‘All actors want to play Disraeli, except fat ones,’ the American filmmaker Nunnally Johnson said. ‘It’s such a showy part – half Satan, half Don Juan, man of so many talents, he could write novels, flatter a queen, dig the Suez Canal. Present her with India. You can’t beat that, it’s better than Wyatt Earp.’ And it’s as good as Lord Byron. Take the life of Disraeli, for ‘novelist’ read ‘poet’, and you’ve got an epic about what happened to Byron after he’d recovered from that deadly fever at Missolonghi.

Having fought for Greek independence, he falls out of love with the country and returns home to make a career in British politics. He comes with no fortune, no influence and an unsavoury reputation. The territorial and financial magnates of the Whig party don’t want to know. Undaunted, Byron reinvents himself as a Tory: the Tories are now led by his contemporary and old school friend, Robert Peel. At Harrow, Peel was a model pupil; Byron was a madcap, and he still thinks a lot more of Peel than Peel thinks of him. Peel is committed to transforming the Tory Party. He’s out of sympathy with horsey aristocrats, rustic squires, dissolute half-pay officers, high and dry parsons and Romantic intellectuals. He wants to promote men like his father and grandfather – sober, hard-working, hard-headed industrialists with the Bible in one hand and The Wealth of Nations in the other. Byron doesn’t fit, so Peel leaves him out of his cabinet in 1841.

Hurt and resentful, Byron turns back to literature. He invents a new sort of Tory-radical fiction – satirical, engaged with recent history and current affairs, and bitingly critical of Peel. This brings him to the attention of a group of young and wealthy backbench Tories who want a high-profile leader for their campaign against Peel’s ‘Conservatives’, and Peel is duly destroyed. Deserted by the majority of Tory MPs, he’s forced to resign and dies a few years later as the result of a riding accident. Byron eventually finds himself chief of the truncated, old-fashioned Tory Party, with no apparent prospects of substantial power. Very late in life, he unexpectedly becomes prime minister with a big parliamentary majority and the support of a devoted queen. By now he is no longer Byronic. The athletic figure is bent; the hyacinthine locks have vanished and their ghostly remnant is dyed; the Apollonian cheeks are withered and rouged. The crusader for compassionate Toryism falls asleep during cabinet discussions of welfare legislation. The once restless traveller hardly ever goes abroad. The champion of oppressed nationalities has become an apologist for the Turkish sultanate, Britain’s broker for imperial trophies (Cyprus, a trunkful of Suez Canal shares) and the transformer of English queens into empresses of India. Peel, reincarnated as William Gladstone, denounces him from beyond the grave. Gladstone sweeps to victory, Byron is toppled and Peel is avenged. Byron dies, leaving posterity perplexed. Had he been a writer who happened to become prime minister, or a prime minister who happened to be a writer? Professors of history talk a great deal about him, but professors of English ignore him and publishers put his works out of print.

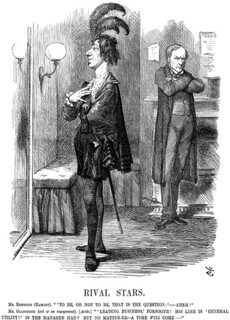

Disraeli saw himself as Byron resurrected, and Gladstone saw him as Byron travestied. In a Punch cartoon of 1868 Disraeli is looking into a full-length mirror with a fatuous smirk: he sees Byron. Gladstone is standing by, arms folded, looking grimly on. He sees what we see – a conceited thespian. Can either see what’s there? Or does each see half of the truth?

Disraeli was 16 years younger than Byron and Peel, hadn’t been to Harrow, and in 1841 was a junior (though conspicuous) backbencher remote from Peel’s inner circle of associates and friends. There was no good reason for Peel to treat him as he would, or should, have treated Byron – or for Disraeli to resent it when he didn’t. But Disraeli had so identified himself with Byron that he reckoned Byron’s entitlements were his own. During his 17-month foreign excursion of 1830-31, he’d ignored the Grand Tour route and retraced Byron’s steps through Spain, Greece, Malta, Albania and Turkey instead. He would use his travels in autobiographical fiction: unmistakably Byronic heroes – rich, beautiful, aristocratic, young – are driven by Sehnsucht and restlessness to pursue self-apotheosis and the meaning of life in exotic lands. Macaulay thought that Byronism was finished by 1830, but in Disraeli it ran much deeper and lasted much longer. His father, a literary antiquarian, had been admired by Byron, and would die in the arms of Byron’s old servant, the gondolier Tita Falcieri, whom Disraeli brought back from Venice. On the publication of his first novel, Vivian Grey, in 1826, Disraeli at 22 found literary fame overnight, as Byron had at 24. In his fourth novel, Alroy (1833), he’d recycled, in verse-prose, a Byronic theme – the struggle of an oppressed nation to be free. Like the 19th-century Greeks, the 12th-century Jews triumph over Turkish tyranny; and Byron’s diatribe against imperialism is vindicated by the terrible retribution that overtakes the Jewish hero Alroy when he forsakes the cause of Palestine for overlordship of Asia. In his sixth novel, Venetia (1837), he fictionalised Byron as Lord Cardurcis, a poet celebrating not the Greek but the American war of independence; and two years later he published Count Alarcos, a five-act verse play in imitation of Byron.

Disraeli shared Byron’s bisexuality, and also suffered psychologically for a physical handicap. Byron was lame; beggars used to mock him. Disraeli wasn’t lame, but he looked Jewish: ‘I never saw any other Englishman look in the least like him,’ Nathaniel Hawthorne said. Because of his features, he was ragged at school, pelted with pork offal during elections by mobs, and transmogrified by cartoonists. He’d been baptised as a teenager and went to church regularly, but he was never allowed to forget that in 19th-century Britain, once a Hebrew meant always a Jew. Like Byron, he coped with his stigma by trying both to conceal and to exploit his handicap. Byron had dissimulated his lameness with vigorous athleticism and a riotous lifestyle, while playing up its erotic appeal. Disraeli disguised his origins with ostentatious Englishness – a dandy when young, later funereally staid. He invented a Sephardic ancestry for himself – as aristocratic as anyone’s – and insisted that the English, by virtue of their religion, literature and laws, were as Jewish as he was.

Douglas Hurd and Edward Young’s Disraeli: or, the Two Lives, and Robert O’Kell’s Disraeli: The Romance of Politics diverge when they come to Disraeli’s Byronism. Hurd and Young wave it aside: ‘Disraeli aspired to a career like that of Byron, Shelley and the other Romantics, yet disqualified himself by preferring splendour to beauty.’ Disraeli, they argue, had two lives: one lived in actuality, the other reserved for his imagination. Disraeli’s ideas, they explain,

were like a collection of silver, proudly displayed, constantly polished, often added to, but only occasionally used in the course of daily life. His ideas were eccentric in the literal sense; they were distinct from the day to day activities of his political career. Every now and then, Disraeli opened this storehouse, took out a handful of ideas and tested them as creatures of fiction or as deft phrases for a speech. After carefully perfecting and polishing them, Disraeli put the ideas back in the cupboard for another day.

This authorises a blanket dismissal of the fiction: ‘When it came to a conclusion, or a call for a new kind of politics, the plots collapsed and the sentences descended into banality … His novels are [not] all-important. Far from it: they are not great works.’ Hurd and Young’s Disraeli is a schemer rather than a thinker, fired up much more by ambition than by imagination.

O’Kell’s interpretation is fundamentally different. Disraeli had two careers, but only one life. Treating ‘the fiction as a form of autobiography and the politics as a form of theatre’, O’Kell portrays an intensely ambitious, narcissistic and self-exalting but also fragile young man confronting the quintessentially Byronic dilemma: How to gain the world without losing his soul? For, like Byron, Disraeli is both seduced by the world and repelled by it. In Byron’s poetry, the ‘deformed’ is ‘transformed’, and so in Disraeli’s fiction the ‘dirty’ Jew is purified by a hard-won victory against the baser self. Disraeli’s desire for worldly success was driven, like Byron’s, by the stigma he carried; his aversion to the world was intensified, again like Byron’s, by a Romantic ideal of his integrity. Disraeli’s fiction, O’Kell claims, is inspired by an inner conflict between the will to succeed and a longing for innocence.

Yet Hurd and Young have a point: Disraeli was too idiosyncratic to be always and everywhere a clone. O’Kell pushes his argument too far by reading Byronic ‘psychological romance’ into virtually everything Disraeli wrote. Coningsby, Sybil and Tancred are the best known of his novels, but aren’t the most accessible, since they interleave history with flights of fancy. Disraeli almost certainly never believed that his vision of ‘Young England’ – a neo-feudal utopia led by a rejuvenated aristocracy and re-spiritualised Anglican Church – could ever become reality. So understanding this fiction as ‘a form of compensation for failure or defeat, in imagining transcendent success’, and ‘a means of self-discovery’, makes sense. It works less well for Endymion (1880), Disraeli’s last novel, because by that point autobiography had mellowed into reminiscence and the angst of ambition and failure were softened by a valedictory glow. With O’Kell, this sort of cross-referencing becomes an end in itself and sometimes falsifies both the politics and the fiction. Disraeli himself never took all his novels seriously (he later tried to suppress Vivian Grey and The Young Duke); yet O’Kell seems unable – or unwilling – to recognise a potboiler when he sees one.

It isn’t the case that Disraeli always used fiction to sort out problems in his life – between 1847 and 1870, he didn’t write any fiction. Until his marriage to a wealthy widow in 1839, his finances were catastrophic and he had to write novels to avoid imprisonment for debt. Vivian Grey, The Young Duke (1830) and Henrietta Temple (1837) are money-spinners trading on the sure-fire commercial appeal of spot-the-celebrity social satire, silver-fork divertissement and boudoir romance. From the 1850s his worries about the contamination of politics by fiction all but ended his career as a novelist. ‘I wish, like you, I could console myself with reading novels or even writing them’, he wrote to Lady Londonderry in September 1857, ‘but I have lost all zest for fiction and have for many years.’ British India was in rebellion, and Britain was shocked and outraged. Disraeli was dismayed by the atrocities, but detected wild exaggeration and was one of the few public figures who argued against indiscriminate British retaliation. ‘I cannot altogether repress a suspicion,’ he told Lady Londonderry,

tho’ it is only for your own ears, that many of the details of horrors … are manufactured. The striking story of Skene at Jhansi, his deeds of heroic romance, worthy of a paladin, then kissing his wife and shooting her etc., etc. – all appear, now, to be complete invention …

The detail of all these stories is suspicious. Details are a feature of the Myth. The accounts are too graphic, I hate the word. Who can have seen these things? Who heard them? The rows of ladies standing with their babes in their arms to be massacred, with the elder children clutching to their robes – who that would tell these things could have escaped? One lady says to a miscreant, ‘I do not ask you to spare my life, but give some water to my child!’ The child is instantly tossed in the air and caught upon a bayonet! Those who invented the Skene story might invent others.

This experience explains why twenty years later, as prime minister, he was sceptical about stories of Turkish atrocities against Christian insurgents in Bulgaria. He thought he recognised the same Evangelical propagandists and the same Evangelical hysteria and dismissed the reports as ‘coffee-house babble’. He stuck to Britain’s traditional policy (later inherited by Nato) of propping up Turkey to hold back Russia – thereby bringing out all the anti-Semitism of his enemies. William Morris called him ‘the Jew wretch’ who was ‘against freedom, against nature, against the hope of the world’. According to the historian E.A. Freeman, he was ‘the friend of the Turk and the enemy of the Christian … sacrificing the policy of England, the welfare of Europe … to Hebrew sentiment.’ Hurd and Young modify their argument at this point. Disraeli, they claim, ‘carried into foreign policy as much of the paraphernalia of the novelist as proved portable’; the Eastern Question aroused ‘his fascination as a Jew and novelist with the kaleidoscope of Eastern faiths and mysteries’. But why the modification? In the view of Prime Minister Disraeli, imagination was toxic when combined with foreign policy. Gladstone was dangerous because he was the hostage of mythomaniacs, trumpeting against ‘Bulgarian horrors’ and turning electioneering into ‘a pilgrimage of passion’. He was ‘a sophistical rhetorician inebriated by the exuberance of his own verbosity’. This legendary combat is at the heart of Dick Leonard’s The Great Rivalry, which uses the old compare and contrast formula, hopping between the two protagonists, but updating the story with the recent work of Colin Matthew, Roy Jenkins, Richard Shannon, John Vincent, Sarah Bradford and Stanley Weintraub. Essentially it’s dry-bones parliamentary history – elections, cabinets, reshuffles, bills, budgets, divisions, dissolutions – and its verdict on the falling out hardly deepens our understanding: ‘By the end of [Disraeli’s] life something approaching cool hatred was their mutual attitude.’ Cool, Gladstone? A hater, Disraeli? According to his Victorian biographer James Anthony Froude, ‘in all his life he never hated anybody or anything.’

Between them Gladstone and Disraeli clocked up twenty years of prime-ministerial service – a third of Victoria’s long reign – and were both international celebrities. Disraeli was the focus of the world’s attention at the congress of Berlin in 1878, and posthumously made it to Hollywood not once but several times. But he was not as eminent as Byron and Gladstone wasn’t as eminent as Peel. A parliamentary battle between Peel and Byron would have been the stuff of tragedy. The battle between Gladstone and Disraeli was nearer to Gilbert and Sullivan than it was to Sophocles. Nor were they equally eminent and equally Victorian. Gladstone has generally been regarded as a prime minister who got things done: he overhauled the civil service, the army and parliament, substituting meritocracy for patronage and democracy for oligarchy. He introduced universal elementary education, opened up Oxbridge to non-Anglicans and forced the English political establishment to confront the problem of Ireland. His budgets (he was twice chancellor of the exchequer, and twice both chancellor and prime minister) opened the way to a global free-market economy. The fact that he was a poor tactician (his campaign for Irish Home Rule failed, split the Liberal Party and sent it into all but terminal decline) has made him seem greater: a magnificent failure who put justice above the interests of party.

Disraeli didn’t get things done – he let things happen. The Second Reform Act, passed in 1867 when he was chancellor and leader of the Commons, came about more by accident than by design. The public health legislation of his second ministry (1874-80) was already in the pipeline and he did little more than wave it through. But his tactics were impeccable. Having split the Tory Party once, he was determined never to do so again, and played the game so cleverly that the party, fault lines and dogfights notwithstanding, has held together ever since. He probably saved the monarchy, then at an unprecedented level of unpopularity. Doted on by the widowed Victoria, he was able to coax her out of semi-retirement and transform a musty institution into a form of theatre no theatre could rival. Less eminent than Gladstone, then, but arguably more successful.

He was unequivocally less Victorian. Since the publication of his private diaries, Gladstone has seemed more Victorian than ever. Macaulay once called him ‘the rising hope of those stern unbending Tories’. He ceased to be a Tory – after Peel’s death he led the Peelites into an alliance with the Whigs and thus inaugurated the Liberal party – but he remained stern and unbending. Gladstone appears in O’Kell and Leonard’s books bedevilled by testosterone: trying to dampen his libido by chopping down trees, flagellating himself and writing a treatise on Hell, while his own oratory and his work among prostitutes inflamed it. He was especially overheated by the reports of rape in Bulgaria, and ranted against ‘the unbridled and bestial lusts’ and ‘the fell satanic orgies’ of the Turks. He terrified the queen – and it’s no wonder, if he glared at her as he glares at us from faded photographs. Disraeli never glared. When Gladstone was in full spate in the House of Commons, he’d merely insert his eyeglass and look wearily up at the clock. Happily and childlessly married, Disraeli was unproblematically unfaithful (there’s some evidence of two illegitimate children). He was agnostic without being agonised, and his fiction isn’t edifying. ‘I cannot understand that he should have instigated anyone to good,’ Trollope said. So, although Trollope adopted Disraeli’s innovations (political fiction, a saga featuring the same characters in successive novels), neither he nor the other high Victorian literati ever accepted him as one of themselves. Nor was he. As O’Kell points out, the most ‘Victorian’ of his novels, Sybil, is also the least characteristic. It engages as conscientiously as the fiction of Dickens, Gaskell and Kingsley with the ‘condition of England question’, ranging from the workshops and factories of the Midlands and North to the London slums, but it relies heavily on official publications, and its proletarian episodes are unique in Disraeli’s oeuvre. He sympathised with the poor, but couldn’t identify with them (he seldom spoke to the servants in his London home) and their plight hindered rather than roused his imagination. There’s no Dickensian compassion or Carlylean indignation in Sybil – only melodrama and rhetoric.

‘Victorian’ is an unstable category, but Victorianism as popularly understood passed Disraeli by. His last novel, Endymion, left the Archbishop of Canterbury with ‘a painful feeling that the writer considers all political life as mere play and gambling’. He belonged to the days before the Evangelicals had sobered up the aristocracy, or royalty had forsaken vanity fair in Brighton for family prayers on the Isle of Wight: a link not only with Byron, but with Beckford, Brummel, D’Orsay, Blessington, Peacock and Samuel Rogers too. His most flamboyant official measure, the Royal Titles Act of 1876, savoured of the Regency. The conventional view, adopted by O’Kell, Hurd and Young and Leonard, is that this was controversial because it was un-British. British monarchs were kings and queens; imperial titles were reserved for Continental autocrats and mountebanks and Asiatic despots. But there was surely a further reason: the new royal style was unpopular because it was un-Victorian. Reinvented as empress of India, Queen Victoria looked ready to abandon Osborne House and move back to the Royal Pavilion. Yet Disraeli was also a bridge between the Regency dandies and the fin de siècle decadents. When he returned to fiction in 1870, he sounded a new note. The cut-glass aphorisms and comic cameos are still there, but the register has shifted from satirical to surreal. There’s a foretaste of Wilde, Beerbohm and Firbank in the aristocrats, aesthetes, amazons and ecclesiastics who ‘glide’ and gesticulate in the timeless elsewhere of Lothair.

Tradition has it that Disraeli is remarkable because he was an outsider who came with nothing from nowhere and made it to the top. Robert Blake, in his groundbreaking biography of 1968, rightly challenged this view. Disraeli’s Anglo-Jewish bourgeois background was privileged enough; and even though he was an adventurer and exotic, the odds against him weren’t that heavy. When Disraeli was young politics was open to anyone who was male, owned property of a certain value and was willing to take an Oath of Abjuration ‘on the true faith of a Christian’; and the Tory Party, unlike the Whig Party, was not socially exclusive. In the 1841-42 session there were two black Tory MPs in the Commons. Pitt, George Canning, Lords Lyndhurst and Eldon, all top-ranking Tories during Disraeli’s lifetime, were respectively the great-grandson of an East India shark, and the sons of an Irish actress, an American artist and a Newcastle coal merchant. By looking at Disraeli neither as a prime minister who wrote novels, nor as a novelist who became prime minister, but as both political and literary, O’Kell has replaced the old divided Disraeli, shining twice with secondary light, by a single Disraeli who’s a star. But perhaps Disraeli is remarkable most of all because power never coarsened him as it coarsened others (Canning, Lloyd George, Thatcher) who climbed a long way to reach it. Power refined him, liberating him from Byronic self-infatuation. As a tyro-politician, he’d satirised the absurdity of others. As an ageing prime minister, he was more than ever aware of his own absurdity. When he accepted an earldom in 1876, he chose a title he’d invented as a novelist fifty years before. ‘Lord Beaconsfield,’ a character in Vivian Grey says: ‘a very worthy gentleman, but between ourselves, a damn fool.’

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.