Modern art was born into a market economy, and by the early 20th century it could no longer ignore its commodity status. While some artists sought to escape this condition through abstraction, say, others worked to underscore it with the readymade, an everyday product they simply nominated as an artwork. In its first incarnation, with Dada, this device was taken to be critical of the cultural-economic system in which it was enmeshed, but by the time of Pop such negativity had all but drained away. ‘A new generation of Dadaists has emerged today,’ Richard Hamilton wrote in 1961, ‘but son of Dada is accepted.’ With Jeff Koons, the current maestro of the readymade, whose work is the subject of a retrospective at the Whitney in New York (until 19 October), acceptance has become affirmation, even celebration (his term). ‘I have always tried to create work,’ he has said, ‘which does not alienate any part of my audience.’

The child as an ideal of innocent vision is another old trope of modern art, and it too takes on a new twist with Koons, who aims to convey a youthful wonder at the object world around him. Here, however, innocence means less freedom from convention than delight in the commodity image, even identification with it, as he suggests in the account of a primal scene he gave in an interview with David Sylvester:

Childhood’s important to me, and it’s when I first came into contact with art. This happened when I was around four or five. One of the greatest pleasures I remember is looking at a cereal box. It’s a kind of sexual experience at that age because of the milk. You’ve been weaned off your mother, and you’re eating cereal with milk, and visually you can’t get tired of the box. I mean, you sit there, and you look at the front, and you look at the back. Then maybe the next day you pull out that box again, and you’re just still amazed by it; you never tire of the amazement. You know, all of life is like that or can be like that. It’s just about being able to find amazement in things.

This point of view – of the world seen by a boy precociously alert to the sexuality incited by consumerism – is one key to Koons, and it drives his refashioning of the readymade in terms of the child that commercial culture often takes us to be. As a result, his readymades have as much to do with display, advertising and publicity as with the commodity per se. (His father, Henry, was an interior decorator who owned a store in York, Pennsylvania, and even in his youth Koons was an avid salesman; he went on, briefly, to sell mutual funds and to trade commodities on Wall Street.)

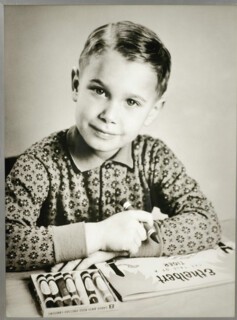

Koons broke through in the early 1980s with a series titled ‘The New’ consisting of store-bought vacuum cleaners and other pristine appliances; set on or placed inside fluorescent light boxes, each immaculate product glows with a godly aura. Among the ‘New Hoover Convertibles’ is The New Jeff Koons (1980), a self-portrait which, enlarged from a family photo of the artist-to-be not long after his fateful encounter with the cereal box, also radiates a special wellbeing, here the wellbeing of a middle-class boy circa 1960. Shirt buttoned up, hair neatly combed, young Jeff sits at a desk with a colouring book, a crayon poised in his chubby fingers, and smiles up at the camera (adult Jeff, too, is almost always beaming in photos). In his lexicon ‘The New’ implies perfection in the sense of pure as well as packaged, and The New Jeff Koons exudes both qualities. Although the family photo is obviously staged, so thoroughly does young Jeff inhabit the appointed role of budding artist that it seems absolutely authentic. Again, the mood is celebratory, and why not if your vision of life brooks neither death nor decay?

Koons is Panglossian in his artworks and statements alike, and – as with Warhol, who also ‘liked’ everything just as it is – this prompts the inevitable question: is he sincere or ironic or somehow both at once? It is difficult to call his bluff (again as with Warhol, you get stuck in his faux-naive language) or to catch him out (it’s been thirty years, and Koons is yet to step out of character). ‘I hope that my work has the truthfulness of Disney,’ he told Sylvester, and here as elsewhere it seems that Koons believes what he says and that his version of sincerity is the most sardonic thing ever. Yet when he adds, ‘I mean, in Disney you have complete optimism, but at the same time you have the Wicked Witch with the apple,’ you are given a useful insight into the workings of both impresarios.

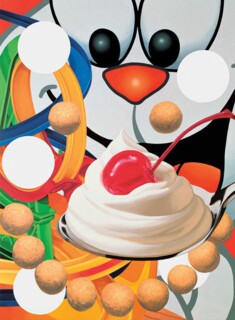

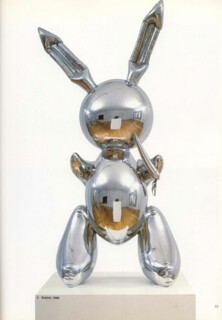

This poisoned apple, this witchy charm, is what Koons offers in his best work, and when the ambiguity isn’t there, the performance falls flat. Thus his paintings are mostly a computer-assisted updating of Pop and Surrealism, equal parts James Rosenquist and Salvador Dalí (his first love), and the sculptures that mash up pop-cultural figures like Elvis and Hulk are also usually overdone. So, too, Koons often fails to inflect the three categories that are his bread and butter – kitsch, porn and classical statuary – with much edginess or even oddity; their tautological structures (‘I know porn when I see it’) appear to resist his attempts. Some of his objects cast a spell nonetheless, especially early ones such as his Hoovers presented as fetishes and his basketballs submerged in tanks of water, in a state of ‘equilibrium’ (the title of this 1985 series) that Koons likens to that of a foetus in a womb as well as to a state of grace (is there a pro-life message here?). He is also able to fascinate with objects that are not at all, physically, what they appear to be imagistically, such as Rabbit (1986), a bunny cast in stainless steel and finished to the point where it looks exactly like the cheap plastic of the inflatable toy that is its model. This is a talismanic piece for Koons, for it confirmed his shift from the relatively simple device of the readymade to the very painstaking one of the facsimile. Here he adapts the unusual genre, ambiguously positioned between art and craft, of the trompe-l’oeil object (the pictorial version of such illusionism is familiar enough), exactly reproducing a tacky curio (such as a Bob Hope statuette) or an ephemeral trifle (a balloon animal) in an unexpected material like stainless steel. Koons thus renders the thing (which is already a multiple) a weird simulation of itself, at once faithful and distorted; and, paradoxically, this illusionism reveals a basic truth about the ontological status of countless objects in our world, where the opposition between original and copy or model and replica is completely undone.

With this illusionism, as Scott Rothkopf, the curator of the retrospective, points out, Koons turns the readymade on its head, transforming cheap nick-nacks into ultra-expensive luxuries. His ‘Celebration’ series (1994-2006) includes twenty large sculptures of cracked-open eggs, balloon figures, hanging hearts and diamond rings; cast in high-chromium stainless steel, coated with transparent colour and polished to a mirror shine, they are inspired by the gifts we exchange on such occasions as birthdays, Valentine’s Day and weddings. These deluxe outsize decorations might strike even jaded viewers with the ‘amazement’ the young Koons felt in front of his cereal box; certainly they are fit for a king – or an oligarch.

What is the point of this art? Koons claims he wants to relieve us of our shame, which is why he focuses on two subjects where humiliation runs deep – sex and class. ‘I was just trying to say that whatever you respond to is perfect, that your history and your own cultural background are perfect,’ he remarks of the tschotskes (like the Bob Hope statuette) reworked in his ‘Banality’ series (1988), in language not unlike that of a cult therapist who has drunk his own Kool-Aid. Yet here too his work is more effective when our shame – or our ambivalence at least – is triggered, not wished away. When Koons desexualises sex, as in the images worked up with his ex-wife, the Hungarian porn star and Italian politician Ilona Staller (aka La Cicciolina), in the ‘Made in Heaven’ series (1989-91), there is little charge. Yet when he sexualises ‘things that are normally not sexualised’, as he puts it, such as children, flowers and animals, an edgy unease is sometimes the result.

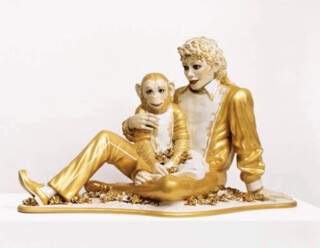

Consider the porcelain boy and girl of Naked (1988). Rather than an Edenic purity, these pre-pubescent twins evoke a nasty prurience; they also gaze into an abundant flower that looks as though it might hold a dark Bataillean secret about the true nature of sexual organs. Koons makes his animals even more polymorphously perverse (based on toys and curios, they are creepily semi-human to begin with). Take Rabbit again. The bunny is an infantile thing, but it is also an adult symbol of rampant sex, and this one is erect in all its bulbous parts; Koons refers to it as ‘The Great Masturbator’ after a 1929 painting by Dalí. Or take Balloon Dog (1994-2000), which at first appears as innocent as its birthday-party inspiration. ‘But at the same time,’ as Koons says, ‘it’s a Trojan horse. There are other things here that are inside: maybe the sexuality of the piece.’ And after a while it does begin to look like a poupée by Hans Bellmer reworked for a super-rich kid. Edgier still is the sexuality suggested in Bear and Policeman (1988), a polychromed wood piece that shows a big cartoonish bear in a childish striped shirt looking down on a boyish bobby (whose whistle the bear is about to blow), and in Michael Jackson and Bubbles (also 1988), a well known porcelain piece that shows the King of Pop cuddling with his pet chimp (Koons predicts a whitened Jackson here). The two sculptures point to an illicit love that crosses not only generations but also species, and Bear and Policeman implies a further joke about English pop culture (the juvenile bobby) being schooled by the bigger, badder American version (the papa bear).

‘My work’ is meant to ‘liberate people from judgment’, Koons told Sylvester: ‘I’ve always been aware of art’s discriminative powers, and I’ve always been really opposed to it.’ And Rothkopf feels that Koons has indeed ‘achieved a kind of democratic levelling of culture’. Yet as with sex, so with class: his work is more effective when it sharpens our sense of social difference and tweaks our guilt about bad taste. Thus in the bar accessories that Koons made over in stainless steel in his ‘Luxury and Degradation’ series (1986), his ice pail, travel bar and the Baccarat crystal set register class distinctions rather precisely. And in the kitschy curios of the ‘Banality’ series we are not released from judgment so much as invited to entertain a campy distance from lowbrow desires or even a snobbish contempt for them.

In a telling moment Koons tells Sylvester that his work is ‘conceptual’ in that it uses aesthetics as a ‘psychological tool’. And at the end of the conversation he makes an extraordinary remark:

What I’ve always loved about the Pop vocabulary is its generosity to the viewer. And I say ‘generosity to the viewer’ because people, everyday, are confronted by images, and confronted by products that are packaged. And it puts the individual under great stress to feel packaged themselves … And so I always desire … to be able to give a viewer a sense of themselves being packaged, to whatever level they’re looking for. Just to instil a sense of self-confidence, self-worth. That’s my interest in Pop.

This credo fits in well with the therapy culture long dominant in American society (the only good ego is a strong ego, one that can beat back any unhappy neurosis), but it also suits a neoliberal ideology that seeks to promote our ‘self-confidence’ and ‘self-worth’ as human capital – that is, as skill-sets we are compelled to develop as we shift from one precarious job to another. When the perfectly presented boy in The New Jeff Koons looks into the future, perhaps what he sees is us.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.