I wish someone would explain why yet another major Tate Britain exhibition has come under critical fire. The latest round of brickbats started flying a good six months before Barbara Hepworth: Sculpture for a Modern World was installed (until 25 October). Jonathan Jones already felt certain in January that the show ‘wants to free’ Hepworth ‘from any provincial status’, so as to place her works ‘alongside those of Brancusi, Kandinsky, Mondrian, Pollock, Rothko or Richard Serra’. What else to expect from curators capable of insisting that the true home of modern art was St Ives or Yorkshire? ‘Pretending that it was is complacent, insular and either intellectually dishonest or genuinely stupid.’

How dishonest are insults like these? How genuine their stupidity? To see the Tate’s Hepworth retrospective is to realise that nothing in it rides on the idea of modern art’s ‘true home’. On the contrary, the show argues that where modern sculpture is concerned there was, and could be, no such place. Hepworth’s work, it aims to demonstrate, was both a proposal and an investigation which went on imagining a new kind of existence in public: not in the world the artist knew, but in one she hoped for, ‘a modern world’ in which sculptural form might come alive through the relationships it established, the spaces it created, the sensations it explored, the depths it plumbed. The goal of such form, as Hepworth put it in 1937, is ‘the plastic embodiment of a free idea … more vividly potent because it puts no pressure on anything’.

To read the huffings and puffings in the papers is to conclude that such a ‘free idea’ is a difficult concept. Otherwise why devote precious column inches to bemoaning the fact that fragile works of wood and plaster need vitrines to protect them? Why worry that the gallery’s artificial lighting ‘imperceptibly blanches’ the work? Perceptible blanching might well be an issue, granted, but then again, much of Hepworth’s work is white and wants to be. And as for that perennial red herring, the dearth of ‘great women artists’ (apparently Hepworth fails the test), how boring is that?

The exhibition is a straightforward triumph: crisply concise, strikingly varied and often presenting material never seen before. It covers six galleries, some sparse, some dense, establishing a pace that quickens and slows through the decades. Then, with a remarkable re-creation of an exhibition pavilion by Gerrit Rietveld which in 1965 served as the setting for the first Hepworth retrospective, it comes to a stop. Outside the compass of the Tate show are the years leading up to the artist’s death in 1975, brought about by a fire started accidentally in her St Ives studio.

At the start, we find Hepworth and the other carvers of her generation – Henry Moore, Ursula Edgcumbe, John Skeaping – making common cause with a slightly older cohort, Jacob Epstein, Eric Gill, Gaudier-Brzeska, Elsie Henderson, Alan Durst. In works produced both before and after World War One, they began to remake the look and feel of the carving tradition. Dark hardwood and mottled native (i.e. English) stone were more often used than crystalline marble. The female torso stood for the human, its enforced abbreviation promising an unrealised fertility, while other carvings evoke an animal aliveness: coiled marble snake and squishy onyx toad, nervous fawn and flat finny fish, each poised to strike, leap or swim. Such objects are small by design rather than default. Intimacy was their achievement, tactility their objective, with shape and surface always appealing to the touch. For the moment, the monument was dead. Domesticity ruled, as the Arts and Crafts tradition began to keep company with modernist design. Both Moore and Hepworth showed at Selfridge’s with an eye to making an income from art.

Such small carvings speak to a middle-class life which in 1930s London was still very much in the making. For Hepworth, its epicentre was the North London studio which, until German bombs exiled them to Cornwall, she shared with the painter Ben Nicholson. The show vividly conjures the studio’s crowded, exuberant self-confidence. Paintings, drawings, prints, photographs, sculptures, textile designs, collages: all the things they made invent a specific aesthetics of intimacy, a shared exploration of what it means to love and be loved, to feel close and yet distinct, to wish to enter the other and yet be kept out. Look for instance at Nicholson’s drawings of Hepworth peering into a mirror, or follow the evolving sign he found for her profile, and then watch for it in her sculpture, as a line chased into the surface – the body – of the stone. The erotic intensity is overwhelming, and to encounter the photograph albums each partner compiled (never before shown by their heirs) is to realise how far they went on the path of shared self-exploration, as if wishing to discover whether the boundary lines between lovers could be made over as a common language of form.

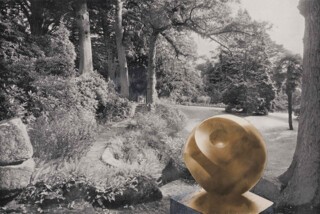

I doubt that anyone will be surprised to see that photography played a major role in the life of this artist couple, even though the evidence presented here is mostly new. Newest of all are the photographs Hepworth made of her own work. The sculptural qualities of black and white photography have seldom been more subtly mined. Light and dark gradation insists on substance, summoning the fullness of form. But not content with these effects, Hepworth went on to picture her works from different angles, and then in wonderful double exposures, to overlay selected negatives, so as to defeat the planarity, the fixity, of the photographic view. And then, as if to create an optimal world for her sculpture, she collaged photos of individual sculptures into sites of her choosing – the garden of a house on Silver Lake Boulevard, Los Angeles, designed in 1932 by Richard Neutra, for example, or the entrance to a block of flats in Zurich designed in 1935 by Marcel Breuer and the cousins Alfred and Emil Roth.

I don’t want to suggest that these collages and photographs overshadow the carvings they are based on. But they do make clear Hepworth’s concerns with her work’s possible worlds. Her tactic of putting two or three forms together (and sometimes more) also raises the question – or, better, solves the problem – of the company her sculpture should keep. Art critics usually have a lot to say about ‘internal relationships’ – what happens within a composition or frame. They find less occasion to notice that a work which materialises the physicality of relationship takes up a central reality of embodied existence, when two or three are gathered together, or when a single form stands alone. What happens within a Hepworth carving is always as important as what occurs around it. She cut deep into wood and marble, scooped out hollows within them, then strung their openings with an exactitude worthy of Apollo’s lyre. Is anyone surprised that music meant so much to her? Why was Bach her hero? Her answer is unnervingly cool: his ‘immense and neutral’ art, she wrote in 1933, was far ahead of its time. When one looks at the best of Hepworth’s work – Two Forms, or Pelagos, or Curved Form (Delphi) – a similar judgment, tinged with the same quiet confidence, seems right.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.