The American artist Christopher Wool’s large abstract paintings are often beautiful, but they are so emptied of content that it is at first hard to know what to make of them. For the first ten years or so after he came to attention in the mid-1980s, he was considered an artist’s artist: he didn’t have a large public following or much of an international reputation. All this has changed. Now his work is exhibited and written about everywhere, and is highly successful in the art market. Many now see Wool as the heir to Andy Warhol, the next great link in an American tradition of painting that began in the postwar years of abstract expressionism and pop art. A retrospective can be seen at the Guggenheim in New York (until 22 January).

The key to Wool is his use of printing techniques to make ‘original’ paintings, and the way in which he proposes reproduction itself as the subject matter for abstract painting. His breakthrough works of the mid-1980s were made with a rubber roller incised with a pattern that could then be transferred to create an all-over pattern on a surface – often aluminium or rice paper. His winning gambit was to use black enamel and acrylic paints, unusual media that have the feel more of viscous printing ink than of paint. Some of the surfaces seem like decorative wrought iron, others might have been taken from a wallpaper pattern book. A further series uses cheap and cheerful ‘mid-century modern’ designs.

Abstract painting has always had an uneasy relationship with decorative art. How to partake of its effects, while achieving a sense of reflection and the force of statement? The mistakes and infelicities that Wool allows to drift in to his ‘decorator’ works (my term) are one solution. The jerky registration of the roller paintings and his later screen prints suggests a loose matrix in which the patterns and forms jiggle nervously about. Everything is not quite right, they seem to suggest, things are coming apart, something nice is turning nasty.

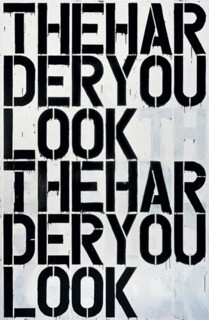

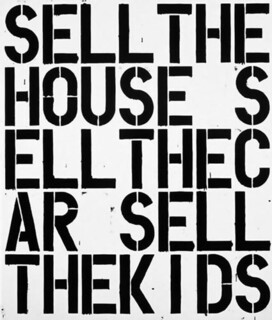

These sentiments are given a more direct, unambiguous treatment in Wool’s Word Paintings. Like tabloid headlines, letters are stencilled in black enamel, arranged in a straight grid running down the white surface. The lack of punctuation makes them difficult to decipher at first glance. Words and phrases have been borrowed, or seem to have been picked up somewhere, snatched from the air in Manhattan perhaps, insults traded, exclamations overheard, tired of meaning. ‘THE HARDER YOU LOOK THE HARDER YOU LOOK,’ one of them reads. Another, ‘HELTER HELTER’, might have been made for the Guggenheim. Blue Fool (1990) shouts the word ‘fool’ in blue: the viewer feels indicted; this is a showdown with contemporary art scepticism. Perhaps the best known of the series delivers the phrase ‘SELL THE HOUSE SELL THE CAR SELL THE KIDS,’ taken from the film Apocalypse Now. (The large version of this painting was sold at auction in New York during my visit, after fierce bidding, for $26.5 million.) There is something very brute and American here, a feeling that spills over into the abstract paintings alongside: ‘TRBL’, ‘AMOK’, ‘RIOT’.

In appearance, if not in mood, the Word Paintings recall the alphabet and number paintings of Jasper Johns. They echo the way Johns builds up a surface, messily erasing previous versions, turning letters and numbers into visual symbols. Wool is ruder (‘GET THE FUCK OUT’), and less pictorial; he stays on the side of Warhol in draining his images of meaning, where Johns builds up a ‘meaningful’ sense through layering and the reiteration of elements. In a series of paintings using the innocuous motif of a flower, he layers the images so thickly that the enamel clogs into a black mess, as if to say that the flower is just an expendable trope, a means to an end.

Evacuating paintings of the personal touch by way of printing techniques is one way of suggesting the anonymity of modern urban life, of getting that gritty feeling into the paintings. Around 1995, however, a new element appeared in Wool’s work that seemed to reel back on the doctrine of impersonality: spray-gun painted loops whirled onto the painting surface. They could be seen as anarchic, threatening even, but it seems more truthful to read them as the artist obsessively, and rather wistfully, signing his name with swirling loops: wool, wool, wool. The effect is soft and rather beautiful. Around the diffused lines of black enamel there is a penumbra of faint tone and along the lines, drips, where Wool has slowed the spray gun down enough for the paint to well thickly. Over time the loops became slower, more like meandering lines; once he stopped making the Word Paintings in 2000, the loops became the element of écriture in his otherwise abstract painterly fields.

‘I get the paint right on the surface,’ Willem de Kooning once said. Wool gets the surface right on the painting, giving a sense of flatness that implies printed marks and painted marks sandwiched together with the tiniest of gaps between the two. In the late 1990s he further emphasised this peculiarly anonymous quality of the surface when he began using silkscreen images, taken from photographs of his own work. He went the full Warhol, as it were. Painted loops were photographed, turned into silkscreen, and then printed directly back on canvas, a reiteration summed up in the title of a work from 2001, He Said She Said.

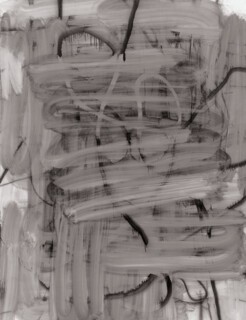

In the Guggenheim show, these large silkscreened works are hung next to Wool’s Grey paintings, made by wiping a turpentine-soaked rag over a painted surface. He liked the effect, and made it his own, combining the wiped marks with sprayed loops to create complex abstract fields that began to look, squinted at from a distance, like black and white reproductions of paintings by Franz Kline or de Kooning. The point of showing the silkscreen works next to the paintings seems to be to suggest some kind of equivalence, the result of a ‘collapse of boundaries’. True, some of the silkscreen works are finished by hand so that they really are ‘paintings’. But the paintings are more interesting and better than the printed works – as paintings tend to be. Untitled (2007) has a monumental scale of gesture and sense of vigour that can hardly be found in the silkscreens. Soft enamel washes create a unique effect like misty celluloid or the ghostly forms of X-ray photography: smooth, faded, translucent. It has a kind of weightlessness, perhaps the mark of all truly abstract painting, defined not by the absence of recognisable things but of natural forces, principally the one that keeps us grounded and defines our shape.

A Grey painting from 2008 is finished with a spool of black spray-gunned lines, given a gothic spikiness by a filigree of drips down their length, masterfully controlled. At first I preferred this one to the 2007 Grey painting from the Tate which hangs alongside and seems quieter, more deferential, the result of a moment of scrubbing out rather than building up. Yet backing up around the Guggenheim spiral, the Tate work begins to hold itself in a fuller, more interesting way, unravelling its message in its own time. Is Wool’s work any good? Is this some joyless endgame of painting, or are these elegant, intellectually challenging images? Either way they seem to capture the hard, unsentimental energy of New York, with its ecstatic highs and suicidal lows. And that isn’t bad going.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.