In 1888 the Folies-Bergère presented a play called Presse-Ballet, featuring a cast of dancing newspapers and magazines. ‘Le Figaro, Gil Blas, L’Evénement and Le Gaulois danced a quadrille before the public,’ Diana Schiau-Botea writes,

followed by a ‘pas mime’ (dance mime) performed by La Gazette des tribunaux, La Vie parisienne, Le Fashionable and Le Temps. In the next scene, Mlle Bardout made her appearance on stage cracking a whip and leading the cortège of journals. She represented, obviously, the impertinent Courrier français, a trendsetter figure of the press and a regular target of censorship.

For the discerning Parisian audience of the Third Republic, apparently, such publications were prominent and familiar enough to be used as subjects for an evening’s light entertainment.

Bizarre as such a spectacle may seem, it makes sense to think of magazines as characters: like people, they have friends, enemies, social characteristics and guiding motivations (however quixotic). Literary historians these days are discouraged from spending too much time with individual writers, for fear that they will slip into the comfortable grooves of ‘great man’ narratives – a tendency to which scholars of modernism, always a congeries of cults of personality, are particularly prone. But concepts like ‘the market’ or ‘the nation’ can be unwieldy, and often carry scholars some distance from the day to day concerns of those who actually toil in the literary field. And ‘genre’ – a staple of literary analysis in other historical periods – presents a special problem for modernism, which so often took pride in exploding or eluding it. Magazines, then, make for a nice object of study: still recognisable to both writers and readers as ‘literary’ entities, yet governed by social and material constraints, and neatly categorisable in ways that the great modernist authors seem to resist.

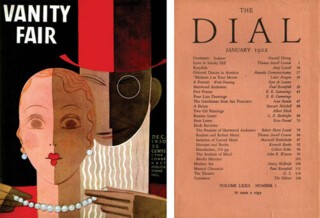

While periodicals are firmly established as a subject in 19th-century literary scholarship, they are still relatively new in modernist studies. A tremendous amount of work is still to be done: in the introduction to the second volume of their Oxford Critical and Cultural History of Modernist Magazines, Peter Brooker and Andrew Thacker point out that the nine-year run of the Dial alone amounts to ‘around 10,500 pages of text and 1200 pages of adverts, assuming an average of 300 words per page; this equals some 3.1 million words to read … about equivalent to reading 21 books of the length of Ulysses.’ Attempting to honour modernism’s internationalist ambition makes the task even more onerous, as every country sprouted its own magazines. A synoptic view of the modernist little magazine is very hard to come by, especially given that, on top of the sheer volume of the material, there are problems of definition: how big can a little magazine get before it outgrows its weight class? And how, for that matter, is size to be measured? By circulation? Price? Frequency? Rates of payment to contributors? Some average measurement of all of the above?

‘The origins of the small review are lost in obscurity,’ Ezra Pound wrote in his 1930 essay ‘Small Magazines’, but Brooker and Thacker do their best to reconstruct them. One point of departure, in Britain at least, was the early 19th-century tradition of the quarterly review. The Edinburgh Review (founded in 1802), the Quarterly Review (1809), Blackwood’s (1817) and the Westminster Review (1824) catered to an elite interested in literature, philosophy and current events. They survived by appealing to a broad group of readers, and early little magazines were formed in reaction to the complacent miscellany of the quarterlies, which had come to be regarded as stale and bourgeois: in 1936 Clifford Bax sneered that ‘quarterly magazines of art and literature belonged to the age of silk hats, hansom-cabs, drawing rooms and permanent marriages.’ In place of middle-class generalism, the little magazines insisted on the importance of having a programme. ‘A review that can’t announce a programme probably doesn’t know what it thinks or where it’s going,’ Pound wrote, and indeed the idea of a programme and a direction was often more important than the direction itself, which usually changed considerably over time.

Many of the early little magazines, far from being self-consciously ‘modernist’, were antiquarian throwbacks. Fin-de-siècle periodicals like the Yellow Book, the Chameleon and the Savoy took inspiration from William Morris, Charles Ricketts and other luminaries of the Arts and Crafts movement, favouring medieval typefaces, elaborate woodcut illustrations, uncut pages and plenty of white space. An equivalent international vogue for ‘ephemeral bibelots’ was inspired by the Montmartre-based Chat noir. In America, slim productions with names like the Fad, Impressions, A Little Spasm and Whims promoted a Wildean cult of decadence, and were mocked by the naturalist Frank Norris in his novel The Octopus as ‘little toy magazines’. Symbolist-inspired bibelots appeared in Berlin, St Petersburg, Copenhagen, Lisbon, Alexandria and elsewhere.

Around the same time, the market for publications was exploding. It’s estimated that 7500 magazines were published in the United States in 1905, up from 575 in 1860, with Britain and Europe experiencing similar increases. An insistence on the interrelation of ‘big’ and ‘little’ magazines is a particularly valuable aspect of the Oxford volumes, whose examples range from the minuscule (Laura Riding and Robert Graves’s Focus, a ‘private magazine, for and by friends’, or Georges Bataille’s Acéphale, the house organ of his eponymous secret society) to the massive (Vanity Fair and the New Yorker, with circulations in 1930 of 90,000 and 100,000 respectively). The influence cut both ways: Henry Harland brought hard-nosed American newspaper expertise to the launch of the Yellow Book, and ‘slick’ magazines like Vanity Fair and Esquire regularly published modernist writers like Cocteau, Hemingway, Lawrence, Dos Passos and Djuna Barnes. (The New Yorker, founded in 1925, was considerably less daring: the fiction editor, Katharine White, rejected work by Gertrude Stein because ‘she was not allowed to buy anything her boss didn’t understand.’) H.L. Mencken and George Jean Nathan subsidised their succès d’estime the Smart Set with ‘louse magazines’ such as Parisienne, Saucy Stories and Black Mask. Die neue linie, featuring work by Bauhaus designers such as László Moholy-Nagy, Herbert Bayer and Irmgard Sörensen-Popitz, was a revamp of the mass market German women’s magazine Frauen-Mode and a probable influence on Vanity Fair’s designer Mehemed Agha. Mass market satirical newspapers and magazines were also a breeding ground for avant-garde aesthetics: the gossipy Parisian daily Gil Blas published Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, and the Dadaist George Grosz was influenced by the cartoons in German satirical weeklies like Simplicissimus and Jugend.

Despite their proximity to the mass market, distaste for the vulgarity of commerce was common among little magazine editors, and some flaunted their anti-professionalism: Man Ray’s Ridgefield Gazook, for instance, boasted that it would be ‘published unnecessarily whenever the spirit moves us. Subscription free to whomever we please or displease. Contributions received in liquid form only.’ But most magazines found they had to make compromises. Many, of course, were supported by wealthy patrons: Lady Rothermere, the wife of the press baron Harold Harmsworth, funded T.S. Eliot’s Criterion from 1922 to 1927; the shipping heiress Bryher (Annie Winifred Ellerman) bankrolled both Desmond MacCarthy’s Life and Letters, a Bloomsbury outlet, and her own film magazine Close Up; the painter William Nicholson supported Robert Graves’s Owl; and, in pre-Revolutionary Russia, Diaghilev’s Mir Iskusstva was funded by Nicholas II. Sometimes patronage was diffused: Harriet Monroe induced affluent Chicagoans to pledge $50 per year over five years to Poetry by convincing them that her fledgling magazine would be ‘the most important aesthetic advertisement Chicago ever had’.

Other magazines accepted commercial advertising, a practice much more common in the US than in the UK or Europe, where ads tended to be strictly literary or publishing-related. There were other tricks: expats and émigrés – notably Margaret Anderson and Jane Heap at the Little Review and George Plimpton at the Paris Review – were sometimes able to take advantage of favourable exchange rates. Some publishers financed themselves by playing the art market; the Surrealists funded many of their activities in this fashion, as did the Weimar magazines Die Sturm and Die Aktion. After the Second World War, philanthropic organisations like the Rockefeller Foundation meted out grants to a few of the more distinguished magazines left standing ($2400 to Scrutiny in 1949, and a whopping $22,500 to John Crowe Ransom’s Kenyon Review over the course of five years, from 1947 to 1952). Literary prestige was, on occasion, converted into capital, as in the case of Cid Corman’s Origin, an important venue for Charles Olson and the Black Mountain School of poets. According to Tim Woods, the second series (1961-64) was financed in part by the sale of manuscripts relating to the first series (1951-57) to Indiana University, and the third series (1966-71) by the sale of materials relating to the second and third to Kent State.

The most successful long-term survival strategies, though, involved attaching your magazine to an institution that could help foot the bills and provide publicity and administrative support. Book publishers, which often supported little magazines (it looked good and attracted new writers to their lists) were among the most common supporting institutions. Faber and Gwyer acquired the Criterion in late 1926; John Lehmann’s New Writing was published by the Bodley Head and later by Leonard and Virginia Woolf’s Hogarth Press, and issued a series of popular anthologies with Penguin. Both La Nouvelle Revue française and later the Surrealist organ Littérature were affiliated with Gallimard. In Italy, Ugo Ojetti’s pro-Fascist Pan was produced by Rizzoli in order ‘to steer its literary-minded readers towards “I Rizzoli Classici”, high-quality, reasonably priced copies of the classics edited by none other than Ojetti himself’.

But little magazines were also frequently affiliated with bookshops, trade unions, social and philanthropic organisations, art galleries, universities, theatres and cabarets. Partisan Review, which would become the defining American little magazine of the postwar period, began as an official publication of the New York John Reed Club. W.E.B. Du Bois’s Crisis was underwritten by the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, and A. Philip Randolph and George Schuyler’s Messenger had the support of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. Yeats’s magazines Beltaine and Samhain were issued to provide publicity and explanatory material for performances at the Irish Literary Theatre and the Abbey respectively. The Cabaret Voltaire published a one-off ‘propaganda magazine for the bar’, bringing descriptions and transcriptions of Dada events to an international public unable or unwilling to attend an avant-garde performance in a ‘very dirty corner’ of Zurich.

There were also affiliations with political parties, particularly in continental Europe, where the artistic avant-garde played a more significant role in national politics than in America or Britain. The Futurists were instrumental in Mussolini’s rise to power, joining forces with the Fascists and the Arditi (demobbed infantry troops from the First World War) to form the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento (Italian League of Combatants), an alliance dramatised in Rachel Kushner’s novel The Flamethrowers. The Russian Futurists were more ancillary to the 1917 Revolution: their emphasis on transrational poetry and ‘words in freedom’ wasn’t immediately suited to Bolshevik propaganda, though the little magazine LEF, whose regular contributors included Mayakovsky, Pasternak and Babel, did attempt to develop something called Communist Futurism. Breton and other Surrealists tried to align themselves with the Parti Communiste Français, with decidedly mixed results. Other little magazines were forced into political affiliations by a change of regime: under Drieu La Rochelle, the Nouvelle Revue française became a venue for fascist apologetics after the German occupation in 1940; the Bauhaus-affiliated die neue linie was, Patrick Rössler writes, ‘a figurehead … and fig leaf’ for the modernist movement under the Third Reich, allowing the Nazis to make a token display of open-mindedness and cultural tolerance.

In the US and Britain political commitments were more idiosyncratic. A.R. Orage’s New Age, for instance, evolved from a Christian Socialist newsletter into a forum for the economic theories of Major C.H. Douglas and the esoteric spiritualism of Gurdjieff. The importance of anarchism to many of the most vital little magazines of the century’s first two decades has been underplayed – in part, perhaps, overshadowed by the later influences of communism and fascism. Greenwich Village was a nexus of anarchist energy in the early 1910s, thanks largely to Eastern European immigrants. The Little Review, best remembered for serialising 14 chapters of Ulysses, was enamoured of Emma Goldman: its editor, Margaret Anderson, called her ‘the most challenging spirit in America’. In Britain, Dora Marsden gradually moved the Freewoman away from suffragism towards the individualistic anarchist philosophy of Max Stirner, renaming the paper the Egoist in 1914.

But the two most important ideologies in the history of the little magazine were without question nationalism and its country cousin regionalism, both on the rise in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Often the fortunes of magazines were closely tied to the urban spaces where they were produced. Paris and London are unusual in the extent of their dominance; more often we find a tale of two cities, each competing for capital status: Munich v. Berlin; Rome v. Milan; New York v. Chicago; St Petersburg v. Moscow. On a global level, the unstable relationship between literary centre and periphery, as Pascale Casanova argued in her 1999 study The World Republic of Letters, made a variety of positioning strategies possible. Many editors of little magazines cosied up to the Parisian avant-garde, insisting on the French (and, less often, the British) example as the key to cultural modernisation. Others had a more adversarial attitude towards the existing centres of power. The Yugoslav magazine Zenit celebrated Slavic ‘barbarogenius’ and denigrated Western decadence. An editorial in Wales declared that ‘British culture is a fact, but the English contribution to it is very small … There is actually no such thing as “English” culture: a few individuals may be highly cultured, but the people as a whole are crass.’

Many emerging nationalist movements took inspiration from the avant-garde, particularly Futurism, although the relationship could be quite complex, as a 1909 interview with Marinetti by Mihail Drăgănescu in the Romanian fortnightly Democraţia shows. In his Futurist Manifesto, Marinetti promised to ‘destroy the museums, libraries, academies of every kind’ and compared museums to cemeteries. Drăgănescu, in response, chided Marinetti for the privilege underlying his iconoclasm:

You’ve become bored with your many museums, libraries and antiquities, but we Romanians have almost no museum, almost no library. You have too many professors, too many archaeologists, museum guides and antiquaries. We, alas, have almost none, we are a poor young country … We don’t have museumcemeteries [sic] because there was nothing for us to bury.

The Futurist Manifesto, first published in 1909 in Gazzetta dell’Emilia and widely translated and distributed thereafter, was both one of the earliest and the most influential documents of the avant-garde; it may have helped that the bellicose rhetoric of Futurism had an immediate application to nationalist political movements already underway. It aroused considerable interest in countries as far-flung as Spain, England, Sweden, Russia, Switzerland, Czechoslovakia and Poland. Marinetti’s genius for publicity also helped generate a tidal wave of tendencies ending in ‘ism’, some of them, like Imagism and Surrealism, relatively familiar, others (nunisme, instantanéisme, noucentisme, poetism, formism) more recherché. Fernando Pessoa may hold the record, with three original isms to his name: the relatively seminal Paulismo, as well as the non-starters Sensationism and Intersectionism. By the end of the 1910s, an ism backlash had begun. ‘As convenient descriptions we do not object (save sometimes on grounds of euphony) to the terms Futurist, Vorticist, Expressionist, Post-Impressionist, Cubist, Unanimist, Imagist,’ J.C. Squire wrote in the London Mercury in November 1919, ‘but we suspect them as banners and battle-cries, for where they are used as such it is probable that fundamentals are being forgotten.’ Robert Coady’s magazine The Soil was more categorical, lamenting in 1917 that ‘there are those whose metaphysical proclivities have been excited to a dizzy hysteria by ismism.’

Hesitation or scepticism towards the avant-garde could easily give way to full-fledged hostility, particularly in the mainstream press. Pessoa and the other contributors to Orpheu were mocked by Portuguese newspapers as ‘poor maniacs’ who ‘instead of running around naked in the street doing somersaults have committed their idiocies to paper and are now sitting back rubbing their hands, waiting for the bourgeoisie to scold’. In Nazi Germany, unsurprisingly, anti-modernism and anti-Semitism were linked; Christian Weikop notes that in Fritz Herzog’s 1940 history of German little magazines, ‘every publisher, editor, critic and artist of Jewish descent was identified as such with “Jude” given after their name.’ In the US, a vigorously nonsensical public debate broke out about the relationship between ‘free verse’ and ‘democracy’ – H.L. Mencken called it ‘the current pother about poetry’ – with radicals like William Carlos Williams and Alfred Kreymborg linking free verse to the tradition of Whitman while traditionalists like Joyce Kilmer and Louis Untermeyer staunchly denounced it as a dangerous foreign import.

The heyday of the modernist little magazine extended from about 1910 through the 1930s. (The European volume cuts off in 1940, while the British and Irish one extends to 1955 and the American to 1960.) When and why exactly modernist magazine culture began to decline is a matter of some speculation. The Depression and the rise of totalitarian regimes killed off many magazines, and the Second World War – which both depleted the pool of potential contributors and posed logistical challenges like paper rationing – did still more damage. In December 1942, Cyril Connolly described Horizon as ‘a magazine which to defeat the call-up had learned to appear without writers, which can see only in the blackout, which can comment only on disaster, or to maintain itself in a paper shortage’. Horizon’s ‘eclectic’ stance was to some extent a practical matter: ‘however much we should like to have a paper that was revolutionary in opinions or original in technique,’ Connolly wrote in 1940 in the magazine’s first issue, ‘it is impossible to do so when there is a certain suspension of judgment and creative activity … Our standards are aesthetic, and our politics in abeyance.’

The evolution of publishing played its part. From the 1940s, the mass market became considerably more hospitable to modernism, especially in the US. Magazines like Esquire were paying Hemingway, Faulkner, Dos Passos and Pound far more than the little magazines were able to afford. R.J. Ellis observes that the Beats were the first American writers in the avant-garde tradition to bypass the little magazine culture entirely: though Kerouac, Ginsberg, Burroughs and other major Beat writers did contribute to small publications like Ark II Moby I, Evergreen Review and Big Table, their reputations had already been made, whether in larger venues or through live performances; none of them played a major role in editing a little magazine. By the 1950s, successful little magazines were likely to be affiliated with colleges or universities, and to emphasise literary criticism over creative writing. A notable exception was the Paris Review, which, as Christopher Bains writes, sought through its interview series to take ‘modernism back from the critics and universities, rendering it to the writers, giving them a central role in shaping the reception of their work’. While new little magazines continued (and continue) to appear, particularly in the wake of the ‘mimeograph revolution’ of the 1960s, they were now much more marginal to the broader literary culture. The foundation in 1963 of the New York Review of Books (not discussed in the Oxford history) marked a return to the miscellanies of the early 19th century.

The miscellany, rather than the mass market publication, may well be the real antithesis of the little magazine. In his 1964 essay ‘Fifty Years of Little Magazines’, Connolly made a distinction between ‘dynamic’ and ‘eclectic’ magazines: ‘Some flourish on what they put in, others by whom they keep out … The dynamic editor runs his magazine like a commando course where men are trained to assault the enemy position; the eclectic is like a hotel proprietor whose rooms fill up every month with a different clique.’ Again and again in the pages of Brooker and Thacker’s enormous compendium we find some version of the notion that the true enemy of the modernist magazine is not size – many of these magazines desired to reach as large an audience as possible – but ideological indiscrimination, or pluralism. In this sense, it seems right to speak of the modernist tradition as an essentially anti-liberal one. ‘It is, curiously enough, not so important that an editorial policy should be right as that it should succeed in expressing and giving clear definition to a policy or set of ideas,’ Pound wrote in 1930. ‘Healthy reaction, constructive reaction, can start from a wrong idea clearly defined, whereas mere muddle effects nothing whatever.’

The force of modernity is largely centrifugal, drawing a hundred disparate ideas away from the centre until it’s not clear that it even makes sense to speak of a ‘centre’ any more; the dynamic little magazine does its best to provide a centripetal counterforce, even at the risk of simplifying and reducing the real complexity of the modern world. (Pound doubted ‘if an effective programme can contain more than three ideas’.) It’s this centripetal tendency, which insists on opposing some idea or aesthetic to the ‘mere muddle’ of modernity, that distinguishes modernist magazines, for better and worse. Their centres never hold for long, but while they do, it briefly seems as if literary history might be a matter of programme and agenda rather than fortune and happenstance; as if somebody might be in charge of things after all.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.