Just as some faces are a gift to the photographer (Artaud, Patti Smith), so certain lives are a gift to the biographer. These are, broadly, of two types: the hard and gemlike, abbreviated, compressed, intense; and the lengthy, implausible, exfoliated, whiskery, picaresque. Vehement or even violent emotion is good, overt drama, prominent contacts or associations, sudden changes of orientation, movement through different societies and settings. Physical distance is helpful (the father of letter-writing), marriages (more than one), a hint of scandal or controversy, achievement and neglect, both in moderation (poverty is a great preservative, celebrity or laurels a terrible corrosive, too obvious or excessive greatness is dreary). A late flowering is ideal, but not essential. For the former, one might nominate Trakl, Laforgue, Keats and Shelley (I don’t think I breathed while I was reading Richard Holmes’s Shelley: The Pursuit all those years ago); for a rare, artful blending of long and short, one can’t do better than Rimbaud and Hölderlin; and for the latter, Hamsun, Yeats, Shaw – and Bunting. Incidentally, or maybe not, Bunting also shows beautifully on film and still photographs, from the waggingly imperialled steely young man (‘one of Ezra’s more savage disciples’, Yeats called him) posing in Rapallo in 1930 or 1931 on the cover of A Strong Song Tows Us and the New Directions Complete Poems, to the waggingly eyebrowed, scruff-bearded, snaggle-toothed, twinkling-eyed dome he presented as an old man in his eighties.

Basil Bunting – not a nom de guerre but his actual given name, as Pound hastened to assure a doubtful Harriet Monroe, long-suffering and mostly tame editor of Poetry – was the missing link back to the heyday and personalities of modernism. He wrote little (‘The mason stirs:/words!/Pens are too light./Take a chisel to write’), but what he wrote ever more powerfully endures. Reading him now, there is an overpowering drench of the 1920s and 1930s, and a suggestion of how the style of progressive verse might have gone on, if Pound hadn’t disappeared into funny money, the Cantos and obloquy, or Eliot into verse drama and High Anglicanism. Bunting’s Complete Poems are a tantalisingly small and pure uchronia, and as for his life, his model in these things was Walter Raleigh.

A Life of Bunting, then, was for many years the most obviously ‘missing’ book I could think of. For all the reasons – the ticked boxes – above; for a rather beautiful relation between the life as old as the century (1900-85) and the small, sharply flavoured work (the Complete Poems are with difficulty bulked up to 240 pages: they make Elizabeth Bishop look lax if not garrulous); for the unusual way time – history – is precipitated in a literary life. ‘Bunting had a knack of being in the thick of things,’ Richard Burton observes in this first proper biography: it feels like a flagrant understatement. Adventures of the mind are two a penny; here are actual, palpable scrapes: individuals sent to kill him, crowds baying for his blood, a life spent on four continents (and at sea), never far from the breadline. In 1934, when he wasn’t even halfway into it, when most of the most outlandish things still lay ahead of him, and he was stuck in the Canary Islands, William Carlos Williams wrote: ‘Bunting is living the life, I don’t know how sufficiently to praise him for it. But it can’t be very comfortable to exist that way. I feel uneasy not to be sending him his year’s rent and to be backing at the same time a book of my own poems.’ Imagine Tintin not as a supposed journalist with a cowlick, but Haddock-bearded and a rare poet, and you get Bunting. Even if he had written nothing at all, his life would still be worth telling: as an extravagant shape, as an example of what is possible, or just to give oneself a fright.

Bunting was born the son of a progressively minded doctor in Scotswood-on-Tyne. He was not a Quaker, but was educated at Quaker boarding schools. In 1918 he was sent to prison for being a conscientious objector; this seems to have involved a certain deliberateness, even wilfulness on Bunting’s part. Quite often, his life frays into uncertainty, competing versions, colourful mists of low factual density, ultimately the beguiling wraiths of myths, suitably embellished by himself or the other gifted embellishers among whom he mostly lived. (Take a bow, Ford Madox Ford, take two!) Pound tells the story (in Canto 74) of ‘Bunting/doing six months after that war was over/as pacifist tempted by chicken but declined to approve/of war.’ Burton agrees that the Sun-worthy ‘Pacifist Tempted by Chicken’ – when Bunting went on hunger strike, a freshly roasted chicken was said to have been brought to his cell on several successive days by his jailers – sounds a little too good to be true. On his release he enrolled in the newish London School of Economics, but left in 1922 without taking his degree. He was radical (the lovable politics of the Occupy movement), brilliant, but also ‘a great poseur’, feckless, improvident and prone to ‘nerve storms’: the type of individual who looks, if not to poetry, then to some other re-evaluative hierarchy to adjust his low standing, his perceived lack of usefulness, his reversed poles. A scalene peg. He was impatient with institutions, with convention, with medium-term thinking and planning, with England. He began to go abroad: to Denmark (‘on his bicycle the Dane is a beautiful creature, but off it he does not feel at home, and looks as awkward as an automaton’); to Paris; to Rapallo. In 1924 he met Pound there, supposedly – the mythopoeic embellishment – at the top of a local hill. ‘Villon’, his first long poem, was written in 1925, and published, with Pound’s help (one might say, passim), in Poetry five years later. The poem won a $50 prize, which straightaway – that’s hand to mouth – went to pay the expenses incurred by the birth of a daughter, Bourtai, in 1931. (Bunting’s children with his first, American wife, Marian, had Persian names; two later children, born to his Persian wife, Sima, were called Maria and Thomas.)

Between 1925 and 1940, he was really all over the place – not that that couldn’t be said about the time before and much of the time after as well. He came and went between Rapallo and England, where he took a job as a music critic; he did good work, breaking lances for very old and very new music, Monteverdi and Schoenberg alike, but he was never enthusiastic about employment in general, or journalism in particular, and was always grateful when they lapsed from him. (I think of Les Murray’s lovely and perplexed line, ‘In the midst of life, we are in employment.’) His relations with London, and with ‘southrons’ in general, were not straightforward, though not as negative as they are sometimes painted either. He acquired a temporary patron in the form of a rich American widow called Margaret de Silver. He had book plans, rather English subjects, all: one on Dickens, one on music hall, one on prisons, but he was never that sort of jobbing writer. He lived for six months in 1928 in a shepherd’s cottage in Northumberland. He visited Berlin, and (perhaps the only Englishman to do so) hated it. In Venice he met Marian Culver – she was a recent Columbia graduate ‘doing’ Europe – and married her on Long Island. He spent time in New York with his Poundian confrères Williams and Zukofsky, but (small surprise) there were no openings for him in the States: ‘It was better to go back and see how long we could live on nothing in Italy – rather than the very short time you can live on nothing in the United States.’ It is a little hard to imagine how the Buntings got by in Italy, and the biography doesn’t really help. ‘We have very few descriptions of the Buntings’ family life at this (or any other) time,’ Burton notes. Marian had a remittance from her family; Bunting may have been helped by his mother (who joined them in Rapallo periodically; his father was dead); I don’t think there was much paid work involved. Bunting advances the perverse and implausible claim: ‘It seems as though Italy were the only climate in which I can get up any energy.’ He sailed, he taught himself Persian, but when you look at him lolling in white ducks and singlet, an eccentric monument, ripped, evenly tanned and rather dazzling, everything about him seems to scream dolce far niente at you.

Then, whether it was because of the increasing expense of Italy, the disagreeable impact of fascism, the still more disagreeable relaying of fascist and anti-Semitic sayings from his friend Pound, or just his own innate restlessness, Bunting upped sticks and the family moved to the Canary Islands, a Spanish possession a hundred kilometres off the coast of southern Morocco:

Just got back from a visit to the local Sahara. Seven or eight miles wide and ever so many long, and covered with loose pieces of pumice about as big as a man’s head. A sort of pale grey thorn scrub, and a few camels eating it. A sort of green shrub, much rarer, and a goat or two eating that.

A second daughter, Roudaba, was born on Tenerife in 1934, but mostly Bunting was pretty wretched. He wrote to Pound that ‘the people of this island [are] so unspeakable, and the food so uneatable, they make prolonged residence impossible, in spite of great cash saving.’ Out of aesthetic disappointment or anthropological pique, he declined to learn Spanish. (Bunting, born during the Boer War as Ladysmith was relieved, had a rather empire way about him: smartly dividing the world into good and bad natives, with little in between; but for the appearance of that brusque trait, he would seem to have made rather a bad expatriate.) At the end of three years and much moving around, Bunting ‘escaped from Tenerife’, only, alas, to return to London.

Shortly thereafter, Marian, pregnant with a third child, borrowed a pound from her mother-in-law, took her daughters, went back to Wisconsin and divorced her husband of seven years. Bunting took it unexpectedly hard. He wrote little or nothing for the best part of thirty years. Pound observed drily – in his customary horrid epistolary style – ‘las’ I heard of Bzl his wif had left and took the chillens. It wuz preyin on his cerebrum/why? Some folks iz never satisfied.’ Bunting managed to buy a fishing boat, and lived on it for a year – the Thistle: even the name is a sort of protest – cutting down on his expenses and his human contacts, drifting in self-imposed quarantine. It’s a suggestive image for a man who hadn’t been able to make a go of things abroad, couldn’t then stand to be on his home island, and could only regroup in the changeable element. He sold the boat at a decent profit, went to America, achieved nothing (wasn’t even able to see the children), came home again. The war arrived at a good time for him – as wars are apt to do for individuals in abject or complicated circumstances – though he had a hard time enlisting.

In July 1940, he was accepted by the RAF, after being turned down by the army and the navy. (Having very poor sight – he wore glasses as thick as pint-pots – he was supposedly allowed by a sympathetic doctor to memorise the eye chart.) He began in Balloon Operations in the North Sea, then was sent to Persia, fought his way from Basra to Tripoli, served in Malta, then in the Sicilian invasion, and in 1944 returned to Persia, this time as an intelligence officer. It wouldn’t have been Bunting if it hadn’t involved the occasional spree; driving the lead lorry of a large convoy in Scotland and spotting a brewery, he promptly took the turning, which resulted in the inevitable free drinks all round – but it wouldn’t do to overstress these Compton Mackenzie-style yarns, which seem to crop up variously at all points of Bunting’s life. The astonishing thing, rather, is that he performed at all: he worked, he was reliable, he was smart, he was respectful, ‘all the stupid military things’, as he put it. For the suspicious, anti-establishment, conscientiously objecting Quaker boy of twenty years before, it was quite a turnaround. Perhaps it was the acceptance of a higher, common cause – the defeat of totalitarianism – to which he submitted himself; perhaps the corners of the air force and intelligence in which he found himself were sufficiently unconventional and improvised and reshuffled to attract and keep his loyalty and devotion. Or again, it was the empire, which, as a sort of shuffling of home and abroad, didn’t have quite the stifling values of home. ‘Action is a lust,’ he discovered, for which it was perhaps worth abandoning the reflective life, not that it was ever a consciously taken decision. At any rate, ‘I learned my wing-commander act.’

Then of course, there was Persia. Bunting adored Persia, ‘a country where they still make beautiful things by hand’. Isfahan was his favourite city in the world. He loved the courtliness, the hospitality, the pleasure-seeking, the childlike colour and drama of the Persians: after all, they sang to the same qualities in him. He delighted his hosts by having named his children after their heroes and by speaking an antique form of their language that he had learned from reading the tenth-century poet Ferdowsi: ‘It was as if someone came along in England speaking a Chaucerian mode.’ If there was a place for him anywhere, then surely it was in the wonderfully named Luristan. The tribal Bunting took tea (and much else) with the tribes of Persia. In 1947 and 1948 he assisted our man in Tehran, met and married a Kurdish girl, Sima Alladadian; left the Foreign Office – a sort of sideways move – to become Tehran correspondent for the Times; in 1952 he was finally expelled by the nationalist (and nationalising) Mossadeq government. It was a loss all round, because Bunting seems to have understood and liked the place, and managed to operate in it better than most. A press colleague admitted: ‘He told us two years ago what was going to happen in Persia, & the Foreign Office said Pooh! & so did the oil people.’ He wasn’t easily intimidated either. At the Ritz in Tehran there was a sanctioned demonstration against him that Bunting insisted on joining: ‘I walked into the crowd and stood amongst them and shouted DEATH TO MR BUNTING! with the best of them, and nobody took the slightest notice of me.’ As I say, Tintin.

If it had happened in more recent times, Bunting would have enjoyed kudos as an expert, with expensively serialised memoirs and semi-detached television appearances on daytime sofas to look forward to. But in 1952, things weren’t like that. He returned to England, with a new young family, to find himself basically unemployable. The Buntings moved in with his mother, and braced themselves for hard times. Long absence disqualified Bunting for state assistance, and the better part of what he had done while away did not redound to his credit for the simple reason that it was all too hush-hush. He was rejected for better jobs, and did badly paid clerical tasks: proofreading – a man with his eyesight – bus and train timetables, gently revising sensitive trade-unionists’ grammar. A man meeting him for the first time was dumbfounded by his humdrum semi-military appearance: ‘the story-book image of a scoutmaster’. In 1954, he got a job as sub-editor (working nights) on the Newcastle Daily Journal; in 1957, he moved to the Evening Chronicle.

For ten years – not the dishonoured prophet but the returned expat and ex-poet in his own country – he led a plaintive, low-key existence, grumbling about money, feeling he had missed his moment, whenever that might have been. It was from this condition that he was rescued by the young Newcastle poet Tom Pickard, who, having picked up a couple of leads as to Bunting’s importance and local availability, telephoned him and shortly afterwards turned up on his doorstep. With Pickard’s encouragement, Bunting was tied into the writing scene in Newcastle (he read several times at the newly opened Morden Tower), he found publishers for some of his old poems, and even began writing again. His long poem Briggflatts was written on a commuter train; the last of his ‘sonatas’ (it’s only twenty pages), it was cut down from something apparently very much longer. It was published to widespread acclaim in 1965, and Bunting was rediscovered (mostly for the first time). He was able to retire from the Chronicle, and parlay his continuing existence – here after all was something like the Stephen Spender of modernism, he had known Yeats, was an associate of Pound’s, could remember Eliot as a progressive – into readings and teaching jobs in America, grants from the Arts Council and Northern Arts, radio and television appearances on the BBC, and then, surely mistakenly, honorific presidencies (in the sense that he was honouring them) of the Poetry Society (at a particularly horrible time in its history) and Northern Arts. The scoutmaster was elbowed aside by a strange new act: the Grand Old Man, the English Celt (listen to the recording of Briggflatts). Oxford published his Collected Poems in 1978, and a posthumous Uncollected Poems in 1991. He continued to be shunted around from house to house (he never seemed to find rest or comfort), wrote little, but had leisure to opine and reminisce. He didn’t have much use for the work of his contemporaries and juniors (his fellow Celts David Jones and Hugh MacDiarmid were partial exceptions), but was on the whole pleasant about it. A breezy manner (‘Unabashed boys and girls may enjoy them. This book is theirs’), a few eclectic names – Pound, Zukofsky, Whitman, Wordsworth, Spenser, Horace, Villon, Ferdowsi, Manuchehri – and a few ideas (poetry as music, poetry as carving and parsimony) resonated perhaps a little more after the stifling Amis-Larkin 1950s and 1960s. The Beatles – Northern Songs! – bought expensive limited editions of his books, and took care to be seen reading them. He died in hospital in Hexham in 1985; his ashes were scattered in the Quaker graveyard at Brigflatts that he had first visited as a small boy in the early century.

And the poetry? It’s acquired an oddly strategic quality. So much depends on … Basil Bunting. Without Bunting, Pound is a greatly diminished figure, the enabler of Joyce and Eliot and Hemingway, but of no real consequence since the 1920s; with Bunting he remains central past the 1960s, and England for the first time plays in modernist colours alongside Ireland and the United States. Donald Davie wrote that Bunting was ‘very important in the literary history of the present century as just about the only accredited British member of the Anglo-American poetic avant-garde of the 1920s and 1930s’. Yes, he holds the century together, but almost more important he holds the two sides of the Atlantic together as well. Burton cites Martin Seymour-Smith, for whom Bunting was the only English poet to solve the problem of how to assimilate the lively spirit of American poetry without losing his own sense of identity (a nice and a true description). So somehow the persistence and adequacy of British English in the 20th century is also dependent on Bunting. I think all of this is true, and obviously nowhere more so than in Briggflatts, which looks across fifty years at a harsh, cold, bright reality in curt speech that is in touch with Pound’s ‘The Seafarer’. Hence, America, modernism (the sealing couplet!), the century and England all together, with a touch of sweetness:

Stocking to stocking, jersey to jersey,

head to a hard arm,

they kiss under the rain,

bruised by their marble bed.

In Garsdale, dawn;

at Hawes, tea from the can.

Rain stops, sacks

steam in the sun, they sit up.

Copper wire moustache,

sea-reflecting eyes

and Baltic plainsong speech

declare: By such rocks

men killed Bloodaxe.

Partly following Bunting himself, Burton is often at pains to defend him from Pound. He groans when a critic remarks that you could track Bunting ‘everywhere in Pound’s snow’. But I think it’s a matter of the intention with which his name is brought up: Pound is not only and everywhere a menace, and in any case Bunting was never his creature. ‘I don’t want to minimise my debt to Ezra nor my admiration for his work, which should have “influenced” everybody, but my ideas were shaped before I met him and my technique I had to concoct for myself.’ Bunting gave Pound the magnificent punny formula ‘DICHTEN = CONDENSARE’: poetry is not so much to make new as to make dense. He went through Shakespeare’s sonnets cutting lines and shuffling phrases. I can’t imagine a Pound reader not enjoying Bunting (the change of ear and vernacular), and vice versa. Both seemed to enjoy writing English like a foreign language, whether it’s Pound’s ‘The harsh acts of your levity./Many and many./I am hung here, a scare-crow for lovers’ or Bunting’s ‘You idiot! What makes you think decay will/never stink from your skin?’ The distance between translation and original poem, between lyric and ‘mask’ or ‘persona’ is closed. You get Bunting as a Japanese hermit (‘I do not enjoy being poor./I’ve a passionate nature./My tongue/clacked a few prayers’), Bunting as a Middle Eastern nymphet (in ‘Birthday Greeting’), Bunting as a queasy, Eliotish visitor to Berlin (‘Women swarm in Tauentsieustrasse./Clients of Nollendorferplatz cafés,/shadows on sweaty glass,/hum, drum on the table/to the negerband’s faint jazz./Humdrum at the table’), Bunting as a splendidly tiddly businessman (‘I’m not fit for a commonplace world/any longer, I’m/bound for the city,/cashregister, adding-machine, rotary stencil./Give me another/double whiskey and fire extinguisher,/George. Here’s/Girls! Girls!’), Bunting as an ageing madam in ‘The Well of Lycopolis’. Language becomes the sum of its possibilities. Bunting extended Pound’s writ to Persian and the Queen’s English. To me, it’s a virtuous and a mutually reinforcing association. One reads both with the same senses and nerves and parts of one’s brain, the author of A Lume Spento (1908) and Lustra (1916) and the author of Redimiculum Matellarum (1930) and Loquitur (1965), the author of Cathay (1915) and the author of Chomei at Toyama (1932), the author of the Cantos and the author of Briggflatts (1965). Both espoused a fresh, flexible, original style, the style of young men for thousands of years, assembled from beauty, learning, satire and irreverence. The Bunting who in the early 1920s and in his own early twenties first approached Pound, wrote: ‘I believed then, as now, that his “Propertius” was the finest of modern poems. Indeed, it was the one that gave me the notion that poetry wasn’t altogether impossible in the XX century.’ Pound, I think, remained for Bunting the poet of ‘Homage to Sextus Propertius’, and nothing Bunting wrote is very far from it: the ‘Sonatas’, the ‘Odes’ and the ‘Overdrafts’, as Bunting amiably called his own translations.

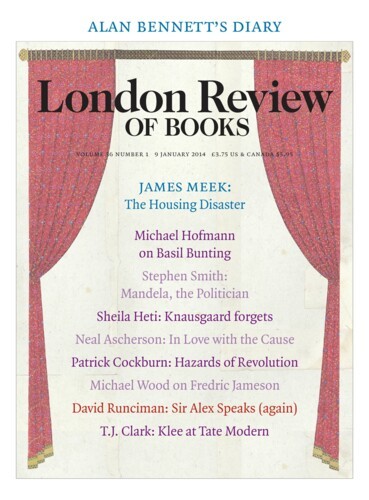

T.S. Eliot, who failed to include the ‘Homage’ in his 1925 selection of Pound’s poems, was therefore true to form in not publishing Bunting either. As late as 1952, twenty years after Pound’s Active Anthology (published by Faber) in which Bunting took up a quarter of the pages, Eliot rejected him (‘too much under the influence of Pound, for the stage which you have reached’). By my reckoning, the last three poetry editors at Faber have gone on bended knee to Canossa (aka Newcastle), to try to make good their predecessor’s error. For the moment, Don Share’s often postponed – or prorogued – edition of the Collected Poems is again slated to appear with Faber, now in 2015: I wish it could have been backdated.

A good deal of my argument and probably everything I’ve quoted (and there could have been much more) is taken from A Strong Song Tows Us. So is it a case of ‘there are the Alps,/fools! Sit down and wait for them to crumble!’? Not quite. It’s a tremendously diligent and feisty and energetic biography, but has done little to change or educate my sense of Bunting, beyond the work of Burton’s much slighter predecessors, Victoria Forde, Richard Caddel and Carroll Terrell. An ideal biography, a deliriously wonderful biography as I hoped this might be, is somehow of a piece. This one seems to use back-projection: our hero is kept dimly in the foreground, while things are described happening behind him – Quakerism, education, fascism, Eliot, Persian politics, the North. It means we are left short of real interaction, presence, behaviour, sense of lived life. What behaviour there is is apt to be problematic: did Bunting actually, as he claimed, scoop a lady’s ‘exuberant bosom out of its corsage’ instead of kissing her hand, or is that another story? Burton can be hectoring (‘one of the great love stories of the 20th century’, ‘some of the finest critical minds of the century’, ‘arguably the world’s most celebrated living poet’, ‘two of the greatest poems of the 20th century’, ‘the most exquisite meditation on meditation of the 20th or possibly any other century’; all in the first ten pages of the introduction), a little indiscriminate in his quoting; and has a tendency to get involved in something and not settle it (did the young Bunting kick a policeman in the pants, or did he actually bite him on the nose? We’re not told, but we get to hear all about both versions). He pays lip service to Bunting’s personal opposition to biography and study and ‘meaning’ and goes so far as to borrow the five parts of Briggflatts for his narrative structure; he might more usefully have told himself to hang it all, Sordello, this is a biography and I’m going to break eggs. (This also has the perversely unintended effect of seeming not to leave a single poem of Bunting’s unmined for biographical information.) It’s not as though Burton won’t defy Bunting in other respects; ‘Bunting absolutely loathed this kind of [literary-critical] analysis,’ he writes, with a kind of worried complacency. I would have liked a little less of it and more on Bunting and difficulty, or Bunting on authority. Difficulty is other people; or is it authority is other people? For someone who professed to be almost allergic to artistic society, he traded a great deal on who he knew. He may only have had three or four readers for much of his life, but he knew their names, and made sure we do too (Yeats knew one of Bunting’s odes, ‘I am agog for foam’, by heart). I remain unsure about his scholarship and his ability with languages. Is his Latin translation of Zukofsky good Latin? Bunting’s ties to home – a vital subject, given how much of his life he spent abroad – and perhaps the London establishment in general, are left shadowy. Was there no ladder for him, or was he just not interested in climbing it? It’s odd to read of him submitting an article on Spanish politics to the Spectator while stuck on Tenerife, for instance. He doesn’t seem to have been that sort of industrious chancer.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.