The German painter Jörg Immendorff died in 2007, at the age of 61, after a long period suffering from motor neurone disease. His reputation had been tarnished by a scandal a few years earlier involving cocaine and prostitutes, but by this stage his artistic career had in any case already begun to falter; his late works never quite captured the success of his Café Deutschland series made around the turn of the 1980s, or the intense political works made after studying with Joseph Beuys at the Academy in Düsseldorf in the 1960s.

An exhibition at the Ashmolean, Joseph Beuys and Jörg Immendorff: Art Belongs to the People! (until 31 August) selected by Norman Rosenthal from the Hall Art Foundation in Vermont, shows how Immendorff remained in artistic dialogue with his former teacher throughout his life. For his students Beuys was a model of the total commitment, asceticism and seriousness required to be a true artist, down to the clothes you wore. Hanging high on the wall, Beuys’s Felt Suit (1970) is a righteously uncomfortable symbol of this commitment; ‘Ich kenne kein Weekend’ (‘I know no weekend’), as one of his titles has it, stamped on the front of a copy of Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason. Immendorff’s dialogue with Beuys can be traced back to his student days, but his uncompromising and directly political position meant that their paths soon diverged. For a time Immendorff made paintings and actions under the title ‘Lidl’, chosen for its Dadaistic, infantile sound. For these he often used the perplexing image of a fat, ill-looking baby, somehow an emblem of innocence and international understanding, but looking more like a remnant from a Terry Gilliam animation.

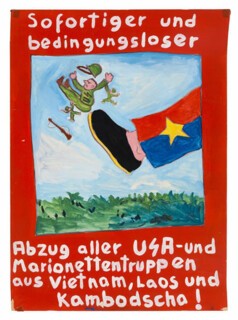

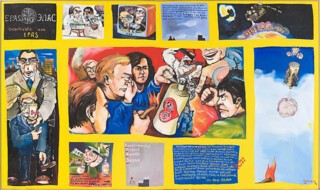

Around 1970, Immendorff severed his links with Beuysian mysticism entirely and adopted Maoism as his guiding ideology. He began making crudely propagandistic paintings, artful as political posters, but artless as art. A crudely painted image of a foot kicking soldiers into the air calls for the ‘Immediate and unconditional withdrawal of all US and puppet troops from Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia!’ Another work tells the story of EPAS, the joint Apollo-Soyuz flight of 1975, symbolic of the new Soviet-American post-Space Race and post-Vietnam détente. It shows a group of students attacking a canister of the perfume created by Revlon to commemorate the space flight, decorated with caricatures of Gerald Ford and Leonid Brezhnev. Like votive paintings in their naivety, Immendorff’s Maoist works were rejected when he offered them to the German Communist Party, and did just as badly when exhibited at the Michael Werner Gallery. Of the few that were sold, most were bought by the painter Georg Baselitz, not noted for his Maoist sympathies. A number of the works in the Ashmolean were once in Baselitz’s collection of work by his contemporaries, which was bought by Andrew Hall, the Anglo-American oil trader and collector, along with the castle where Baselitz lived and worked, at Derneburg, near Hildesheim.

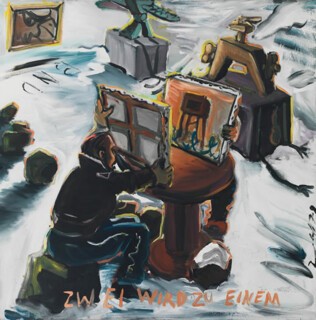

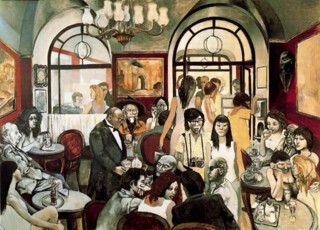

The Café Deutschland paintings, which Immendorff began making in 1977, were a turn away from direct politics to a type of weighty symbolism more in keeping with Beuys’s example. It was also a return to national political questions, against the backdrop of Willi Brandt’s Ostpolitik and the crisis of German terrorism – the ‘German Autumn’ – of that year. Immendorff was directly inspired by Renato Guttuso’s painting Caffè Greco, which shows an imaginary convocation of artists and writers; Immendorff’s equivalent is a hectic stage crammed with symbols of the division of Germany, dominated by the two central figures of Immendorff and the East German dissident artist A.R. Penck. The two met thanks to the gallerist Michael Werner, first in Berlin, then in Dresden, with the intention of some kind of border-busting collaboration, but the project dwindled when it turned out they had little to say to each other. Immendorff’s aim had been to persuade Penck to make art in the service of Stalin and Mao, but found that he was more interested in talking about science fiction and making paintings with prehistoric-looking stick figures. The Café Deutschland paintings, as well as a series of smaller works, such as Zwei wird zu einem (‘Two will be one’, 1979) showing the two artists confronting one another with their paintings, are undoubtedly Immendorff’s best works, and are among the most powerful artistic responses to the political division of Germany.

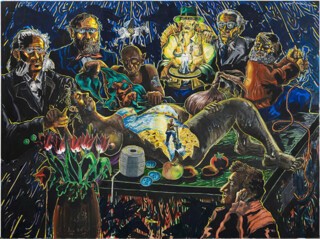

Immendorff’s acceptance in 1990 of a commission to design sets for a production of Stravinsky’s The Rake’s Progress in Salzburg surprised many who had seen him as a radical political artist, unwilling and unable to compromise. But the subject of the opera suited him better than anybody could have imagined. The set designs were the starting point for a long series of works based on themes from Hogarth, which included some wonderful late flourishes, role-playing (many are self-portraits) and memorable images. The florid iconography and symbolism of the Café Deutschland series spills over into the late works, but without the political imperative the vitality somehow dwindles. One of the most striking paintings in the Ashmolean display, Gyntiana – Geburt Zwiebelmann (‘Gyntiana – Birth of Onionman’), comes from another series, made around the same time, in which Immendorff adopts the persona of Peer Gynt. It takes the onion-peeling episode from Ibsen’s drama as the starting point for an esoteric meditation on the layers of German history, and artistic rebirth: Immendorff as Peer Gynt in a radiant landscape, revealed within the body of a prostrate woman, presumably Ibsen’s Solveig, surrounded by a small group of figures including Marx and Engels, Penck and Heinrich Heine. The obscure allegory of these later works (and also a lacklustre official portrait of the German chancellor Gerhard Schröder, a friend of the artist), suggests the failure of his attempt to create art as a direct tool of political struggle. With his sucked-in cheeks and trademark fedora, Beuys watches over Immendorff’s Gyntian reincarnation, holding a priestly candle.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.