Sonia Delaunay – who designed clothes worn by Gloria Swanson and Nancy Cunard, whose bold zigzag textiles and liveried Citroën graced the cover of the January 1925 issue of Vogue, who consorted with Picasso, Derain and Braque and criticised all of them – was born in 1885 as Sara Stern, one of five children of a Jewish foreman in a nail factory in Odessa. But there was a rich uncle in St Petersburg, and an aunt who couldn’t have children of her own. Something about her sparkled, and she was the daughter who was spirited away. She was raised among the intelligentsia and taught several languages, travelling widely in Europe, where she visited galleries with her adopted parents. At 19, she enrolled at the Art Academy in Karlsruhe in Germany, and then moved to Paris, where she studied at the Académie de la Palette.

In 1908 she painted Nu jaune, which hangs in the first room at the Tate retrospective (until 9 August). A woman lies on her side, in black knee-high stockings, eyes lowered; there’s something red, a bow or a flower, in her hair. The catalogue essay says the figure ‘fits into the iconographic context of the stereotypical images of prostitutes’ while being ‘stripped of any sensuality’. It’s true that the face is a geometric mask, the sharp yellow triangle of the nose descending into thick blue shadow, the long eyebrows extending to the edge of the hair. But it’s still an alluring picture, not for the figure but for the surfaces beyond it: the woman’s torso is propped up on a patterned cushion; she seems to be lying on a rug with flame-like motifs, flashes of bright green and orange that darkly mirror the shades of paint used for the body. Fabric matters already. Sonia Terk, as she then was, had clearly learned from Matisse (though she thought him ‘bourgeois’). But she was a diligent student and had learned from everyone: Nu jaune owes a great deal to Gauguin’s Tahitian figures, which she was very taken with after seeing them at Ambroise Vollard’s gallery on rue Lafitte; her thick black outlines were adopted from Derain; like everyone, she was swept away by the Douanier Rousseau. She persuaded Picasso to find out from Vollard, who knew Van Gogh’s art supplier, what kind of canvases Van Gogh had used, and how much turpentine, and how precisely he had constituted his whites. She needed to know how things were made.

She was helped in her endeavours by Wilhelm Uhde, a German gallerist with very good connections: he got her her first show, introduced her to everyone, and then married her. Uhde was gay and wanted to keep up appearances, Sonia needed to give her aunt and uncle a reason to allow her to stay in Paris. They took an apartment on the quai de la Tournelle, overlooking the Ile Saint-Louis; Uhde’s manservant and lover, Constant, lived with them too, but no one seemed to mind. They gave dinner parties – for Gertrude Stein and Alice Toklas, for Vlaminck, Braque and Derain. One night the unstoppably talkative Robert Delaunay came over with his mother, a countess: he was a young painter under the spell of Cézanne who had dropped out of school and done a stint as an apprentice set designer in Belleville. Sonia and Robert started to spend time together; Sonia got pregnant. She divorced Uhde and married Delaunay; everyone was delighted. When her son was born she made him a quilt for his crib. It hangs on the wall in the Tate show, a patchwork of coloured fabrics – all oblongs and triangles and sweeping lines connecting one shape to another. ‘When it was finished,’ she later said, ‘the arrangement of the pieces of material seemed to me to evoke Cubist conceptions.’

The quilt was responsible for a great deal that happened next. Not only was it sort of Cubist; it was also sort of Russian, in a folk art way; and she now had a style she could call her own. Or rather, she and Robert had a style: they called it simultané – a system by which, Robert explained, ‘simultaneous’ contrasting colours placed next to each other created a sense of motion and rhythm. It worked for paintings, and it worked for cushion covers too: while Robert painted, Sonia set about transforming their Saint-Germain apartment into a work of art, painting the walls white and filling it with rugs, lampshades and screens of her own design. She threw herself into city life; as well as holding regular salons, she got caught up in the tango craze that was sweeping Paris. Le Bal Bullier (1913) suggests a scene from the dance hall where she went many nights. The dancing figures, blocks of colour, are shapes that fold into one another and become part of the overall pattern. In a case opposite it in the Tate one of her ‘simultaneous’ dresses (also 1913) is displayed on a dressmaker’s dummy. It’s a riot of patchwork: fake fur, leather, velvet, purple, black, green, all stitched together in the form of a dress. It’s harlequinry gone mad. Sonia often wore it to the Bal Bullier and dancing in it was a form of performance art. She was part of the pattern too.

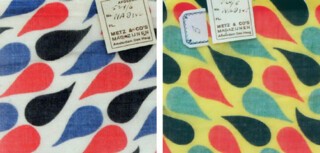

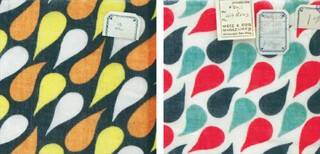

The Delaunays were holidaying in Spain when the war began and stayed there for the next seven years. In 1917, following the Bolshevik uprising, the Terk family property in Petrograd was confiscated: suddenly Sonia lost the thousand francs a month from her uncle that had kept their colourful life going. She gave up painting and concentrated on textile design, which gave her a chance to make money. In Madrid, with the help of her old friend Diaghilev, she opened Casa Sonia, a shop selling simultaneous clothes and accessories, furniture and fabrics. It did well with the city’s aristocrats, and soon there were branches in Bilbao, San Sebastian and Barcelona. By the time they were back in Paris with a new brand, Maison Delaunay, she was able to employ a team of Russian seamstresses and embroiderers. She met Joseph de Leeuw, the owner of the Amsterdam department store Metz & Co, and began designing for him and for Liberty. You can easily imagine some of the fabrics – Design 965, for example, with its red, blue and cream teardrop shapes on a bright blue background – on cushions in the Conran Shop today or, better still, in your own house. In one of the exhibition’s rooms, bright Marimekko-like fabrics rotate on giant moving panels. There’s a black and yellow striped parasol and matching clutch bag that would be nice if you had somewhere to put them, though the knitted bathing suit they’re displayed alongside is perhaps a little less now. There’s a pair of embroidered court shoes: dark blue zigzags, with brighter blue, green and white triangles, and silver leather straps to top it all off. They’re the most life-affirming shoes I’ve ever seen. A contemporary film shows Sonia and a series of models wearing some of her outfits. It’s all very glamorous and sophisticated.

She closed her fashion business in 1929 after the economic crash, and after Robert died in 1941, she put most of her energy into promoting his legacy as a painter. It wasn’t until the 1950s that she started painting again, abstract images that make use of geometric forms. Or nearly abstract. In Rhythme syncopé (1967) – all bisected circles and overlapping squares – a sinuous black form running down the left looks just like one of her scarves from 1924. She really didn’t see a difference between mediums: clothes, textiles and paintings were all part of the same canvas to her. In 1965, when Yves Saint Laurent introduced his Mondrian shift dress, Harper’s Bazaar called it ‘the dress of tomorrow’. It wasn’t, of course, it was a version of an idea Delaunay had had forty years before. And Delaunay herself was scornful. The year after she died in 1979, at the age of 94, Jardin des Modes quoted a remark she’d made to a friend about YSL: his dresses, she said, were ‘a form of society entertainment’, ‘a circus’. Her works, on the other hand, ‘were made for women, and all were constructed in relation to the body. They were not copies of paintings transposed onto women’s bodies.’ The point being that you have to think of these things simultaneously.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.