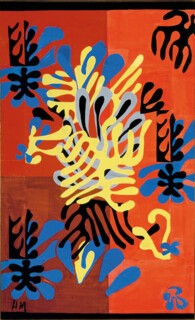

Crowds gather at the heart of Henri Matisse: The Cut-Outs, drawn to an artless home movie showing the master at work. He looks, and was, extremely unwell. Not even a rakish straw hat, part cowboy part Maurice Chevalier, can divest the scene of its pathos. There is a spot of time in the movie, after Matisse has finished his fierce fast cutting of the usual vegetable-flower-seaweed-jellyfish shapes (the ones he works on here are not unlike the clusters of yellow in the centre of Mimosa), when the speed suddenly slackens and the old man holds the limp paper in his hands as if reluctant to let go. He fusses with it a little, prodding and twisting the fronds in space, maybe trying to thread the shapes together, buckling them, letting them be carried for a second as they might be by a breeze or current. He seems to be waiting for the cut-outs to occupy space – to make space. Art for him is the moment at which, to quote a remark he made about Snail, one becomes ‘aware of an unfolding’. ‘At this time of year,’ he wrote to a friend, ‘I always see the dried leaves on your table, catching fire as they pass under your fingers from death to life.’

I thought, looking at the film sequence, that I could hear the paper shapes rustle. And the word – the imagined sound – sent me back to a wonderful essay by Roland Barthes called ‘The Rustle of Language’, and especially to its last two sentences:

I imagine myself today something like the ancient Greek as Hegel describes him: he interrogated, Hegel says, passionately, uninterruptedly, the rustle of branches, of springs, of winds, in short, the shudder of Nature, in order to perceive in it the design of an intelligence. And I – it is the shudder of meaning I interrogate, listening to the rustle of language, that language which for me, modern man, is my Nature.

Was Matisse at the end of his life the Greek or the modern? It is the question posed by this extraordinary show, and one in which the whole meaning and fate of ‘modern’ art is, triumphantly and sometimes painfully, at stake. Only a gathering of the evidence as comprehensive and beautifully staged as the one at Tate can give the question back its true dignity. And a proper answer, as Barthes tries to signal, can only be Hegelian in the strong sense. (That is, it should learn to wait for the seemingly contrary terms of a civilisation to reverse themselves.) Nature for the Greek, to use Barthes’s paraphrase of the philosopher, is, however far back in the record we go, always ‘shuddering’, and this intimation of uncanniness or distress in the object points to the fact that in the strange activity called sculpture, by reason of the sheer relentlessness of the Greek’s interrogation, Nature is already being asked – prodded and cut and twisted – to divulge a design, an intelligibility. Heraclitus is as modern as they come. The word ‘shudder’ reminds me of Fénéon’s great, cruel characterisation of Monet: that in practice the painter could only hang onto his dream of delighted subservience to eyesight, and make art out of the dream, by ‘making Nature grimace’. Matisse, who admired Monet greatly, thought constantly about the contrast between a painting devoted to pleasure and the agony involved in its production:

A man who makes pictures like the one we were looking at [he is writing to his son about Rouault’s The Manager and a Circus Girl, but no doubt also about himself] is an unhappy creature, tormented day and night. He relieves himself of his passion in his pictures, but also in spite of himself on the people round him. That is what normal people never understand. They want to enjoy the artist’s products – as one might enjoy the milk of a cow – but they can’t put up with the inconvenience, the mud and the flies.

Matisse too, with part of his mind, was tired of his turmoil. Painting was agitation. He said to more than one admirer late in life – no doubt intending to frighten, but still, I think, essentially telling the truth – that in order to begin painting at all he needed to feel the urge to strangle someone, or lance an abscess in his psyche. There ought to be a better way. ‘Paintings seem to be finished for me now’: he is writing in 1945 to his daughter Marguerite, who was recovering at the time from the horror visited on her in a Gestapo prison at Rennes. ‘I’m for decoration – there I give everything I can – I put into it all the acquisitions of my life. In pictures I can only go back over the same ground.’

Painting versus decoration. The undialectical answer to the question deriving from Barthes seems close. Painting, in Matisse’s case, had always equalled Nature. Certainly confronting Nature – passing it under his fingers – had proved to be delight as much as interrogation: a rustling and smoothing of things into the skein of colour that was painting, so he believed, and that painting had to fight continually to keep in being, up front. But doing so was inseparable from the murderous urge, the mud and flies, the grimace, the exacerbation – ‘the accomplishment of an extremist in an exercise’. ‘He took in front of nature,’ as an early critic had it of Cézanne, ‘the attitude of a question mark.’ Decoration might be a way out. Decoration, surely, would be ambience not ethos. It would provide a surrounding, not a model of the world’s design. It was a mode that expected, and in a sense welcomed, inattentiveness. (The rooms at Tate are friendly to it.) It would be, with its fabulous battery of primitive techniques – saturated high-key colour, repetition, redundancy, vegetable sign-language, evenness enlivened by syncopated quirks of brightness – a ‘sensation delivery system’. (Like the ‘nicotine delivery systems’ that tobacco CEOs once discussed in the privacy of the boardroom.)

Decoration, to sum up, seems regularly to offer itself within modernism as an alternative to art’s too high claims. But where the alternative leads – into what kind of accommodation with the culture industry – is never clear. I believe Matisse was right when he told his daughter that he had put into his late work ‘all the acquisitions of [his] life’, and that his skills as an artist would be sharpened by being put in the service of a new, more modest and realistic relation to the viewer. But he knew he was walking a tightrope. The best of the late murals – The Parakeet and the Mermaid from 1952, the grey Oceanias of 1946 – are remarkable for their unforced, drifting quality, the small shapes in them like knots and flutters in a vast empty field. The worst choke the field with optical buzz. The sustained unseriousness of Matisse’s brush with religion at this time, which served him so well as an artist, always threatens to collapse in the cut-outs into ritzy nostalgia for the South Seas: The Lagoon, Creole Dancer, The Negress, Women with Monkeys. Naivety – which Matisse inherited from the 19th century as a prime aesthetic value – is shadowed by simple-mindedness, as much a stage prop as the movie’s straw hat. In an exchange with Picasso about the Chapel of the Rosary in Vence, a commission that Matisse worked on from 1948 to 1951 (‘Why not a brothel, Matisse?’ ‘Because nobody asked me, Picasso’), it isn’t the smug facetiousness of Picasso’s Party Line question that matters, but rather the suspicion that Matisse’s answer may be, though he hardly knows it, the whole truth. Decoration without somewhere to decorate – applied art without a realm of pleasure or praxis to apply to – such is modernism’s ‘Why not?’

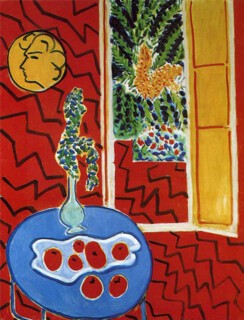

The problem that follows for the critic is not to decide whether Matisse’s cut-outs succeed, much of the time, in shrugging off these limitations of social purpose or available theme – only a killjoy or an iconographer could resist the splendour on the walls – but to speak rationally about how it was done. In many ways the most useful piece of writing about late Matisse remains an article called ‘Something Else’ published in Henri Matisse: Paper Cut-Outs almost forty years ago by the poet and essayist Dominique Fourcade. It is that rare beast in the art world, a catalogue essay of high seriousness that entertains real doubts about the quality of its objects. Naturally this means that it has been shuffled off subsequently into art-historical limbo (I can’t see that it gets a mention in Tate’s book to accompany the current show), but its arguments – coming from a writer with deep knowledge of Matisse’s art and life – seem to me worth revisiting. Fourcade begins by refusing to be impressed by the phrases from books and interviews invariably brought on to define the cut-outs’ originality. ‘Cutting straight into colour reminds me of the direct carving of the sculptor,’ Matisse said in Jazz. ‘I arrived at the cut-outs,’ he wrote to his protector Father Couturier, ‘in order to link drawing and colour in a single movement.’ But how is any of this new for Matisse? Hadn’t his painting ever since 1905 been an attempt to link drawing and colour in a single movement; that is, to make colour appear (it must be a matter of appearance, of contrivance, but if the spell works the result will be utterly convincing) to divulge its shape and extent, its internal spatiality, its proximity and distance? There is an oil painting at Tate which epitomises the previous colour regime. Red Interior: Still Life on a Blue Table is one of a cluster of works from 1947-48 that said farewell, so it turned out, to the set of objects – the intimate and agitated small world – around which Matisse’s painting had been oriented for half a century. (‘Window’, ‘table’, ‘glimpse of garden’ and ‘interior’ are tropes that the cut-outs then largely abandon.) It is very hard to pin down what makes Red Interior so beautiful and hard to bear. Partly it has to do with the zigzags of black on red being like a child’s sign-language for electric shock, or a strip cartoon’s for a punch to the head. I don’t want the head on the wall (a plaster of a long-ago lover) to be Marguerite’s in the cell at Rennes, but the idea won’t entirely go away. The dreadful, irresistible still life of apples in the foreground is like a malignancy under the microscope. The room and the movement into the garden are not torn apart by these jags of energy and absurdity – the space made by the red is finally one of shelter, even of calm – but everything is, and has to be, pushed almost to breaking point. ‘The inconvenience, the mud and the flies.’ Above all – this, I think, is what Fourcade cannot let go of – it is the unmitigated colour of Red Interior, aggravated and grimacing, which insists in Matisse, in painting after painting, that none of us has a ‘given’ place to be ourself any more, and that only painting can make one. The room turns towards us. The red is extruded as much as spread out. Whether it includes the viewer or means to hurl him into the outer darkness is undecidable. Whether the black zigzags are terrible or just jazzy, likewise. ‘Rustling’ doesn’t seem the right word.

Whatever else this painting may be, it is not a sensation delivery system. It knows that sensations belong to – or alas have been detached from – particular human occasions, ways of being, forms of life. But the exacerbation of colour in Matisse speaks, dialectically, to the lack of particularity that makes us ‘modern’. (This to and fro of contraries is dealt with powerfully in a new book by Todd Cronan, Against Affective Formalism: Matisse, Bergson, Modernism.) Colour, for Matisse – pure sensation, the stuff of the senses – will make, will be, a form of life. And at the same time it will enact the extremity – the uncanniness – of the wish.

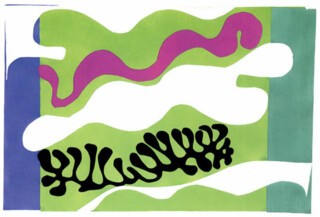

Locked inside this marvellous echo chamber (torture garden), what painter would not dream of a way out? ‘Luxe, calme et volupté’. Matisse had spent a lifetime coquetting with the Baudelairean catchphrase – and with the flies buzzing round Baudelaire’s ‘Une Charogne’. Fourcade, understandably, ends up preferring among the cut-outs those few that seem to him still pictures by Matisse, still struggling to make colour generate and palliate a dislocated world. Snail and Memory of Oceania, we may agree, are moments of high achievement in Matisse’s late style, and essentially, whatever the artist said to the contrary, they are still paintings done with gouache-soaked paper – great unstable arrangements of dabs, blocks of pigment, traces of previous drawn ideas, colour quadrilaterals like blown-up brushmarks by Cézanne. Snail’s slow whirlpool is painting incarnate. The edges of its cut-outs are most often torn as opposed to scissored, as if the artist had not been able to resist the recollection of art’s handmade-ness. Any viewer of Snail is ‘aware of an unfolding’. Nature – the forms made by stubborn life, armoured against predators, antennae waving, soft suckers feeling for placement – is still the matrix.

Fourcade’s concern about the late style (again, I should stress that he is eloquent about exceptions, local triumphs, the intrinsic difficulty of the quest) is essentially this:

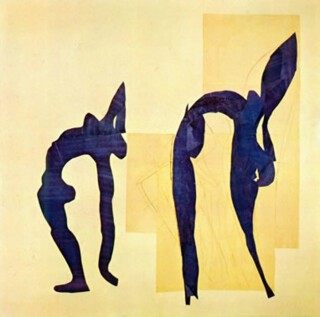

The cut-out forms never became integrated into [the unpainted white of Matisse’s ground]; the graft would not take. For the forms could never rid themselves of their built-in defect – namely, a contour which was so clearly defined, an edge so bluntly cut, that it turned the form back on itself, isolated it, deprived it of any communication with the surrounding space – trapped it, fatally.

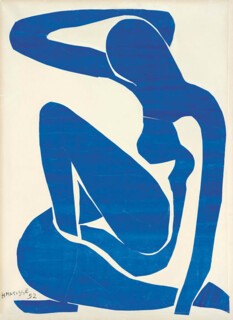

As commentary on Acrobats or The Thousand and One Nights, this seems fair. Matisse himself saw the problem. The four tour-de-force Blue Nudes from 1952 show him fighting, scissors in one hand, charcoal in the other, to fold or force the cut silhouettes into the invading white surround. That same summer he took the blue nude idea and stretched it around the four walls of his hotel room (the resulting 54-foot Swimming Pool, which belongs to MoMA, will presumably be hung in New York): the white ground becomes an unstoppable wind tunnel, pushing the fish and weeds and desperate bathers to the side of its Mallarmé blank. Snail, a few months later, with its uncharacteristic (for Matisse) foursquare format, seems deliberately a return to framed space and Cubist interleaving.

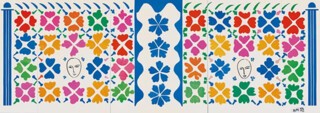

Rationally, then – and I suppose emotionally – I am on Fourcade’s side. Snail is my masterpiece. But reason and emotion don’t always have the last word in aesthetics. The cut-out at Tate which I find will not leave me in memory, though part of me would like to expunge it, is the enormous Large Decoration with Masks from 1953. It is a preposterous, merciless, spellbinding thing – with all the button-holing fake cheeriness of a roll of wrapping paper. (Snail and Memory of Oceania seem at one point to have been envisaged as Large Decoration’s side-wings.) Standing in front of it at Tate a remark of Willem de Kooning’s came to mind. The painter was being asked about his abstract pictures from the late 1950s, and suddenly he fell to talking about the landscaping of the new parkways on Long Island. Maybe the abstracts came from them. ‘They are really not very pretty, the big embankments and the shoulders of the roads and the curves are flawless – the lawning of it, the grass. This I don’t particularly like or dislike, but I wholly approve of it.’ I turn back to Large Decoration with Masks and want to say, with and against de Kooning – as by and large I find myself saying of even the strongest attempts within modernism at a new high ‘decorative’ – that I wholly disapprove of Matisse’s ingredients, but can’t stop liking and disliking the result. It lives on in me, the muzak. It stares me down. Its emoticons are full of what happens next in art – Warhol’s wallpaper, etc – but they resist it, idiotically. Branches and winds still rustle. That there is an invocation of Greece in Large Decoration – reminiscence of wall paintings from Akrotiri, a play of masks, columns, acanthus leaf – only makes the mixture more unforgivable and moving.

‘I have found three reproductions of Giotto in Padua,’ Matisse wrote to his friend Bonnard in 1946, ‘and am sending them to you. Giotto is for me the summit of my desires, but the route which leads towards an equivalent, in our epoch, is too long, too difficult [his word is importante] for a single lifetime.’ It is a letter from one ill old man to another – Matisse was 76 when he wrote it, Bonnard 78 with only months to live. But the sentences are characteristic of Matisse’s humility in the face of his predecessors, as well as of his realism with respect to the present. I hope it would please him to be told that in Snail – in the step by step unfolding of the cut-out shapes into a gold infinity round the edge – there lives on the tension of temple and empty sky to be found in Giotto’s Expulsion of Joachim.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.