I wanted to go to Burning Man because I saw the huge festival in the Nevada desert as the epicentre of the three things that most interested me in 2013: sexual experimentation, psychedelic drugs and futurism. But everyone said Burning Man was over, that it was spoiled. The event, which requires those who attend to bring their own food, water and shelter and dispose of their own trash, was overrun with rich tech people who defied the festival’s precious tenet of radical self-reliance with their over-reliance on paid staff. Burning Man, which started in 1986 when twenty people burned an effigy on a beach, was turning into a dusty version of Davos. Old-timers lamented the rise of ‘plug and play’ culture. There were too many LEDs now, too many caravans, too many generators, tech executives, and too much electronic dance music. There were TED talks. There were technolibertarians. You couldn’t see the stars.

I would decide for myself. I rented a caravan with six other people, a group organised by a friend in San Francisco. If someone were to draw a portrait of the people who were ‘ruining Burning Man’ it would have looked like us. With one exception the six all worked in the tech industry. The exception was a corporate lawyer. None of us had been to the festival before. We paid a company from San Diego to drive our caravan to Nevada and get rid of our trash afterwards.

I ordered the items from the packing list online: dust goggles, sunscreen, sun hat, headlamp, light-emitting diodes, animal-print leggings. I arranged delivery of a bicycle. My friends would bring food and water from San Francisco. They all delayed their planning with the flexibility of people who don’t worry about money. They bought plane tickets at the last minute, and then changed their flights. One of them still hadn’t got a ticket two days before he was supposed to go. One of them ordered a bicycle from eBay Now and had it delivered to his office within an hour, like a taco. One ended up flying the hundred miles from Reno to Black Rock City in a chartered Cessna.

This year 68,000 people came. Fifteen years before there had been 15,000. The festival is organised in circles, like Dante’s Inferno. The circles, letters A through L, are intersected by minutes, like a clock. Most people stay at themed camps, which combine collective infrastructure – kitchen, sun showers, shade, water tanks – with individual dwellings. These range from high-end operations with a full catering service to groups of friends in tents. Some of the themes are creative: one camp, Animal Control, is dedicated to trapping and tagging festival attendees wearing animal costumes. Others serve coffee to the public every morning, or play only music by the Grateful Dead.

Because we were depending on some people from San Diego to provide us with a caravan and hadn’t set things up till the last minute, we were placed on the outermost circle, at L and 7.00, next to the guy who had driven 15 caravans up from San Diego. His name was Jesus. I was the first of my friends to arrive. He showed me various stowaway beds, then pressed a button to expand the width of the caravan. In the process, an open medicine cabinet door was ripped off its hinges. Its mirror shattered. ‘I’ll clean it up,’ Jesus said. I watched him scoop up piles of broken glass with his bare hands.

I biked out to the playa, the central area where things go on at night. I passed large structures circled by glowing people on bikes. I was lonely. I didn’t yet understand the place. I returned to the caravan, found it still empty, and went out again. I watched an animatronic octopus spit fire from its articulated metal limbs to the rhythm of electronic dance music. I climbed the spaceship with the effigy on top that gives the festival its name. I went back to the caravan.

My friends arrived after 3 a.m. I say ‘my friends’ but I only knew one of them, Ben, and I barely knew him. Earlier in the summer we had spent a week together in Portugal after getting together at a wedding. The last time I saw him had been at 7 a.m. in Lisbon, when he left to catch a plane to a bachelor party in Austin, Texas. Now we were reunited in the middle of the night in the middle of the Nevada desert. Other than sex we had nothing in common. ‘We have nothing in common!’ we would marvel.

He lived in San Francisco, worked in tech and made lots of money. He was always ‘slammed’ at work. He had subscribed to a DNA mapping service that predicts how you might die, the results of which are posted to an iPhone app, so that your iPhone knows how likely you are to get heart disease.

When the subject of the festival first came up we both talked about how we wanted to go, how we knew people made fun of it but that we were drawn to it. He said he saw it as a good ‘networking opportunity’, but we also saw it as something that was happening right now and only right now, and we were both interested in things specific to the present. Now he put on a reflective jumpsuit and a fedora. We ate some caramel-corn marijuana bought from a California medical dispensary, went out until dawn, then came back to the caravan and had sex, despite the other occupants.

The greeters at the gate had given us a guidebook; the lists of events read like mini prose poems in futurist jargon: ‘NEW TECH CITY SOCIAL INNOVATION FUTURES … Creative autonomous zones & cities of the future … resiliency, thrivability, open data, mixing genomes and biometrics with our passwords and cryptocurrencies. What’s your future look like? Social entrepreneurs and free culture makers, hack the system and mash the sectors.’ For someone interested in sexual experimentation, the possibilities for self-education here were endless: there were lectures on orgasmic meditation, ‘shamanic auto-asphyxiation’, ‘ecosexuality’, ‘femtheogens’, ‘tantra of our menses’, ‘sex drugs and electronic music’ and the opportunity to visit the orgy dome.

I went to a lecture on new research on the use of hallucinogens in treating illnesses. I listened to someone describe her research on ‘Transpersonal Phenomena Induced by Electronic Dance Music’. The weed made Ben excitable and inattentive.Next to his bed, a small landfill of plastic water bottles had accumulated. I wasn’t sure if he wanted to hang out with me, or share his lifehacked body with the naked free spirits of Burning Man. I wasn’t sure what I wanted. The second night, to give everyone space, I biked over to the outer playa, where it was silent, empty and very cold. I went to bed early.

The next day I woke up around 9 a.m. I went out alone and walked past a plywood booth painted yellow. Its sign advertised ‘Non-Monogamy Advice’. A rainbow flag blew taut in the wind, the words ‘Yes Please’ printed on it in white. Beneath that was a black flag with a skull and crossbones. Signs hung on the booth said the doctor was ‘curious’ and ‘available’, but I didn’t see anyone. I went closer to read the articles taped to the booth, which claimed humans hadn’t evolved to be monogamous.

A tall, sleepy-looking man with a shaved head walked up holding an enamelled metal cup of coffee. He was sunburned and blue-eyed and spoke with a Northern European accent. He sat down at the other side of the booth. I sat facing him. The sun beat down. ‘Would you like an umbrella?’ he asked. Two umbrellas were leaning against the booth. He opened a rainbow umbrella and I opened a black one and we looked at each other from beneath our umbrellas. I took off my sunglasses. ‘Do you have a question?’ he asked.

I didn’t. I told him that my last relationship had ended two years ago. I supposed that since then I’d been non-monogamous, in the sense of sometimes having sex with several different people within a specific period of time. As I said this both the idea of counting people and the idea of grouping them within a timeframe seemed arbitrary. This was just my life: I lived it and sometimes had sex with people. Sometimes I wanted to commit to people, or them to me, but in the past two years no such interests had fallen into alignment. I had started on this behaviour more or less by accident, still thinking that I would find someone I loved and begin a relationship. Now I sought out sex even when it would lead nowhere. I thought of it as an important way to connect with friends. I saw good sex and bad sex as equally valuable. But there were still some problems, I said. I still didn’t feel as free as I wanted to. Sometimes I couldn’t cross the barriers that keep people from expressing their desires. Rejection didn’t hurt any less, although it didn’t hurt more, and I knew better now how to work through it, mostly by having sex with other people. It still seemed tricky to get from point A to point B with total ease, despite all of the facilitators specifically designed for that purpose on the touch screen of my mobile. I asked the guru about jealousy. ‘Jealousy is something you have to feel,’ he said. ‘I don’t try to argue it away, or pretend it isn’t happening. I just sink into it.’

He was from the Netherlands. He had been in a polyamorous relationship that ended when he realised he and his girlfriend no longer loved each other. Sometimes it seemed like polyamory was just a slower, more humane way of breaking up with someone, and don’t most people, in most relationships, know from the start the way the relationship will end? Eventually I put on my sunglasses, closed my umbrella and stood up to continue walking. I wanted more moments like that, but the place was mostly deserted. It was early.

I walked past a library. I went in and sat down and started looking at the broadsheet daily newspaper that someone prints during the festival. A caption described people falling off a sculpture of a coyote. Across from me a man with dark hair and black glasses sat looking through a stack of comic books. We began to talk. Like me he lived in Brooklyn. It was also his first time here. He had just got a haircut at a salon theme camp. Since we were in the library we talked about books. We’d both read a book that describes what would happen if humanity suddenly disappeared: the way nature would reclaim the planet, the way our cities would decay, how long it would take the effects of global warming to be felt, how long plastic would remain. We talked about megafauna. He wondered how dinosaurs had overtaken them in the popular imagination. We talked about Narnia and Ursula Le Guin, an anarchist and a polyamorist. He told me that when she was a child, her family had sheltered the last Native American in California living outside modern culture, who had wandered one day from the forest into the parking lot of a grocery store. I asked if it was the man described by Lévi-Strauss in Tristes Tropiques. It was, he said.

He was going to have a steam bath. Did I want to come? His name was Jean. I asked if his parents were French. No, he said. Canadian? I asked. Egyptian, he said. He mentioned that the last time he had gone into the steam bath he had been coming down from acid. At this point he admitted it was not his first time here, but his fifth. He would tell people it was his first so they would be nicer to him. This baffled me. I asked him how old he was. He didn’t want to say. ‘I’m 32,’ I volunteered. ‘I’m 33,’ he said.

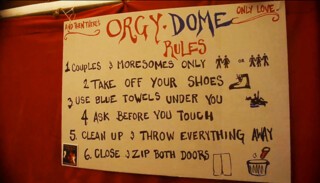

We arrived at the steam bath just after noon. We stripped naked and stood in line. The sun felt good. We were given umbrellas to stand under. The steam bath was in a hexayurt. The atmosphere was collegial, with people singing songs and spraying one another with a hose. We met a guy from Mongolia. We washed off the dust with peppermint soap. Afterwards, the desert air felt cool. We dried in the sun, then put our clothes on again. We decided next to go to the orgy dome, something one could only do as part of a ‘couple or moresome’. First we had to get my bike.

To get my bike I had to tell Ben something about where I was going. I introduced him to Jean. I figured Ben had his own conquests ahead of him. His tan had deepened and he wore only a small pair of shiny golden shorts. ‘Feel the jealousy,’ I told myself.

Jean and I hadn’t discussed our purpose in going to the orgy dome. We had, after all, just met. The orgy dome was said to be air-conditioned, but it was barely air-conditioned. We were handed a bag with condoms, lube, wet wipes, mint lifesavers and instructions for how to dispose of our materials afterwards. We entered the dome. I was disappointed that there wasn’t much of an orgy. In fact it was all heterosexual couples having sex with each other. Jean and I sat on a couch and watched. We felt strange. It was clear that we either do something or leave.

‘Should we have sex?’ I asked.

‘Yes …’ he said. ‘Do you want to?’

‘Yes,’ I said.

‘Are you sure?’ he said.

‘Yes,’ I said. The woman who greeted us at the door had advised us to express loud, enthusiastic consent.

When we left the dome, we walked to a nearby shade structure where sitar music was playing. A woman who said she was from Columbus, Ohio, came by with a jug of iced coffee and offered us some. I accepted. Jean sniffed it and looked tempted but said no. He tried to be entirely straight edge, he said. The only time he allowed himself drugs was at Burning Man. He was an anarchist, and tried to live as close to his political principles as possible, which meant not partaking of things that come from thousands of miles away, like coffee. He also forbade himself to watch porn, didn’t have a mobile phone, and made a point of trying to get by on as little paid employment as possible, as a sort of protest. We had this final trait in common.

I asked him, why not watch porn? He said he thought it messed up his mind. We talked about the differences between male and female sexuality. I said I thought men and women wanted sex equally, but maybe the female body has a hard time having sex repeatedly. I was thinking of my own body, which felt tired. ‘It’s frustrating, because I could have sex three more times today, if my body could take it,’ I said.

‘I could have sex five more times,’ he said.

We left the sitar tent, got on our bicycles, and cycled towards the playa. We wanted to look at a sculptural re-creation of the Mir space station. We found it and went inside. One of the Russians who’d built it was dismantling the lights. The space station was going to be set on fire later that night. ‘First time in America. First time at Burning Man,’ he said with a thick accent. We asked if he would take the festival back to Russia. ‘There is no place like this in Russia,’ he said. ‘There would be rain.’ Jean suggested some sort of dry Eastern steppe? The Russian ignored him.

Jean and I left the space station, cycling towards the Temple of Whollyness, where some friends of friends of his were due to be married at 4.45. We passed a Mayan pyramid topped with the giant thumbs up icon of a Facebook ‘like’, which would later be set on fire. Jean told me about the first time he had come to the festival, in 1999. None of this existed yet – Facebook ‘likes’, cell phone cameras, Russian delegations. It was smaller then, just serious environmental activist types with a leave-no-trace ethic. But it was the same, he said. Anybody who said it had changed was wrong. It was just bigger now, and as any society grows it experiences the same problems, the same stratification.

The temple was also a pyramid. Inside, objects connected with various religious traditions had been removed from their history, thrown together in a sort of panspiritual admixture of, well, whollyness. A Buddhist anvil dominated the centre of the room, and several hundred people sat around it on the floor in silent meditation. Gongs on the walls struck at automatic intervals. We couldn’t find the wedding we were looking for, but another couple were getting married, and we cheered them. Afterwards, sitting together in the sun and dust, we assembled a hexagonal plywood structure that joined other hexagonal structures in a sort of plywood molecule. We were supposed to write something on it, but we didn’t write anything. We watched as it was placed with the others and then we left. On Sunday it would be set on fire.

The day was fading. ‘This is normally when I go back to take a nap, but this day,’ Jean said. ‘I don’t know what to do about this day.’ I knew what he meant. I had never had a day like this in my life. I had never become so close to someone so quickly. We visited a geodesic dome. We went to a chapel containing an organ that Jean wanted to play before it was set on fire. Inside, more people were getting married. He picked out ‘Here Comes the Bride’ on the organ and we cheered the happy couple. We shared his dinner, a grilled cheese sandwich with some tomato soup. We made plans to meet at noon the next day. I didn’t keep the rendezvous.

Instead I went back to my caravan and took a synthetic hallucinogen on blotter paper called 2CB. (Later, a friend suggested it was a chemical in the family of drugs known as NBOMes, which the administrators of the website Erowid call ‘the defining psychedelics of 2013’. They were invented in 2003 by a PhD student in Berlin and first hit the market in 2010. Ours had been ordered from the website Silk Road and paid for with bitcoin internet currency.) It was like acid but without acid’s dark side. It was acid re-engineered to be joyful. We each put half a hit under our lips and went out into the night, the chemicals leaching from the paper as the Mir space station was set on fire, the wedding chapel set on fire, the Facebook ‘like’ set on fire. We wandered through the LED-infused landscape, its colour palette that of the movie Tron, a vision of the future that had now become the future, a future filled with electronic dance music.

The drug hit us when we were playing beneath an art installation of rushing purple lights. We ran and danced in the lights, laughing and gasping. We boarded mutant vehicles. One shaped like a giant terrapin, one a post-apocalyptic pirate ship called the Thunder Gumbo. We danced on top of the vehicles. Below us the burners on bicycles orbited like phosphorescent deep sea crustaceans. The memory of my day kept coming back to me. I kept thinking I was seeing people having sex, then realised I had just seen a pile-up bike crash. I kept thinking I had met the people around me before. We put more paper under our lips.

I began to see conspiracy. A mutant vehicle pulled up alongside us. On top I could see several people in their fifties and sixties. I saw them as aristocrats. They seemed to be wearing Aztec mohawks and Louis XVI-style powdered wigs. Their vehicle, which was shaped like a rainbow-coloured angler, was called the Disco Fish, and was self-piloted by programmable GPS. Its scales were the colours of the Google logo. I saw the Disco Fish as a secret plot by Google to defy Burning Man’s anti-corporate ethos with its self-driven cars, the project overseen by the executives on the second tier. My suspicions seemed confirmed when one of their number began discussing a show at the Guggenheim with one of my friends.

Still, we rode on the Disco Fish. We danced. We stayed up until sunrise. We slowly made our way back to the caravan. One of our number had just left the company he had founded with a fortune. He no longer had to work, ever. He told us about all the things he’d thought about this year, when a job that once seemed magical had transformed into a grind. The day before he left for Burning Man, he was paid to leave. While we sat there, outside the caravan, Ben returned. He wore blue leggings printed with the characters from The Little Mermaid and a white fur jacket. Someone had painted his face. He was exuberant. He’d biked to the edge of the playa and watched the sun rise. I hugged him. I was so happy to see him. The corporate lawyer arrived, wearing Superman boxers and a bikini. We were all experiencing our own private revelations. Most of us were still tripping. Nobody wanted to sleep.

No wonder people hate Burning Man, I thought, when I pictured it as a cynic might: rich people on vacation breaking rules that everyone else would be made to suffer for not obeying. Many of these people would go back to their lives and back to work on the great farces of our age. They wouldn’t argue for the decriminalisation of the drugs they had used; they wouldn’t want anyone to know about their time in the orgy dome. That they had cheered at the funeral pyre of a Facebook ‘like’ wouldn’t play well on Tuesday in the cafeteria at Facebook. The people who accumulated the surplus value of the world’s photographs, ‘life events’ and ex-boyfriend obsessions were now celebrating their freedom from the web they’d entangled all of us in, the freedom to exist without the internet. Plus all this crap – the polyester fur legwarmers and plastic water bottles and disposable batteries – this garbage made from harvested hydrocarbons that will never disappear.

To protest against these things in everyday life carried a huge social cost – one that only people like Jean were grimly willing to bear – and maybe that’s what the old burners disliked about the new ones: the new ones upheld the idea of autonomous zones. The $400 ticket price was as much about the right to leave what happened at the festival behind as it was to enter in the first place. Still, I’d been able to do things here that I’d wanted to do for a long time, that I never could have done at home. And if this place felt right, if it had expanded so much over the years because to so many people it felt like ‘home’, it had something to do with the inadequacy of the old ways that governed our lives in our real homes, where we felt lonely, isolated and unable to form the connections we wanted.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.