When an ailing John Maynard Keynes travelled to the American South in March 1946, he was delighted by what he found. The ‘balmy air and bright azalean colour’ of Savannah offered a welcome reprieve from the cold and damp of London, he wrote on arriving, and the children in the streets were livelier company than the ‘irritable’ and ‘exceedingly tired’ citizens of postwar Britain. Keynes was in Savannah for the inaugural session of the board of governors of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank, two institutions he had helped found at the Bretton Woods Conference of July 1944. He was desperate to persuade the Americans not to place the headquarters of the two institutions in Washington, where he feared they would function more as appendages of the American state than as truly international bodies, but their location in the American capital was all but a fait accompli, requiring only a handful of votes from the odd array of allies the US had assembled at the meeting. Keynes’s last effort to check the growth of American power had failed. He died six weeks later.

At the end of the Second World War, many thought that a lasting peace would be possible only if we learned to manage the world economy. The fact that the worst war in history had followed shortly on the heels of the worst economic crisis seemed to confirm that international political crisis and economic instability went hand in hand. In the 1940s, this was a relatively new way of thinking about interstate relations. Negotiations for the peace settlement after the First World War had largely skirted economic questions in favour of political and legal ones – settling territorial borders, for example, or the rights of national minorities. When Keynes criticised the peacemakers in 1919 for ignoring Europe’s economic troubles, and for thinking of money only in terms of booty for the victors, he was ahead of his time: ‘It is an extraordinary fact that the fundamental economic problems of a Europe starving and disintegrating before their eyes, was the one question in which it was impossible to arouse the interest of the Four,’ Keynes wrote in The Economic Consequences of the Peace, referring to the quartet of national leaders who shaped the Treaty of Versailles. Their indifference wasn’t much of a surprise: national leaders at the time had little direct experience in managing economic affairs beyond their own borders. The worldwide commercial system that had sprung up in the decades before the war had been facilitated largely through the efforts of private business and finance; the gold standard set the rules of exchange, but states mostly stayed out of the way, except when lowering trade barriers or enforcing contracts. When things went badly, they didn’t try to intervene.

This began to change after 1918. As Europe lurched from one economic crisis to another, it became obvious that more durable solutions needed to be found. The newly formed League of Nations took up the charge, fulfilling economic and financial functions well beyond what its founders had envisaged: rescuing Central and Eastern European states from postwar hyperinflation; collecting and interpreting statistical data; and calling a series of (largely unsuccessful) international conferences on trade and finance, most famously in London in 1933. By this point, Europe’s economies had begun to spiral out of control, as the Depression’s contagion spread quickly across the Continent and into Britain, destroying the banking systems of nearly every state it touched. Investors moved their money from country to country, leaving a trail of bank runs and currency crises. States raced to devalue their currencies in an escalating competition to achieve an advantage, and erected new barriers to trade and exchange. Global commerce collapsed, states turned inward, and empires contracted: the new German Reich and the Japanese Empire built regional economic blocs in the name of the fashionable ideal of national self-sufficiency, while Britain established a system of exclusionary and preferential trade with its colonies and dominions.

In the early years of World War Two, when Allied and Axis planners both began to imagine what the postwar world might look like, the question of how to prevent a return to the economic chaos of the 1930s was uppermost in their minds. In a series of negotiations that began in 1941 and culminated in the Bretton Woods Conference of July 1944, British and American officials debated how to re-create a stable and open capitalist world economy in a way that would moderate the excesses of capitalism and give states more leeway to pursue national economic policies. What was obvious was the need for a new form of international governance: a permanent system, regulated by laws and overseen by international bodies, to manage the interaction of national economies. Nothing like it had ever existed before. The new, interventionist model of organised capitalism – that of the American New Deal state – was to be scaled up to the entire world.

This was no easy task: it required the rules of international finance to be completely rewritten. But when British and American officials opened discussions, they turned first to the politically charged question of trade. It was an inauspicious start. In the 1930s, the US State Department had been taken over by the zealous free trade philosophy of the then secretary of state Cordell Hull, and as the US edged closer to outright support for the British war effort in 1941 – and a bankrupt and war-weary Britain grew more desperate for US aid – an opportunity seemed to arise to put Hull’s laissez-faire visions into practice. Article VII of the Lend-Lease Agreement stipulated that, in exchange for American aid, Britain would agree to forego all future discrimination against US imports. In essence, this meant the abolition of Britain’s system of imperial preference. (One Conservative peer referred to the demand as the ‘Boston Tea Party in reverse’.) Many saw imperial preference not only as the economic backbone of empire, but also as a means of mitigating what promised to be Britain’s very weak postwar position: giving up its system of trade barriers and exchange controls threatened to expose Britain to cheap foreign competitors, and leave it fatally attached to the US if the latter went into recession after the war (as many predicted). Keynes reflected a common British feeling when he remarked in March 1941 that US officials were treating Britain ‘worse than we have ever ourselves thought it proper to treat the humblest and least responsible Balkan country’.

Were the British being bullied? Many Conservatives and imperialists believed so, and it’s one of the core assertions of Benn Steil’s new history of the negotiations leading up to Bretton Woods. On Steil’s view, Britain was pressured into making a ‘Faustian bargain’: give up the one thing that seemed to guarantee its continued existence as an empire in exchange for enough money and goods to make it through the war. According to Steil, the US pursued wartime economic negotiations in such a way as to guarantee its postwar dominance. ‘At every step to Bretton Woods,’ Steil writes, ‘the Americans had reminded [the British], in as brutal a manner as necessary, that there was no room in the new order for the remnants of British imperial glory.’

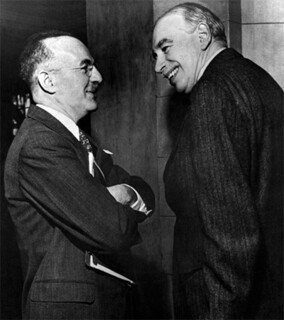

This is going a bit far, and Steil’s focus on imperial preference leads him to downplay the consensus British and American negotiators managed to achieve on the fundamental aims and priorities (if not the institutional details) of the new economic system. When the Anglo-American conversation shifted away from trade and towards the seemingly technical issues of currency and finance, progress towards a deal proceeded more smoothly. In August 1941, Keynes, now adviser to the chancellor and leading postwar economic planning, returned from negotiations over Lend-Lease in Washington to draft plans for a new international monetary regime. Over the course of several meetings from the summer of 1942, Keynes and his American counterpart, the economist and US Treasury official Harry Dexter White, traded blows over how to rewrite the monetary rules of the international economy. They made curious sparring partners: Keynes, the world-famous economist and public intellectual, pitted against White, an obscure technocrat and late-blooming academic born to working-class Jewish immigrants from Lithuania and plucked by the US Treasury from his post at a small Wisconsin university. Neither seemed to enjoy the company of the other: Keynes was disdainful of what he saw as the inferior intellect and gruff manners of the ‘aesthetically oppressive’ White, whose ‘harsh rasping voice’ proved a particular annoyance. Keynes, meanwhile, was the archetype of the haughty English lord; as White remarked to the British economist Lionel Robbins, ‘your Baron Keynes sure pees perfume.’

Squabbles aside, the two men ended up largely in agreement about the basic aims of the new international monetary system: to stabilise exchange rates; facilitate international financial co-operation; prohibit competitive currency depreciations and arbitrary alterations of currency values; and restrict the international flow of capital to prevent the short-term, speculative investments widely believed to have destabilised the interwar monetary system. They also agreed on the need to establish a new international institution to provide financial assistance to states experiencing exchange imbalances and to enforce rules about currency values (what would become the International Monetary Fund), and another to provide capital for postwar reconstruction (the future World Bank). A closely managed and regulated international financial system would replace the unco-ordinated and competitive system of the interwar years. And with currencies stabilised – so they hoped – world trade could be resumed.

The main disagreement between Keynes and White had to do with the remit of the new international institutions. Keynes’s plans, which reflected Britain’s interests and needs as a debtor, called for the establishment of an International Clearing Union – basically, a world central bank. This would issue an artificial international currency called ‘bancor’ to settle payments imbalances between states, and allocate funds from creditor countries (like the US) to debtor countries (like Britain) to facilitate this process. White’s proposed Stabilisation Fund would issue loans to countries towards a similar end, but would make fewer demands on creditor countries – and would be designed in a way that allowed the US a greater say in how it operated. In the autumn of 1943, when British negotiators agreed under American pressure to give up Keynes’s idea of a clearing union, the outlines of a final deal fell quickly into place. By April 1944, a compromise – one that reflected White’s plans more closely than Keynes’s – was on the table. The following month, Roosevelt’s government formally invited most of the non-Axis states to an international conference in the United States to hammer out details and design the new institutions.

One of the most innovative aspects of the Anglo-American deal was the fact that it prioritised the need for full employment and social insurance policies at the national level over thoroughgoing international economic integration. To this extent, it was more Keynesian than not – and it represented a dramatic departure from older assumptions about the way the world’s financial system should function. Under the gold standard, which had facilitated a period of financial and commercial globalisation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, governments had possessed few means of responding to an economic downturn beyond cutting spending and raising interest rates in the hope that prices and wages would drop so low that the economy would right itself. Populations simply had to ride out periods of deflation and mass unemployment, as the state couldn’t do much to help them: pursuing expansionary fiscal or monetary measures (what states tend to do today) would jeopardise the convertibility of the state’s currency into gold. For these reasons, the gold standard was well suited to a 19th-century world in which there were few organised workers’ parties and labour unions, but not so well suited to a messy world of mass democracy. The Keynesian revolution in economic governance gave the state a set of powerful new tools for responding to domestic economic distress – but they wouldn’t work as long as the gold standard called the shots.

What was needed, and what both Keynes and White wanted to establish, was a system of fixed but adjustable exchange rates, which would allow states to make domestic policy without worrying too much about how it would affect their international economic position. Along with capital controls, this system would work to stabilise currencies, as the gold standard had done, but in a way that gave states more breathing space to pursue the interventionist and welfarist techniques of national economic management that had recently come into vogue across the Atlantic world. The compromise that Keynes and White reached was based on this fundamental insight, and reflected what had become a new (if fleeting) consensus: that the state owed its citizens basic economic security. By telling the story of the road to Bretton Woods as one primarily of conflict and competition, Steil gives short shrift to this larger story, and misses how remarkable it was that these two imperial powers, in the middle of the Second World War, agreed to rewrite the rules of global capitalism to make the world safe for the interventionist Keynesian state.

The convocation of the United Nations Monetary and Financial Conference, where the Keynes-White deal was to be approved, was scheduled for 1 July 1944, three weeks after the Allied invasion of Normandy. Besides the obvious challenges this date posed for transatlantic travel, Washington had a reputation for its unforgiving summer weather. Keynes, already in poor health, insisted that the meeting take place somewhere cooler, preferably in the Rocky Mountains. On the advice of the State Department, the US Treasury secretary Henry Morgenthau selected the lavish Mount Washington Hotel in the small New Hampshire village of Bretton Woods. The hotel, the largest building in the state, was theoretically well suited to house the 730 delegates, representing 44 countries, that Roosevelt had invited to the conference: it boasted its own power plant and post office, an 18-hole golf course, a church, beauty parlour and barber shop, a bowling alley and two cinemas. The Mount Washington had been shuttered for two years of the war, and was in complete disarray when the guests began to arrive; an undermanned hotel staff was forced to ask for help from a group of Boy Scouts and military personnel. (Last-minute preparations had been so anxiety-inducing for the hotel manager that he locked himself in a room with a case of whiskey.)

When the delegates showed up on 1 July, a senior manager of the Mount Washington was reportedly shocked to find himself among a ‘gathering of Colombians, Poles, Liberians, Chinese, Ethiopians, Russians, Filipinos, Icelanders and other spectacular people’. Getting to the US hadn’t been easy: security precautions in the Atlantic for the D-Day invasion had slowed the journey of the British and European representatives aboard the Queen Mary, and wartime conditions had kept many states from sending their official economic ministers. (The representative of Guatemala, Manuel Noriega Morales, was a graduate student in economics at Harvard.) On 30 June, special sleeper trains (referred to as ‘the Tower of Babel on wheels’) departed from Atlantic City and Washington, carrying many of the world’s most powerful finance ministers, economic experts, lawyers and politicians north to the White Mountains.

At the opening of the conference, the main attraction seemed to have been Keynes himself. According to Lionel Robbins, he ‘was photographed from at least 50 angles … Lord Keynes standing up; Lord Keynes sitting down; Lord Keynes in plan; Lord Keynes in elevation; and so on and so forth.’ When the actual work began its pace was feverish (too much so for Keynes, who suffered a minor heart attack two weeks in). At the top of the agenda was the establishment of the two new international bodies. There was significant dissent from some of the non-Western countries about the way global hierarchies would be determined within the new system. The most controversial issue was the voting power each country would have at the IMF – crucial for determining who got to select its directors and perceived as a matter of prestige. Original transcripts of the conference’s proceedings show how passionately some of the poorer countries, such as China and India, fought to increase their representation. As one Indian delegate in the IMF Commission argued (ultimately unsuccessfully),

It is not merely the size of India; it is not merely the population of India – and I may say that one out of every four of the people represented at this conference is an Indian – it is that on purely objective economic criteria, India feels that she is an extremely important part of the world and will probably be an even more important part in the years to come.

Plans for international economic development were also controversial, as delegates from India and elsewhere fought for the IMF to commit itself to an ambitious postwar programme of development for ‘economically backward countries’. To little avail: these new institutions were designed with American and European interests in mind.

American dominance over the system was guaranteed by another crucial fact: in 1944, the US dollar was the only currency available widely enough to facilitate international exchange under the new ‘gold exchange standard’. This was intended to be a modified version of the gold standard which, in practice, would allow states to adjust their currency values against the dollar as they saw fit (depending on whether they prioritised economic growth, for example, or controlling inflation), with the value of the dollar convertible into gold at a fixed rate of $35 an ounce. What this meant was that, after the end of the war, the US dollar would effectively become the world’s currency of reserve – which it remains to this day (although it’s no longer pegged to gold). This arrangement would give the US the privilege of being indebted to the world ‘free of charge’, as Charles de Gaulle later put it, but would work only as long as the US saw maintaining gold convertibility as working in its national interest. Harry Dexter White apparently hadn’t envisaged a scenario in which it wouldn’t, but this eventually happened in the 1970s, when deficits from financing the Vietnam War piled so high that the US began to face a run on its gold reserves. In 1971, Richard Nixon removed the dollar’s peg to gold – effectively bringing Bretton Woods to an end – rather than raising interest rates to staunch the outflow of gold, which would probably have caused a recession (with an election on the horizon). Before this, the track record of the gold exchange standard had been pretty good: the years of its operation had seen stable exchange rates, unprecedented global economic growth, the rebirth of world trade and relatively low unemployment. This period also saw the emergence of many different models of the welfare state – in Europe, the United States and Japan – just as the economists behind Bretton Woods had intended.

What should we make of the fact that one of these economists was a Soviet mole? Along with his more famous colleagues Alger Hiss and Whittaker Chambers, White was responsible for passing sensitive American documents to the Soviets during the war, mostly concerning information he thought would help the Soviet Union secure a sizable postwar loan. White’s actions landed him before the House Un-American Activities Committee in 1948, but the extent of and reasons for his collaboration remain unclear. Most historical accounts see him as having played a relatively minor role, his activities driven less by ideology than by the desire to aid a wartime ally. If postwar peace depended on continued US-Soviet co-operation, the thinking went, it was better to keep the Soviets on side. Steil sees something more sinister at work, and much of his book dwells on White’s Soviet connections. He claims to have found new evidence linking White’s public activities on behalf of the American state with his private support for the Soviet Union: an undated and unpublished note from White’s papers at Princeton, in which he praised the Soviet model of socialist planning and suggested the US continue to pursue a strong military alliance with Stalin’s state. But the vague sympathy White expressed for Soviet planning was not uncommon among the American political elite during the 1930s and 1940s, before the orthodoxies of the Cold War hardened. And, as Steil himself admits, the actual plans White developed showed no influence of Soviet economic ideas, and his courting of the Soviets, who ultimately refused to sign up to the Bretton Woods system, ‘meant little in the end’. If that’s the case, why all the redbaiting?

Steil’s fixation on White’s Soviet sympathies is in keeping with the general tenor of the book and its focus on the conflictual origins of Bretton Woods. Steil makes it clear that he’s not a fan of Keynes and White’s creation, and seems to belong to what he refers to as the ‘small but passionate constituency’ that believes in a return ‘to some form of global gold standard’. Bretton Woods, on this view, was a foolhardy attempt to replace the strict rules of the deterritorialised and apolitical gold standard with a world economic system that relied on the discretion of national policy-makers. The state got involved where it had been rightly absent, and was given more sovereignty over national economic policy than it had ever had. Such nostalgia for the gold standard is a position outside the mainstream of contemporary economics, and tends to be found on the US libertarian right: Ron Paul made a return to the gold standard part of the platform of his 2008 and 2012 presidential runs. Steil cites the economists Hayek and Jacques Rueff as his authorities on the matter. What neoliberals like these two admired about the gold standard was the discipline it imposed on the state: following its rules promised to keep inflation and public debt in check, and to facilitate a nation’s integration into a global commercial system. But it did so at the cost of preventing the state from doing much at all in response to the economic distress of its citizens. As the great American Keynesian Alvin Hansen described life under this kind of arrangement, ‘If it gave us good times, we were thankful. If it gave us bad times, we accepted this as an inevitable concomitant of a system of free enterprise.’ When it failed to satisfy human needs, Hansen wrote, ‘we accepted the result with a stern, ascetic fatalism.’ The designers of Bretton Woods decided that the modern nation state could do better than this – and designed a system intended to buffer its citizens from the turbulence of world economic conditions.

Late 20th-century globalisation was set in motion just as the Keynesian consensus was falling apart. States were pressured to put on what Thomas Friedman has referred to as the ‘golden straitjacket’ of market friendly policies (one size fits all) to maintain national competitiveness in a liberalising world economy. Apologists for Keynes and White’s creation argue that a new Bretton Woods-style regulatory system could soften the sharper edges of globalisation in the interests of the state and national welfarism. Steil’s critique of the Bretton Woods system is intended, in part, to dampen their enthusiasm: there will always be an irreconcilable tension between national discretion over economic policy, he writes, and adherence to multinational rules. This is what doomed the Bretton Woods system and what will doom any successor. A durable system of international monetary co-operation, he argues, can’t exist without some form of a gold standard that prevents states from fiddling with their currencies. (He suggests that a digital analogue to gold could serve this function in the future.)

But Bretton Woods was also a system designed to guarantee that one power, the US, would have a disproportionate say in dictating the rules by which the postwar world economy would be managed. The American dollar was enthroned as the global currency of reserve, and the Bretton Woods institutions built in such a way as to ensure the US would have the greatest say in how they operated. Keynes was right in Savannah in 1946 to worry that these bodies would come to function less as internationalist institutions than as tools for ensuring US dominance. But things didn’t play out exactly as he’d envisaged. It was only after the end of the Bretton Woods system in the 1970s that the IMF and World Bank took on the roles for which they’d become infamous by the century’s end – as strict enforcers of the harsh rules of a liberalised international economy directed from Washington. From this point on, states in receipt of IMF assistance were pressured to follow a standard set of disciplinary and liberalising policy prescriptions: remove capital controls and tariffs, privatise, deregulate, break up unions and rein in public debt. Neoliberal orthodoxies replaced the statist and Keynesian ideas which had originally governed these institutions. In the 1980s and 1990s, the IMF became the handmaiden of the Washington Consensus, insisting that the world’s diverse national economies be reshaped according to its austere rules. This was not what Keynes and White had in mind.

Send Letters To:

The Editor

London Review of Books,

28 Little Russell Street

London, WC1A 2HN

letters@lrb.co.uk

Please include name, address, and a telephone number.