darting up and down the trunk of the oak tree outside the window and it made me laugh to see such erratic energy, such unconcerned upside-down-ness.

The artfulness of the book’s construction lies in the way it makes full use of its own erratic energy, jumping from place to place, time to time and topic to topic, so that by the end we have at least as strong a sense of these three years of Blackburn’s life as we do of Craske’s. The figure of Craske is constructed almost entirely from secondary accounts and correspondence – through letters written by his wife, a few newspaper reports, the writings of Sylvia Townsend Warner and Valentine Ackland, who were among his earliest enthusiasts, and subsequent correspondence from Elizabeth Wade White, another collector and supporter, and Peter Pears. Valentine introduced Craske’s pictures to her friend and occasional lover Dorothy Warren, who owned a gallery in Maddox Street (the one from which police confiscated D.H. Lawrence’s paintings when they were exhibited in July 1929): Warren was ‘enthralled’ and in August 1929 an exhibition of Craske’s paintings opened to some enthusiastic reviews, and a number of sales. Craske himself comes across mainly through his pictures. The book has more than eighty illustrations, including some thirty colour reproductions of Craske’s paintings and embroideries: boats in storms, a fishing fleet under a wintry grey sky, a trawler listing heavily in a choppy sea, often with his capitalised signature in the bottom right-hand corner. We hear his voice only occasionally, as reported speech or in the extracts from a typed-up version of his My Life Story of the Sea, which appears in a pared-down version edited by Blackburn, ‘just a few unadorned and curiously unemotional sentences bobbing about and doing their best to fend for themselves’.

Now Cod fishing

In the winter time

Is very cold work.

In a Crabboat

I have known times

When it has been blowing

And snowing and freezing

And all the time my Father

Has been rowing the Boat

Up to the lines.

It works, because of the pictures, which bear out the claims that have been made for him. The embroidered pictures are the most interesting: he started doing them in 1929, when he was, in Laura’s words, ‘so distressed … he would not settle to do anything.’ She continues:

Mother found an old frame up and then I said, ‘Mother, have you a piece of calico?’

Mother replied, ‘Only my new piece which I have bought for my Christmas pudding.’

I looked at her and she looked at me and then said, ‘Oh – let John have it!’

We tacked it onto the frame. John drawed a boat on it. We found some wools up and I showed John the way to fill it in.

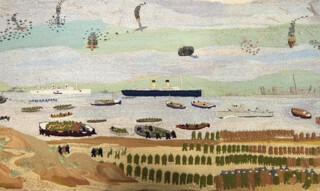

After that he worked much of the time in embroidery, producing remarkable images, moving, original and forceful. They culminated in the work he is now, at last, perhaps, becoming known for: his vision of the evacuation at Dunkirk in 1940. He was working on it when he died in August 1943; there is one patch of the sky waiting to be stitched in. It is an extraordinary thing, 22 inches wide and about five yards long, with hundreds of figures, boats of all sizes and sorts, planes, explosions, all against a landscape of sky, sea, the beach, dunes and marram grass, executed in the minutest detail and full of a sense of movement, conflict, patience and perseverance. The effect is both emotionally complex and utterly naive. It has recently been on show in Norwich and Aldeburgh. When Elizabeth Wade White wanted to exhibit it in America in 1947, the curator of the Castle Museum in Norwich wrote back to her that he was willing for it to go to New York, but ‘I do not wish to have my name associated with such an exhibition because, quite frankly, I do not think work of this type comes under the heading of art.’ It didn’t make the journey, as it was too cumbersome to transport. Townsend Warner succeeded in getting it ‘de-mothed’ a few years later, but not put on display. Nor was it available for the exhibition of Craske’s work in the Aldeburgh Festival, 1971, as Norwich had loaned it to the Glandford Shell Museum, where it stayed for several years.

Blackburn makes no claims for the importance of Craske’s art, but practically all the threads in the book have something to do with artists or the making of art, or have an art-like quality, patiently attentive to whatever improbable conjunction the drift of the research leads on to next. The energy is infectious, but the tone is melancholic. Drifting leads easily towards melancholy, and this is a sad story. Not only because Craske’s was a melancholy life but because the process of research and writing turns unexpectedly into a work of mourning, as the author’s husband, Herman Makkink, a sculptor and intimate presence in the book, dies, suddenly. On his last day there is a brief conversation between them, as she asks what she would do without him. ‘“You must work,” he said, serious in answering the seriousness of my question. “Only work will get you through.”’

Work and days, life and death, art and friendship, these are what ground the receptive, drifting quality of Blackburn’s writing. The odd state of Craske, hovering between living and dying, finds a counterpart in the north Norfolk coast, with its uncertain boundary between land and sea, as well as in the way research ebbs and flows through her daily life. ‘Often,’ Blackburn says of her search for Craske, ‘all I can find is the evidence of his absence.’ By the end, she has given us all we need to know about him, and his absence, like the absence of her husband, is an indelible presence in the world.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.