Ahousing shortage that has been building up for the past thirty years is reaching the point of crisis. The party in power, whose late 20th-century figurehead, Margaret Thatcher, did so much to create the problem, is responding by separating off the economically least powerful and squeezing them into the smallest, meanest, most insecure possible living space. In effect, if not in explicit intention, it is a let-the-poor-be-poor crusade, a Campaign for Real Poverty. The government has stopped short of explicitly declaring war on the poor. But how different would the situation be if it had?

Look at things from Pat Quinn’s point of view, for instance. What’s being done to her is happening quite slowly, over a period of months, and is not the work of a gang of thugs breaking down her door and screaming in her face, but is conducted through forms and letters and interviews with courteous people who explain apologetically that they’re only implementing a new set of rules. At the age of sixty, having worked for thirty years before being registered as too unwell to work, Pat Quinn is effectively being told that she’s a shirker, and that the two-bedroom council flat where she’s lived for forty years and where her husband died is a luxury she doesn’t deserve. She’s been targeted for self-eviction. Essentially, the government is trying to starve her out. Without the government allowance she receives in the form of housing benefit, she cannot pay her rent, and the government has cut the allowance so it’s no longer enough to cover the rent on a two-bedroom council flat. It’s just enough for a one-bedroom flat – a theoretical, but actually non-existent, one-bedroom flat. This is what the ‘bedroom tax’ means.

‘It’s just very, very hard to deal with,’ Quinn told me when I visited her. ‘This is my home, this isn’t just a council place where I live. They can only do it to me because I have nothing. I’m sure if they had their way they would kill us. I really believe that.’

It wouldn’t be so tough on Quinn if her municipal landlord, the borough of Tower Hamlets in East London, or one of the local housing associations – not-for-profit groups offering low-rent homes – or their counterparts in neighbouring boroughs, or the private sector, had affordable one-bedroom flats to spare. They don’t. As I write this, the cheapest one-bedroom private flats in Quinn’s area cost £240 a week including council tax, at the very edge of the new maximum the government is willing to subsidise for a single person. Demand is intense – they don’t stay on the market for more than 48 hours, as a rule – and since, under the new rules, housing benefit will be given to the tenant rather than directly to the landlord, private landlords will be warier than ever of letting to benefit claimants.

The old council house waiting list no longer exists. Now areas run waiting lists for ‘social housing’, a pool of council and housing association properties at subsidised rents. In Tower Hamlets, there are 22,000 people on the list. A significant number of them will have families, so it’s hard to know how many individuals the figure represents, but it corresponds to a fifth of all households in the borough. Of this 22,000, 10,000 are waiting for a one-bedroom flat. Five hundred of them have been waiting 12 years or more. How many one-bedroom flats became available in Tower Hamlets in 2012-13? Just 840. Supply and demand have floated free of each other, and not only in the category of social housing. In the same year, the price of private flats for sale in Tower Hamlets went up by 5 per cent; in neighbouring Hackney, which has a similar demographic, it was a wild 15 per cent.

There aren’t enough homes in Tower Hamlets. There aren’t enough homes in London, in the South-East, in Britain. The shortage gets worse. Each year, population growth and the shrinking of average household size adds a quarter of a million households to the 26 million we have now. The number of new homes being built is barely above a hundred thousand.

To understand how it came to this, you have to go back to 1979, when Margaret Thatcher began forcing local authorities to sell council houses to any sitting tenant able and eager to buy, at discounts of up to 50 per cent. It was one of those rare policies that still seems to contain in its very name the entire explanation of what it means: ‘Right to Buy’. Cherished by Tories and New Labour alike as an electoral masterstroke, it offered a life-changing fortune to a relatively small group of people, a group that, not by coincidence, contained a large number of swing voters.

Right to Buy differed from the period’s other privatisations in many ways. It was tightly linked to the buyer’s personal use of the asset being privatised. If the Royal Mail had been sold on the same principle buyers would have got a discount on the share price based on the number of letters they’d posted over their lifetime. According to Hugo Young, Thatcher had to be talked into Right to Buy by a desperate Edward Heath, then her leader, who’d been persuaded by his friend Pierre Trudeau after his electoral defeat in February 1974 that he needed a fistful of populist policies. No wonder Thatcher baulked. Right to Buy violated basic Thatcherite values: that self-reliance was good, state handouts bad. Right to Buy was a massive handout to people who weren’t supposed to need handouts. In fact, that was why they got the handout – because they were the kind of people who didn’t need handouts.1

It was Britain’s biggest privatisation by far, worth some £40 billion in its first 25 years. But the money earned from selling Britain’s vast national investment in housing – an investment made at the expense of other pressing needs by a poor country recovering from war – was sucked out of housing for ever. Councils weren’t allowed to spend the money they earned to replace the homes they sold, and central government funding for housing was slashed. Of all the spending cuts made by the Thatcher government in its first, notoriously axe-swinging term, three-quarters came from the housing budget.

What you think the Thatcherites expected to happen once they’d set Right to Buy in motion depends on how cynical you are about their motives. The most benign view is that they thought supply and demand was a straightforward elastic law, and that the market would take up the slack: private housebuilders would build more homes, for both sale and rent, as the number of new council houses being built waned. A dwindling number of the poorest people would be catered for by residual council stock, by the non-profit housing associations – which would still get state grants to build houses for the less well-off – and, for those who were really hard up, by an obscure welfare top-up called housing benefit.

It didn’t happen that way. One outcome can be seen starkly in a recent online manifesto for self-builders of private homes, A Right to Build. Published in 2011 by Sheffield University’s school of architecture and the London architectural practice 00:/, it was designed as an attack on the dominance of the big seven private housebuilding companies – in descending order of size, Taylor Wimpey, Barratt Homes, Persimmon, Bellway, Redrow, Bovis and Crest Nicholson – who between them have almost 40 per cent of the market in new homes. But the most striking thing in the document is a chart displaying the history of Britain, in housebuilding and house prices, since 1946.

It shows that in the 1980s, as the construction of new council houses shrank to almost nothing, there was a slight rise in the number of private homes being built, peaking at around 200,000 homes a year at the end of the decade. Then it fell back – and stayed fallen. Between the early 1990s and the onset of the financial crisis in 2008, supposedly a boom time in Britain, the number of new private homes built each year didn’t go up. It barely budged from the 150,000 a year mark. The market failed. There was increasing demand without increasing supply. Mid-boom, as the imbalance between the number of people chasing a house and the supply of new homes reached a tipping point, average house prices took off like a rocket, trebling between Tony Blair’s accession and the 2008 crash. (In Tower Hamlets, prices went up three and a half times.) Even allowing for inflation over that period of time (36 per cent) it’s a terrifying increase.

The chart only shows part of Right to Buy’s drawbacks. Those tenants who didn’t buy their houses, either because they didn’t want to or because they couldn’t afford to, had their rents jacked up. At the same time, because of the growing shortage caused by the inability of councils to build, the failure of private builders to build enough, and weak government support for housing associations, rents in the private sector went up. The poorest and most vulnerable members of society, the sick, the elderly, the unemployed, single mothers and their children, were shared between a shrinking stock of council housing – the council housing least likely to be sold, that is, the worst – and the grottier end of the private rental market.

Much of the rent in both types of tenure had to be covered by housing benefit, and as council houses continued to be sold, the proportion of the poor and disadvantaged claiming housing benefit in expensive privately rented property rose. Many people who bought their council houses sold them on to private landlords, who rented them to people on housing benefit who couldn’t get a council house, at double or triple the levels of council rent.

Right to Buy thus created an astonishing leak of state money – taxpayers’ money, if you like to think of it that way – into the hands of a rentier class. First, the government sold people homes it owned at a huge discount. Then it allowed the original buyers to keep the profit when they sold those homes to a private landlord at market price. Then the government artificially raised market rents by choking off supply – by making it impossible for councils to replace the sold-off houses. Then it paid those artificially high rents to the same private landlords in the form of housing benefit – many times higher than the housing benefit it would have paid had the houses remained in council hands.

In other words, since Thatcher, the British government has done the exact opposite of what it has encouraged households to do: to buy their own homes, rather than renting. Thatcher and her successors have done all they can to sell off the nation’s bricks and mortar, only to be forced to rent it back, at inflated prices, from the people they sold it to. Before Right to Buy, the government spent a pound on building homes for every pound it spent on rent subsidies. Now, for every pound it spends on housing benefit, it puts five pence towards building.

The response of the current government to the housing crisis is to try to make it worse. It is taking steps to increase house prices, without taking steps to increase supply. The coalition’s two most explicit interventions in the housing market have been to restrict supply and raise prices: the first when it cut, by two thirds, the grant given to housing associations to build new homes, and the second with its mocking parody of Right to Buy, ‘Help to Buy’, offering already well-off people cheap loans to overbid for overpriced houses they couldn’t otherwise afford.

Those who believe the aim of Britain’s private housebuilders is to build as many homes as possible, and that they are only prevented from doing so by a cranky planning system, could say I’m being unfair and point to another coalition intervention. In 2012 the old rules governing what could get built where were replaced with a streamlined model called the National Planning Policy Framework, NPPF, which put the onus on councils to allocate enough land for new houses – including farmland, if necessary – to meet demand five and a quarter years ahead. Councils who don’t comply face, in theory, being overruled on appeal if they try to stop speculative development. But putting aside land for houses isn’t the same as building them. The historical evidence suggests Britain’s private housebuilders have been driven less by the urge to build the maximum number of new homes than by the urge to make as much (or lose as little) money as possible.

Pat Quinn was born into the final waning of the old East End, where working-class Londoners rented rooms in cramped, crowded, badly maintained terraced houses with poor plumbing and sanitation. Aged twenty, just married, Quinn and her husband, like hundreds of thousands of others, swapped their private landlord for a tenancy with the state. Long before the Luftwaffe and Hitler’s V-weapons knocked jagged holes in the soot-blackened brick of Bethnal Green, Stepney and Poplar, the three London boroughs that would eventually be merged to create Tower Hamlets, the muncipalities had begun knocking down old streets and moving their residents into newly built council houses, bigger and lighter than anything they were used to, with modern kitchens and indoor lavatories. When the Second World War was over, the bulldozers returned to clear bombsites and slums all at once, and the construction of new homes went on.

The pattern was repeated across the country. There was a difference, however, between council houses built in the 1920s and 1930s and those built after 1945. The interwar municipal housing estates were focused on the poor, on replacing the worst slum housing, even though, in practice, the poorest of the poor could seldom afford the rents, and moved to another slum instead. The politicians who got the interwar houses built were motivated by the fastidious, paternalistic, missionary zeal of their 19th-century reformist forebears, together with a contrary mixture of fear that socialism would come (so we’d better show the workers that a capitalist society cares) and hope that socialism would come (and this is what it will look like).

After 1945, as the scale of council house building increased in the hopeful atmosphere of the budding welfare state, the builders’ masters voiced more ambitious aims. In 1946, Aneurin Bevan, minister for both health and housing, told Parliament that having the better-off catered for exclusively by speculative builders while the poor were set apart in council housing was wrong.

You have castrated communities. You have colonies of low income people, living in houses provided by the local authorities, and you have the higher income groups living in their own colonies. This segregation of the different income groups is a wholly evil thing, from a civilised point of view … It is a monstrous infliction upon the essential psychological and biological one-ness of the community.

Bevan’s stance had all sorts of implications, but the most significant was that there was no limit to the number of houses the state was prepared to build, that building would continue until there was a home for everyone – a point effectively reached in the 1970s, at about the time Quinn and her husband moved to their new council flat.

Until then Quinn and her parents – father a long-distance lorry driver, mother a worker at the Bryant & May match factory – had rented the downstairs floor of a private terraced house in Usher Road, Bow, a land of cobblestones, cigarette smoke, crowded pubs and crowded bedrooms, backyard privies and tin baths filled with water heated on the range. Usher Road was the kind of place the authorities considered a slum, and it was decided to knock the old terraces down. Residents were offered a choice of council house. Quinn chose a flat in a small new block near the Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel, two miles closer to the centre of London. Her husband was sceptical – Whitechapel had a reputation as a rough area where the sex trade flourished – but he went with her choice and they settled in. It is a measure of the relative value of private and council rentals in those days that their rent went up from £1 a week to £4.

I met her at a public meeting in Bethnal Green called to discuss ways of combating the government’s welfare changes and went to visit her at home a few weeks later. Her flat is one of ten in a plain, red-brick, three-storey block; five one-bedroom places on the ground floor and five two-bedroom flats on the upper storeys, one of which is Quinn’s. It was summer and red and white roses were blooming in the block’s communal gardens. Quinn showed me the fruit and vegetables the residents had planted in the spring: raspberries, strawberries, lettuce, onions, peas, beans, radishes. ‘Very optimistically a gentleman is trying to grow kiwis,’ she said. ‘The cherries aren’t quite ripe enough to give you one … there’s an aubergine there but I don’t think it’s going to make it.’

Only three of the ten flats still belong to the council. The rest have been sold off. Four are lived in by their owners and three are let out privately. Students share one of the flats, and in the others there are bankers (the flat is two tube stops from the City; you could walk to the Lloyd’s building in half an hour), an immigration lawyer and an accountant working in one of London’s temples of public art. ‘Irish, Welsh, Iraqi, Bengali … three Bengalis. And myself, English,’ Quinn said. It’s the sort of diversity that might have pleased Bevan. But the government wants Quinn out.

In the 1990s, Quinn was officially recognised as too sick to work as the result of a bundle of ailments (she lists them: joint pain, migraines, gastritis, bouts of depression, underactive thyroid) and since then has had her rent and council tax, currently £120.39 a week, covered by housing benefit. For living expenses, she received £112 pounds a week in incapacity benefit. (The Joseph Rowntree Foundation reckons £200 a week, excluding rent, is needed to maintain a decent life.) But last spring, everything changed. The bedroom tax – which effectively fines Quinn for losing her husband – slashes her housing benefit to £97.15 a week, leaving her to make up the £23.24 difference out of her incapacity payment. Except now she’s not getting that either. At the same time she was hit by the bedroom tax, she was called in for a medical to reassess her fitness for work under the government’s new, tighter incapacity rules. The assessment consists of ten checks on physical ability, such as:

Can you move more than 200 metres on flat ground? (Moving could include walking, using crutches or using a wheelchair.)

Can you usually stay in one place (either standing or sitting) for more than an hour without having to move away?

If you experience fits, blackouts or loss of consciousness, do they happen less than once a month?

Then there are ten checks on your ‘mental, cognitive and intellectual functions’: ‘Can you deal with people you don’t know?’ or ‘Can you usually manage to begin and finish daily tasks?’

Each check answered ‘no’ scores points. The more points you get, the more likely you are to continue to be recognised as disabled. Quinn got zero points and a message telling her that the government accepted she was ill, but that she was not ill enough: she would have to start looking for work, and as long as she was unemployed, she would be switched to the Jobseekers’ Allowance – a cut in the money she lives on of 40 per cent, down to £72 a week. But because of the bedroom tax, £23.24 of that has to go towards her rent, leaving her with just £48.76 a week to live on; £22 comes out of that for gas and electricity, which leaves about £27 a week for everything else. She doesn’t drink, she doesn’t smoke, she doesn’t go to the bingo, she doesn’t have a car, but that £27 pounds has to cover the TV licence and her phone, as well the dozens of small items everyone needs, like toothbrushes and soap and light bulbs and postage stamps.

And food.

Britain’s ever helpful banks have contributed to the picture. They have permitted Quinn to build up a debt of £6000 on three credit cards. ‘It’s a nightmare,’ she said. ‘I had to apply for crisis loans. I haven’t paid the rent, the electric or the gas. At my age it’s embarrassing to be in this position.’ It wasn’t that she didn’t want to work, she said; she left school at 15, on a Monday, and got a job on Tuesday. She does unpaid volunteer work as a local health champion. ‘I can’t do the heavy stuff. I’m not saying I can’t work at all but they want you to work a full 40-hour week. They should prepare you for work and find out what you can do, instead of saying you’ve got to be prepared to work from now, without any preparation or anything.’

She will get a state pension, but not until November 2015. If she can hang on to her flat until then she’ll be exempt from the bedroom tax. But it isn’t clear how she will survive in the meantime. ‘I think there should be a fairer way of asking people to leave their accommodation,’ she said. Council tenants face a jail sentence if they try to sublet. I asked Quinn if a relative could move in so as to avoid the bedroom tax. ‘That defeats the purpose of having a second bedroom,’ she said. ‘Why shouldn’t I have a home I don’t have to share with anyone? I could have my granddaughter move in. But if I had her, my daughter would have to give up the family credit. There’s a way round it but somebody else has to lose money.’

One of the curious things about Quinn’s situation is that the government would love to give her £100,000, but she’s not prosperous enough to qualify for it. That figure is the maximum discount on the market price a council tenant who exercises Right to Buy can now claim in London. Given that her flat would be worth at least £300,000, Quinn could, in theory, buy it, sell it on and pocket the difference. But then she’d have nowhere to live; and she can’t raise the missing £200,000, because she has no money for a deposit and no way of getting a mortgage. She and her husband didn’t have a principled objection to Right to Buy. They just never got rich enough to get richer.

In most people’s understanding of the world I’d be considered a homeowner, although since I have a mortgage I am, for the time being, renting it from the bank. I was born at my grandparents’ house in Blackheath in the middle of the great London smog of December 1962, and since then I’ve had about thirty different homes: private flats my parents rented in London, a housing association property in Nottingham, state-owned homes in Lanarkshire during my father’s years working for the Scottish prison service, a council house in Dundee, then a private terraced house there (the first home my parents owned, bought when they were in their early thirties), student digs in Edinburgh and London, private rentals in Northampton, a flat of my own in Edinburgh bought when I was 27, various rentals in the Ukrainian equivalent of privatised council flats, residency in Moscow apartments belonging to Russia’s Diplomatic Corps Administration, two floors of a Georgian terraced house in North London bought with my then wife, a post-divorce rental in the East End, and now, my third tilt at home ownership, a flat in a converted school in Bethnal Green (Pat Quinn’s old school, as it happens).

I don’t expect to find myself living in a council house in the traditional sense – that is, a household dwelling owned and run by the state – any time soon. But that’s more to do with the shortage of council houses, and the way they’re run, than with any objection on principle, or a conviction that council houses are doomed to be ugly and uncomfortable. None of the things tenants found repellent about life on some council estates in the 1970s – the crime and anti-social behaviour, the damp, the powerlessness in the face of council bureaucracy, the noise, the distance from children’s playgrounds, the difficulty of imposing personal style on a habitat you didn’t own, the penny-pinching bodgery of council repairs, the obstacles to moving – is inherent to municipal tenure; they’re the result of incompetence, carelessness and unreasonable economies.

Councils made some terrible mistakes in their postwar housebuilding programme, partly because of pre-Thatcherite Conservative populism. The Tories started a race with Labour over who could build more houses, abandoning Bevan’s conviction that numbers weren’t enough, that the homes had to be spacious and well built, too. The worst blunder involved the use of a Danish system of prefabricated concrete panels to build tower blocks three times higher than they were designed to be, assembled by badly supervised, badly trained workers and engineers. Hence the Ronan Point disaster in 1968, when a 22-storey block in East London partly collapsed after a gas explosion, killing four people. The block was finally demolished the year before the great storm of 1987, which might literally have blown it down. Ronan Point was designed to withstand winds of up to 63 miles per hour; some of the gusts during the storm reached 94 mph.

As the decades pass and the council homes of the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s grow into the urban landscape, as their brick and concrete weathers, as they benefit from comparison with the mean little boxes being built by private housebuilders, as a mix of new management, new investment and funds from the last Labour government have dealt with some of the backlog of repairs and design flaws, as the original intentions of architects become unexpectedly visible to a new generation, they are beginning to look like more attractive places to live. Too late for the less well-off; just in time for the hipsters. Rural peers now snap them up for their London pieds-à-terre. Wealthy parents buy them for their children. Buy-to-let investors cram them with students. I might have bought one myself, to live in; friends have done so. Once privatised there was no chance of the councils getting them back. I was shown plenty by estate agents in Tower Hamlets when I was looking for a place to buy – the agents call them ‘ex-local’, as in ‘ex-local authority’. They were among the few places of any size I could afford, and they still sell for slightly less than homes built for the market. This is unlikely to last. In the capital, council houses have gone vintage; council houses in inner London are the new lofts, to be boasted about and refitted with salvaged Bakelite and Formica by the trendiest of their new inhabitants. In addition to all the other indignities the poorest of the poor in London suffer, they now have an extra one: the implication that they never saw the potential.

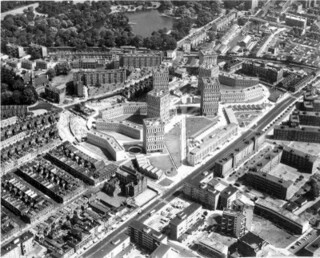

From my window, council houses – many of them privatised – are what I see. On the far side of Roman Road are the barracks-style brown brick walkways of the Greenways estate, built in the 1950s, solid and unremarkable, renovated not long ago, providing homes for hundreds; beyond them, its crown poking up beyond the Greenways roof, is Denys Lasdun’s listed Sulkin House, built on the site of a bombed church, twin stacks of council maisonettes at an angle to each other, linked by a central, cylindrical shaft, like an open book propped on end – an early attempt to create a vertical street. But the main vista is on an altogether more epic scale, an inhabited 20th-century Stonehenge, a 17-acre site of six towers and five lower blocks, widely spaced apart and angled in such a way that at least one face will always be catching the sun and the shadows cast by the towers will rotate like the spokes of a wheel. This is the Cranbrook Estate.*

Cranbrook calls attention to itself. It’s startlingly different from other estates. The piloti – stilt-like struts cut in from the building’s outside edge at ground level – of the high towers are shared with Le Corbusier’s modernist étalon, the Marseille Unité d’Habitation (which is smaller), but the most striking feature of the blocks, to the non-architect, are the superfluous details that depart from Le Corbusier’s functional modernism: the flying cornices, concrete frames like giant handles that jut from the tower roofs, and the frog-green bosses studding the beige brick façades. The initial effect is of some vast, elegant set of combination locks, or duochrome Rubik’s cubes, poised at any moment to whirr and counterspin, floor by floor, to trigger the catch on some deeper, hidden secret. Yet familiarity humanises it. You become aware not only of how soaked in light it is but of the architects’ legacy to the people who live there. Close to Roman Road is a crescent of red brick bungalows for the elderly, grouped around a garden with a fountain and a bronze sculpture by Elizabeth Frink, The Blind Beggar and His Dog. The toylike bungalows are superficially so different from the beige and green high rises behind them that you might assume they had nothing to do with each other, yet they were part of the plan from the start.

The architects hired by the then Bethnal Green Council for the project, built between 1955 and 1966, were the trio of Francis Skinner, Douglas Bailey and an elder mentor, the legendary bringer of the torch of modern architecture to Britain from Europe, Berthold Lubetkin. There’s a received idea that Lubetkin was only peripherally involved in the design of Cranbrook. He was living in rural Gloucestershire, where he’d been based ever since evacuating his family there in 1939, farming pigs and brooding over the collapse of his hopes of becoming the master builder of a new town for coal-miners in Peterlee, County Durham. Yet as his biographer John Allan has shown, Lubetkin didn’t step back from his vocation till much later.2 Indeed, he was responsible for the overarching design of Cranbrook. Each month he would come up to London, sketchbook bulging with plans.

Lubetkin and his protégés, backed by the public purse of Bethnal Green and London County Council, make an easy target for haters of publicly subsidised housing, for haters of the experimental in architecture, and for those more nuanced sceptics who believe with great passion in state housebuilding but condemn the execution of the great concrete monuments of residential modernism. The argument is that councils treated their tenants like factory-farmed livestock, stacking them on top of one another in concrete boxes in defiance of their traditional British desire for two-up, two-down homes with a patch of garden; that they left them prey to the visions of egotistical architects, who thought only of the grandiose shapes they would carve in concrete, shapes they would never imagine themselves inhabiting, or their children, or anyone they knew. There’s much truth in this. In her book Estates (2007) Lynsey Hanley, who was brought up on a council estate on the edge of Birmingham, mocks architectural critics who describe various notorious London council tower blocks as inspiring ‘a delicate sense of terror’ or ‘incredibly muscular, masculine, abstract structures, with no concession to an architecture of domesticity’.

‘After all,’ Hanley remarks, ‘domesticity is the last thing you need when you have a family to raise.’ The professional avant-garde’s take on residential modernism, she argues, ‘seems to fall for the idea that housing should be art. It ought to be beautiful, yes, but not at the expense of the people who have to live in it.’ She doesn’t explicitly mention the work of Bailey, Skinner and Lubetkin in Bethnal Green, but Lubetkin and his work on Cranbrook would seem, on the face of it, to conform to her archetype of the selfish modernist. Her critique is from the democratic left, but the legacy of Lubetkin and Cranbrook could just as easily be damned by conservative aesthetes in the mould of Prince Charles as having yoked the English working man to alien, totalitarian forms of dwelling.

Lubetkin, who died in 1990, gave his critics plenty to work with. He did have an ego; he deployed his enormous intellect with more force than tact. He and his wife, Margaret, were lifelong communists, and his early designs for Cranbrook were sketched under the influence of a trip he had made to his native Russia in 1953, after the death of Stalin, where the superhuman scale of state planning’s achievements thrilled him:

The broad expanse of the Volga drawn into the composition of rebuilt Stalingrad by a wide cascade of gigantic granite steps; the huge stadium which seems as broad as it is long; the ribbon of the Volga-Don canal in the midst of the arid steppe, with its sparkling foaming sluices; the generous openness of the forecourts and parks on which the new university building is presented to old Moscow, where the limitless parklands merge with the sky, and the horizon, as at sea, is imperceptible; these are sights that no architect who has been fortunate enough to see them will easily forget.

In reality, Lubetkin was too idiosyncratic to be a modernist, too liberal to be a Stalinist. Far from being a harmonious and cynical collaboration between municipality and architect, the Cranbrook Estate bears the mark of Lubetkin’s despair at Bethnal Green and the London County Council, for which housebuilding had become a numbers game, in which architectural vision and the sense of building a better world for working people had shrunk to sheaves of norms, regulations and pro formas – the first signs of an entry point for the privatisers (Harold Macmillan coined the phrase Right to Buy in the 1950s). Lubetkin had been thwarted in his desire to ally his ego and talent to progressive causes ever since he arrived in Britain from Paris in 1931. His early commissions were private flats for the wealthy and zoo buildings, including the extant penguin pool at London Zoo. Only for a brief time, when he worked with Finsbury Council in mid-century, did he come close to what he wanted: to listen attentively to the needs of residents and workers, then interpret their commission in his own way, with the support of secure, trusting patrons. Even then he was hobbled by postwar parsimoniousness.

When Lubetkin first expounded his vision for Cranbrook to his council patrons, he started with medieval metaphysics and moved through to the Enlightenment via Copernicus, Descartes and Tintoretto. Was this the ludicrous self-importance of a man out of touch with working-class realities, or the sense of responsibility of an artist-craftsman who, despite his disillusionment, couldn’t but take seriously the job of building homes for more than five hundred families? I prefer the second version. These were the days when councils’ idea of consultation with future residents was to find out how many bodies there were and produce a piece of paper for the architect called a ‘surrogate briefing’ which listed the number of units required to put them in. Seen in that light the secret message of Cranbrook, its stand-out otherness, the sense it offers to the passer-by that whoever was responsible for it was striving with unusual mental ferocity to realise some obscure and arcane task that he considered incredibly important, is exactly the sign Lubetkin and his collaborators wanted to draw. A sign that read ‘No council block must be just another council block’; a sign that read ‘This matters.’ He doubted even then whether it would be read. Towards the end of his life, he’d come to feel, he told Allan, that

the public themselves became more and more disillusioned with any idea that art or architecture could lift them up or foreshadow a brighter future. Instead of looking at architecture as the backdrop for a great drama – the struggle towards a better tomorrow – they began to see only the regulations, housing lists, points systems, et cetera, and so expect only ‘accommodation’ … it made all our efforts seem so hollow.

Doreen Kendall was one of the original tenants of Puteaux House, one of the tower blocks on the Cranbrook Estate, completed in 1964. She’s lived there ever since, in a two-bedroom, two-storey flat on one of the high floors; she and her late husband raised a daughter there. The common parts of Puteaux House are a little down at heel but the spaces are generous and light. Looking up from the lobby you can see the teardrop cross-section of Lubetkin’s stairwell stretching up to the heights. In the early days children used to slide down the bannisters non-stop from the 15th floor to the ground. There’s an intimacy and a familiarity within this vertical community. When I visited, we could hear somebody vacuuming the floor of the flat upstairs. ‘She does all the corners every Friday,’ Kendall said.

With their discount and an inheritance, the Kendalls were able to buy their flat in 1984. Rents had been going up and they thought they’d have a more powerful voice in dealings with the council if they became leaseholders. On the estate as a whole, about a third of the flats are in private hands. Kendall was astonished when I told her that councils had been forced to use the money they got from Right to Buy to pay down their share of the government’s general debt. ‘I thought it was in a pot, waiting to be used again,’ she said. ‘I thought there was a housing account that everything went into and they were just waiting for the government to release it.’

One by one, the original Right to Buyers are checking out of Cranbrook. ‘There’s about 15 that have bought and they’ve died off and the flats’ve been sold. Arthur downstairs died over Christmas, and his flat’s for sale. Sonny over in Offenbach, he died just before Christmas and his flat’s up for sale. They’ll be bought by people to be relet on short tenancies. You get to know people, they’re very nice, then all of a sudden they’re gone.’

Kendall is a fisherman’s daughter, born in Milford Haven in 1929, who got her school leaver’s certificate and moved from Pembrokeshire to the eastern edge of London to stay with her aunt and look for work. There she met John, a tailor in Bethnal Green, and moved in with him to a private rental in the East End. They were offered a place on the Cranbrook Estate after their old house was demolished.

The standard left-progressive history of what happened in Bethnal Green is that democratically elected, enlightened municipal authorities rescued the poor citizens of the borough from insanitary, crowded slums and gave them modern, healthy places to live at a reasonable rent, places that often delighted their new tenants, before institutional neglect, competitive consumerism and budget cuts took the shine off estate life. But there’s an alternative, subversive account, which suggests that at some point – perhaps the 1950s, perhaps even earlier – ‘slum clearance’ began to merge into something else, the needless destruction of fundamentally sound old terraced houses which councils could have bought and modernised.

Kendall, who happens to be secretary of the East London Historical Society, subscribes to both versions of events. She and her husband adored the old two-room private flat they rented in St Peter’s Avenue, and fought a long, bitter and unsuccessful battle with the council to prevent it and the neighbouring homes being knocked down. ‘It was a lovely house,’ she said. ‘These days they would have done them up because when you go down Columbia Road the houses aren’t as nice.3 It had a huge old garden. The toilet was just outside the back door. It didn’t worry us. It had shutters and brass fittings – it wasn’t a slum. We were absolutely heartbroken when they cleared the houses from there.’

Rather than seeing the move from St Peter’s Avenue to the Cranbrook Estate as an expulsion from Victorian East End Eden to concrete council tower block hell, however, Kendall embraced her new home with the same fervour. ‘I loved it,’ she said. ‘I absolutely adored it. We had central heating so we didn’t need to light a fire any more. My husband thought we’d moved into a ship. All the walls were painted grey, battleship grey. Everything was grey except the wall where my books are and the bathroom, which was red, a dusty red.’ The Kendalls avoided the alienation from the familiar rhythms of the city experienced by other East Enders who moved out to suburban council estates. ‘You knew everybody anyway because you’d moved in with them. It wasn’t a case of making new friends.’

Kendall pointed to the armchair where I was sitting and told me Lubetkin had sat in that very place, asking how she liked her new digs. I was sceptical: perhaps it was Skinner, or Bailey? But Kendall insisted it had been the old man himself, strong Russian accent and all. ‘I always had the impression that he was the boss. We all used to come, all the mums, and meet him and he’d say: “How’s things working?” He’d come in and have a biscuit and a cup of tea and he’d say that no matter what flat he went into, his décor went with the furniture. He was very proud that everything went together.’

What Kendall has taken from the ruins of her previous home is a determination not to let the authorities mutilate the grandeur and pleasingness of her habitat a second time. She pointed out all the ways the council has departed from Lubetkin and his partners’ design. The blocks used to be heated from central boilers, but these were shut down and replaced by individual boilers for each flat; as a result ugly white pipes now hang off the towers, like sheets knotted together by escaping prisoners. Originally the façades of the towers were cut into by deep openings that left the broad hallways between flats open to the air and gave Kendall a view of St Paul’s Cathedral; after the 1987 storm, the council replaced them with blank steel shutters that close off the view from inside and, from outside, echo the bleak appearance of a row of shuttered shops. The green bosses studding the façades of the towers were originally made of concrete faced with glass beads that glittered in the sun; the council replaced them with aluminium boxes. Now when it rains, residents are driven mad by the sound of the drops rattling on the metal. The Historical Society’s repeated efforts to get Cranbrook listed have been rebuffed. ‘The council doesn’t realise what wonderful buildings they’ve got here,’ Kendall said. ‘We’re just the Cranbrook Estate.’

Lubetkin’s last artistic statement to the world was his finishing touch to the estate. In his vision, a broad, tree-lined pedestrian boulevard was to lead from Roman Road through Cranbrook to the great open space of Victoria Park. The boulevard exists, but the council refused to buy the last sliver of land blocking Cranbrook from the park’s chestnut trees and ornamental lake. Lubetkin filled the melancholy dead end that resulted with a trompe l’oeil sculpture of a ramp and receding hoops, which, as you approached it, seemed to take you towards some mysterious, hopeful future point. It’s gone now; the council failed to maintain it. When I saw her, Kendall had just had a circular from the council announcing a new initiative to give children ‘a sense of ownership’ of the estate by encouraging them to express themselves freely with paint on the walls around the old sculpture. The project was to be called ‘Bling My Hood’.

In 1963 the anarchist housing writer Colin Ward took a walk through Bethnal Green. He saw one of Denys Lasdun’s new council blocks, admired Britain’s first ever large-scale council housing, the handsome, Hanseatic-looking Boundary Estate, and saw the demolition of the area’s first great effort at philanthropic housing, the gloomy Victorian model workers’ tenements of Columbia Square, funded by Baroness Burdett-Coutts under the badgering of Charles Dickens. The square was being knocked down to make way for another Bailey, Skinner and Lubetkin project. Ward saw temporary wooden housing, the ‘prefabs’, some old enough to have gardens round them, some new. Bethnal Green’s prefabs were, Ward wrote, ‘simply the latest, temporary exhibit in what is not only a sociologist’s zoo, but an architectural museum. It’s all there, every mean or patronising or sentimental or brutal or humane assumption about the housing needs of the urban working class.’

Bethnal Green is still an architectural museum, or perhaps, now that Tower Hamlets is officially Britain’s fastest growing borough, an architectural gallery, a showroom for housing policies.4 New housing versions emerge. Converted schools. Converted churches. Converted synagogues. Converted hospitals. Since Pat Quinn moved to Whitechapel the match factory where her mother worked has been turned into private flats. The factory’s old water tower was the platform from which the army proposed to shoot down airborne threats to the 2012 Olympics, which were held a mile from Quinn’s old house. The borough teems with estate agents. Private developers are building and marketing flats along the Tower Hamlets stretch of the Regent’s Canal – which not that long ago was a derelict, post-industrial, don’t-go-there-after-dark place – as if the canalfront were the Côte d’Azur. And yet there are still an awful lot of poor people living here, old, sick, unemployed or just badly paid, in the economic shadow between London’s two financial districts, the City and Canary Wharf. As everywhere in the South-East, there is a huge, growing, unsatisfied need for housing that doesn’t require you to earn an above average income to afford. With the original council housing stock still dwindling and not being replaced, how is that need going to be met? One possibility is that slums will come back. Already 40 per cent of homes let at below market rents in Tower Hamlets are officially classed as overcrowded. Tower Hamlets has been less forthcoming about overcrowding in the private sector than its eastern neighbour, Newham, which has proclaimed a crackdown on ‘beds in sheds’, but the problem exists. In 2011 a private landlord was fined £20,000 for ignoring orders from Tower Hamlets to improve two ex-council flats he’d bought and rented out. Each flat had two bedrooms and a living room: the landlord had split each living room in two to create, in all, four tiny bedsits. At one flat he’d tried to expand further by building what inspectors describe as as ‘lean-to’. One of the flats – damp, cold and unsafe, infested with roaches and bedbugs – had seven people living in it. A new fad is ‘rent to rent’, where somebody will rent a flat and then squeeze sub-tenants into the available floor space till they’re making a premium on the rent they pay the original landlord.

Another possibility is that housing associations will come to the rescue. They now let to many more households in England than councils. What are they? And how did so much come to hang on them?

One of the oddest things about the privatisations of water, the railways, electricity and the rest is that they were framed as binary possibilities: stay or go, stick or twist. Those who had a stake in the outcome were either for privatisation, or for the persistence of state ownership. Other forms of organisation weren’t considered. If there were proposals for another way that was neither the nationalised status quo nor stock market flotation, they went unheard. With housing, when Right to Buy came in, an alternative already existed, alongside private and state ownership. Housing associations had existed in various forms since the Middle Ages, philanthropic organisations set up to house the needy. They aren’t always charities, though sometimes they are. Technically they’re both ‘industrial and provident societies’ and ‘registered social landlords’. They’re run on commercial lines – they borrow money at commercial rates, they may build houses for sale or for market rent, they strive to avoid losing money – but they’re forbidden to make a profit, they don’t pay dividends and they don’t have shareholders. Whatever surplus they make is put back in service of their primary function, which is to provide low-rent homes for the less well-off.

Some of the early housing associations are still around: the Peabody Trust, for instance, set up in the 1860s by the Anglo-American businessman and philanthropist George Peabody, which now rents out more than twenty thousand homes in London; and the Joseph Rowntree Housing Trust, which originated in a trust set up by the chocolate-maker in 1904 to administer the model village of New Earswick near York. New Earswick is still there, still offering homes at below market rent. In the 1960s, idealists in North and West London reacted against the slum landlords’ petty exploitations and the demolition-happy dogma of the state. In 1963, Bruce Kenrick – who would a few years later set up the homelessness charity Shelter, just as the nation was absorbing the shock of Cathy Come Home, Ken Loach’s film about homelessness – founded the Notting Hill Housing Trust, which today, as the Notting Hill Housing Association, has 27,000 homes in London. In 1968 the architects David Levitt and David Bernstein and the planner Beverly Bernstein set up Circle 33, now part of a consortium of nine housing associations across England called Circle Housing.

The shift of housing associations away from their philanthropic, idealistic and anarchic roots began in 1974, when the government of a more statist era started giving them grants to build more homes than their modest means would otherwise have allowed. But the transformational step came in 1988, amid the hubris and anti-statist zeal of Thatcher’s radical third term. Right to Buy was faltering; the best-built and most attractive council houses had been sold, leaving councils still responsible for millions of tenants who, lacking the means or desire to buy their homes, continued to live in vast estates that the councils had been starved of the funds to maintain. And because the Treasury had captured the councils’ sales receipts and diverted the rents of their most prosperous tenants to mortgage lenders, the councils lacked the financial muscle to correct, by refurbishment, or demolition and replacement, the design flaws blighting so many estates.

Huge sums were needed to bring these decayed or badly built forests of brick and concrete up to a decent standard. Barring a tax increase, the money could only be got by borrowing, and the stream of revenue from council tenants’ rents made excellent collateral. But the government of 1988 didn’t want to let councils borrow. Partly this was because of a belief that the public sector was incompetent; mainly it was because the sums needed would have to be added to Britain’s total government debt, exposing how the Thatcher-era tax cuts had put the country’s finances in jeopardy. So they turned to the housing associations. First, non-profit making as they were, they were formally designated part of the ‘private sector’, making it possible for them to borrow on the open market without the debt showing up on the government’s books. Then, the government made it possible for councils to sell their housing stock wholesale (or estate by estate if they preferred) to housing associations specially created for the purpose. The only obstacle to a council shedding its municipal housing was a clause, grudgingly added after parliamentary pressure, making it obligatory for tenants to be balloted before a stock transfer could go through.

The first wave of stock transfers was relatively small-scale: mainly rural Conservative councils, starting with Chiltern District Council in Buckinghamshire, which transferred its entire stock of 4,650 houses to the new Chiltern Hundreds Housing Association (still operating today under the name Paradigm). It was under New Labour that the policy took off. Tony Blair and Gordon Brown intended to do the right thing by their party’s natural supporters, the remaining millions of council tenants, and renovate their decaying homes. But they didn’t intend to let Britain’s municipalities take on extra debt to bulk the government’s grants up to the levels required. Pressure was put on councils to offload estates and tenants, and the councils, in turn, put pressure on tenants to vote in favour. ‘Yes’ campaigns got public money; ‘no’ campaigns didn’t. It was made clear to tenants that a ‘yes’ vote would result in money being made available quickly to renovate their homes, while a ‘no’ vote would put refurbishment in doubt. The government spent billions of pounds easing the way for the new housing associations by wiping out the debt attached to the homes they acquired. Council after council went through the process. Glasgow shed its 80,000 council houses; Sunderland disposed of 36,000; in the spring of 2003, Walsall and Coventry sold 43,000 between them. By the end of 2008, there were 170 councils with no council houses left.

In 1985, housing associations ran only 13 per cent of all social housing. The rest were council houses. By 2007, it was half and half; by 2012, only 1.7 million homes were still in council hands, against 2.4 million owned by housing associations. The housing associations seemed the ideal embodiment of Third Way economics, motivated neither by profit nor by state command, a parallel to academies in education and foundation trusts in health, yet with an old and noble pedigree. At a ceremony marking the handover of 17,000 homes in Tameside in 1999, Tony Blair said stock transfers ‘buried for good the old ideological split between public and private sector’.

On the face of it, by ploughing what surplus they make back into building more homes, and doing so, on the whole, with efficiency and respect for tenants, housing associations represent a setback to the prevailing neoliberal consensus that the lust for personal gain embodied in shareholder capitalism is the only deep motivator that can make an organisation succeed. A study by the Joseph Rowntree Foundation in 2009 found that most housing associations which took over and renovated council estates had exceeded the official standards for good homes, in terms of facilities and living space; had given tenants a bigger say in estate management compared to supposedly more democratic councils; and had gone beyond their remit to invest in community facilities like libraries and schools. Lynsey Hanley, who bought a previously privatised council flat on an ugly, decayed estate in Tower Hamlets and became involved in a successful campaign to have the estate transferred to a housing association, knocked down and rebuilt from scratch, wrote:

It’s a testament to the sheer horridness of many estates that their tenants have, like us, elected to have their own homes destroyed in order that something better might replace them, that crime and anti-social behaviour might be designed out and that overcrowded households might finally be able to offer their children a room of their own … tenants not only voted for it, but designed it themselves. The one complaint that was raised most often in our steering-group meetings was that ‘the council has never listened to us.’

Opponents of stock transfers argue that they were simply a second attempt to purge the country of direct state responsibility for an essential human need after the first attempt, Right to Buy, slowed down; that they were, in effect, another privatisation, and one that cost the state dear. A report on stock transfers by the National Audit Office in 2003 judged the programme a success but conceded that if councils had been allowed to use grants and loans to renovate a million homes themselves, it would have cost £1.3 billion less than getting housing associations to do it. The NAO said there were other benefits: shifting risk from taxpayers to the housing assocations, getting repairs done faster and giving tenants a bigger say (as a rule housing associations give tenants a third of the seats on the boards running their estates). Yet as the social-policy thinker Norman Ginsburg put it in his article ‘The Privatisation of Council Housing’ (2005), ‘There is no question that improvements have been accelerated by the transfer, but that is only because local authorities were prevented from doing them. There is undoubtedly increased tenant participation … but whether tenants exert any more collective influence than they did within local electoral politics is highly debatable.’ As for the notion of risk transfer, he said, was it such a wonderful thing to transfer risk from taxpayer to the assumed-to-be-too-poor-to-pay-taxes tenants? ‘It appears to be celebrating the loss of a public responsibility for meeting basic needs.’

Whether councils, given the chance, could have carried out the vast renovation programme that the housing associations are successfully pursuing (few who have lived in British cities for a generation, even if they don’t live on a council estate, can fail to have noticed how much less grotty the estates look) is a question that can’t be answered. The successful renovation of seventy thousand council houses carried out in Birmingham after its council tenants voted against stock transfer in 2002 suggests that they could. But housing associations are dominant now in the place council housing used to be, and as the effects of Right to Buy, increasing population and the failure of the market to build enough houses to cope with it have become apparent, successive governments have turned to housing associations to fill the gap. In 2005, the housing association wave came to the Cranbrook Estate.

Rather than try to transfer its stock in one go, Tower Hamlets has done it estate by estate. Its preferred bidder for Cranbrook was Swan Housing Association, created in the 1990s to own and run a set of former new-town homes in Basildon, Essex. Headed by an experienced housing manager, John Synnuck, the organisation began to expand, building homes and acquiring them from councils in stock transfers. They were opposed by an organisation called Defend Council Housing, rallied locally by George Galloway, who after his expulsion from the Labour Party over his anti-Iraq war activities had fought and won the parliamentary seat of Bethnal Green and Bow under the Respect banner. Defend Council Housing claimed that the Swan takeover amounted to a privatisation of the estate by a rapacious corporation. They won the argument and got the votes. Cranbrook is still in council hands. But supporters of the housing association claim residents made a terrible mistake; that the housing association takeover wouldn’t have been, and couldn’t have been, a privatisation at all; that the residents were deceived into opting for a bleaker, more insecure future. ‘Defend Council Housing caused real damage,’ David Orr, head of the National Housing Federation, the umbrella body for housing associations, told me. ‘They persuaded people to vote against their own best interests in pursuit of an ideology about council housing. And I think that’s unforgivable … a hundred years ago, 90 per cent of us lived in private rented housing, and most of it was squalid, and it was council housing that changed that. But the idea that the way you defend council housing and its place, not just in history but in the present and in the future, is by attacking housing associations, and by persuading people not to vote for things that were clearly in their interests – I just think that’s crass.’

In the course of the Cranbrook campaign – one of many contested by Defend Council Housing activists around the country – Galloway wasn’t always scrupulous about the facts. Like virtually all housing associations, Swan doesn’t pay dividends and doesn’t have shareholders. It was therefore inaccurate for Galloway to say of Swan: ‘These organisations exist for their own corporate reasons and their own corporate benefits, including their shareholders, to whom they distribute a dividend.’ Glyn Robbins, a housing theorist and part-time political activist who chaired the meeting where I met Pat Quinn, also took part in the anti-Swan campaign at Cranbrook. He doesn’t go as far as Galloway, but still calls housing associations ‘private companies, run as businesses’.

We met for the second time in his office at Quaker Court, the Islington council estate where he works as a housing manager. Speaking with his activist’s hat on, he told me that the promotion of housing associations as benign, philanthropic organisations was a trick. ‘They had this kind of cosy, non-threatening image. At times some were benign and did good deeds but as they became more and more reliant on private sector finance and more and more commercially oriented they have become, for people in most housing need, far more similar to the private sector. Where do we draw the line between not paying dividends to private investors and paying housing association chief executives quarter of a million pound salaries? If you want to work in the public sector, aren’t you beholden to accept a different kind of reward that reflects that ethos?’

I went to see Swan at work renovating a council estate it has taken over in Bow, another part of Tower Hamlets. Three enormous, decayed tower blocks are being refurbished inside and out in a site hemmed in by railway lines. Swan’s architects have used the space at the foot of the high-rises to build hundreds of low-rise new flats and houses that compare favourably in size and appearance to others being built by private developers elsewhere in East London. Any council tenant on the estate who wants one of the new or refurbished flats, at a rent similar to the one they were already paying, will get one. The homes left over will be let at market rents, sold as shared-ownership properties, or sold outright; Swan will use the proceeds from these commercial activities to cross-subsidise its social housing. The reason Doreen Kendall was against the Swan takeover of the Cranbrook Estate wasn’t some erroneous idea that Swan was a for-profit company, but that Swan intended to finance the refurbishment of the estate by obliterating Lubetkin’s design: their plan was to build new homes on top of and in the gaps between existing ones, gaps which, for instance, contain the Cranbrook residents’ community centre. Some of these homes would then be sold, or let out at market rents.

Even as governments have courted and flattered the housing assocations, they’ve chivvied them into becoming financially more creative in finding ways to go about their business. They’ve cut the grant they give them to help them build, forcing them to use whatever extra space they can carve out of each council estate they take over, or out of each new development they start, to build houses for sale or private rent for the purposes of cross-subsidy. By encouraging the housing associations to take on more private debt and to carry out more and more private work to fund their altruistic activities, the government makes them look more and more like for-profit companies. The danger is that social housing might ultimately become a philanthropic stub on a private body, like the donations a bank makes to charity.

There have been some troubling instances of fat cattery at the housing associations. None of the hundred names on the most recent list of housing association chief executives’ salaries published by the journal Inside Housing, which keeps them under fantastically detailed scrutiny, earns less than £100,000 a year; 16 of them (including Synnuck of Swan) earn more than £200,000. In 2010, the association Housing 21 gave its retiring chief executive, Melinda Phillips, a package worth more than half a million pounds – salary and pension worth £207,000, and what was effectively a farewell gift of £300,000. In August this year, Great Places Housing Group showed similar generosity to its retiring chief, Stephen Porter. Along with £204,000 in wages, pension payments and bonus, the board handed him a parting gift of £245,000. Altogether it was the equivalent of £28 from every Great Places tenant household.

Housing associations have diversified furiously. The Gentoo Group, created out of the transfer of Sunderland’s council houses in 2001, has gone into construction, facilities management, solar panels, bulletproof glass, train windows and a software package called Streetwise that helps housing managers track and control estate troublemakers (‘Streetwise can calculate the cost of each type of intervention or legal action taken, allowing an organisation to identify the most cost-effective way of dealing with anti-social behaviour’). A third of Gentoo’s £175 million turnover is unrelated to social housing, although the company assured me that it doesn’t subsidise its other activities from tenants’ rent. At the same time, Gentoo, whose chief executive, Peter Walls, almost doubled his salary at transfer when he switched from being the council’s director of housing, struggles to find ways to build new homes for the less well-off. Sunderland’s population is falling, and it was always part of the plan to demolish 5000 homes by 2021. But the result of knocking down 4000 former council houses, selling 4500 to Right to Buyers and building 1500 affordable rent replacements is a net loss of 7000 affordable homes.

In 2013, an over ambitious housing association, Cosmopolitan, would have gone bust had it not been taken over by another large assocation, Sanctuary. It turned out that Cosmopolitan had used its social housing assets – most of which were the seven thousand former council houses of the borough of Chester – as collateral to guarantee loans it took out to fund a student housing business. Accounting blunders meant Cosmopolitan breached its loan covenants. If Sanctuary hadn’t come to the rescue, Cosmopolitan’s tenants might now have large financial institutions as their landlords.

In recent years Swan has set up spin-off companies: Swan New Homes to build houses for sale, a private residential care company called Vivo and a property management firm, Hera. If Vivo and Hera make good profits, fine – that will go into the social housing pot. If they lose money, however, there’s a danger that Swan’s surplus will be diverted to shore up these for-profit arms. For now, three-quarters of the new homes Swan builds count as social housing. But it seems that every time the housing associations show they can deliver with reduced government support, the reduced support becomes the new norm, ready to be cut again. If there were any doubt about the way all this is heading, a rule change made in 2008 under Labour made it possible to set up for-profit housing associations – as if the party’s policy people had listened to George Galloway’s fantasy of what housing associations were and thought it was a good idea.

‘Housing associations, particularly some of the bigger ones, have now reached the stage where they have assets and knowledge and expertise that allow them to operate in a rather different market and start looking at building for sale – not just riding on the coat tails of developers but being the lead developers themselves,’ Orr told me. ‘But here’s the rub: when we move away from the model of up-front capital investment to provide social rental homes, and do things that are more commercial, that’s the point where people on the left say see, we told you, they’re all just greedy bastards who want to build and they only care about development. Which is not true, but it’s a narrative that follows.’

Government leverage over the housing associations derives above all from the fact that Whitehall sets the rents housing associations may charge, most of which are actually paid via housing benefit. There are now three different kinds of rent in Britain: market rents; ‘social rents’, which is what council tenants pay, in London typically about half market rent or less; and ‘affordable rents’, currently pegged at 80 per cent of market rents. When in 2010 the coalition cut by two-thirds the grant it gave to housing associations, it still wanted them to build the same number of houses. The only way the housing associations could do that was by borrowing more money on the market. The only way they could finance that debt was by charging higher rents. Fine, said the government, from now on, whenever you build new social housing, you’ll have to make them affordable tenancies, with those 80-per-cent-of-market rents. The indirect consequence was that the housing benefit bill went up.

‘The part of the government that’s interested in building new homes has an absolute requirement to see rents going up,’ said Orr. ‘The part of the government that’s interested in housing benefit has an absolute requirement to see rents coming down. And the bit of government that’s meant to manage all the finances, the Treasury, want to see both of those mutually contradictory things happen at the same time.’ He might have added another contradiction – that the government agency encouraging housing assocations to come up with ever more financially inventive ways of squeezing more homes out of their limited budgets is called the Homes and Communities Agency. The regulator supposed to make sure housing associations don’t take on excessive financial risk is … the Homes and Communities Agency. The policy gets more knotted still on the former council estates taken over by housing associations, where the coalition is demanding that when a social tenancy ends – when a former council tenant dies, for instance – the property is relet on an ‘affordable’ tenancy. But with the coalition’s own changes to housing benefit, poorer tenants in ‘affordable’ tenancies are finding it harder not to fall into arrears, meaning the revenue stream to the lenders the housing associations borrowed from is jeopardised – making it impossible to get further loans.

The direction of social housing policy since 1979 has been gradually to remove the state from the business of building houses, and now gradually to remove the state from the business of subsidising rent. You can imagine free marketeers believing the market can house the poor in decent comfort without the better-off being forced to chip in, although there is no evidence that it can. This is the benign view of the Thatcherites’ motive. But it is easier to believe that the actual intention – not formally designed in some conspiratorial way, and never openly described as such – is to demonetise that part of general taxation on the well-off that goes towards evening things out for the poor and replacing it with a tax in kind, a tax on conscience. To permit the gradual re-emergence of slums, in other words, in order to keep income and corporation tax low, and to make the threat to the well-off an easily ignored threat to their conscience, rather than to their wealth. To settle for history as wheel rather than ascent, in which it will eventually be time for Dickens to come around again.

There is a substantive obstacle in the way of that descent back into squalor: there is no neat way to separate the shortage of social housing from the shortage of housing in general. The government is pulling back in the face of a market that is failing across the board. Matt Griffith, author of an incisive paper for the think tank IPPR about the housing crisis, We Must Fix It, points out that the interconnecting problems afflicting the private housebuilding industry do not reflect a deeper economic malaise; they are the deeper economic malaise. Britain’s established housebuilders, Griffith reckons, no longer have housebuilding as their primary function: they’ve essentially become dealers in land. Griffith estimates that British housebuilders have enough land to build 1.5 million houses. This is much higher than most estimates because he includes not only land that has been given planning permission for homes to be built on it but also the shadow land bank: the vast stretches of agricultural land that housebuilders’ canny local agents guess will get planning permission in future, and have tied up through confidential option deals with landowners.

Why is this land not being built on faster? Because the price the builders paid for the land is tied to the price they expect to get for the houses when they do finally build on it. In boom times, they build more homes, but tend to be over optimistic about the prices they will fetch, and overpay for land accordingly. In lean times they can’t build, because to do so would be to acknowledge that they overpaid for the land, which would threaten them and the banks that lent to them with massive losses through the devaluation of their assets. Instead of competing to build the most attractive houses, the firms in the private housebuilding oligopoly compete over who can best use their land-banking skills to anticipate the next housing bubble and survive the last one. The whole system incentivises land hoarding and an undersupply of new homes compared to demand, to keep prices high. This, in turn, incentivises banks to favour property loans over other forms of lending. An incredible 76 per cent of all bank loans in Britain go to property, and 64 per cent of that to residential mortgages. That is money that could be spent on lending to other, more productive businesses. Yet it is so large a share of banks’ assets that the kind of radical reform of the planning and land ownership system Griffith wants to see might, by lowering house and land prices, bring the banks to their knees again. As Martin Wolf wrote in a despairing attack on Help to Buy in the Financial Times, ‘a deregulated and dynamic housing supply could spell financial and political Armageddon.’

Against this is David Orr’s prescription: to increase housing supply at the other end of the market with a relatively small increase in government funding to housing associations, and to hand council housing over to a new set of European-style municipal housing agencies which could borrow money without adding to the national debt. Housing associations and councils have banked land of their own and every reason to build on it. ‘What is the thing that most characterises subsidised housing? Answer: subsidy,’ Orr says. ‘If we had a government that wanted to see a significant increase in the supply of new homes they would stop asking “Can we do it?” and they would start asking “How can we do it?” Right now we spend £10.5 billion per annum on housing and transport – £9.5 billion on transport, and £1 billion on housing. If we decided to spend £8.5 billion on transport and £2 billion on housing it would still be £10.5 billion, and with that extra billion, we would be building forty thousand new homes a year before they even got High Speed 2 anywhere near a planning application.’

Making space for everyone in the crowded southern end of an island with a growing population is likely to involve everyone giving something up. No one knows the fate of the Cranbrook Estate; like Doreen Kendall, I would like to see it remain council property, yet somehow restored and properly maintained the way Skinner, Bailey and Lubetkin designed it. That’s what I think should happen. But I’m not sure how. And suppose Tower Hamlets decides, like Swan, that it wants to increase the number of homes on the site by building over its green spaces or knocking it down and starting from scratch? The council, working with Swan, has already begun doing exactly that on another estate, the brutalist concrete Robin Hood Gardens near the Blackwall Tunnel, claiming, against the aesthetic objections of Richard Rogers and Zaha Hadid, that it has the support of the majority of residents. If we campaigned against a similar project for Cranbrook, would we be righteous campaigners fighting to save the nation’s artistic heritage, or Nimbys obstructing urgently needed new homes?

The broader battle is to fight for the ideal embodied by Cranbrook: the ideal of social housing supported from general taxation on the better-off, the ideal that it is not only the prosperous who matter. Glyn Robbins grew up in a council house. Now he’s a private homeowner. His father was born in 1929 in a slum in Limehouse, since demolished. There was no hot running water there and no bathroom. Three families shared a single house. Robbins’s father’s family of four slept in a single room. In 1936, they were offered a council house in Dagenham, a suburban house with front and back gardens. The result was a bequest of stability to their children and grandchildren. ‘If I’d said to my Nan and Grandad that they might even think about buying their house it wouldn’t have made sense. They had no reason to,’ Robbins said. ‘It was only after 1979 that that temptation was dangled. With some pride they were adamant they wouldn’t buy it and never did and so when Nan and Grandad died the house got given back to the council and it should have been left to the next family on the list. But I went back recently, and of course it’s been sold, and it’s in a shit condition.’

You could see Robbins’s lament as nostalgia. After all, the slum-to-council-house journey was a one-off, exclusively for two past generations. There are no slums in Britain now, no favelas. But that would be to assume the journey couldn’t go in the other direction. One kind of move back to the early 20th century has already begun. Throughout the 1980s and 1990s we thought the proportion of homeowners would keep going up as the number of council houses went down. But since 2004 home ownership has been in decline in Britain. Since 1992, the number of people living as private renters has doubled. Julia Unwin, chief executive of the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, is pessimistic: ‘At the turn of the 20th century, the free market had provided squalid slums. We undoubtedly face the re-creation of slums, the enrichment of bad landlords, the risk of people being destitute. Beveridge had soup kitchens. We have food banks. We’ve got something that does take us back full circle, a deep divide in way of life between people who are reasonably well off and those who are poor. There’s always been a difference, but the distinction seems to be more stark now.’ The advent of the age of gentrification doesn’t preclude the advent of slumification, and nostalgia becomes prophecy.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.