Common sense in British politics tends to be aligned with the wisdom of party managers: that the electorate abhors uncertainty, and is incapable of understanding either internal party divisions or Continental-style coalitions. Only very occasionally, when the whips are thwarted by force of circumstance, do the voters – and indeed a frustrated cadre of pragmatic and independent-minded politicians – escape the iron cage of partisan constraint. In early 1974 Britain seemed divided and ungovernable, with Ted Heath’s Conservative government blown off course by the miners’ strike. In the February election the voters returned an uncertain decision: Harold Wilson’s Labour Party took 301 seats on 11.7 million votes, Heath’s Tories got 297 seats on 11.9 million votes, and the Liberals led by Jeremy Thorpe found that their six million votes translated into 14 seats. The Liberals’ mini-revival suggested a solution to Heath’s predicament, and led him to enter into negotiations with Thorpe. The discussions failed, and Wilson took office at the head of a precarious single-party minority government, which seemed unlikely to endure. One electoral campaign seeped into the next, and in the high summer of 1974 holidaymakers were treated to the surreal sight of Thorpe’s tour of South-West England’s beaches in a hovercraft, from whose running board, wearing a trilby and a three-piece suit, he would address the trunked and bikinied masses.

In the election of October 1974, Wilson got a bare majority, with 319 seats, but still lacked a clear mandate. Yet the country, it turned out, was less divided than it appeared. In 1975 there was a referendum on continuing membership of the Common Market (as we then called the European Economic Community). Wilson’s cabinet was split, with seven out of 23 cabinet ministers opposed to the terms – or indeed the principle – of British membership. In an unprecedented suspension of collective responsibility, Wilson allowed members of his government to participate on both sides of the debate. The cross-party Britain in Europe campaign was led by Roy Jenkins, then Labour home secretary, and supported by moderate consensus Tories such as Whitelaw and Maudling, the former Liberal leader Jo Grimond and middle-of-the-road Labour politicians like Cledwyn Hughes. On the other side of the argument were the bogeymen of British politics – from Enoch Powell, who was by then, scarier still, an Ulster Unionist, to Tony Benn and Michael Foot. With a sly coyness that sits oddly with her later reputation, the newly elected leader of the Conservative Party, Margaret Thatcher, operated, like Wilson, on the sidelines of the Yes campaign. The result, in a notionally divided country, was a resounding 67 per cent majority in favour of continued EEC membership. Whitelaw confessed in his memoirs that he had rather enjoyed working under Jenkins’s leadership for the Britain in Europe campaign. More significantly, the British public – notwithstanding the myths propagated by party zealots – seems to have had little difficulty with pragmatic Labour, Tory and Liberal politicians working together towards a common purpose. The laity has largely been spared subsequent opportunities to endorse cross-party co-operation.

The pejorative associations of the term ‘coalition’ are deep-rooted in British politics. The short-lived Fox-North coalition of 1783 became a byword for low cynicism and a willingness to seize power at whatever cost. According to George III, it was ‘the most daring and unprincipled faction that the annals of the kingdom ever produced’. Military defeat in the American War of Independence had wrecked Lord North’s long-running administration (1770-82) and a new ministry was formed out of North’s various critics, bringing together the Rockinghamites (nominally headed by the Marquess of Rockingham, but whose effective leader was Charles James Fox) and the followers of Lord Shelburne. This ministry was riddled with dispute, and on Rockingham’s death in the summer of 1782 the Foxites abandoned Shelburne’s new government, which itself imploded in the spring of 1783.

As in 2010, when the Cameron-Clegg coalition was formed, it was the arithmetic in the House of Commons that largely dictated the options available. In 1783, Fox had 90 followers, Lord North 120 and Lord Shelburne 140, with a walk-on cast of unaligned backwoodsmen among the rest of the 558 MPs in the House. In addition, the bruises acquired in the jostling between Shelburnites and Foxites remained fresh and sore, while Fox’s former criticisms of North’s policy towards the Americans, whose independence had been conceded by the Shelburne administration, now seemed the flimsiest of obstacles to conjunction. A seemingly unprincipled alliance of opposites emerged out of the options available in Parliament.

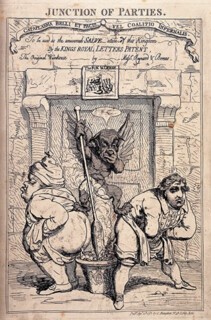

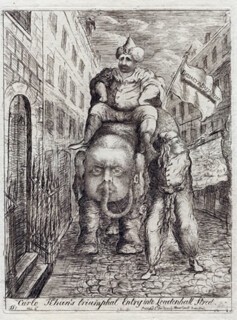

Nevertheless, the Fox-North coalition provoked an outpouring of hostility, not least from three of the most gifted draughtsmen in the history of British political satire: Thomas Rowlandson, James Gillray and James Sayers. Their ingenious cartoons were displayed in print shops and circulated in large official runs, as well as pirated versions and copies. Gillray’s Junction of Parties, drawn on the formation of the coalition in April 1783, depicted Fox and North defecating together into a pot, the contents of which were being stirred by the Devil; even the Prince of Darkness felt compelled to hold his nose against the stench. Attempts by the Fox-North government through its East India Bill to gain control of the patronage exercised by the troubled East India Company inspired Sayers’s memorable Carlo Khan’s Triumphal Entry into Leadenhall Street – where the headquarters of the company were situated – which portrayed Fox as an Oriental despot. The blatantly self-serving enormities of the East India Bill brought about the defeat of the measure and the downfall of the coalition by the end of 1783. Behind the scenes George III put pressure on MPs to reject the bill, but the overthrow of the unnatural coalition was widely celebrated. Rowlandson welcomed its fall in Britannia Roused, or the Coalition Monsters Destroyed.

Curiously, despite the presumption that unprincipled short-termism lay behind the coalition, most Northites stuck with the Foxites in opposition. Coalitions, whether of personal factions or broader parties, became a familiar feature of British politics. The death of Pitt the Younger in 1806 saw the formation of the so-called Ministry of All the Talents, while Lord Liverpool’s administration of 1812-27 brought together proponents and opponents of Catholic Emancipation, then the most controversial issue in politics. Out of the factional instability that followed the demise of the Liverpool regime, the Reform Act of 1832 was introduced by a ministry composed of Whigs and former Canningites. The schism in the Conservative Party in the mid-1840s between Peelites and Protectionists created fertile grounds for coalition within a three-party system. The Aberdeen ministry of 1852-55 was an amalgamation of Whigs and Peelite Conservatives. In time the Peelites – among them Gladstone himself – were absorbed within the Liberal Party. However, the Liberal Party would itself split on the question of Irish Home Rule in 1886, and the Liberal Unionists soon allied with, and were eventually absorbed in, the Conservative Party – itself in effect from this point a kind of unacknowledged coalition.

Although there were no formal government coalitions in the second half of the 20th century, which is the reason the current one feels so alien, the first half of the century was a golden age of rule by coalition. Of course, wartime exigencies played a part in this, producing the coalition of 1915, led by Lloyd George from 1916, and Churchill’s war ministry of 1940; but it was far from the whole story. Lloyd George, a Liberal who felt constrained by the straitjacket of party and whose radicalism did nothing to inhibit his overtures towards the Tories, had been privately scheming to merge with the Conservatives to create a new centre party in 1910, four years before the outbreak of the Great War.

The interplay of Liberals and Conservatives in the first two-thirds of the 20th century constitutes one of the forgotten themes of modern British politics. Lloyd George led a predominantly Conservative government from 1916 to 1922, which fought the December 1918 election under a ‘coupon’ arrangement, a non-competitive pact between the Tories and the Lloyd George Liberals, now semi-detached from the Liberal Party of Herbert Asquith. Further schisms followed. The Liberal Nationals, under Sir John Simon, joined the National Government of 1931 and continued for the next thirty years co-operating closely with the Conservatives. Under the Woolton-Teviot Agreement of 1947 the Liberal Nationals changed their name, confusingly, to the National Liberals, and entered into formal collaboration at constituency level with the Conservatives, standing, more confusingly still, under a variety of designations, not only National Liberal, but National Liberal and Conservative, or Liberal and Conservative. This was not merely an eccentric fringe. Michael Heseltine entered politics as an unsuccessful National Liberal candidate in Gower at the general election of 1959, and Sir John Nott, Thatcher’s secretary of defence during the Falklands crisis, started his career in the Commons as National Liberal MP for St Ives. Only in 1968 were the National Liberals formally wound up and absorbed into the Conservative Party. North of the border the candidates put forward after the formal fusion of Conservatives and Liberal Unionists in 1912 ran until 1965 as Unionists, and as Progressives, Moderates or Independents in local elections. Only since 1965, when the Scottish Unionists changed their official title to Conservative and Unionist, has the party – its cloven Tory hoof now more visible than its Liberal Unionist antecedents – gone into electoral decline.

Many voters in 2010 cast their ballots for the Liberal Democrats because they wanted to punish Labour for its warmongering in Iraq and felt inclined to support a party which seemed plausibly radical, if not to the left of Labour. The Blair years had seen a prolonged, though unconsummated, flirtation between Labour and the Liberal Democrats. Blair wanted to make the 21st century ‘the radical century’ by healing the progressive split between Labour and Liberals which had so often allowed the Conservatives to sneak into government without the support of Britain’s progressive majority. At the Labour Party Conference in 1997, he announced in a far from subtle code: ‘My heroes aren’t just Ernie Bevin, Nye Bevan and Attlee. They are also Keynes, Beveridge, Lloyd George.’ Although Blair’s landslide at Westminster in 1997 frustrated his plan for a progressive realignment in British politics, his dream of Lib-Lab co-operation was realised in the Scottish Parliament, where a Labour-Liberal Democrat coalition governed from 1999 to 2007. Most voters assumed – reasonably enough – that the Liberal Democrats were on the left of British politics. Yet the ironic outcome of the 2010 election was the formation of a coalition government composed of two Thatcherite parties: one which appeared, under the Cameron makeover, to have renounced Thatcherite dogma, only to rediscover it in office, and a smaller party most of whose leadership cadre seem just as happy as the Tories with laissez-faire political economy.

Should the voters have known better? The modestly obscure Orange Book of 2004, edited by David Laws, later briefly chief secretary to the Treasury in the 2010 coalition, with contributions from Clegg, Vince Cable and Chris Huhne, did stress free market and non-statist solutions to problems of public policy – in deliberate contrast to the Liberals’ Yellow Book of 1928, whose policy prescriptions were formulated in large part by Keynes. Still, the party’s recent leaders, Paddy Ashdown, Charles Kennedy – significantly, a former SDP MP – and Menzies Campbell, had all identified clearly with the left of British politics.

Yet post-1945 Liberalism turns out on closer inspection to be deeply implicated in free-market politics. Indeed, during the 1950s, when the Tory Party of Harold Macmillan and Rab Butler seemed happy to muddle through pragmatically, it was the Liberal Party which engaged more enthusiastically with doctrinaire anti-statist politics. In the Butskellite consensus of the 1950s and early 1960s – when there seemed little to distinguish the commitments of Butler and Labour’s Hugh Gaitskell to a central role for the state in a mixed economy – leading Liberals championed the disciplines of the market, what was known, after all, as ‘classical liberalism’. Oliver Smedley, who would eventually leave the Liberal Party in the early 1960s as a result of its support for European integration, promoted free-market views through organisations such as the Council for the Reduction of Taxation, the Society of Individualists and the Free Trade League. Smedley was also involved in the establishment of the pro-market Institute of Economic Affairs, which though it later became intimately associated with the propagation of the Thatcherite gospel, was set up as a non-partisan think-tank and co-directed by a Tory, Ralph Harris, later ennobled by Thatcher as Lord Harris of High Cross, and the Liberal Arthur Seldon. Elliot Dodds, president of the Liberal Party in 1948, celebrated the party’s diverse heritage of anti-collectivism, chairing the Unservile State Group set up in 1953 to renew the Liberal conception of liberty. One member of the Group, the distinguished economist Alan Peacock, suggested – not without some later misgivings about his wording – that ‘the true object of the welfare state is to teach people how to do without it.’

Jo Grimond, the Liberal leader from 1956 to 1967 and again as caretaker in 1976, so idealised sturdy self-reliance that by the early 1980s his opinions sounded more Thatcherite than those of most of the Conservatives in Thatcher’s first – unpurged – cabinet. In a speech on ‘The Future of Liberalism’ at the National Liberal Club in 1980 he complained that ‘the dominant teachings of the last forty years and the teaching of state socialism have undermined in many people the will to exert themselves in any direction.’ Liberals, he argued, must ‘surely look forward to the day when fewer and fewer people need the welfare services as at present constituted’. If this sounded like an echo of the Tory right, Grimond was unrepentant, for the essence of Thatcherism was true liberalism: ‘Much of what Mrs Thatcher and Sir Keith Joseph say and do is in the mainstream of liberal philosophy.’ Grimond’s politics were, of course, not reducible to Thatcherism, and he admired non-statist workers’ co-operatives of the sort run by the Catholic organisation Mondragon in the Basque country. Whether or not the Liberals offered a middle way between socialism and conservatism, it seems clear that free marketeering ideals were no less central in Liberal culture than they were in the pre-Thatcherite Conservative Party.

For many disillusioned voters who supported the Liberal Democrats in 2010, it is Clegg’s casual betrayal of his stance on university fees that is most enraging. They wonder, too, how the Liberal Democrats allowed themselves to be conscripted into David Willetts’s utopian project to privatise higher education. Yet here too the Liberals have form. The independent University of Buckingham was, in large part, the creation of free-market Liberals as an alternative to prescriptive and interventionist state direction of higher education. A major endowment to acquire the site at Buckingham came from the Liberal life peer Lord Tanlaw; and its prime mover and first principal, from 1974 until 1979, was the Liberal academic – later a devoted Thatcherite – Max Beloff. He was succeeded by Peacock, who had long since left the Liberal Party, but remained an exponent of the anti-collectivism characteristic of the Unservile State Group. In 1985 Thatcher chose Peacock to chair an investigation into public broadcasting, whose report reached radical market-driven conclusions. The high road from classical liberalism to Thatcherism is neither long nor winding. The media, it now seems, failed to perform due diligence on our behalf on the Liberal Democrats. Although the outcome of the 2010 election seemed likely to be a hung parliament, the press devoted scant attention to the cultural and policy tensions within a party that was itself a coalition of Liberals and Social Democrats.

Matthew D’Ancona’s In It Together is typical of current media obsessions. A lively book, with many neat turns of phrase, and informed by reliable political antennae, it is a gossipy insider’s account of the current government which focuses largely on personality and temperament to the exclusion of the underlying structures of the coalition. It is based on the author’s interviews with key participants, and – like his address book, presumably – is skewed towards life at the Conservative end of the administration. Here the Liberal Democrats seem pale and shadowy by comparison with their Conservative counterparts. D’Ancona has a fascinating cast of Tory characters, not only those front of house, but the backstage operatives too. Most vivid of all is the maverick Tory strategist and blue-sky thinker Steve Hilton, who wandered around Whitehall in T-shirt and shorts. Nor should we forget the pleasant, self-effacing manners of Cameron’s notorious press secretary Andy Coulson, who is kind to tea ladies and other menial staff. The most significant tensions in the administration, it transpires, are not cross-party difficulties but antipathies within the upper echelons of the Tory Party. In particular, D’Ancona traces the contempt George Osborne feels for the otherwise unemployable Iain Duncan Smith. Osborne, indeed, emerges a much more attractive figure – reflective, compassionate and with a social conscience – than his usual portrayal in the press. But D’Ancona doesn’t engage with the question of how the mildly progressive Liberal Democrats seen on the hustings in 2010 became so quickly and so happily complicit in a Thatcherite reconstruction of the British state which – as it seemed at the time – had no mandate from the electorate.

What does the future hold? Will Clegg’s Orange Book Liberals become so unpopular with floating voters and their own base that they have to be rescued by a ‘coupon’ election? Will they become tomorrow’s National Liberals? And will Labour ever find its way back into government, given the strong ties that now bind the upper ranks of the Tory and Liberal Democrat Parties? After the Fox-North coalition collapsed, the arithmetic in Parliament was still stacked against the new prime minister, Pitt the Younger. When he took over on 18 December 1783, it was assumed that he wouldn’t last until Christmas, and his government earned the nickname ‘the Mince Pie administration’. It lasted until 16 February 1801.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.